QT has drained ON RRPs to their normal level of near-zero, while QT hasn’t even touched reserve balances yet.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Balances at the Fed’s facility for Overnight Reverse Repurchase agreements (ON RRPs) have dropped below $80 billion for the second day in a row today, the lowest since April 2021, down from $2.4 trillion at the peak in December 2022, and well on their way to near-zero, where they were in normal times, and where the Fed wants them to be again as part of its QT, which by now has removed $2.15 trillion from the Fed’s balance sheet.

RRPs represent excess liquidity in the money markets that they don’t know what else to do with. This liquidity is outside the banking system. And it dropped by more ($2.3 trillion) than the liquidity removed via QT ($2.1 trillion).

To help ON RRPs get to near-zero, the Fed lowered its ON RRP offering rate – one of its five policy rates – at the December meeting by 5 basis points, in addition to the 25-basis-point cut on all its five policy rates. At 4.25%, the offering rate is now at the bottom of the Fed’s target range for the federal funds rate, as it had been before June 2021.

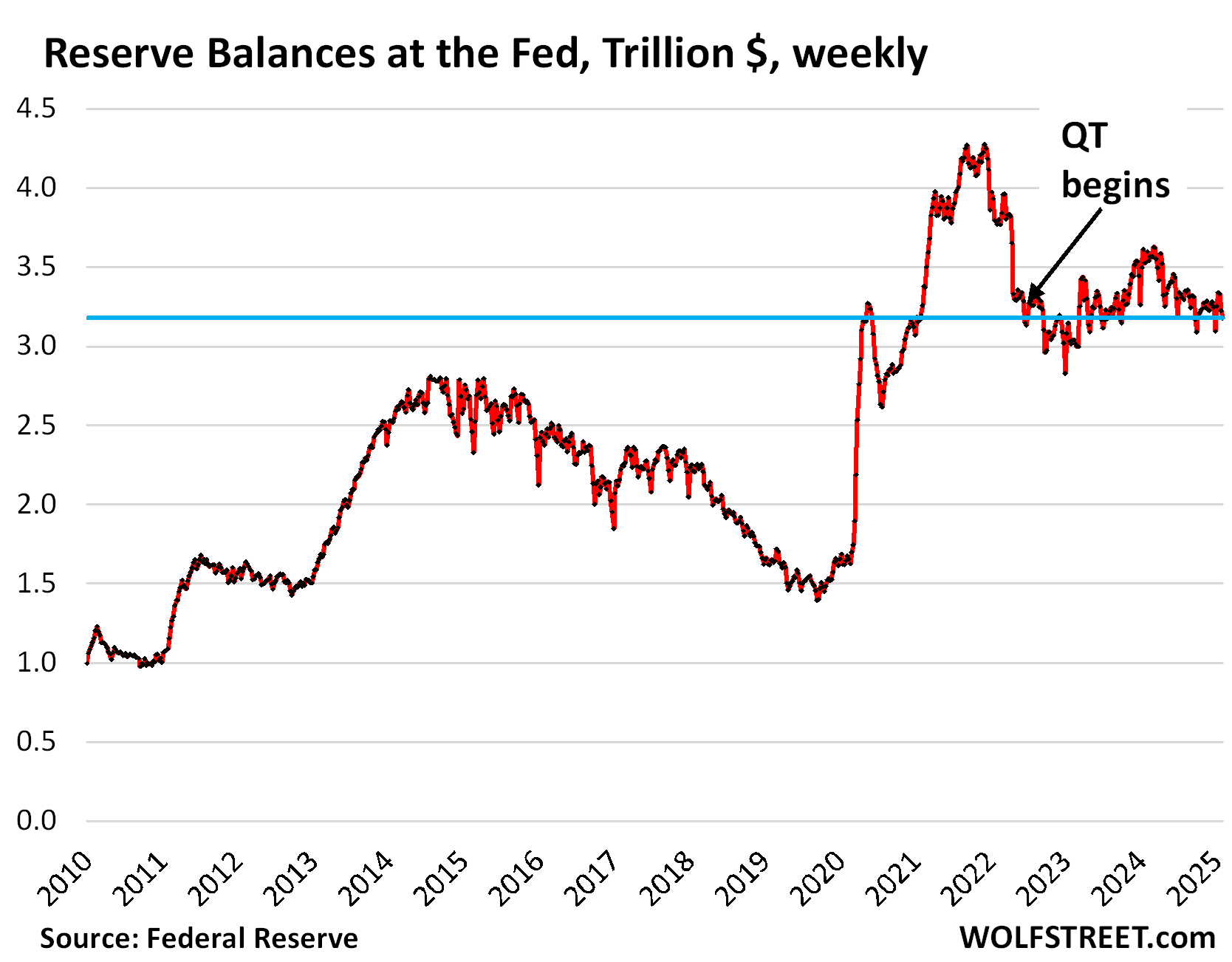

By contrast, reserve balances have not come down at all since QT started in July 2022. They’re now at $3.18 trillion, as of today’s balance sheet, about where they’d been in July 2022 when QT started, despite some ups and downs in between.

Yet bringing down reserve balances from the current “abundant” levels to merely “ample” (sufficient, adequate) levels is the primary purpose of QT. Reserves represent excess liquidity in the banking system that banks have deposited at the Fed.

All of the QT so far has come out of ON RRPs. But it’s reserve balances that indicate how much longer QT can continue – not ON RRPs. And as far as reserves are concerned, the impact of QT hasn’t even started yet:

The spike and its unwind in reserves started in January 2021, peaked in December 2021 at $4.25 trillion, and then liquidity shifted from banks to money markets, which caused reserves to plunge at the time and ON RRPs to balloon. But when QT started in July 2022, reserves were back at about $3.2 trillion and sort of stabilized at that level, while ON RRPs were being drawn down by QT.

Back in the day before QE, before 2008, reserve balances – then called “excess reserves” and “required reserves” – were small. Excess reserves were near-zero in the two decades before 2008, and required reserves, required by bank regulations, were between $38 billion and $60 billion in the two decades before 2008, just before QE kicked in.

Instead of piling up excess liquidity at the Fed, the banks satisfied their daily liquidity needs by borrowing from the Fed in overnight repo transactions at the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility (SRF) at the time. And that worked fine until QE messed up that system.

The Bernanke Fed, after it had started QE and reserves started piling up, killed the SRF because it was no longer needed.

Then in July 2021, in anticipation of QT drawing down the balance sheet, the Fed revived the SRF while no one was even paying attention because the Fed was still doing QE at the time. With the SRF, the Fed engages with approved counterparties (banks) in overnight repos. Banks can then lend those funds to the regular repo market if repo rates rise for some reason, and make money on the difference, which will keep repo rates from blowing out.

So in theory, the Fed now has the tools in place to shift from these huge piles of reserves on its balance sheet (and paying interest on them to the banks) to drawing down those reserves slowly but very substantially through ongoing QT and providing daily liquidity to banks as needed via its SRF (and charging interest on those repos).

When the repo market blew out in September 2019, the Fed did not have the SRF in place and was not prepared to deal with it, and was surprised by it. The revival of the SRF was a lesson learned from the repo market blowout. The mere presence of the SRF will prevent that sort of thing. And that, in theory, would allow the Fed to trim reserves slowly and over time by a lot more than Wall Street media outlet claim.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Wolf,

For all of us watching the ONRPP drain for the last couple years this feels like a noteworthy time we are approaching. Two follow-up questions if you have a moment:

1) Why are banks almost (entirely?) more hesitant to drawdown their reserves, than money markets take their money out of the ONRRP (other than the recent slight shift in rates)? Does this suggest that when it is the banks money going out the feds doors they will demand more (presumably interest)?

2). Is it it possible that with the SRF now back in place, we might be able to drain get all the way back to the old days of closer to mere required reserve levels?

I’m a novice on Fed plumbing, but I do run treasury for a small community bank. And for the last 4 years while the yield curve has been inverted banks have made more money on the reserves than they would get from buying treasuries and sometimes even normally higher yielding securities.

The last 2 months the yield curve finally normalized just barely and in preparation I’m keeping a lot less money on reserve at the Fed because the return isn’t as attractive anymore.

But I’m not sure that answers or even has anything to do with your question.

Thanks for the reply, and I appreciate the perspective from someone on the front lines at a bank. I can see the appeal of overnight rates, with the inverted yield curve. However, what I am struggling with a bit more is to understand why banks have been so much more hesitant to move money out of the Fed than the money markets. From my layman perspective, their motivation seem quite similar when faced with the same yield curve so I feel I must be missing some incentive or constraint that differentiates the two.

I believe money market funds generally keep a duration of not more than 60 days, meaning they are going to closely track overnight rates and a curve inversion won’t have as much impact on what they’re doing.

A bank’s securities portfolio is longer. A peer group of 250 institutions in my area has an average life of about 4.83 years (mine is 2.77.)

In other words, the bank is generally investing out on the part of the curve that is disadvantaged during an inversion. And when rates go up rapidly like they did in 22-23, there is no incentive to invest out the curve into an inversion unless you have a balance sheet that supports it.

Banks are always investing on some view of future interest rate movement because they are on that part of the curve. Money market funds are never doing that as they are in the very shortest part of the curve.

Honestly though, I have no idea how a money market fund works.

And I believe banks get about 15 bps more in interest than the ONRRP (maybe Wolf can correct me here if I’m wrong.)

Money markets need to keep durations short to meet liquidity needs. Rather than moving out on the curve to get more yield, they lend in private repo or just buy ultra short duration T-bills, both of which pay about 10bps more than the Fed’s RRP.

I appreciate the additional thoughts. Perhaps I am thinking about this all wrong but isn’t the shortest end of the curve overnight at the Fed? I would think if money market were focused on keeping money liquid they would want to keep as much as possible with the ONRPP, and it would be banks looking to withdraw their reserves and invest in the longer term. Yet, it seems the opposite is happening.

Yeah, CDs pay less on average and MMMFs are more liquid.

Click this link and take a look at the 3 yield curves.

https://www.ustreasuryyieldcurve.com/b/NmVfvN

The blue line shows you the curve on August 30 before the Fed started cutting. If you were running a money market fund and anticipated a Fed cut, you’d rather lock in a 60 day bill rate at 5.30 because 60 days later the RRP rate was 4.80 (the red line.)

When rates are falling like that there’s not a good reason to keep your money in RRP. You’re actually penalized by leaving it there. When rates are rising you have the opposite effect. You’re benefitting by sitting in RRP as you benefit immediately from the rate increase while your 60 day T-Bill retains the lower rate.

But if you’re a bank and you’re typically investing out at 2-3 years, there wasn’t really a good opportunity for you on the blue line or the red line. Maybe you would look to take money out of reserves and invest them longer on the curve when it somewhat normalized by 12/31/24 – the green curve. But probably only if you had a strong conviction that the Fed would keep cutting.

Once you get a normalized curve and you have 100bps difference between Fed Funds and the 5 year Treasury, banks will not have a reason to sit in reserve funds at the Fed.

Some banks will always carry reserves for liquidity though, at least at some level. It really just depends on the bank balance sheet.

BrianM

I’m not sure how money market funds run exactly but I can tell you that while the Fed is cutting rates, you’d rather be in a 30 or 60 day T-Bill than ORRP. That 30 day T-Bill gains in value when rates are cut against ORRP. You have the opposite effect on the way up, so you’d be penalized as the Fed raised rates.

But again, banks are generally further out the curve. And if you look at the yield curve from August, September and October it’s plain to see why you’d just sit in overnight funds. Now that the yield curve is basically flat, a bank might go out the curve a little if they anticipate further cuts. But you aren’t penalized much by waiting even now because the 5 year treasury has gone up 75 bps since the Fed started cutting rates and if that keeps up you can just leave your money in reserve funds until you get a price that pays you to move it.

Your #1. Banks are still awash in liquidity because QT hasn’t gone nearly far enough, so they have it, and they put it on deposit at the Fed to earn 4.4%. If QT runs for another $1 trillion from now, we should see reserves drop by $1 trillion, roughly. This also depends on the TGA (gov checking account at the Fed). Balances shift between the two.

Your #2. The banking system has gotten much bigger since then, along with the economy, so no, the banking system isn’t going to shrink, it will keep growing with the economy. But reserves can drop a lot more from here.

How far? One clue will be if the Fed in the future re-institutes required reserves. That would indicate that it wants overall reserves to drop low levels overall, but that each bank must keep a minimum of liquidity at the Fed.

One clue will be if the Fed in the future re-institutes required reserves. That would indicate that it wants overall reserves to drop a lot more, but that each bank must keep a minimum of liquidity at the Fed.

Wolf,

Thanks for the detailed reply. I think what I am struggling with is to understand the distinction between the money market folks and the banks in terms of keeping money at the Fed. It hasn’t been clear to me why the money market folks seems to be most willing to move out of the Fed over the last few years. One could argue the drawdown should be evenly split, given at one time they both had comparable sums at the Fed. It seems like the banks are waiting for some additional incentive (I assume rate premiums) that the money market have been willing to forego. Now that the ONRRP will soon be gone, I am wondering what will be that additional incentive needed to get the banks money out of reserves.

A bank needs to find a better investment than the overnight rate to invest in. During the inversion that comes in the form of commercial loans, which are usually priced at the short end of the curve. If you can find good loans, you make them.

But once the yield curve normalizes, securities and 1-4 family mortgages are also in the money and leaving money in overnight funds at the Fed is shorting the bank on returns they could otherwise get.

I’d be pleasantly shocked if the Fed manages to re-implement required reserves during this Presidential term, or at least the first two years.

I’m thinking that move would be viewed by the controlling party as “regulations = bad” and therefore a no-go.

I’d settle for doing $1T of QT at the current pace, then about $100-200B from the $1T, reintroduce required reserves paying 0% at a low reserve ratio that creeps up over time. We can call it “qualitative tightening” or something.

Well, maybe the Fed will stop losing as much money if they stop paying out on ONRRP, right?

They’re already losing less money. Their interest-costing balances are down by $2.1 trillion, and the rates they pay on those balances are down by 100 basis points.

if they don’t pay interest on it, anyone with that money will instead buy stuff with it and reduce yields elsewhere, while driving up assets.

That money gets loaned out in private repo instead of to the Fed. Repo markets are distinct from stock, bond etc. mkts.

Great article. Could reserves still go down to zero? think you have mentioned a 4 trill figure as base line in the past. Why is that?

They were never zero. Ever. There always were “required reserves,” required by banking regulations. But they were low.

And I’ll just repeat: The banking system has gotten much bigger since then, along with the economy, so no, the banking system isn’t going to shrink, it will keep growing with the economy. But reserves can drop a lot more from here.

Wolf,

Is it unrealistic to think reserves could go back down to $200-$300B (still more than 10x what they were for the most of the decades leading up to 2008)?

We aren’t supposed to post links, but surely this one is OK:

https://wolfstreet.com/2024/03/23/the-feds-liabilities-how-far-can-qt-go-whats-the-lowest-possible-level-of-the-balance-sheet-without-blowing-stuff-up/

I would be ecstatic beyond my wildest dreams if they go back to $1 trillion. That would be $2.3 trillion more QT spread over 5 years at the current pace. In June, we’ll complete 3 years of QT.

Yes, I suppose the real question is if the fed will hit a wall like the taper tantrum when they get below $2T now that the SRF is back.

Reserves seemed remarkably low and steady (fluctuating in the low double digit billions) in the decades leading up to 2008 (even with a growing economy) so I wonder if economic growth can really explain why $1T is now supposedly such a paltry sum?

The timing for when to wind down QT is completely subjective, wrapped around how they define “abundant” vs “ample”. The administration openly states their desire is to lower 10 year yields. One way to do that is stop QT. So, I expect QT to stop well before any rational person thinks it should. We will see.

Cookdoggie

“So, I expect QT to stop well before any rational person thinks it should.”

Since June 2022, people here have said the same thing… “three months from now, the Fed will be forced to stop QT and go back to QE because of yada-yada-yada.” And 2.5 years and $2.15 trillion of QT later, QT still going on, and has gone a lot further than any “rational person” thought.

They would stop QT if there is another shock to the financial system. That’s political pressure. Let’s hope that a shock doesn’t happen soon enough.

As noted by WR in this article and previously, the FED’s balance sheet has decreased from just a hair under $9 trillion to approximately $6.8 trillion today, representing a $2.2 trillion decrease which essentially has removed the excess liquidity from the RRP facility (which it should). I’m not sure if the RRP facility will ever get to zero again as some funds flow may remain to make sure the plumbing still works and for periodic balance sheet dressing but anything under $100 billion is basically the equivalent of zero from my perspective.

What’s interesting is that while the RRP facility has basically been drained and excess reserves remaining constant, the measurement of the M2 money supply (from FRED) has actually not changed by much at all since April of 2022 when it reached $21.7 trillion, decreased to $20.7 trillion in December of 2023 and has since increased back to $21.5 trillion by December of 2024. So effectively, no change in M2 even though the FED’s balance sheet has decreased by roughly 24%. I’m not sure how much longer this relationship can remain as if the FED’s QT efforts begin to impact bank excess reserves held with the FED, I would also anticipate M1 and M2 levels to contract as well. WR, would love your insight on this dynamic given your expertise/knowledge but at some point, if excess reserves begin to contract I would think there would be a direct correlation to the money supply.

I suspect these dynamics/trends also highlight the fact that excess funds/liquidity/reserves are still ample (as clearly noted by WR) which helps partially explain why inflation persists and that stock market valuations remain elevated. Translation, there’s still too much liquidity chasing asset valuations.

Another interesting observation is that the FED’s balance sheet was approximately $1 trillion in early 2008 and then jumped to approximately $4 trillion by the end of 2013, a 300% increase (primarily to address the LB/BS failures and economic meltdown during the Great Recession). Ok, steady as she goes with the balance sheet increasing to roughly $4.5 trillion by the end of 2017 which at this point, the FED began a QT effort which reduced its balance sheet to roughly $3.8 trillion by August of 2019 (a 15% decrease from its peak of $4.5 trillion). The importance of this date has been clearly documented by WR as in September of 2019, the repo rates blew out and the FED had to step in.

Then, welcome to Covid as the FED’s balance sheet increased from roughly $4.2 trillion in February of 2020 to just under $9 trillion by April of 2022. An incredible 800% increase in roughly 14 years, something I don’t believe has ever been close to being undertaken by the FED over the past 50 years. So does anyone wonder why inflation spiked as combining this type of monetary stimulus with disrupted supply chains and product/service availability presented the perfect inflation storm.

Now and one final observation, comparing the FED’s balance sheet growth to the annual growth of the USA’s GDP (nominal) from Q4 2007 to Q4 2024 (per FRED), it has increased in size from $14.7 trillion to $29.7 trillion, or roughly 100% over 17 years (representing an average annual growth rate of 4.22%). Yet, the FED’s balance sheet has increased from roughly $1 trillion in 2007 to today’s balance of $6.8 trillion, an increase of roughly 580% (representing an annual average increase of 11.9%). As you can see, the FED’s monetary policy has not been consistent with the GDP growth which indicates the FED now has a third mandate (beyond maintaining reasonable employment and inflation levels) which has been on full display over the past 15+/- years. That is, at all costs, don’t let the banking/credit/financial market system collapse.

To readers and followers of WR’s site, this is no surprise but unfortunately the FED seems to be caught in a new endless loop since 2007 as the bigger the crisis, the more monetary policy is used, which stabilizes the situation, but then seems to create another crisis/problem (e.g., excessive use of credit and leverage by businesses, overvalued equity markets, etc.), and so forth and so on. The real question is can the FED manage its QT policy to return its balance sheet to a reasonable level to support the economy and global monetary system (as remember, the global monetary system is tied at the hip to the USD and USTs), while balancing inflation and employment goals.

The great unknowns are just how much excess reserves and liquidity can the FED remove (and how quickly) to avoid another “financial accident” (which of course the FED is directly involved with). So far, the FED’s balance sheet reduction/QT efforts have been undertaken without many hiccups (although inflation remains above targets) but my thinking is that after it gets rid of the fat with RRP and begins to trim some muscle with excess reserves, we may see more impact on liquidity that spill over into other markets. Of course another financial accident seems to be just a matter of when (and not if) but for most of us on the outside, we need to express our thanks to WR for providing this invaluable information and perspective so that we’re better prepared next time around.

M2 is a screwed up measure and doesn’t include ON RRPs which is why the $2.2 trillion plunge in ON RRPs didn’t reduce M2. No one should look at M-2 as a measure of anything.

Hahahahahahahaha!!!!! Inflation forever!!!!! 2 million for a KitKat!!!!!

Good to see the Fed returning to its more traditional role of lender of last resort for banks, rather than the post-2008 trend of essentially being a market-maker for Treasuries.

“market-maker for Treasuries”

Nice one…although likely too mild. Mkt makers can’t counterfeit money under color of law.

The perpetual-fiscal-deficit-perpetual-Fed-buyer-backstop is inherently toxic long term.

After all, 50 years of running it has only greatly engorged the “necessity” of running it – that is the very definition of a counter-productive policy solution.

It’s been interesting seeing so many articles recently from Bloomberg, Wells Fargo, etc. saying the Fed will end QT by June because they can’t risk it going any longer than that.

Whether the flurry of articles are the latest marching orders from the ‘Illuminati’ or just Wall Street wish casting is likely correlated with the aluminum content of your head gear of choice.

They have been saying this for 18 months at least. A year ago, it was that ON RRPs couldn’t drop below $700 billion because of some kind of liquidity theory. And then it was something else later at $500 billion, etc. They will keep saying it.

And they also told us the economy would tank with rates over 4%, yet here we are.

Tightening deniers need to find a new tune to sing.

The empty RRP facility is no problem, because there is no correlation between RRP and banking reserves. Those who write the opposite are business reporters and traders who have no clue how the banking system works. Banking reserves are on a good level and indicate QT can continue on low speed.

And if liquidity is necesarily, th SRF will do the job.

@Wolf: It would be great when you can write a analysis about the Bank of Canada´s decision to end their QT, and begin a active balance sheet management. Many thanks.

I wrote about it in April last year when they first laid out this strategy. At the time, the end of QT fell into September 2025. What they did with their January announcement was move the end of QT up by a few months. Most everything else was kind of the same, including replacing GoC bonds as they mature with shorter term bills and repos.

https://wolfstreet.com/2024/04/07/bank-of-canada-balance-sheet-qt-sheds-64-of-pandemic-qe-assets-indicates-qt-might-end-in-september-2025/

Your first chart – ON RRP’s show a rapid drop starting in 2024. After the stock market covid recovery, the SP500 was almost flat from 22-24, and then it started rising in 2024. Is there any correlation to ON RRP’s going to near zero and the rapid rise of the SP500 starting in 2024?

Would the Fed’s continued QT keep upward pressure on rates? If so, what part(s) of the yield curve could be affected most, how far up could they go, and what timeframe could that happen?

Where is the MBS at? Any chance they’ll try to accelerate moving that off the books?