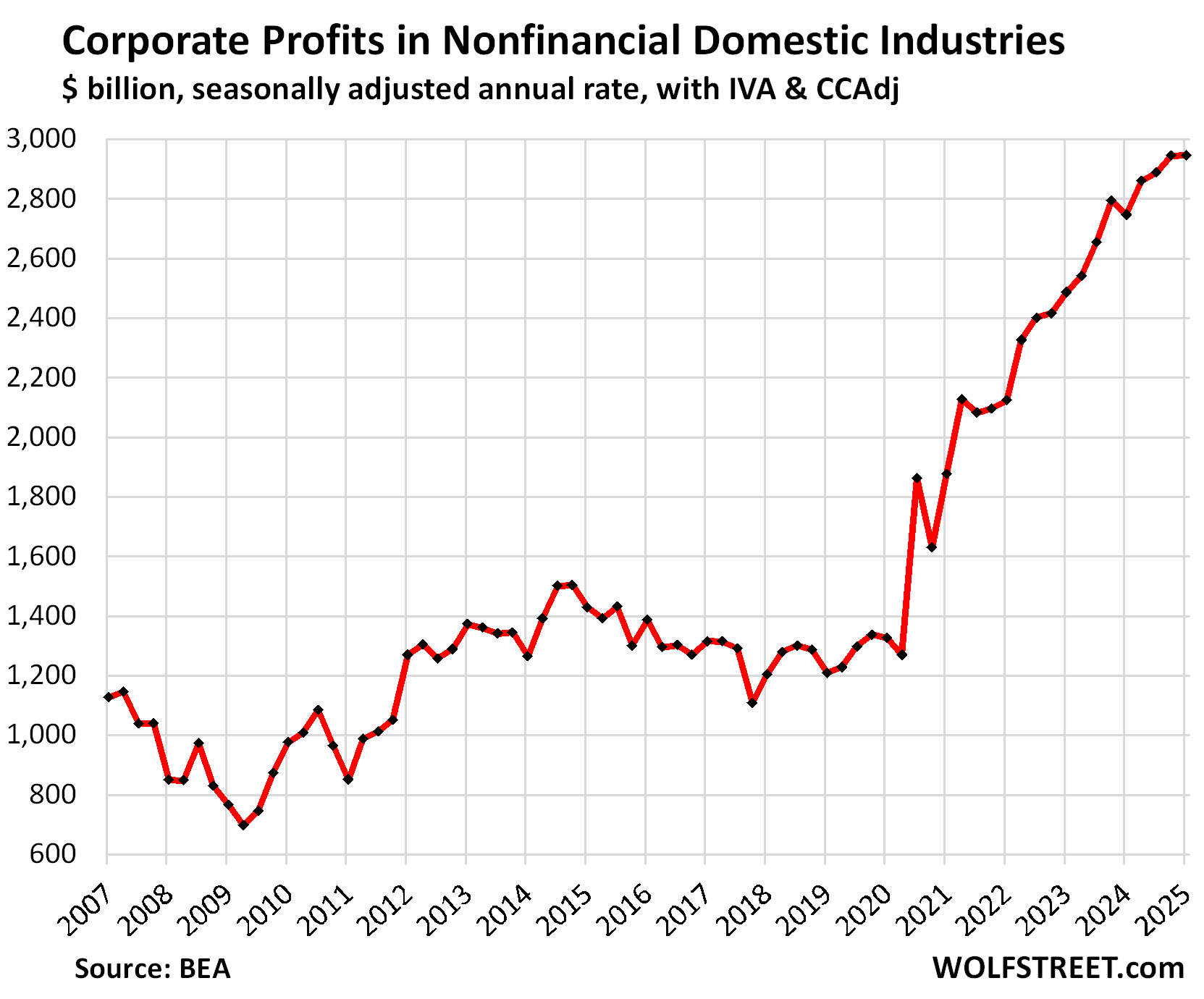

At this pace, tariffs will raise an additional $230 billion in corporate taxes a year. US nonfinancial corporate profits spiked to $3 trillion a year.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

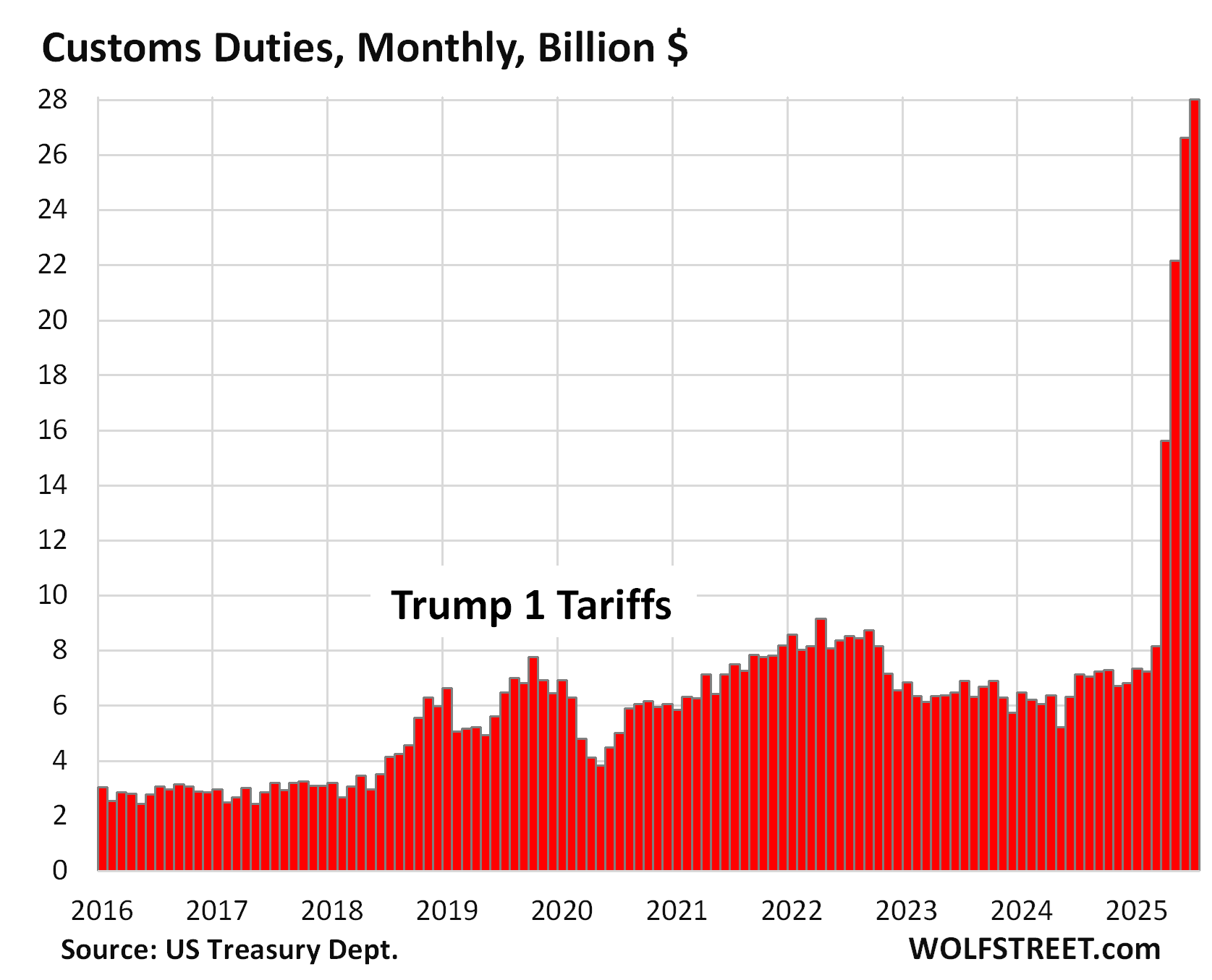

The amount in tariffs collected by the government in July rose to $28 billion, from $26.6 billion in June, $22.2 billion in May, $15.6 billion in April, and $8.2 billion in March, when collections from the new tariffs began.

In the three months from May through July, $77 billion in tariffs were collected. If collections continue at this pace, $308 billion in tariffs will be collected in the 12-month period.

In the fiscal year ended September 2024, the government collected $77 billion in tariffs. So the new tariffs would bring in an additional $230 billion in revenues.

That $230 billion in additional tax receipts may not sound like a lot within the fiscal fiasco that the US government has constructed.

But corporate income taxes collected in the last fiscal year fell to $366 billion (from $393 billion in the prior fiscal year). And this additional $230 billion from tariffs would raise the amount in taxes that companies pay by around 60%!

The tariff data is from the Monthly Treasury Statement (MTS), except for July, which is from the Daily Treasury Statement (DTS) for July 31, released on Friday. The DTS lists “customs duties” and “certain excise taxes” combined as one line item. The MTS – the July edition will be released on August 12 – separates “customs duties” from “excise taxes.” The difference between the DTS figure and the MTS figure reflects the excise taxes and has averaged $1.6 billion a month for the past 12 months. So the July figure here is the DTS amount of $29.6 billion minus $1.6 billion in estimated excise taxes.

Tariffs are taxes paid by businesses on goods that are imported, on their cost of the imported good. Whether or not businesses can pass them on to consumers to push up consumer price inflation in goods depends on market conditions – specifically on consumers.

If consumers refuse to pay whatever, if they shop around and compare, and buy from a competitor or forgo purchases whose price has jumped, then companies cannot pass on the tariffs because if they raise prices, their sales will fall, and they will lose market share.

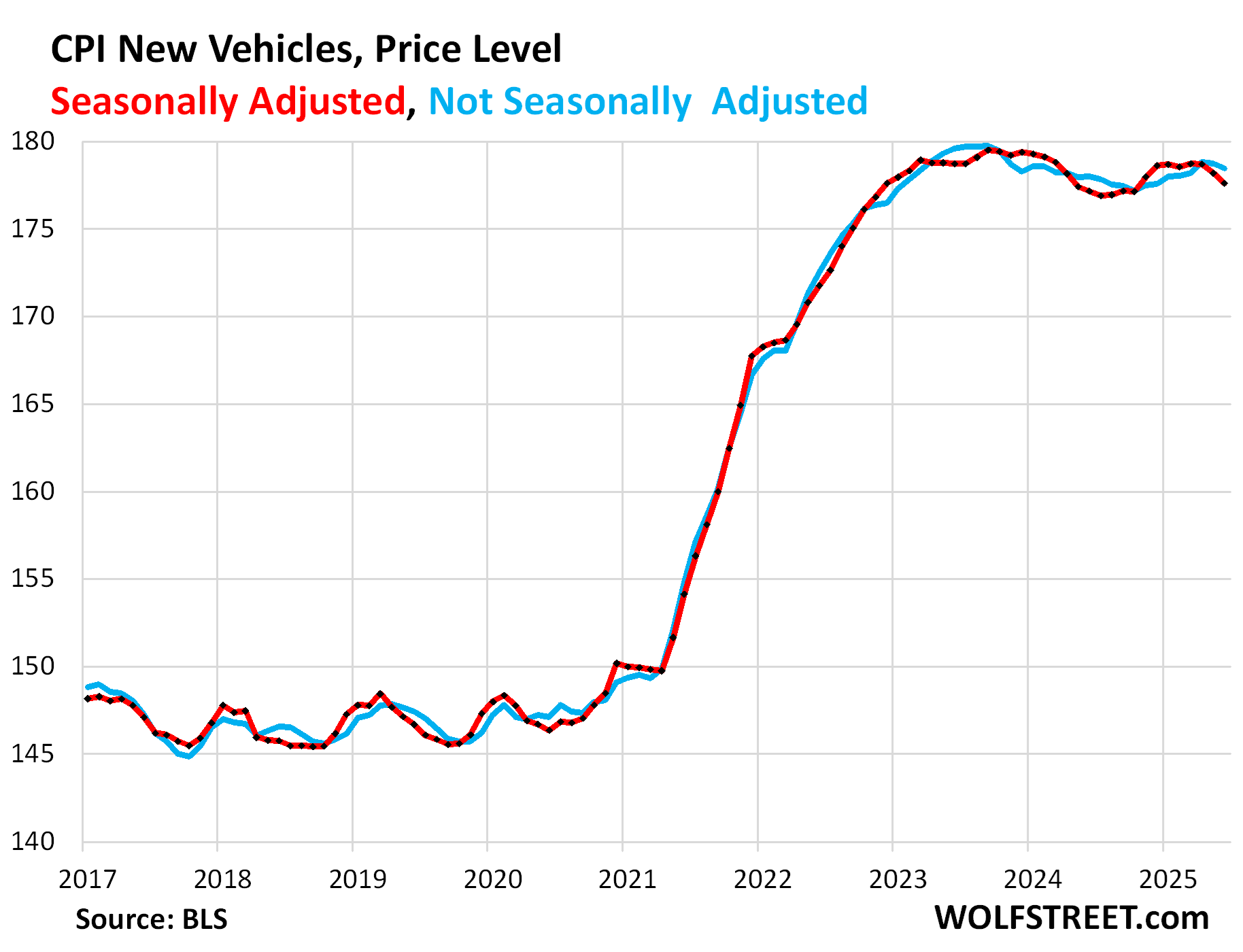

Which is what is currently happening in new vehicle sales. After automakers and dealers jacked up prices during the pandemic – the CPI for new vehicles soared by 21% in two years — prices hit a ceiling. It’s a tough market. New vehicles have become very expensive. There is not a lot of demand at these prices. Automakers and dealers have to offer deals to make sales. It’s a market-share battle.

Some models have 65% or 70% or more in US content, and have far less tariff exposure than imported vehicles with near-zero US content, or vehicles assembled in the USA with mostly imported parts that have little US content.

GM imports vehicles from Mexico, South Korea, China, and Canada after having globalized its production when it emerged from bankruptcy with the help of a government bailout. It said in its earnings warning that it expects tariffs to cost it $5 billion this year. But no biggie. It will continue to incinerate billions of dollars in cash on share buybacks.

Ford raised its estimate for its costs of the tariffs for this year to $2 billion. They have to compete with models from Tesla, Honda, Toyota, Hyundai-Kia, etc. that are assembled in the USA with much higher US content.

For automakers and dealers, the problem now is that consumers are no longer willing to pay whatever. The 21% price spike in 2021 and 2022, when automakers and dealers amassed big-fat record profits, was only possible because consumers, loaded with free money, were willing to pay whatever, including the odious addendum stickers that appeared at that time. But that was then, and this is now. The free money is gone, and consumers are no longer willing to pay whatever.

The Consumer Price Index for new vehicles for June declined for the third month in a row, seasonally adjusted (red line). Not seasonally adjusted, it eased for the second month in a row (blue line), and was about flat year-over-year. Here are the details of our CPI analysis.

Companies always try to raise prices and get the maximum price possible. They use “dynamic pricing” online where prices can change from minute to minute, based on various factors, including what is known about the buyer. They hike prices and then offer “discounts,” they’ll do anything they can to make comparison-shopping harder. There is nothing new about that, and tariffs won’t change it. Companies will always try to get the maximum price possible.

What keeps price increases limited, in normal times, are vigilant consumers that are not willing to pay whatever. That’s how a free market operates.

The free-money era of 2020-2022 destroyed that balance, and inflation and retailer profits – see charts further down – exploded.

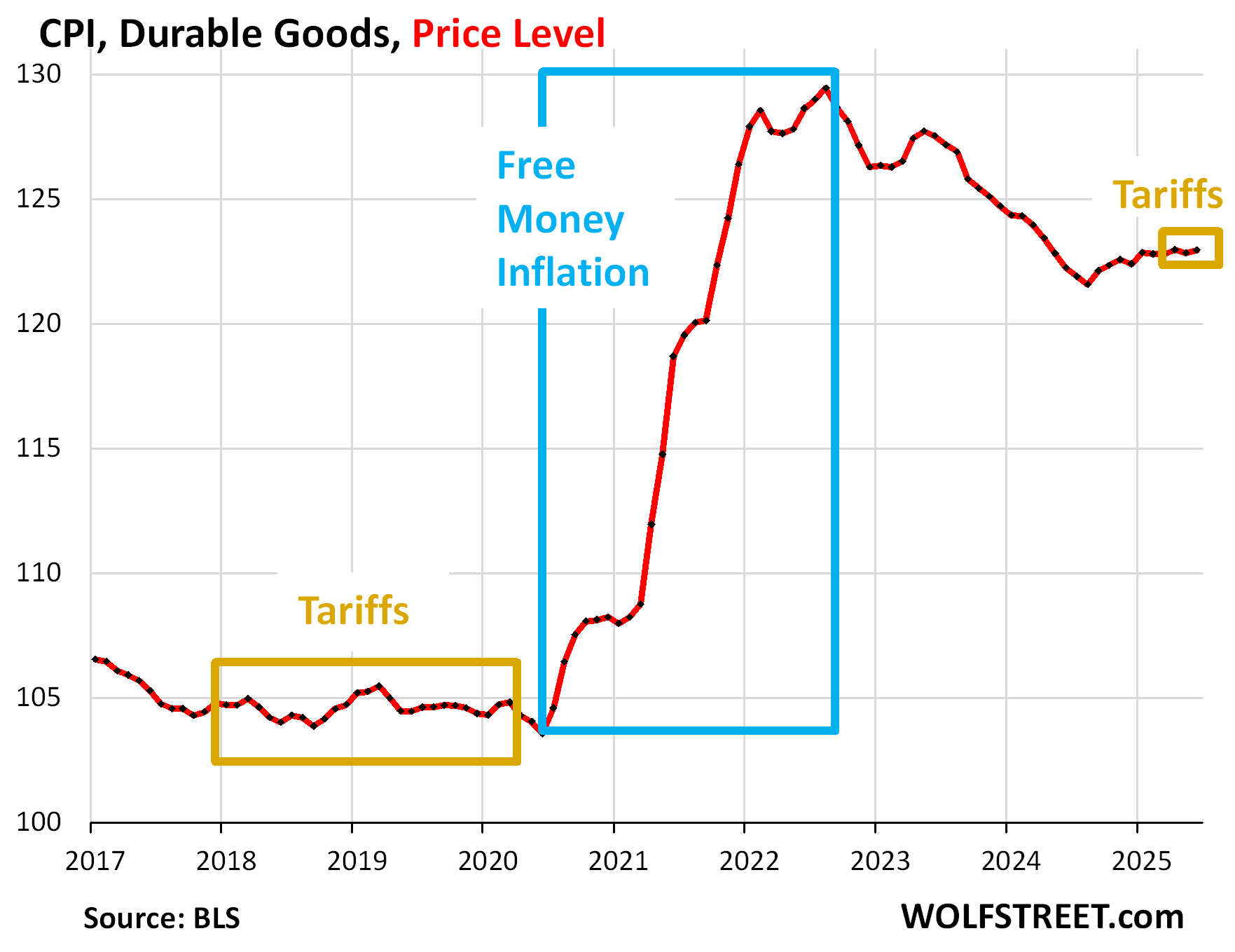

Durable goods prices overall barely budged in June from May, and year-over-year were up just 0.6%.

The durable goods CPI had exploded by 25% in two years from mid-2020 to mid-2022 during the free-money era. Then prices declined for two years (negative CPI). But from September 2024, prices inched up again through January, and since then have been roughly flat.

Apparel and footwear are also heavily exposed to tariffs. The CPI for apparel and footwear rose by 0.4% month-to-month in June but only undid the equal drop in May, with no price change over the two-month period. Year-over-year, the CPI for apparel and footwear declined by 0.5%. Consumers are in no mood to pay whatever.

Some prices of goods rose in recent months while others declined. Companies are always trying to raise prices. It’s up to the buyers to walk away. That’s part of a free market.

If a company’s sales crater and its market share shrinks because it raised prices and enough ticked-off consumers shifted purchases around, then that’s an expensive lesson.

So this is a very tough situation for companies to be in. To what extent tariffs can be passed on to consumers is unpredictable and depends on market conditions – on the consumers.

Corporate profits are an essential factor in the equation of tariffs.

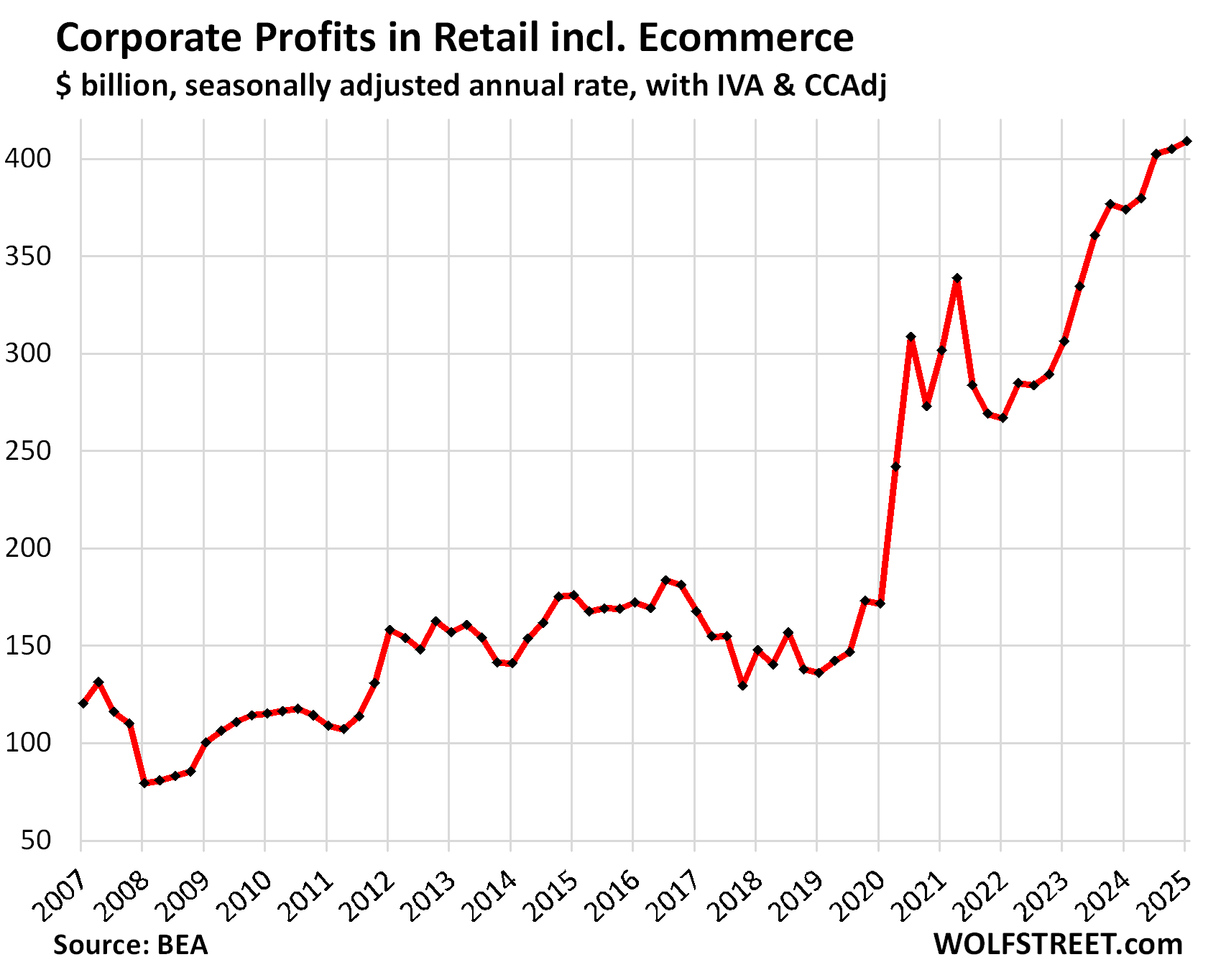

Pre-tax profits at ecommerce and brick-and-mortar retailers of all sizes exploded during the pandemic because consumers were willing to pay whatever, and retailers jacked up their prices by far more than their costs went up, and consumers paid those prices, and that’s where part of the inflation came from.

In Q1 2025, pre-tax profits at retailers were up by 138% from Q1 2020. Here is our discussion and charts of corporate profits by industry.

Pretax profits of all nonfinancial domestic industries rose to nearly $3 trillion annual rate in Q1 2025, up by 122% since Q1 2020. They include retailers, wholesalers, manufacturers, companies in information, companies in business, professional, and scientific services, etc.

The high-inflation era came from prices being jacked up, and profits exploded because companies raised prices far faster than their costs increased. Tariffs are now beginning to reverse some of those profits.

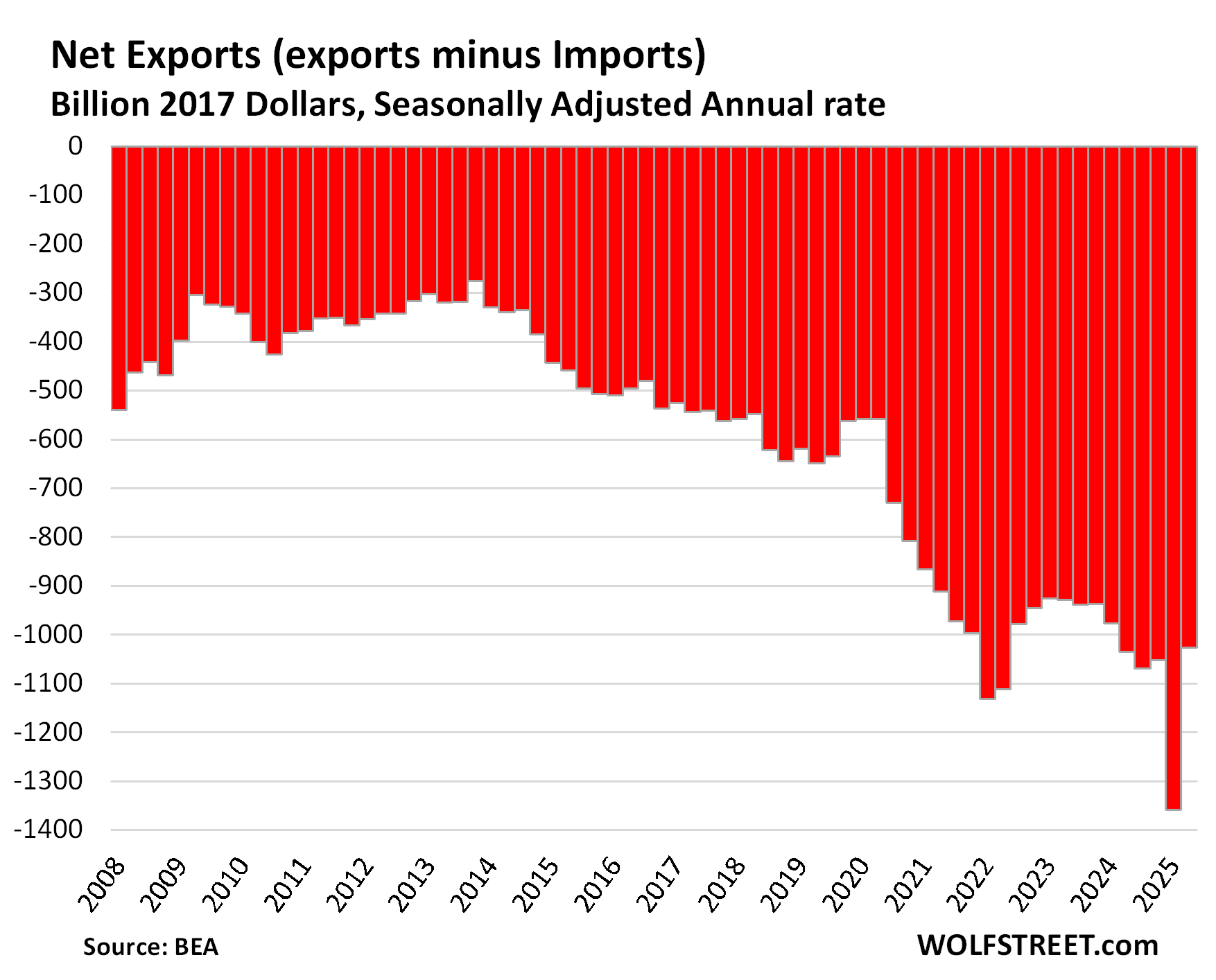

The primary goal of tariffs is to change the math in corporate investment decisions so that enough manufacturing gets developed in the US over the years to achieve a roughly balanced trade with the rest of the world.

Many big companies have already announced new manufacturing projects in the US. A factory construction boom took off in 2022, and over the past two years, spending on factory construction about tripled to a range of $18 billion to $20 billion a month, just for the buildings, not including the costs of the industrial robots and equipment that can dwarf the costs of the building.

These efforts take years, from initial decision to mass-production. Even shifting production to an existing plant in the US takes time.

So there is a long way to go before the trade deficit (negative net exports) in goods and services of over $1 trillion a year – the result of four decades of reckless globalization by Corporate America and government encouragement – turns into balanced trade.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Impact of auto tariff reductions to 15pc? Will that reduce tariff collection significantly?

What will reduce tariff collections significantly is more production in the US of autos and components. And that is the primary goal.

We should not reduce tariffs and target 20-25pc range. Not happy on 15 pc auto trace deals

We also need 10pc additional flat tax and 5 pc company tax on H1B and immigrant workers

two words: CORPORATE GREED!😡

Republicans refuse to use tariff income to reduce National Debt?

Money is fungible.

Even if they did apply tariffs directly to debt spending is still is more than revenue. So that’s a moot point for now.

What needs to happen is a freeze or a marginal cut in outlays (less than 5%) for a few years until economic growth can plug the gap.

The consumer is not only hit by tariffs but also by the 10% devaluation in the USD which adds another 10% to the price of imports.

I have a feeling fewer imports will be bought, meaning tariff income to the feds will be less, and whatever cost is absorbed by business will also reduce business taxes to the various governments (federal and state).

Nice experiment. Let’s see what the results are on inflation and the deficit in a year from now.

Companies pay little income taxes. Total corporate pretax profits were about $4 trillion in 2024, and they paid $366 billion in taxes in the US. So now you can add $230 billion to the taxes that companies pay in the US, and it’s still low.

The article discusses all this in detail.

I was afraid of the tariffs at first, but if they collect that corporate profit slush fund then President Trump’s policies truly are financial genius. Looking at the yearly tariff and corporate profit, there could be ten times the current tariffs and the companies would have plenty of money for a management reserve.

If only it were that simple, and stock prices weren’t based on corporate profits. Hope you don’t have a 401(k) that is heavy in equities!

If only corporations won’t pass on those costs increases to consumers and maintain their profit margins, but I’m doubtful they won’t do that. If corporations pay the bulk of the tariffs with their profits, I will be all for them. But history and economists say they pass on as much of that cost as possible. The author here doesn’t make a very good case as to why that won’t happen here as well, with their only focus being on cars maybe not being able to increase costs. There are plenty of other industries where all the players in the space will need/want to raise prices and the consumer will have no choice but to pay the difference.

Jim

Corporations got another HUGE tax cut in the OBBB, which changes the upfront tax deductions for investments, and research and development. For the big companies, the tax savings in the first year are in the billions of dollars. AT&T for example announced that it expects $1.5-2.0 billion in cash tax savings the first year. All companies that have investment and R&D expenses benefit from that. Amazon is a huge beneficiary of, with estimated cash tax savings of over $10 billion in the current fiscal year.

These tax cuts dwarf the tariffs.

So are companies going to pass on these tax cuts???? 🤣🤣🤣🤣

No, because corporate taxes (including tariffs) have zero to do with retail prices of goods. All taxes do is change the after-tax profits.

Retail prices of goods are set by what consumers are willing to pay, and not by what companies are wanting to get. If the price is too high, consumers don’t buy, and sales fall, and price cuts and discounts are next. That’s how retail works. Everyone knows that. Retail prices have zero to do with corporate taxes.

However, there is a lot of manipulative paid-for bullshit in the media from the WSJ and the NY Times on down, and in the social media – including lots of blocked commenters here — that tries to manipulate consumers into being WILLING to pay more. Commenters that participate in this form of consumer manipulation through bullshit are generally blocked here or get crushed manually.

So, the company that can provide a domestic product at a competitive price and profit does not have to fear the tariffs? It’s only a tax on those who are dependent on importing.

Such a domestic company would have to fear the tariffs being reduced or eliminated, because tariffs protect domestic producers from foreign competition. That’s why tariffs are a protectionist policy position.

Tariffs are also a tax on the consumer, who might prefer buying cheaper goods imported from places that have lower production costs than domestic producers. That’s the position of globalization advocates. Protecting producers from competition means less competition among producers, which is generally a loss for consumers.

For a given product, tariffs generally benefit domestic producers and hurt consumers and importers, assuming the good could be produced cheaper elsewhere.

However, anti-globalization (protectionism) advocates would probably argue that higher prices are worth paying because part of what you’re paying for is local economic production. Ironically, that has been an argument on the left and fringe left for decades, through ideas like buy local, small is beautiful, local currencies, the velocity of money, etc.

“Such a domestic company would have to fear the tariffs being reduced or eliminated, because tariffs protect domestic producers from foreign competition.”

This is somewhat offset by the initial capital costs (the building of the factory) being already paid. That’ll be part of the math in deciding whether to shift production or not.

If that was the case then nobody would have transferred their manufacturing overseas in the 1990s.

Having a factory already paid for doesn’t mean much when you can get your labor costs down by 60% – 80% and never having to deal with a union rep again.

Yes! That’s true! We’ve heard “buy local” so many times over the years. It’s basically saying, forego saving money on cheap foreign goods and support the business in your community that employs your neighbors and pays taxes. But ironically, the same people now scream about the tariffs.

Also, we need to remember that just as companies don’t always pass the tariff cost onto the consumer (like Wolf said), they didn’t always pass the savings of importing ultra cheap stuff to the consumer during the free-money Covid years. In other words, they raised prices before tariffs and weren’t trying to lower prices for consumers. Companies only look out for themselves.

I’d settle for American companies not based in Dublin, Grand Cayman, or some other BS. Or maybe Disney not whacking Americans (early) from training their foreign-born replacements for the same job a number of years back…

So, for me, while I don’t care either way about the tariffs nor the corporate profits, I get sick and tired of all these scammy practices going on that are just simple BS.

If the tariffs are the mechanisms that work to put an end to this crap, and happen to make companies that are doing an end-around on corporate taxes, actually pay up, then awesome. And no, I’m not a bleeding heart lib or socialist shmoe… Just an average Gen-X dude that’s calling some BS out. Like the article mentioned- if they have cash for share buybacks, then they have cash to burn… Or pay more in tariffs.

If they have cash for share buybacks, then why not increase Corp tax rates to at least 20% INSTEAD of using protective tariffs which could (& probably will) be passed on to consumers?

Christina, we could level a charge of 70% to 90% taxes on corporations, but unlike individuals, corporations are taxed on income that remains after deducting all allowable expenses from the gross income. That taxable amount will get much smaller

No. This is very simplistic and headlines-based view of economy.

1/ there are different kinds of tariffs, and different goal tariffs. Short term tariffs are heavy-handed and have little to do with economy — they are a political tool to force an opponent to implement certain policy you desire. Long term tariffs differ by goal: some are designed to simply avoid competition (bad), others — to level the playing field, yet others — force local production. Let’s talk the last two.

2/ Leveling the playing field. See, competition is never fare. Say, Canadian aluminum or lumber. Is Canadian lumber cheaper/more competitive because Canadians (fine people, btw) are simply better, smarter, more disciplined, etc — smarter competitors — than fat and lazy USers? Maybe. But also maybe because Canadian producer is pumped up by the Canadian socialist (more interventionist) government. In my mind, Canada to US is what Russia is to EU — raw materials and energy. These industries are known as “strategic industries” and government can’t let them fail (like US can’t let banks fail). So they have levers to pull (any, or all, or any combination): subsidized healthcare, low/free interest loans, softer taxation/environmental regimes, favored labor protection regulations, and so on. Now let me ask again — are you sure Canadian aluminum producers are more competitive, or simply more propped? The answer is — neither of us knows. But what we do know, is that mining aluminum builds infrastructure that can be shared to mine for rare earths. In fact, mining for rare earths on its own is prohibitively expensive, and there’s a reason why China owns pretty much all of it. Consumer will pay less short term, but inevitably pay more long term, once local competition is gone.

2/ Reshoring. Manufacturing is a backbone of any robust economy. Services are great, but the backbone is still production. There’s a reason why China manufacturing is ~40% of GDP and US is ~8%. Globalists said that US will design things and someone will produce or designs. As usual: “sounds great — doesn’t work”. Turns out, people who actually make things, are good at improving them, and are just as smart as US (of not smarter) to design more and better things. Net result — all of production and design moved there, and the best people in US can do — talk social issues, which does not help to fix bridges, etc. Things got so bad, that we couldn’t produce masks during pandemic — that’s an eye opener.

3/ Tariffs are tools. Wield them carefully — you are rebalancing economy and trade, fixing social and mental issues, etc. Misuse/overuse them — and suddenly everything looks like a nail — you hurt consumers and suffocate trade. Historically, greedy C suite was on zero-tariff policy (maximizes short term profit), so there’s little fear of overdoing tariffs (requires a lot of political will to resist C suite and globalists).

4/ Rebalancing trade and economy requires blanket tariffs. If you do targeted tariffs — corporations work around them: you tariff Mexico cars? Companies route Chinese cars through Canada or Belgium. They will assemble EVs where you want but the magic sauce (and all the complexity) is inside the battery pack, etc. Tariffs have to be full bore, across the entire economic perimeter.

My personal take — what happened is nothing short of amazing. Economically — I’m very excited for the next 4, but much better 8 or 12 years (will vote for the same economic policy).

Too Afraid Totell,

To me the idea that other countries are propping up their industries is mostly Western thinking. It isn’t that it isn’t happening, simply that those countries recognize either through ownership or support it is good for their society. I love to see countries that nationalize, much to Americas dislike and sometimes followed by coups or sanctions, as the collective value of things like mining and oil should be collectively owned and benefit society as a whole, not a few multinational corporations and their shareholders.

In short, there is nothing wrong with societies in investing collectively in itself, but the West seems to believe privatization is the only option. Finland is an example of a country that has struck a balance although backsliding in some areas now.

Dude: you don’t “mine” aluminum, you mine bauxite and it’s not a found mineral in Canada in enough quantities to mine commercially. Canada buys bauxite from several foreign entities.

So much for infrastructure building with aluminum. Bauxite and electricity (lots of it) make aluminum.

Canada has aluminum smelters that employ 30,000+ people in various provinces. The U.S. has four aluminum smelters in operation too.

Recycling is a very big deal for aluminum production, but why bother with details :D

As the arguments get politicized, I’ve noticed everyone’s brain turns off in order to try and make a point.

Well thought out analysis completely agree with you. We were sold a bill of goods on unfettered free trade to arbitrage labor rates. After 20 years and the emergence of a mercantile china we have lost the know how to manufacture and lost political control of our entire supply of goods. 30 years of policy doesn’t get reversed in 3 months, its a start and a good one.

Half the cost of making aluminum is the electricity.

Trivia re Aluminum: a common element in earth’s surface, altho rarely in percent economic enough to mine, it never occurs as the metal itself. You would never find a nugget of aluminum, or even as ore you could smelt out like copper.

The invention of the Hall process early in 20 th century. which passes bolts of electricity through bauxite made it available, and was one of the first uses of power from Niagara Falls.

If we had to give up either steel or aluminum, we’d have to think about it. No aluminum no jet airliners. When Henry Ford was approached by his engineers about building a metal airliner he thought they were crazy. But the Ford Tri-Motor was a success.

And you wouldn’t want a steel stepladder.

BTW: you aren’t allowed to use recycled AL for aircraft

Too Afraid Totell, I agree with most of your points. Where Canadian aluminum is concerned, my understanding is that the advantage is massive quantities of cheap hydroelectric power rather than “socialism”

Where the lumber is concerned I won’t pretend to understand it completely — it’s been an ongoing dispute my entire adult life, and the array of rulings and counterrulings at various dispute resolution mechanisms (WTO, NAFTA, other arbitrations) is frankly bewildering. Best that I can tell is way more of the land where logging takes place in Canada is owned by the government, which charges less in “stumpage fees” to logging operations than do the private owners of US land where logging occurs. Is this “socialism”? Maybe. Or maybe there’s just a metric fuckton more land up here?

Canada became a net IMPORTER of electricity from the US, importing more from the US than exporting to the US, starting in September 2023, and this continued through 2024. The grids in Canada and the US are connected, and they sell electricity to each other as needed.

The issue was/is BC’s hydropower, and the low water levels in the reservoirs.

The US has prodigious amounts of cheap energy, including natural gas (largest natural gas producer in the world) and is a major exporter. It’s just not cheap for households.

Buy local is a fringe left idea? What is wrong with you?

Reread my comment. It says “left and fringe left.” And saying buy local has been advocated by the left does not mean it has not also been advocated by those on the right. Rural areas where conservatives are overrepresented also have buy local movements.

But, sure, react with anger rather than thought.

Not so fast. We saw sometime completely different when Trump in his first term rsused the price on steel. Not only did the foreign manufactures charge the American consumer more due to the tarrifs but domestic manufactures seeing the opportunity to raise their prices as well due to the higher cost for imports. In addition the domestic manufactures still use imported parts in their finished goods thus we will pay more.

Find these price increases in 2018-2019 whereof you speak, relating to steel (which is WHY I posted these charts in the article so I don’t have to deal with this BS in the comments):

Is there any accountability mechanism for disclosing where the collected tariff money is being spent?

Better question:

Is there any accountability mechanism for disclosing where _all tax money_ is being spent?

The answer is “resounding no”. If there was accountability – a.i.d. staff would not be just fired, 99% of them would be jailed.

the billionaires got another tax cut

EVERYONE got a tax cut, if that’s what we are now calling “current taxes stayed the same”. The question is will we ever cut Federal spending.

Money is fungible. If you think the casino money is financing the school like they claim, then you are too gullible.

Where’s it being spent? Did you miss the big beautiful bill? This pays for a fraction of that. The government still has a massive deficit that is only increasing with that bill, it’s just falling into the widening black hole that is US debt.

The way the tariff rates bounce around on the whim of one DC Celebrity, there is no way of really figuring in advance what the tax being collected will amount to.

My guess is that tariffs are just a distraction.

My guess…you have TDS….lol…

Distraction from what exactly? Truly curious question.

A distraction from the fact that tariffs are a way for government to favor or disfavor any industry it wants. Those controlled by cronies will get breaks and the cronies will get rich by becoming oligarchs in charge of that favored industry.

Agree with you Nate, re: ”…cronies will get breaks and the cronies will get rich by becoming oligarchs in charge of that favored industry.”

And when you think about it enough, that’s exactly the way it has been forever and under every ”system” that has ever been.

Howsomeever, some might have optimism that with the continuing movement toward actual democracy and equality of opportunity, someday WE, in this case We the Workers who actually make stuff, will win, or at least break even…

God Bless and Good Luck to all who try, and especially those who get up in the morning and try to do their best!

That’s cute Nate. Did you think Cronyism only started when Trump got into the White house? If so every lobbyist before he took office did a masterful job of deceiving you.

The important fact to remember is this…

The money is going to the Government, and its coming from People and Businesses.

Good thing? It is a benefit to one side and a strain on the other.

So all the money the government has borrowed and spent so far. You don’t think ultimately has to come from people and businesses? Or as a deficit it just doesn’t count?

Sure it does…….and this scheme does the same. From the People to the Government. This isnt some new “magic”.

In the big game of government wack-a-mole, tariffs are a tiny income, while the big beautiful bill is a giant black hole of deficit spending. The first doesn’t begin to offset the second… but it keeps the press distracted. If the press were forced to allocate air time to % of government budget, tariffs would barely get a mention. Trump is breathing a sigh of relief that he can mislead the press so easily.

My understanding is that the tarriffs the US collects go into the TGA (Treasury General Account). The TGA is used to pay for US spending and has an accounting framework with specific categories i.e. Social Security, interest on debt etc. It has an accounting category called the general fund also. This is where the tarriffs flow.

I find it interesting the putative 3 trillion dollars in debt the CBO used for continuing the Trump tax cuts does not account for the roughly 3 trillion in tarrif collection over the same time period. At some level this gives me a glimmer of hope that we are not as screwed by the debt of this nation as I believed. Nonetheless the uniparty will sniff this out and will find some way to spend it.

Fundamentally Trump is raising taxes. Yes some will fall on corporations and be absorbed given the exorbitant profits they have enjoyed. But other will be absorbed by the consumer.

As a mechanism of raising revenue it is the least dirty shirt in the laundry in my opinion.

As always my conclusions welcome any feedback. This forum has some incredibly talented participants-hence I hesitate to even comment…especially when there is a Wolf lurking about.

Congress has the legal authority to set taxes and spending. As you point out, Trump is setting major taxes through tariffs. That power in the hands of a single man violates the Constitution and is thus worrisome.

I think that Congress granted the President that power through legislation. Of course, that legislation itself could be unconstitutional.

The legal mechanism is a bit different for the different types of tariffs, there’s Section 232 (and others) on specific goods, and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) for the reciprocal tariffs. The IEEPA tariffs are currently being challenged in appeals.

Like the Qatar plane using defense dollars to refurbish and then given to trump?

My understanding is that the tariffs are put in place to onshore domestic manufacturing. If this is effective, then tariff revenue will not stay elevated as you seem to suggest.

It will take quite a while for domestic industry to replace the tariffed imports.

Everyone says this. And it’s not wrong. But money talks. Watch how quickly things can happen once money gets involved. I think the world will be surprised at how quickly they can ‘adapt’

Now we just need to get millions of laborers who are willing to have the same standard of living as in India! Oh wait… we forgot about that part. The entire reason we off-shored manufacturing in the first place is that it was CHEAPER. We off-shored cheap jobs while protecting valuable high-end service jobs… and prices fell in many categories because of it (think tech, or appliances, or garments, or furniture). 25% tariffs aren’t going to change that.

Haha you don’t realize the difference between when the US was a manufacturing powerhouse vs now, do you? All the people complaining about not being able to afford college, healthcare, a home, a car. It’s a product of offshoring all your ‘cheap’ jobs. Why don’t we just offshore everything and we can all live in prosperity without having to work? Why keep any jobs here at all right?

Back in the day your ‘cheap’ job could support an entire family. Gee, I wonder why??

Blake: “All the people complaining about not being able to afford college, healthcare, a home, a car. It’s a product of offshoring all your ‘cheap’ jobs.”

Please explain. I could see college being overly expensive because of inflated demand due to everyone thinking that have to go instead of take blue collar jobs. Maybe you have a different explanation.

Healthcare to me is expensive because people are too fat and out of shape. There’s also bloated bureaucracy in there, and liabilities that force doctor’s to perform too many CMA procedures. And yes, greedy pharma companies subsidizing drug prices for the rest of the world.

Homes are expensive partially because due to costs and over regulation builders don’t build starter homes, just mcmansions and high end condos.

Cars are expensive because they push and we buy way more car/truck with way more features than we actually need.

These aren’t exhaustive explanations, but I’d be interested to hear yours to add to the list.

My explanation? When you shift your economy to be totally service driven most the money comes from within (finance/insurance/real estate/etc). Vs actual exports of products which bring real revenue and profits into the country. Relatively speaking, I think the US is living off its past success to some degree, which is ‘driving up’ costs of real things (healthcare, education, assets) because our standard of living is eroding somewhat, albeit very slowly. The standard of living a *blue collar or *unskilled worker could afford back in the 80s was a product of the country’s success globally at the time, is my opinion. Truly it’s much more complicated than this but simplistically I think that’s a big part of it.

Stephen Hren

That is the hope, and that would be a huge accomplishment, and it would massively boost tax receipts.

Manufacturing and its secondary and tertiary activities in the US generate a large amount in tax receipts at all levels of governments. It would be far greater than the tax receipts lost to shifting production to the US. Manufacturing and its secondary and tertiary activities have a massive impact on the economy, unlike services.

It seems like there are several generations here that have no idea about manufacturing because they have lost all contact with it?

…ah, the ‘unknown knowns’, the ‘unknown unknowns’, and an apparent need to frequently ‘reinvent the wheel’ (…occasionally-seen in ‘the study of history’…). Though the Great ‘Murican Consumer ‘is always right’, is it tough enough to doff its sailor’s cap and seriously-‘buyers strike’ to get its desired low-price stability while understanding it’s in competition with the concomitant reality of a greatly-increased world population and ITS improving living-standard cost-demands on the spacecraft’s ability to supply?…

may we all find a better day.

Hi Dustoff…..hope all is as well as can be expected…..completely get and agree with your viewpoint, as usual….although sailor’s cap didn’t connect, other than maybe gunboat diplomacy, which historically ALWAYS beats what most accounting books predict…the “West” is famous for it…The real world (the ball) of course has little to to with the books, although it is always a noble attempt to try to model society…..or any other phenomena our senses and memories deliver to us.

Did you see the guy who told me off-grid land was mere “peasant property”? I was proud of eliciting that….my comment WAS bait for a conspicuous consumer who doesn’t get the trouble he is in, as you mention. Doubt if it was a learning experience for anyone though….but I try.

Greetings, NBay. Becoming more-obscure than prior in the scratchings of my dotage (…and/or the effects of the pd on my cognitive switches), I fear. Anyhoo, the ‘cap’ was a nod to Wolf’s favored ‘drunken sailor’ ‘murican consumer-term (but now that you mention it, the ‘Big Stick’s always there, and oft-used, softly-spoken, or not…). Peasanting okay as possible out here above the tsunami line, not too-much wire strung as yet…hope the back is bearable-best!

“It seems like there are several generations here that have no idea about manufacturing because they have lost all contact with it?”

I find this statement quite true and seriously saddening to me. This country was built on manufacturing and I made my career out of it in heavy industry (metals). I finished in oil & gas production operations. My Dad and his siblings did the same.

Most young people I meet now haven’t got a clue how something is made and what raw materials and processes it takes to make that happen. NOT THE FOGGIEST IDEA!

Most of them can’t even open the hood on their car or change a tire!

But they do know how to use their iPhone and bitch about the U.S.

This country was built on natutal resourses. Manufacturing came much later and thrived due to zero protection for workers.

Manufacturing in the modern sense of mass production started with the steam age, same time as in Europe. Before the steam age, manufacturing was manual labor, as the word says. Some power was provided by draft animals and waterwheels, same here as in Europe.

But yes, the cheap-labor part was always important. It started with slavery. Which is why before the current administration, no US government ever really cracked down on illegal immigration — and some even encouraged it. It’s all about wage repression and cheap labor.

True. I recently saw a video of a guy desperately trying (and failing) to make a product completely in the USA. He had extreme trouble sourcing things like screws and other components, and he found that he could design a mould in CAD but then everyone wanted to outsource the diemaking. We’ve lost the ability to make our own tools.

Years of the Free Trade is Good Consensus will do that to people.

There was a reason why organized labor and domestic manufacturers freaked out over NAFTA and then let China into the WTO. They knew it would crush domestic manufacturing, and it did. This was a bipartisan effort, for the political scorekeepers.

Whether it was “good” for “the country” is a complicated question, often colored by personal interests. I would say it was roughly good for the college educated class (cheaper goods), and bad for the non-college educated class (lower wages). Geopolitically, it did not lead to a rise in democracy. Arguably, it did help out a lot of poorer nations, including China and Vietnam. Good?

But rather than go back to the 1960s, our trade policy is being rolled back to flirting with the 1800s, then settling around the 1940s-1950s, unilaterally, whimsimsically, and secretively. “Experts” are just guessing at this point.

Google will tell you Clinton was forced into signing the China Relations ACT by a Republican congress. But I remember he was a major proponent because he thought the US could help shape China. This was probably the biggest political and economic folly the US has made in the last 50 years.

Nate – good observations. Benefits of ‘Free(er) Trade’ was a cornerstone of Western post-WWII foreign policy, believing it would aid in warding off a repeat of that horror, especially in the face of the Soviet counter-examples in the following Cold War of global ideas and ‘wars of national liberation’. ‘Exceptionalism’ (especially in terms of offshoring U.S. industry), time, and lack of a coherent, bipartisan middle-endgame in its exercise (…not nearly-enough serious longer-term fp/trade reviews as outlined by Glen further down this comment trail) have contributed mightily to our current global situation…

may we all find a better day.

Thank you for posting thing. I guess you need to be old enough to have seen this as it was happening. Unskilled labor went to the parts of the world with the cheapest labor rates, while we protected (and emphasized) high-end, skilled jobs – in tech, pharma, software, defense, finance, etc. Even in manufacturing we kept the skilled positions, and off-shored / out-sourced the easy stuff that people could do without a high school education. It has certainly created a nation of “haves” and “have-nots”.

Greg P,

you have ZERO understanding of what modern manufacturing is. ZERO. You’re thinking of sweatshops. Got to a semiconductor plant, go to an auto assembly plant and get a clue.

Look up The Upswing by Robert Putnam. He shows just how many ways things today increasingly resemble the late 1800s. Written well before tariffs even. He doesn’t provide a satisfying solution, but the description is compelling. He puts us on a 120-year swing from individualism to collectivism, and then turning back toward individualism starting in the 1960s.

I don’t think the answer is rolling things back all the way to the early ’60s, but we’ve certainly overcorrected in many areas and are searching for balance. Reshoring very much included. Remember the ’60s also had way higher tax brackets, with the highest lowered from 91% down to 70% by JFK/LBJ.

Times change, and people don’t understand, China may have started out as a sweat shop, but only stupid people would believe that they are content to stay that way. Those factories are moving up the value chain, let’s take the iPhone for example, most of the manufacturing process there is automated on the subassemblies. It would be troublesome to shift it to the US because there is all the capital equipment someone has to buy. Then you’d have to train up the operators.

But, writ large, it is smarter for the US to bite the bullet and do it sooner rather than later. Simply because that way, China won’t have the geopolitical leverage of say stop ship on rare earth magnets and API for drugs.

It will take decades to get there, but the current admin has the right idea there even if the execution sucks. It has always been a merchantalist world, globalism was just an aberration to provide cover for a power that wanted to get to the top of that game.

Sendug – …Tuchman’s ‘The Proud Tower’ remains a good examination of the long tail of social conditions and movements arising out of the Gilded Age…

may we all find a better day.

I miss the days of USA manufacturing I am 68 a retried oilfield engineer . We wanted steel from USA only in the 80s and 90s because of quality then I moved overseas to work and the source did not matter . Eventually the international manufacturing took over almost all of the large international projects to the detriment of USA . Onshore and offshore .

I am thrilled we are making an effort to restore manufacturing in the USA terrific employment and the labor force had a great deal to look forward to each day. Each successful well I could generate in the USA provides a great deal of manufacturing and service jobs . Cheap energy for all and terrific jobs

If we get a domestic manufacturing renaissance, massive boost to tax receipts, but still have exploding national debt, is that a good outcome?

This is like asking: If I start exercising, but default on my mortgage payment, is that still a good outcome?

Your question implies that your solution to defaulting on the mortgage payment is to not start exercising. I give you a hint: exercising is good for your health, but it doesn’t impact the mortgage payment, and even lumping them together into one question is manipulative BS.

If 2017 is any indication when they last tried this with washers is that the jobs they create are ridiculously expensive, a study done by the university of chicago showed that.

It’s really all just bull$hit that is going to fail because it’s stupid engineering.

We all can go out and do stupid engineering, but why waste the time?

It’s above most people’s heads so they never understand the fake out.

Stupid ignorant bullshit and lies. Whirlpool manufactures appliances at several factories in the USA, including in my former hometown Tulsa. It manufactures washers in Ohio, and they’re competitively priced, and we have one, made in the USA, and it works great. Whirlpool sells those USA-made washers under various brands, including Whirlpool and Maytag.

You need to go somewhere else to spread these lies.

How wise is it to base economic policy on nostalgia? Jesus. I bought a speed queen on stupid talk like this and it’s been a did since day one, immediate trouble with broken control panel and parts and repairs are stupid difficult and expensive. There’s no magical talisman that makes us made stuff great. This is all so stupid.

I have a home-full of China-made junk, including a recently bought electric kettle — German brand made in China — that LEAKS since day one from the seam between the stainless-steel liner and the stainless-steel spout. The water runs down on the inside between the stainless-steel liner and the plastic outside shell and gets on the electrical base. Someone is going to get electrocuted from this thing. I posted an Amazon review about it.

…redolent of Deming’s principles (U.S.-grown, but initially-treated as ‘not invented here’ by the ‘Big 3’) being embraced by perceptive Japanese industry climbing out of the ashes of war, while the ones of Deming’s U.S. contemporary, ‘Madman Muntz’, were (and given Wolf’s example, still are. ‘Corner-cutting’ is a cardinal human trait that often gambles freely with its luck, another cardinal human trait, on its subsequent success) embraced by many industries in the PRC upon its re-entry of the world’s Capitalist economy…

may we all find a better day.

Did you read that University of Chicago study? Some other comment mentioned it a few months ago so I looked it up. As part of the calculations of the “cost” of the tariffs, the researchers included a rise in price of dryers which were not subject to the tariffs. It’s easy to conclude tariffs are very costly when you include price increases in a product that isn’t even subject to the tariffs. It occurred to me that since both washers and dryers went up in price by similar amounts, maybe the price increases weren’t related to the tariffs at all, but to some other factors. Of course, I’m sure that conclusion would have been anathema to the study’s authors.

1. the “Stupid ignorant bullshit and lies” referred to sufferinsucatash’s statement: “that the jobs they create are ridiculously expensive.”

and to sufferinsucatash’s statement: “It’s really all just bull$hit that is going to fail because it’s stupid engineering.”

The rest of his comment was just “stupid bullshit.”

2. What the study didn’t say is that people didn’t like those high prices and but bought from competitors, and sales of those high-priced washers and dryers fell, and then these high prices got rolled back quietly. End of story.

Wolf,

I was replying to sufferinsucatash about the study’s flaws from my point of view, I’m not sure if that was clear.

It was clear.

Please ignore — that was meant to be a reply to another post

I’m seeing the headlines about 50% coffee tariffs followed by photos and tweets implying that it will lead to a 50% increase in the cost of the coffee bought at Starbucks and similar places. Do people realize how little of the cost of those coffee-flavored beverages are attributed to coffee? The best article I could find says that between 3 and 4% of the company’s revenue is spent on beans. Even if that goes up by 50% for tariffs, that would still mean between 4.5 and 6%, which is an almost negligible part of your daily morning beverage. Something tells me that a 10% hike is more about padding the bottom line than Trump’s tariffs.

You’re right, poorly written articles. But the vast majority of coffee purchased is also not from Starbucks and is going to rise in price. I get mine in bulk from Costco, it’ll pretty much be a straight pass-through to me as a consumer.

Although saying that, it won’t be 50% in the longer run as they’ll just switch away from Brazilian vendors. More likely 15-25%. Still, I don’t usually like having to pay an extra 20% tax on goods I purchase.

Buy American coffee from Puerto Rico.

1. Coffee futures prices started spiking in 2021 and QUADROUPLED through January 2025. BEFORE TRAIFFS. Coffee prices have since the PLUNGED 33%.

People and media need to quit pushing ignorant bullshit about tariffs and coffee — or tariffs in general.

(BTW, Hawaiian coffee is awesome too. Coffee production has started in southern California).

https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/coffee

Do you actually think Puerto Rico can grow enough coffee to meet all of US demand? Puerto Rico grows 3 million pounds of coffee a year. A lot, but just shy of the 3.5 billion that the US consumers a year. You’re just about a 1000 times off, good job.

Really my assumption of 15-25% was assuming countries like Columbia and Nicaragua could absorb the impact, but that is already pretty optimistic.

@wolf. Lived in Hawaii for 20 years and still go back to visit family on the reg. Hawaiian coffee can be great if your taste buds love burnt dark roasted coffee. But it’s pretty expensive vs other names because you’re paying for the “Hawaii” part. Even more if it’s from Ka’u or Kona. There’s a reason people aren’t buying $50/coffee from there on the reg.

Taking about reshoring coffee production in usa and it’s territories kind of proves free trader’s arguments. Ideally, production of goods should happen in areas where there is a comparative advantage to do the economic activity.

Wolf makes a good point that a bigger influence on coffee prices is more likely to be climate change. Importers will work hard on playing the tariff game. If things get really bad, the tariff hawks will chicken out. Unwise to get between addicts and their fix. Especially as Brazil’s tariff rate is mostly to do some political adventuring.

Puerto Rico was the world’s 7th largest coffee producer.

Peaked out at 30M lbs/year.

Takes 4 years to get a mature coffee shrub though.

I’m just talking my book; the girlfriend’s father owns a nice little finca in PR. heh.

IMO: Starbucks and others are not coffee companies. They are milk and sugar companies with a hint of coffee.

How true! I ordered a back coffee last time I was in one and they kid behind the counter looked confused. Seems like that was not a menu item, and it was terrible coffee.

HA HA AA: I had the same exact experience the one and only time I had coffee at a star sucks, when I was stranded at an airport lounge overnight and they were the first to open at 0500…

After a sip, maybe 2 because of the situation, I threw it away, and just held out until another vendor opened in the other end of the airport an hour or so later,,,, and produced something drinkable…

Just unfollow those sources. Doing so doesn’t limit your exposure to news, only slop created to generate ad revenue or paint a terrible picture. On some cases raw ignorance but all those are best left to die on the vine if possible.

The amount of braindead BS in the media is astounding. Fire all these people that produce this stupid manipulative clickbait and replace them with AI. AI cannot do worse than that. But maybe they already got fired and this stuff is already generated by AI.

…but won’t THOSE ‘journalists’ simply join the corps already at the Fed???

may we all find a better day.

They could if they have a PhD in something or other….

Wolf, maybe you’ve already been replaced by AI and now AI Wolf is tricking us by worrying about AI. This is bad but can we even believe tariff dollars collected and jobs created? If we can’t trust the data all is lost!

In AI we trust.

“The primary goal of tariffs is to change the math in corporate investment decisions so that enough manufacturing gets developed in the US over the years to achieve a roughly balanced trade with the rest of the world.”

How do corporations get assurance that the tariffs will remain in place? I could build a doorknob factory in the U.S., hire and train workers, and start making doorknobs, because the price of foreign-made doorknobs has gone through the roof due to tariffs. But as soon as those tariffs are dropped, consumers will start buying foreign-made doorknobs again. So, I have to go to my shareholders and convince them that the U.S. government will keep the doorknob tariffs in place indefinitely, or at least long enough so that I can break even on my new doorknob factory? This seems like a hard sell, since if the tariffs can be applied by the wave of a wand (a “deal”) by the POTUS, they can be dropped just as easily. Do the tariffs consist of actual contractual trade agreements between countries that have some stability, or are they simply something that the POTUS could change overnight (since it seems that tariffs are ultimately determined by the POTUS alone)? If the latter, how can corporations make long-term decisions, based on what one person in the U.S. government decides autocratically?

There are many advantages to manufacturing in the US, including lead times, transportation costs, not losing your IP, avoiding supply chain risks (remember Covid?), etc.

The disadvantages are related to US taxes in that companies, when they produce something overseas, can route the invoices through a low-tax jurisdiction, such as Ireland, take their profits there, and then import the product to the US at a cost that generates nearly no profit in the US, and therefore no income taxes. The Senate did an investigation into Apple’s practices in 2013, and that’s exactly how Apple is doing it. Tariffs change that math.

Biden left most of Trump’s tariffs in place.

That said, not everything will be manufactured in the US, obviously. There will be trade for sure. The idea is to bring trade into balance, not to end trade.

Alternatively, companies simply transfer ownership of their IP to a foreign subsidiary. Items are manufactured in the US, shipped to US distributors, sold in the US – and the profits are routed by creative (and legal) accounting tricks to a low-tax foreign subsidiary as “license fees”. Look at the profits showing up on, say, Apple’s shareholder reports versus thise on it’s US tax returns.

There are already places where the US has a large surplus – such as BRAZIL – which is now faced with a 50% Trump Tariff.

Yeah…like making a better DEAL…..one done with extreme, genius, tons of past expertise, and incredible finesse.

You could easily write rally speeches…..that post had ALL the proper elements.

Too short, though. ;-)

There is also a huge disadvantage to manufacturing in the USA which is that it doesn’t and never will produce the goods that we want to buy such as BMW cars, Russian Chrome Diopside, Honduras Bananas, Columbian Mountain Grown Cofee, Daum Crystal, Baccarat Crystal, Bayel Crystal, and practically everything I do or would want to buy.

“will produce the goods that we want to buy such as BMW cars,”

LOL…

BMW SUVs, which are BMW’s most popular models and its bestsellers in the US, are made in the USA, in Spartanburg, South Carolina, BMW’s largest manufacturing plant in the world.

Most BMW “cars” sold in the US are made in Mexico.

BMW imports some low-volume high-end “cars” from Germany.

So the vast majority of the models sold in the US were made in the US or Mexico.

BMW has already said that it’s working on shifting more production to the US. That’s the purpose of tariffs.

Your whole comment shows that you microwaved your brain. NO ONE said that tariffs will stop trade or will stop imports. What kind of BS is this? There will be trade, exports and imports, but what tariffs will accomplish is that imports will decline, and production in the US will increase, and the gigantic fiasco trade deficit that you globalization-morons adore so much will shrink.

Just regarding one of your items dude:

After our two varieties of bananas starting fruiting regularly and I tasted them, I have not and will not eat ANY banana from anywhere out of USA…

Not ”exactly sure” why the HUGE delta in taste alone, but absolutely sure about the difference…

…sidebar VVNV-what varieties of banana are you growing down Flawda way? Recall an industry change some years ago indicating a blight in Central America was destroying the predominant strain we enjoyed as kids, forcing the plantations to shift to a more-resistant, but ultimately still-susceptible one (I noticed a change back then, as well)…

may we all find a better day.

BMW. If it’s unreliable and needs constant expensive maintenance, it’s junk.

S C B D,

I have a nine year-old M4 in the garage. Great car!

But better yet, I have my main stereo system centered around a pair of Magnepan 2.7 X loudspeakers that were made in White Bear Lake, Minnesota, on spec for me & finished one week after ordering them last December.

My preamp, amp, DAC and phono preamp are made by Schiit Audio in California and Texas. My subwoofers, with frequency-adjustable high-pass outputs to feed the amp and Maggies (set at 60 Hz), is from J L Audio; made in Florida.

As I listened to the Minnesota Orchestra’s live concert two evenings ago, starting with a new $350 Apple iPad (made in Vietnam) as the streaming source for the digital signal, everything after that was made in the USA. Why do I have a made in the USA stereo? Because it is the best sound for the money!

The concert finished with Dvořák’s 8th Symphony. It was composed in 1889 at Vysoká u Přibramě, Bohemia. The conductor was Akiko Fujimoto — who is female and from Japan. A dude from Bohemia and a woman from Japan. Yeah, I know . . .

I like my BMW motorcycle (which is 36 years old) but I would NEVER buy one of their cars.

The massive Spartanburg BMW plant in S Carolina(largest BMW plant in the world) imports the Austrian-made engines and drivetrains and assembles them into the X7, X5, X4, X3 and XM SUVs. X1 still made in Germany.

So, the critical component is not manufactured in the USA

They’re going to produce more of the components in the US. Already talking about it. That’s what tariffs are all about.

Bobber – to consider something I noticed many years ago in my late father’s experience with his humble, early ’70’s MBZ2(?2/3)0-his realization that it was the performed, required, ‘expensive constant maintenance’ that kept MBZ’s so ‘reliable’ per its contemporary rep. (Ultimately wound up with Toyotas over his following decades, also maintained by the book…).

Autos that seem to roll on with neglected recommended service, now THOSE are something!

may we all find a better day.

The CIT ruled that these tariffs are illegal. At oral argument, the Federal Circuit recently exhibited a fair amount of skepticism about their legality. I’m wondering if the Wolfosphere has an opinion on what’s likely to happen when the Supreme Court gets ahold of this issue.

IMO, extreme indeterminacy, sorry. The Court of Appeals is relying heavily on precedent, and this SCOTUS has shown a strong willingness lately to jettison that. Also last term it handed the presidency increased powers. The IEEPA legislation came from an era of the legislature seeking to contain presidential prerogatives. But the pendulum lately seems opposite, especially in SCOTUS. That could mean increased latitude for Trump to interpret what is an emergency, and to fashion a response. I think Roberts is very focused, however, on the scope of presidential power, and carefully walking along a line on that, one side and the other, so it should be a heavily reasoned opinion.

…hm. the general understanding and acceptance of the Eleventh Commandment is in obvious and admittedly-confused, retreat. It’s remaining corollary, the sanctity and application of Barnum’s Dictum (i.e.: “…never give a sucker an even break…”) now comes to the fore of the dealing art…

may we all find a better day.

Does the deficit in goods balance the surplus in services? Or is the net trade still negative? What are the risks of a country that loses it’s goods export market in the USA turning around and banning services imports from the USA? Like a boosted form of global digital tax?

This is the deficit in total trade. The goods deficit is much bigger. Services has a small surplus (a big part of services exports are foreign tourists spending in the US). So that chart shows the net of the goods deficit and services surplus.

For a detailed discussion of goods and services trade click on this link:

https://wolfstreet.com/2025/02/05/trade-deficit-in-goods-worsens-to-all-time-worst-in-2024-small-surplus-in-services-improves-overall-trade-deficit-worsens-by-17/

While too many variables will likely exist, a 5 years retrospective would be interesting on this. Did we achieve, or make progress, on the goals, and was this the right approach? As the global South grows in consumer power, albeit slowly, and as demographics take more hold here while also being 4.5% of global population. Reality is something needed to be tried but my sense is you can’t halt the overall global trajectory, especially while having inconsistent policies(increase revenues with tariffs, but massively spend more money with new legislation). Still not convinced that a lot of the investment promised with follow through as good publicity for them and to the administration. Yes, call me skeptical but see you in 2030 to discuss.

I know that you are like in your 70s and avowed socialist. I do not give two sh1ts about BRICS+ and their magical replacement of the USD. If you have lived this long, you should know by now that your failed beliefs of economic, social, and political equality sounds like the early stage of dementia.

Honestly, this is a site about making money, which I value Wolf’s perspective on things. In 5 years, I hope to God that I am at the my new beach house, smoking a big blunt, and cooking my red meat of choice on the grill. Our manufacturing base has increased by many fold. President Vance will continue the economic revival of our country. I want our country to succeed.

Did you see the news? EU, Japan, and South Korea just bent the knee. South Korea vows to help us rebuild our shipping industry which SK is a leader in ship building. EU and Japan will invest and purchase billions from our country. F@cking idiot Canada will bend the knee and come back to their senses. Monroe Doctrine will kick Brazil’s ass back into place. What are they thinking? They can shit in our backyard?

I know most folks do not want to admit it, but we are part of the US empire and we need to protect our interests to maintain of way of life.

Yeah, we have some big problems, but got to have some faith that we can come through this. Otherwise, you got somewhere else to go?

I have nowhere else to go, so I will make my stand here. Good luck.

Well, wrong on most accounts but you fit a lot of Issac Asimov quotes perfectly. Here’s to celebrating a country with unaffordable and uneven health care, expensive education and homelessness everywhere with continuing wealth inequality. Glad you got yours, the American way. Attacking people personally is always a solid intellectual path to constructive dialogue.

Clearly education is not on this individual’s radar. All that matters is one’s level of excessive wealth- that’s the American way, more important than ethics, decency, and compassion for fellow man.

Thanks for the reminder that people are happy to burn it all down just so they can rule over the ashes.

Why would any company think that tariffs are permanent? Trump is an old man with ratings falling.

His fault or not, tariffs will be blamed for inflation that is already baked in. Few will look deeper that the headlines and there goes the next election.

Most people are far more concerned with prices than where simething is made.

Most of his 2018 tariffs were kept by Biden until 2025 when Trump raised them.

The government’s appeal of a lower court order invalidating the majority of the tariffs did not go well this week in the Federal Circuit. Judges were very skeptical of the government’s position at oral argument.

Corporations that pay tariffs today likely will be getting a full refund within a year plus 6% interest. 7% for non-corporations…

From the commies at Tax Foundation:

“ Under all the imposed tariffs, the weighted average applied tariff rate on all imports would rise to 21.1 percent, and the average effective tariff rate, reflecting how much tariff revenue the new tariffs would raise after incorporating behavioral responses, would rise to 11.4 percent under the current tariffs—the highest average rate since 1943.”

Average tariff rate was 2% last year, apparently these tariffs can be ignored as nothing to see — and Santa will load up sleigh and ignore the spike in prices?

Tariffs are not “ignored.” They’re all over the earnings warnings by Corporate America that pays them, after hardly paying any income taxes on their $4 trillion in profits.

So yeah, companies have gotten huge tax cuts and loopholes over the years (by Trump too), and now they’re getting a little-bitty tax hike. Karma?

“If collections continue at this pace, $308 billion in tariffs will be collected in the 12-month period.” Excellent! At this pace we can pay down the national debt in 120 yrs! Just to give ya an idea bout how big our debt is…

the debt will never be repaid.

controlling/limiting the deficit to a percentage of the economy that causes it to shrink as a proportion to the economy is what’s important.

ryan

Why does this BS keep showing up here????

Because the number of people who understand public debt accounting approximates to zero.

The US fiscal deficit was about $1.3T through June 30. With three months to go in FY2025 it will probably come in around $1.7-1.8T.

FY 2026 is the first full year of Trump tariffs and permanent tax rates, so the question will really be if the cumulative deficit end up larger or smaller. Let’s say it’s $1.5, then $1.2 in 2027… Maybe it’s possible to actually balance the budget with increasing tariff revenue and increasing domestic tax collection as production and jobs are reshored. Keep the growth of the budget to a minimum and maybe we’ll get somewhere. That’s the hope anyway. Rates on US debt would plummet if there was actually a surplus as everyone scrambled to get the shrinking pool of “zero risk” debt. We’ll see.

“Keep the growth of the budget to a minimum” the decision was already made to do the opposite. The bill passed and the budget is ballooning and will continue to for many years. And that’s best case – no black swan, no additional excessive spending.

Here’s an article that states that Trump’s FY2026 budget request is basically flat from 2025 with some money shifting around. Not growing.

Social Security and Medicare are funded separately by payroll taxes and are not part of this discretionary spending budget.

https://usafacts.org/articles/whats-in-trumps-2026-proposed-budget/

Spending is half of it. Tax revenue is the other half, which is why the bill is projected to add $3.4t ($4t with interest) to the national debt over the next decade. But sure, if you ignore half of the equation, basically flat!

For Canada’s Carney, NO deal with USA might be better than bad one

Carney choose China. Trump is fine waiting to 2026 for the USMCA.

As I understand it, 2026 is the year USMCA is “reviewed” by the participants to see if they want to extend the deal past 2036, when it is due to expire.

Trump will be long gone by 2036.

Then go and read it.

USMCA IS TUMP. This was his carve out of NAFTA.

How hard can he push back? Read up on Article 36.6 of USMCA.

He will continue his push against China.

Started in his 1st term, And carried on with Biden.

I want my tariff rebate! But only for people like me. Screw the debt.

The boom in domestic factories can attributed to the Inflation Reduction bill that have tax benefits to promote domestic building. Tariffs weren’t in affect then and have nothing to do with it.

We haven’t even begun to see the affects of tariffs since menu don’t even hit into August 7.

25% inflation over this period explained a 200% increase in construction? Math-challenged?

Trump 1 tariffs on China were finalized in 2018, causing companies to start planning factories in the US. By the time they made the decisions and got planning and property purchases and negotiations with local authorities underway, Covid in March 2020 shut everything down.

Then as the economy reopened in 2021, those plans came back to life, now fortified by the fiasco to supply chains that the China shutdown was causing at the time, which motivated all kinds of companies. So this cause factory construction to take off in mid-2022.

Then Biden came along and started throwing out big incentive plans for factories in the US, $60 billion alone for semiconductors, which further ramped up the desire to manufacture in the US, even though the first actual cash wasn’t disbursed until late 2024.

Both Trump and Biden tried to get manufacturing revived in the US, both understood how important that was, and Biden kept most of Trump’s tariffs in place, but added the massively costly giveaways to the richest companies in the world. Trump is doing it by making these companies pay for not producing in the US (the much better option). But both methods work toward the same goal.

Mr. Richter,

“GM imports vehicles from Mexico, South Korea, China, and Canada after having globalized its production when it emerged from bankruptcy with the help of a government bailout. It said in its earnings warning that it expects tariffs to cost it $5 billion this year. But no biggie. It will continue to incinerate billions of dollars in cash on share buybacks.“

This is a bit off topic. You frequently (and rightly so) lambast corporate share repurchases. Share repurchases are, in my mind, a tool and all tools can be used both correctly and incorrectly.

My question is when, if ever, are you in favor of a company repurchasing their shares? If so, any chance you’d share your thoughts on the subject?

Either way, thanks much for your work and have a great day!

Kile: Although clearly not the Wolf who knows more and shares more of his knowledge, I will reply with a bit of mine.

Share buy backs are a good thing when ALL the shareholders are clearly aware of the entire situation of the company.

Otherwise, as is almost always the case, when the company C-suite folx are doing share buy backs to enrich themselves, it is almost always a ”rip off” of the other shareholders.

While this is usually kept quiet or entirely out of sight of the majority of shareholders in order not to spike the price of the shares, that too is almost always to the detriment of the majority…

Just one reason I got OUT of the SMs in the 1980s after 30+ years before this kind of manipulation began.

Good Luck and God Bless,

Look up rule 10b-18, which should allay your concerns.

Kile,

“when, if ever, are you in favor of a company repurchasing their shares?”

I’m less critical of share repurchases when the company has no debt, generates a huge amount in cash, is investing some of that cash, and doesn’t know what else to do with the rest of the cash, and ends up using a portion of that leftover cash to buy back its own shares. But even then, they should increase their dividend payments, which go directly to shareholders, instead of blowing this cash on share buybacks.

There are not many companies like that. And GM certainly isn’t, it’s borrowing money to buy back its own shares.

I agree, and just about the only one I know that meet those criteria is Apple.

Even there, the fact that they have no idea what to do with their money besides buybacks is not a great look. In such a rapidly changing field like tech, if you’re not investing every dime into staying ahead of the curve you’re at risk of being wiped out.

So I would add an additional criteria: where the company is in a mature industry without a huge need for further investments and product development.

I would say Microsoft rather than Apple. Apple has taken on $100 billion in debt since it started its share buybacks

https://wolfstreet.com/2024/10/28/boeing-launches-22-billion-share-offering-to-get-some-breathing-room-dodge-junk-credit-rating-after-having-wasted-64-billion-on-share-buybacks/

Is this the first stage of implementing VAT?

No, but Europe’s VAT system does kind of the same thing as tariffs, but it’s far broader

Doesn’t VAT also apply to domestic produced goods? I always thought of it more as a national sales tax, whereas tariffs are specifically targeted at imports.

Yes, like I said, it’s broader. But a Vat us not a sales tax because it works differently. The tax is added at each stage on the value that the stage added, hence the name. For example, if my business is in a country with 20% VAT, and I buy wood, glue, and screws to make a table, I pay 20% VAT the amount of (my sales price of the table minus my cost of the wood, glue, and screws). The retailer that buys this table from me pays 20% VAT on (their sales price minus what they paid me). So the VAT gets added in phases as the product goes through the pipeline.

So when Ford wants to import a Mustang to this country (it does), right off the bat it pays 20% VAT on its wholesale price to the dealer. The dealer then pays the VAT on the difference to retail price. Then there are tariffs on top of that, plus “malus” in France for example, and some other stuff depending on country.

Obviously unknown at this point but firing somebody with no evidence based on numbers that look bad is a slippery slope. Without evidence this suggests that numbers could be fabricated(or formulas changed to produce positive results) in the future in labor and other areas and many in the world, including this website, trust those numbers. If economic numbers become untrustworthy that can impact trust in investment here and of course opens the door potentially for other countries. Of course, he might just get rid of a Biden appointee and put in an objective person but that hardly has been the approach thus far as mostly just loyalists. Statistics aren’t perfect but that is very different than inventing fictitious numbers for political or personal reasons.

Related to this article, no reason to not trust tariff numbers but the door is open and does anyone think it couldn’t happen?

…sounds like Lysenko is rising from the dead…

may we all find a better day.

Trump is a bully and a chaos agent and has no impulse control. I don’t see how this firing helps anyone.

We’re now in the first stage of the transition to George Orwell 1984. It’s very bizarre. So many things in that novel are happening right now. Of course Trump wants to control the statistics. Almost better than controlling the Fed.

https://www.bea.gov/data/intl-trade-investment/direct-investment-country-and-industry

If the tariffs are free floating, should there be movement in FDI to support them?

If you look at the totals, you’ll see that the cumulative US investment abroad was $6.83 trillion, v. cumulative FDI in the US of $5.71 trillion.

In other words, the US invested $1.1 trillion more abroad than foreign entities invested in the US. The US should invest more in the US, and we’re seeing some of that.

As an antidotal semi-off topic, to the booming tariff narrative — I live not to far from a popular brew pub.

Throughout the year, I’ve noticed a large decrease in customers, based on my window view of an outdoor patio.

Last summer, almost every night had tables of drunk slobs, having fun until midnight.

This year, Saturday and Sunday breakfast lunch crowd almost extinct — and zero late night parties — the tables that do sit people, are vacated after maybe two hrs or less.

Parking lot used to be far busier and the drifting smell of food is far less noticeable as I go for walks.

This pub has several locations and has been a stable well thought of place for years.

Out of curiosity, I just pulled up a story from march about one of their pubs closing:

“The financial challenges have become too burdensome to continue the business, as food costs continue to rise and consumer dining and drinking habits change”

Very much a micro observation, but I attribute the decline in consumers, to high cost of living:

NACHOS / $16 Extra $5 for meat

It was $7 for a pint a year ago, and the current price seems top secret

That’s probably somewhat normal in many places — just as home prices, insurance, groceries, clothing, cars and whatever else you need — and in general, this is before tariff costs get managed, by either businesses or consumers. The end of year holiday season will be impacted by higher cost pressures.

In a deleted post, I suggested we’ll see far more shrinkflation — as businesses substitute smaller portions, alongside higher prices.

That incoming price shock is the price people will associate with these tariff revenue spikes. Nobody wins in this deal.

1. I don’t understand why you post this thing in an article on tariffs. Neither the nachos nor the beer brewed at the brew pub are imported, and are not tariffed. If the price increases, it’s because of regular inflation.

2. Alcohol consumption is falling sharply in the US (as well as in other countries, such as Germany). Older people have figured it out, and many younger people never really got going. They’re into cannabis. In addition, total US beer sales have been declining for years because people switched to wine and other stuff. Per-capita beer consumption has collapsed over the past two decades. Over the past two years, even wine consumption has plunged, leading to the bankruptcies or closures of numerous wineries, one of which (with a publicly traded stock) we covered here. This is a big problem here in Wine Country. But it has zero to do with the economy or tariffs; it’s a result of health concerns about alcohol. All the boomers I know have cut back on alcohol consumption, and by a lot, including me.

3. A brew pub is like any restaurant or bar out there. If they don’t have the right magic, they will die. Our favorite restaurants are hard to get into. The dying ones are nearly empty. That’s how it goes. Lots of brew pubs and craft brewers go out of business all the time, and that has been going on for years.

Wolf, Redundant, brings up a point I encounter every morning during my cursory search for believable information. I believe you are correct on the description and action of tariffs. However I can’t count the number of comments I’ve seen saying the coming inflation will be caused by tariffs.

I also happen to live in a small village having a local bar & grill with a similar problem as costs go up.

Question is “How does the current administration explain their forward plan to the general public?” In an understandable way. Not an easy answer is possible.

A bit of politics I plead guilty, sorry.

It’s the Fed’s job to get inflation under control and keep it under control. If this kind of normal inflation on stuff like US-made beer and nachos in restaurants (services) and in other services begins to re-surge, and overall inflation rates get hot, the Fed needs to re-hike its rates. There really isn’t a whole lot to explain to the public.