That scenario is re-emerging as a real possibility in recent economic data.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

When the Fed cut its policy rates on September 18, it looked at labor market data showing a sudden slowdown of job creation to weak levels, and it looked at decent consumer spending data, so-so income growth, and a very thin and plunging savings rate. And the trends looked lousy.

But starting 11 days after the Fed’s decision, the revisions and new data arrived. And the whole scenario changed.

So at a summary level, economic growth in three of the past four quarters, as revised, was substantially above the 10-year average of about 2.0% GDP growth adjusted for inflation:

- Q3 2023: +4.4%

- Q4 2023: +3.2%

- Q1 2024: +1.6%

- Q2 2024: +3.0%

The third quarter looks pretty good too: The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate for Q3 real GDP growth is currently 3.2%, of which consumer spending contributes 2.2 percentage points, and nonresidential fixed investment contributes 0.9 percentage points.

In terms of the hurricanes and tornados that have caused a lot of destruction and horror: Because worksites were closed temporarily, and people had trouble getting to work, there will be a temporary spike in weekly unemployment claims and an uptick in unemployment in the affected regions. But the US has been through the horrors of hurricanes and tornadoes many times. What follows quickly thereafter is the spending and investment boom from clean-up, replacement, and rebuilding, which are all contributors to employment and economic activity.

A bunch of massive up-revisions after the Fed meeting.

Consumer income, the savings rate, spending, GNI, and GDP were revised up on September 27, so 11 days after the Fed’s rate-cut meeting.

The annual revisions of consumer income and the savings rate were huge this time, going back through 2022, and consumer spending was also revised up, but not as much.

These massive up-revisions of income and the savings rate resolved a mystery: Why consumers have held up so well. And they brought growth of GDP and GNI (Gross National Income) back in line by revising GDP growth up some and GNI growth up a lot.

The magnitude of the revisions was astonishing, and we speculated here the large-scale influx of legal and illegal migrants – estimated by the Congressional Budget Office at around 6 million total in 2022 and 2023, plus more in 2024 – was finally getting picked up in some of the data. A big part of them have joined the labor force, and many of them are working and making money, and spending money, thereby increasing the income and spending data.

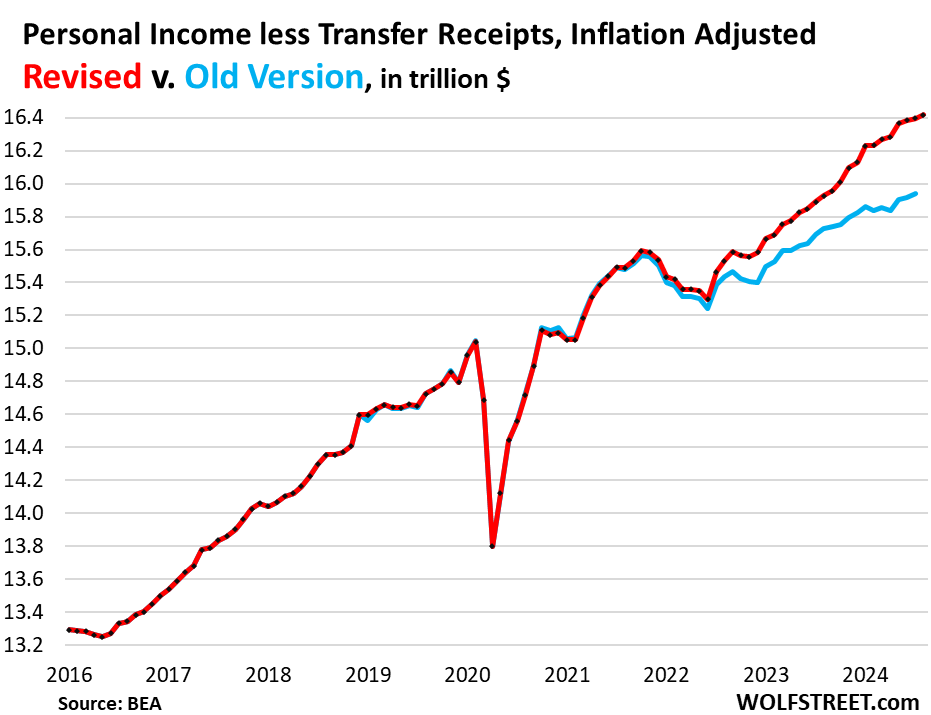

Between July 2022 and July 2024, over these two years, personal income without transfer receipts (so without payments from the government to individuals, such as Social Security, VA benefits, unemployment insurance compensation, welfare, etc.) adjusted for inflation:

The revisions to the savings rate are important because they showed that consumers spent substantially less than they made going back through 2022, and saved the rest, which bodes well for future consumption.

Income was revised up massively, and spending was revised up but less, and so the savings rate – the percentage of the disposable income that consumers didn’t spend – was revised up in a stunning manner: The revised savings rate for July was 4.9%. The old version of the savings rate for July was just 2.9%.

We have seen in the ballooning cash accounts, such as CDs, money market funds, and T-bills, that households are not only flush with cash but kept adding to their cash holdings, and we used this continued ballooning of cash holdings as a better signal of the health of consumers than the anemic savings rate. Now the massive revisions of the savings rate going back two years confirmed this.

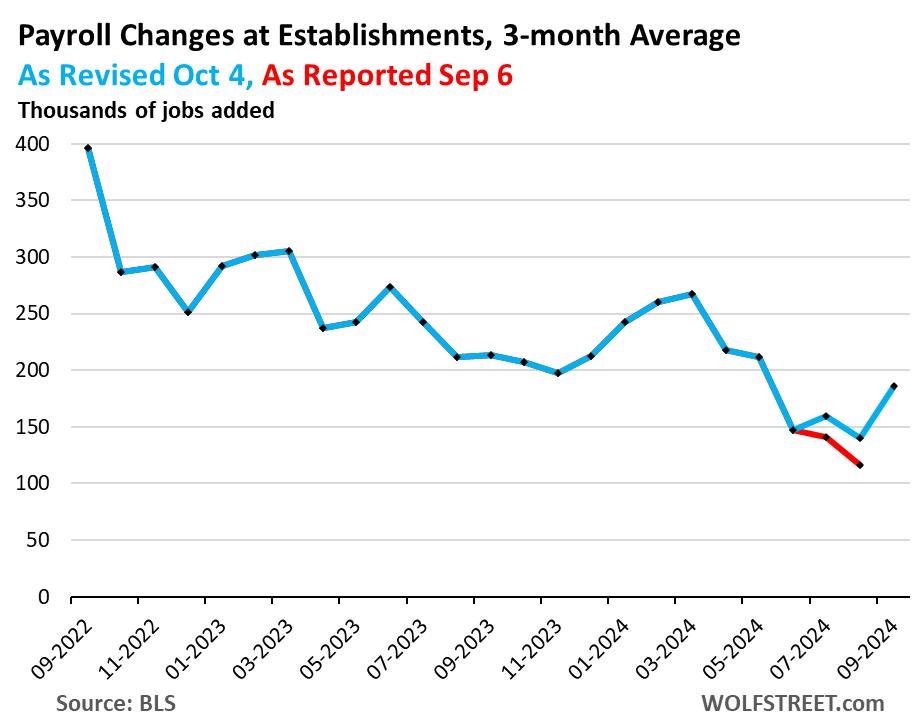

The nonfarm payroll data was revised up on October 4, so 16 days after the Fed meeting.

The primary reason cited by the Fed for the 50-basis-point cut was the sudden deterioration of the nonfarm payroll data: The three-month average of payroll jobs created had slowed dramatically in July and August in part due to downward revisions of prior data, and we pointed that out at the time, it was a disconcerting sight.

But with the strong September jobs report came the up-revisions of prior data that prompted this headline here: OK, Forget it, False Alarm, Labor Market Is Fine, Bad Stuff Last Month Was Revised Away, Wages Jumped. No More Rate Cuts Needed?

“Pandemic distortions and millions of migrants suddenly entering the labor market, who are hard to track, have wreaked havoc on data accuracy,” we said in the subtitle. There is nothing like data whiplash.

It also solved another mystery: The weak payrolls data for July and August didn’t match other employment data, which had been fairly good.

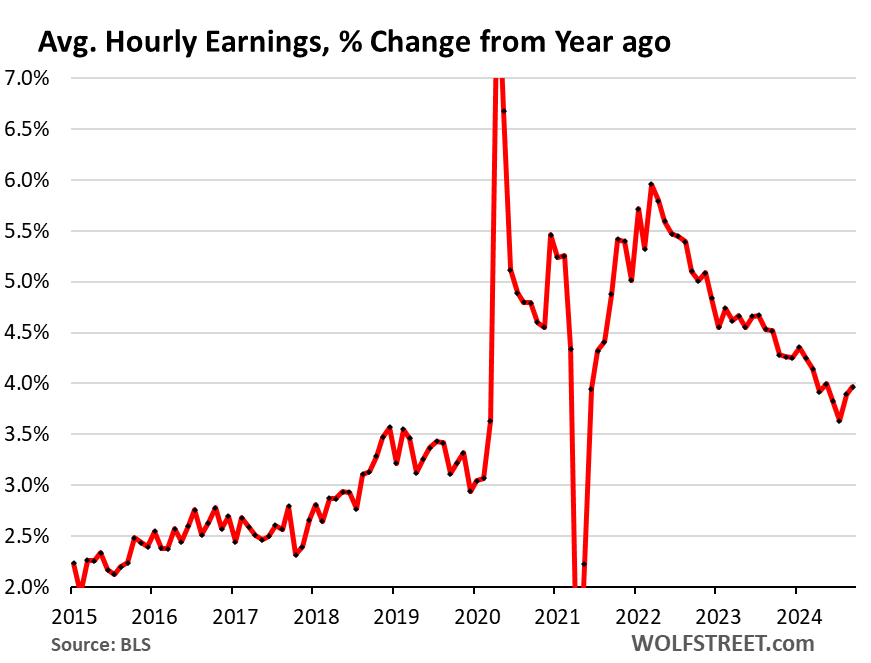

The increases in hourly earnings were also revised higher, with the revised three-month average income growth rising to 4.3% annualized.

The year-over-year increase rose to 4.0% for September, the second month in a row of year-over-year increases. Those two months combined increased the most for any two-month period since March 2022, and are well above the peaks of the 2017-2019 period.

“So in terms of inflation – and what the Fed has been worrying about – this accelerating wage growth is not going in the right direction anymore,” we said at the time.

And so inflation is no longer going in the right direction.

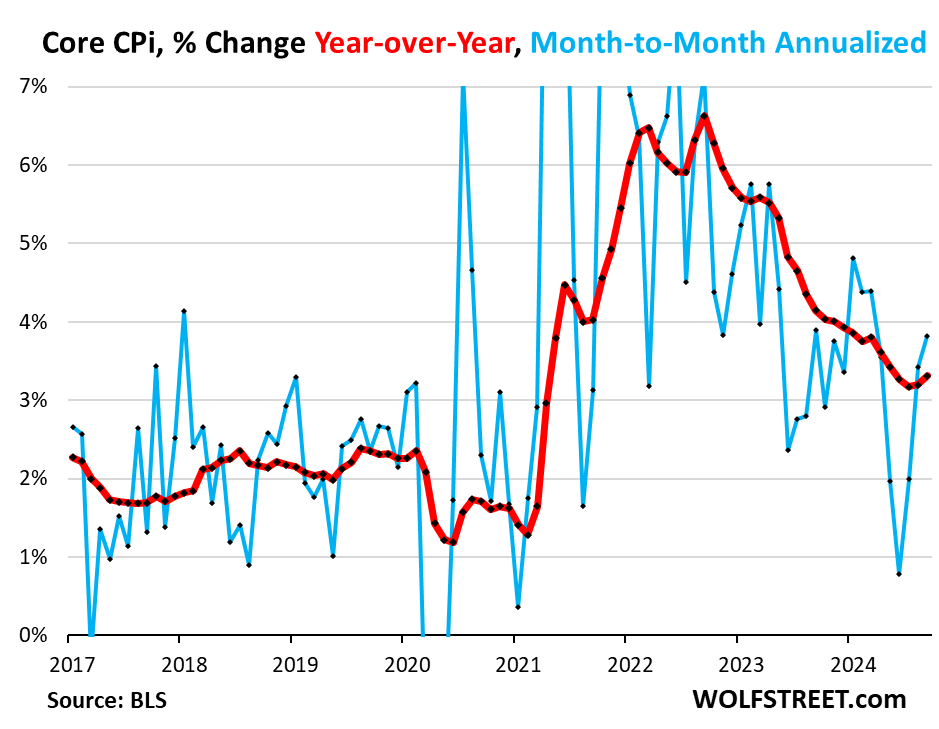

Energy prices have plunged, and that has papered over the problems beyond energy.

Core CPI, which excludes energy products and services and also food, accelerated for the third month in a row in September to +3.8% annualized (blue line), which caused the 12-month rate to accelerate to 3.3% (red line).

Inflation in services has turned out to be sticky. And then there are motor vehicles, where prices had been falling – plunging for used vehicles – which had been a big factor in pushing down core CPI since mid-2022. But they U-turned in September and headed higher (for details, see our “Beneath the Skin of CPI Inflation”).

This is not red-hot inflation like it was two years ago, it’s a lot lower than that, and the Fed has succeeded in bringing inflation down, but it’s re-accelerating inflation that’s still too high to begin with.

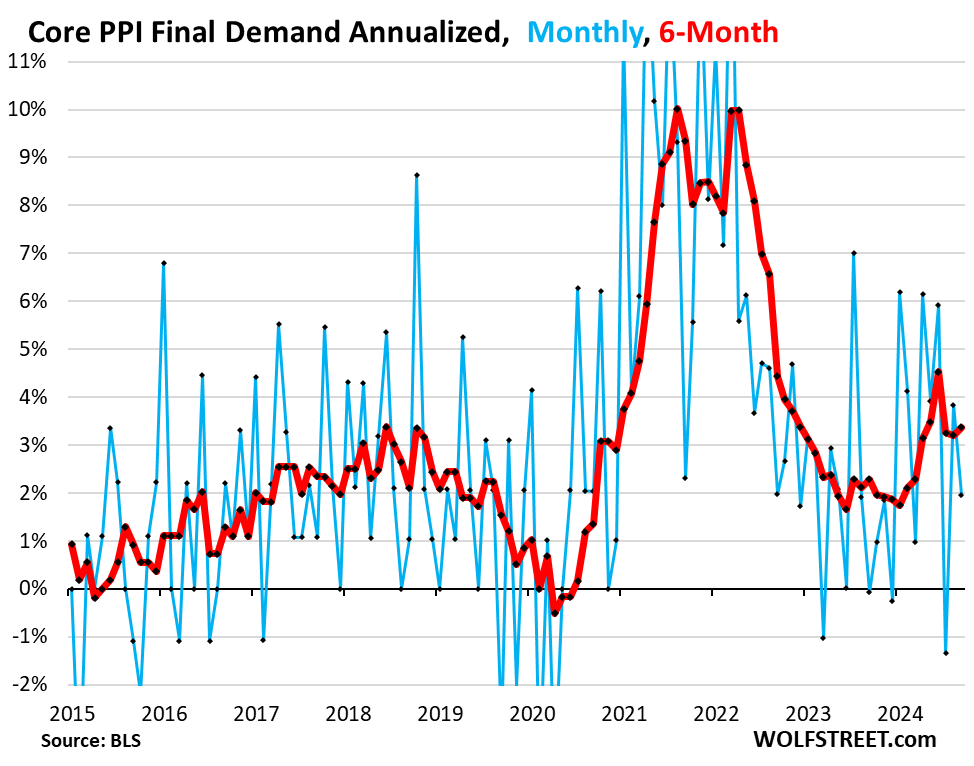

Inflation at the producer level – beyond the plunge in energy prices – has been going in the wrong direction all year, driven by accelerating inflation in services, after benign readings last year.

And on Friday, the core Producer Price Index was made a lot worse by big up-revisions of prior months, which caused the six-month average (red) to accelerate to +3.4% annualized for September. Last year, it had hovered nicely around the 2% line.

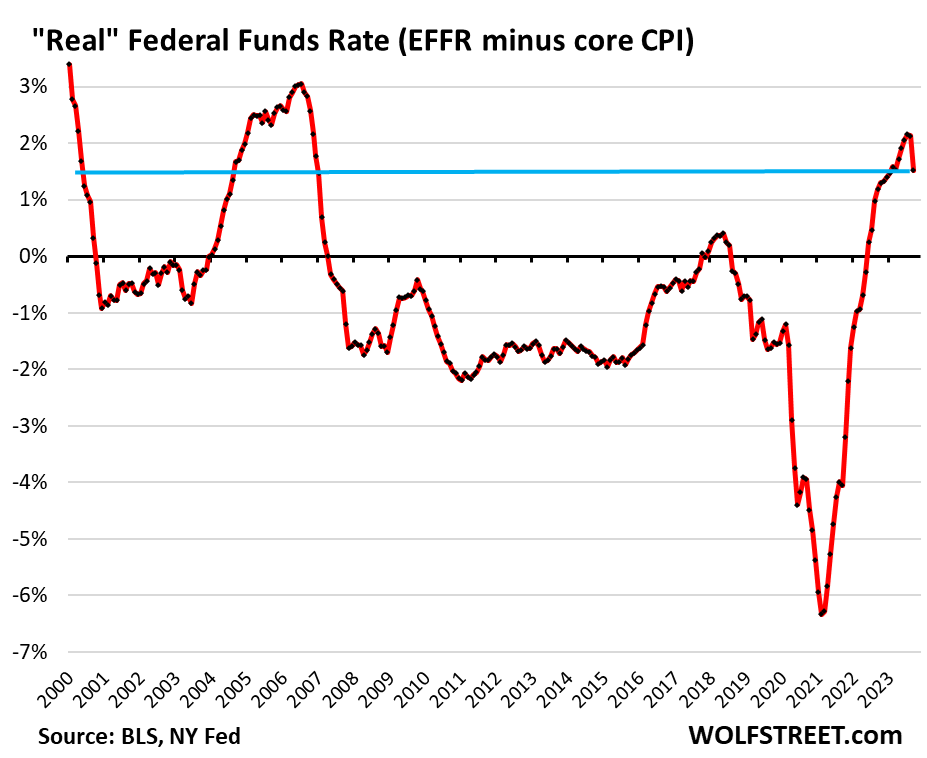

The Fed’s policy rates are still well above inflation rates.

The Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR), which is targeted by the Fed’s policy rates, dropped to 4.83% after the rate cut, so that’s about 1.5 percentage points above the 12-month core CPI inflation rate. EFFR minus core CPI represents the “real” EFFR, adjusted to core CPI inflation.

The zero-line marks the point where the EFFR would equal core CPI. During the ZIRP era following the Financial Crisis, the real EFFR spent most of the time in negative territory. In 2021, as inflation exploded and the Fed was still at near 0% with its rates and doing $120 billion a month in QE, the real EFFR plunged historically deep into the negative. The Fed called this phenomenon “transitory,” and we called the Fed “the most reckless Fed ever” (google it, just for fun):

The assumption by the Fed is that policy rates that are substantially above inflation rates are above some theoretical “neutral” rate, and therefore are “restrictive.”

Fed governors have diverging opinions of where the neutral rate might be, since no one knows since it’s just a conceptual rate, and therefore diverging opinions on just how restrictive the current policy rates are – but they agree that they are restrictive, at least to some extent.

But what we’re seeing in the economic data is that policy rates may not be restrictive after all, that the “neutral” rate may be higher.

Yet the signals diverge.

Some sectors have gotten hit really hard by those higher rates, especially commercial real estate, which has been in a depression for two years. For CRE, which had entered into a frenzy during ZIRP, financial conditions are strangulation-restrictive now. But that may be helpful in wringing out some of the excesses and in repricing properties to where they make economic sense.

Manufacturing, after the boom in manufactured goods during the pandemic, has been about flatlining at a high level.

But other sectors are flying high and are ascending further, including consumers.

At the extreme end of the highflyers, the spectacular bubble in AI triggered a vast investment boom – from construction of powerplants and data-centers – fueled apparently insatiable demand for specialized semiconductors, stimulated hiring and even office leasing, stimulated waves of corporate spending and investment, and waves of investments by venture capital in startups with AI in their descriptions. For anything related to the AI bubble, interest rates appear to be hugely stimulative.

Given where inflation is currently – 12-month core CPI at 3.3% – and where the Fed’s policy rates were before the rate cut – at 5.25% to 5.5% – it made sense to cut rates to bring them closer to the inflation rates, but keeping them well above the inflation rates.

The media has declared victory over inflation, not the Fed.

The problem arises if inflation gets on a consistent path of acceleration. Powell and Fed governors have pointed at this risk many times. They’re fully aware of this risk. They’re leery of inflation going the wrong way again in a sustained manner. Inflation has been going the wrong way in recent months, but for a sustained acceleration, we’d need to see a lot more bad data, given how volatile the data is, to establish a solid trend. And they’re leery of that. They have not declared victory and have said so. But the media has declared victory over inflation, no matter what the Fed or the data say.

If there is an acceleration of inflation, the Fed can pause rate cuts for more wait-and-see. And if incoming data before the November meeting go in that direction, wait-and-see would be a prudent thing to do.

And if wait-and-see doesn’t work in halting the acceleration of inflation, if rates are not restrictive enough to hold inflation down – this likelihood rises with each rate cut – the Fed can hike again. Rate cuts are not permanent. Those scenarios are starting to show up on the horizon again.

The current situation also suggests that higher rates may actually be good for the overall economy, especially over the longer term, including for the reason that a considerable cost of capital fosters better and more disciplined and more productive decision making.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

So this means the government will have to refinance debt at much higher rates than they enjoyed in the recent past, real estate will not enjoy 3% mortgages any time soon, and wall street will not be getting any QE to support the third stock bubble of the past 24 years. I like it!

“real estate will not enjoy 3% mortgages any time soon”

3% mortgages aren’t coming back anytime in our lifetimes.

Which means that if you re-financed during the brief window of 3% mortgages, you’re never moving. Ever. You’re going to play “beat the banks over the head with an aluminum baseball hat” every day and laugh at the schmoes paying 6.5%.

Life happens all the time. Changes in circumstance require changes in location.

So no one will ever die? Or get divorced? We’ve seen inventory rising quite rapidly over the last 2 years, which proves the “no one will ever sell” narrative has been laughably wrong.

The real estate most of us have with a 3% mortgage means we will never worry about interest rates again.

With the appreciation from my house any other purchases will be cash.

I remember sitting in a finance seminar on the late 70’s and the instructor telling us we’d never see rates under 10% again.

And when fixed-rate mortgages disappeared, replaced with adjustable ones, “fixed rate, 30-yr. mortgages were gone forever!”

Two old guys on a bench:

“I wonder how long ‘forever’ is?”

“About 36 months, max.”

“What If There’s No Landing at all, But Flight at Higher Speed and Altitude than Normal, with Higher and Rising Inflation?”

“He who lends what isn’t his’n, pays it back or goes to prison”

A ditty, (maybe just a wishful belief in “equality” under rule of law and the basic fairness of the majority of men…..how could we survive against such incredible odds without cooperating fairly?….and for the millions of years since we evolved from specialized band(s) of rock throwing chimps appx 6-7 M years ago?) from a long time ago which is now proven functionally totally untrue. Yes, Virginia, THROWING IS why we walk upright and have calculating brains.

Isn’t just rocks they are throwing.

Robert (QSLV)

Yeah,

That sign cracked me up when I went to the zoo. Never got to see it, which would have made my day!

You selling fittings? Bad start here, if true.

The debt based economy is a pyramid scheme, based on constantly bringing more and more consumers into the scheme. That is why the establishment freaks out about the declining birth rate and illegally imports millions of immigrants. At the point you no longer have new people coming into the debt based system, it implodes. We are now very near that point.

What’s highly indebted in the US is the government and businesses, not households. Households have deleveraged over the years:

They want inflation. Just not too much that it riles up the masses.

It’s the only way to lower debt to GDP over time.

We know they can’t cut spending or raise taxes.

I think you’ve nailed the only way to lower debt to GDP.

Buy a tiny home. They cost now about what my father paid for

Our big home. Government caused inflation will do the rest and you will soon have a “profit”, and be subject capital gains taxes.

Basically, you never really make a profit on any asset, you just keep up with inflation. Also, there is another form of insidious inflation; when you sell the big home and pay taxes on it, you can only afford to pay for a smaller tiny house. The government has your cake and eats it to.

@Andrew pepper you make a “profit” when your asset increases faster than inflation (the people that bought $50K homes in Palo Alto 50 years ago that are worth $5mm have made a “profit”.

If the home you sold is your primary residence, you don’t have capital gains.

@Cory R only the first $250K of a home sale ($500K if the home is owned by a married couple) so in most areas people don’t pay capital gains tax on a home sale, but almst every long term owner on the SF Peninsula pays some tax if they cash out.

I saw several tiny houses floating in the last FL hurricane.

🛥️

Exactly. Inflation is good for business and government but bad for working stiff. Younger people who just joins the workforce will get the current wages but older people who are at their later part of careers are screwed.

We need to do ratios of hours worked for median wages to purchase the median home to show how much things have changed over the past 40 years.

In 1980 it was 3.5 years of median salary to median house price.

In 2022 it was 5.8 years of median salary to median housing price.

Imagine having to work 2.3 years more to own a home.

That’s not the problem. The problem is that most households can’t qualify for a home loan, certainly in California.

JeffD

“…most households can’t qualify for a home loan”

That’s BS. “Most households” (65%) ALREADY OWN a home – they’re homeowners, and nearly 40% own their homes free and clear without mortgage. A big portion of the renters are “renters of choice,” who rent higher-end houses and apartments/condos because they don’t want to buy. Nearly all multifamily and single-family rentals that have been built over the past 15 years are higher-end and have been built for higher-income renters of choice, most of whom could qualify for a mortgage. Even in California, LOL. You think someone paying $5,000 a month in rent in SF cannot qualify for a mortgage for a house in the suburbs? Go try out a mortgage calculator. They can buy a $700k house in the suburbs, pay $4,200 a month in mortgage payments, and have $800 a month left over to pay property taxes and insurance… Those are the renters of choice. They don’t want to own a house in the suburbs, they want to live in a higher-end place in the middle of SF and not worry about ownership issues and commutes, and have the freedom to move frequently. That’s also great for people who have to stay flexible for their careers. People choose based on their preferences. That’s what America is all about. Just because they choose A doesn’t mean they cannot afford B.

2.3 years more if your net saving your whole salary every year. You’ve got to divide by the fraction you save. So at a 33.3% savings rate that becomes 6.9 years more.

home sizes have doubled as well

https://www.darrinqualman.com/house-size/

We need plenty of 800 -1000 sq ft homes- You would not live in our first home it was 25 year old 600 sq ft mobile home without indoor toilet in northern Minnesota. Now we have an ocean front villa. Every generation thinks they have it tougher than the last it has always been tough and probably always will be –that is life.

I see the builders are starting to build 800 to 1200 sq ft homes again. good.

@topgnome

Parents bought a 950 sq ft house for 30k in 1982. They were making slightly above the median household income.

Who is lining up to build homes at 1.5 the median household income? And what community will allow Levitt to mass produce those 800 sq ft hones again?

@Kurtismayfield a Porsche 911 cost about $30K in 1982, so your parents bought an inexpensive home at the time (the CA median home price was over $100K by then (it topped $100K aroung 1980).

AI,

What makes mentioning ’82 911 price relevant to your response to KM…..unless maybe you would just LOVE to tell everyone here what your vehicle stable since then was worth? Just ballpark it.

Go ahead, you earned it all, and with ZERO help, just your own “hard work”, I’m sure.

Full disclosure: I’m an economic loser and obviously very upset about it.

…to rephrase Paul Simon:

“…one man’s signal is another man’s noise…”

may we all find a better day.

Fully agree. Inflation is good for government because it lowers the real value of the debt. It is good for corporations, because they also hold very large sums of debt and value of their assets value increases. It is good for the vast majority of the adult US population, because they also hold assets. It is bad for the minority who dont have assets or debt.

In early 2023, everybody was talking about hard vs soft landing. SVB collapse changed the picture. Now we have no landing. The extravagant amount of liquidity pushes the system with an enormous thrust, so much that it does not allow any possibility of landing. The current economy is like an airplane which cant land due to an enormous wind.

Senior citizens on a fixed income or relatively fixed income get crushed inflation. That is most of them except the very rich. And they vote.

Nobody thinks they like inflation. Even people who are well off and who are not really affected by inflation are unhappy with inflation. LOL

I have a friend who complains when he goes to the grocery store and pay $20 more a week than they did the previous year. . His car insurance went up 15% YOY. Yet he does not realize that his 401k went up by 25% or $300k and his house value went up $50k thanks partly to inflation.

They want the wealth gains without inflation.

ru82: You are totally right. People are very happy to see their home appreciate 5-10% every year in zillow and brag about it. But they complain when they get a hospital bill 10% higher than last year. People are happy with asset inflation, but not with consumer inflation. But that’s not possible. When assets appreciate, it eventually passes on to goods, services and labor. There is an accumulated asset price inflation ranging from 50% to 500% (depending on the asset type) in five years. And these increases will eventually pass on to consumer inflation. There is no escape.

thank you Trump for taking the m1 money supply from 4 trillion in Jan 2020 to 18 trillion December 2020. that money is still sloshing around. do you think that may have had a little something to do with it.

Going.. fishing?

ru82 and nolanding, respectfully, you’re both right for the wrong reasons. your friend’s 401k is all hypothetical. unless he’s dumb enough to withdraw from it early, where he’ll get taxed and pay a penalty, it doesn’t do him any good to paying his grocery and car insurance bills.

nolanding, people are happy with asset inflation but not cpi inflation. in the balance, the latter is worse for most people, which is why only the wealthy are really happy with the worldwide economy right now. their asset inflation has far outpaced their living needs, which is more cpi, so they’re doing better. most everyone else is either worse off or even.

Inflation is the tool by which government steals the money of the citizens. It is a stealth tax that robs the value of your earned income.

Inflation in short, is a pyramid scheme. It is based on debt, greed, and the ability to spend money you really do not have. Like all pyramid schemes, it works until it doesn’t, and then the whole thing comes crashing down. It is all based on the greater fool theory, that someone down the road is going to pay more for asset than what you paid, and more than it is actually worth. All bubbles pop, and this one is no different.

In the 50’s and 60’s, the average mortgage was 10yrs, and could easily be afforded by a single income blue collar family.

May we consider that reality, by it’s nature, has limits. However, absurdity goes “to infinity and beyond.”

UK and France are announcing spending cuts and or tax increases. Canada is working on tax increases. Isolated cases? Or West deciding to clean up the central governments debt and deficit spending?

World wide debt is $236T. Government debt is 40% or $91T. Current interest rates and on going deficits are challenging governments. Math of it.

Inflation. Spending cuts. Taxes.

Jobs. Adding up to more challenges for people.

Ideally, the West needs to bring the jobs back inhouse.

You are dreaming, the jobs are never coming back. Robots/AI are now cheaper than humans.

Nicko2-

“ …jobs are never coming back.”

The exact jobs that were lost may not come back, but (at least in past cycles,) other jobs have replaced those that were lost.

Consider this depiction voiced a few decades back:

“In 1790, 90 percent of Americans did agricultural work. Agriculture is now in “shambles” because only 2 percent of Americans have farm jobs. In 1970, the telecommunications industry employed 421,000 well-paid switchboard operators. Today “disaster” has hit the telecommunications industry, because there are fewer than 20,000 operators. That’s a 95 percent job loss. The spectacular advances that have raised productivity in the telecommunications industry have made it possible for fewer operators to handle tens of billions of calls at a tiny fraction of the 1970 cost.”

—Walter Williams, George Mason University, pointing out that individual industries cycle, yet the economy advances.

New jobs (in entirely new job categories) replace old jobs.

Respectfully.

I heard the same thing in the 90’s when PCs entered the workforce. More jobs than ever resulted.

…if only aggregate world human population could real-time adjust its approximate numbers peacefully in approximate concert in real-time with that future remunerative employment availability (…oh, no, after YOU, Alphonse…).

may we all find a better day.

Correct. After WW2 many countries had very large debts to deal with. The way out was a combination of inflation, tax rises and trimming down expenditure. It will be the same this time. The USA has been spared this at the moment initial the government deficit is about 50% of tax receipts.

Inflation in the US was mostly the result of the Vietnam war. Inflation began in 1965 with the debasement of US currency by removing silver from the coins and the undermining of the Constitutional requirement to exchange paper money for silver.

The US needed billions to spend in Vietnam, and the taxpayers would not support an above board tax increase to fight a war the government could not even explain.

They needed a stealth tax, which is what inflation is.

Pre-1940, Japan’s exchange rate was about 2 or 3 yen to the dollar. Post-war, it went to 360 to the dollar.

I hope the feds realize that inflation isn’t under control and raise rates by 1/4 point early November!

Loved: “The media has declared victory over inflation, not the Fed.” We need victory over the Fed, and its front-running, self-serving BOG Alpha Hotels.

1) It’s an election year. WE wasted DUCs/DUCs on $2.5 NG. CL and grain prices might rise, bc US farmers cut too much to adjust.

2) SPX might drop to 4,800/4,600. It might dent real personal income, but not by much. Retired boomers might suffer under 2.5% COLA. SS minus [Rent + food] = zero. SS – [OER + Food] < zero.

3) The Fed will stay the course, until EFFR – CPI < zero. Negative Rates, to give the next "federalist" administration a chance to cut debt.

4) Highly skilled workers wages will rise. Tax collection will fill the gov coffer. Under the US constitution floods and natural disasters will be

covered by the states and private co not by the federal gov. GW, TR, Coolidge… It's inhumane, but a $40T/$50T debt instead of $30T/$25T debt is more inhumane.

Sure would have been nice if the Fed had the same patience with a cut as they did when raising rates. One bad preliminary labor report and BAM, 50 bps cut. On the way up, they would have waited for 2 or 3 sequential reports before making a change in the rate. Nevertheless, we’re all monday-morning quarterbacking on their behalf, and it’s a tough job they have.

However, The mainstream media is the enemy of the people in this country.

“Nevertheless, we’re all monday-morning quarterbacking on their behalf, and it’s a tough job they have.”

Perhaps so, but when somebody consistently and for a long time does their job badly, we give them a label. That label is “incompetent.”

Regardless of how tough a job is, there’s always somebody out there, somewhere, competent to do it. Whoever and wherever those people are, they’re not working at the Federal Reserve..

A big AMEN!

B

Perfect summary of the Fed.

Further to the point, many of us were actually Saturday quarterbacking. And Friday. And Thursday. We said all along that rate raises didn’t go far enough or fast enough, and that dropping right now would be too soon.

So, I think we’ve earned some Monday morning commentary.

Yes, I should have mentioned that. And before that, many of us were Sunday quarterbacking (not that anybody was listening to us, heaven knows) during the entire ghastly ongoing policy error of the pandemic era.

They need rules based policy like the Taylor Rule, which would have produced rates around 10% back in 2022. Or better yet, end the Fed, the US economy did demonstrably better prior to its existence with far less inflation.

And rules prohibiting QE forever and mandating prompt irreversible QT.

I feel like someday soon they could replace the fed with ai. It would then actually be data dependent and could find the true neutral rate.

That being said we would actually need good data for it to react to. These revisions make me think some people should be fired. What’s the point of producing data that can’t be relied on.

I have an analogy, it’s not perfect. But first I would like to thank Wolf for his level headed analysis because I don’t dismiss what he says while simultaneously considering (is not fully believing) the following:

You go to a building, sign says bank. You think “primary purpose is safe place to park/ borrow money.”

Go to a campus, sign says college. You think “primary purpose is to educate people.”

Go to a church, sign says something silly, but you think “primary purpose is moral regulation.”

Go to an airport, sign says international flights, you think “primary purpose is to transport people quickly.”

And you would be wrong in each and every example. Why? Expectation management. Analysis begins and ends at the sign. How quickly the human mind substitutes a concept for reality!

The primary purpose for each and every one of these institutions is to make money. The sign merely indicates how they do it. They all fail if they don’t.

The fed is not incompetent. Their mission statement is a sign: 2% inflation and full employment. Yet?

“Must be incompetence, can’t even do what’s clearly spelled out on the damn sign.”

Most are continually shocked when institutions repeatedly fail to perform signage.

Follow the money. Trust is easily deceived by greed.

“But the sign says….” Yeah, I know. Life becomes pretty stressful without them.

Primary purpose of the Fed is to protect the bond market and demand for Treasuries.

Nope, its primary purpose is to provide emergency liquidity to the banks in case they face a run-on-the-bank. They’re the lender-of-last-resort to the banking system to provide stability to the banking system.

Yes, it is a tough job to steal the money of the working people and give it to the corporations and wealthy, but someone has to do it… The money for those mega mansions, private jets, and super yachts has to come from somewhere you know….

Dirty – …imho, the current issue with the ‘news’ side of ‘mainstream media’, thanks (in the U.S.) to the Reagan-era suspension of the ‘Fairness Doctrine’, coupled with the massive technical phenomenon of the interweb, is that it has morphed wholesale (for the sake of its fiscal survival), into the current form that gives the majority of us exactly what we, frankly, have always demanded: confirmation-biasing ‘entertainment’…

more than ever, to reprise R.A. Heinlein’s aphorism:

“…self-deception is the root of all evil…”

(How often do we each gaze into a mirror crack’d?).

may we all find a better day.

Dr. Daniel L. Thornton, May 12, 2022:

“However, on March 26, 2020, the Board of Governors reduced the reserve requirement on checkable deposits to zero. This action ended the Fed’s ability to control M1. In February 2021 the Board redefined M1 so that M1 and M2 are very nearly identical. Consequently, it makes little sense to distinguish between them.

In any event, the checkable deposit portion of M2 cannot be controlled now because there are no longer reserve requirements on these deposits. Here is the reason the Fed cannot control these deposits.”

Since then largest handful of banks run on about 2.5% reserves and the rest are holding around 5% reserves.

Seems to me we are in a “Tinkerbell” economy. Housing, stocks, crypto, and other assets will stay overvalued if enough of us just keep clapping.

What if there is slower flight, at volatile altitudes, and higher currency inflation, STAGFLATION?

Theoretically. But that’s not where we are. Check out the data in the article.

IMHO, this latest commentary by Wolf does an excellent job of coherently assembling several key puzzle pieces to explain the reality of where inflation may really be heading in the US. What I’m now waiting to see, though, is how the bond market continues to react in the coming months, considering all of these inflationary indicators along with anticipated borrowing by the Treasury. Have the bond vigilantes of yesteryear all moved on, or are they still with us and poised to act?

During the early phases of QE starting in late 2008, the already beaten-up and decimated bond vigilantes were taken out the back and summarily shot. There are none left.

It took two decades to give rise to them in the 1970s and 1980s, when big bond investors were mauled year after year by rising inflation, and ever higher interest rates that left them holding the bag year after year on their previously purchased bonds. And they were furious because inflation wasn’t brought under control. And then in the mid-1980s, after inflation had started to fall, government deficits shot through the roof, and big bond investors had had it.

They didn’t want to buy Treasury securities and had to be enticed with much higher yields, in relationship to inflation, to buy them, because they’d gotten beaten up so badly for so long by inflation and rising yields, and now there was this scary ballooning US debt – all this new supply coming on the market – and they were tired of losing money, and they didn’t trust that the deficit issues would ever be resolved, and they saw big risks in that, for which they wanted to be compensated.

And so Treasury yields remained stubbornly high in relation to inflation into the 1990s. It wasn’t until Congress and the Clinton White House succeeded in visibly bringing the deficit down that longer-term Treasury yields dropped in relationship to inflation.

The term “bond vigilantes” was coined in the early 1990s to describe big institutional bond investors who’d gotten tired of getting beaten up, and they demanded higher yields in return for their pains and for the risks posed by the through-the-roof deficits before the early 1990s.

I could buy government bonds here. But I am scared of US debt. What do you think? Cam I still buy 90 day bills and see the crash coming in time?

If you buy long-term US government Treasury securities, the thing you have to be scared of is higher long-term interest rates in the future. That’s duration risk. It applies to all long-term bonds, no matter what. It means you will get face value of the bond at maturity, and you will collect the coupon interest along the way. But if you try to sell the bond after interest rates rise, you will get less than you paid for it. But there is no credit risk with US Treasury securities (government defaults on the bonds).

I do not own any long term US government debt and refuse to buy any. Does that make me a bond vigilante?

If you run a $100-billion bond fund and refuse to buy US government debt, yes.

If not, you’re just a retail investor and don’t count.

Wolf, if I’m shorting bonds, does that make me a bond vigilante?

/s, kinda…

If there’s no landing at all, well then, you run out of fuel and crash.

I knew that sooner or later someone would point out the limits of Powell’s metaphor by extending it ad absurdum. That’s easy to do with metaphors.

It’s a difficult task on the internet, but I was being facetious. Well, not totally.

I will extend the absurdity by pointing out the thin air at this altitude and the distance from our landing strip is growing.

The fat lady sitting next to me up here is adjusting well, I believe she is about to start singing. Which means a new Normal is upon us.

Make sure you “don your own mask before assisting the fat lady…”

And No Smoking!

We’re flying a 777ER. Plenty of fuel onboard.

I see the article as a fair description of the reality. Thanks Wolf.

Not an easy job to be FED. They are really trying to act on actual data, rather than some hidden agenda.

Some complaining that FEDs are not detailing what are their future steps (aka not transparent). It would be alarming if they have some set, pre-prepared path. They are transparent to me ie act on data.

“They are really trying to act on actual data, rather than some hidden agenda.”

In my opinion, it was easier to make that argument prior to the 50 basis point cut.

Yeah, looking back, they overshoot. 0.25 would be better, knowing what we know today.

Knowing what we know today should have been no cut.

I otherwise agree the 25 point cut should have been the data driven decision at the time.

Guys, you need to read at least the start of the article. The up-tick in the data started 11 days *after* the rate decision.

You have it exactly backwards. The doctrine of “forward guidance” currently followed by the Fed, under which policy moves are telegraphed well ahead of time and surprises are avoided lest anybody spook the markets, has been a fantastically stupid and destructive one these past few years. They are all too willing to detail what their future steps will be, and this takes away their ability to be agile and avoid locking themselves into the wrong stance.

Locking themselves into the wrong stance is exactly what happened during the pandemic. If they had actually allowed themselves to “act on data,” they wouldn’t have felt compelled to keep shoveling hundreds of billions of printed dollars per month into a clearly white hot economy in 2021 and 2022 while holding interest rates at zero.

“Acting on data” would have meant updating their priors in real time as data came in showing as early as late 2020 that the predicted pandemic economic holocaust had not come to pass, and that consumers and businesses and investors had more money than they knew what to do with–and pivoting appropriately *at that time*, not a year and a half later.

Inflation was only transitory, dontcha know?

Yup. Everything’s transitory if you wait long enough.

Bingo. Their concern in the direction of a fall in assets outweighs their concern about inflation above their bogus illegal 2% target by an order of magnitude. Watch what they do, not what they say.

“Their concern..”

That seems reasonable. But could be totally incorrect.

Absolutely watch what they do.

Just don’t be so certain about why they do it. You actually don’t know. Unresolved complexity is difficult to accept.

Worse, “the not what they say” part. Nearly all assumptions are made primarily by analyzing what was said. Powell says a lot, and Wolf does a good job interpreting. But in the comments, people immediately defer right back to their own opinions.

You would think we all should be billionaires by now by how certain we are.

It says right here on your license “Most wreckless fed”. I’m going to ask you to step out of the vehicle.

“Most wreckless bank” is not my choice for depositing my money.

HT – ah, the auto-whatever smoke continues it’s waft over the lingua franca (…would prefer to keep my money in a firm that had never encountered a wreck to one that had one-to-several due to its recklessness, but that’s just me…).

may we all, (your good self excluded by request) find a better day).

The question is what happens to Mr Market if there isn’t another cut. Do we say that Powell is listening to the data after a market correction?

The fact that the real Fed rate was negative for 17 out of the last 24 years is interesting considering how long we made it without things going to heck.

I think the Fed et al have been underestimating productivity increases for a long time, so maybe the Covid shutdowns and the shuttering of much of the productive economy killed the gains we have been living on.

I know everyone who generated paperwork during the lockdowns felt productive, but it’s not the same thing as making spoons :D

Fed Open Market Committee meeting transcript from July 2 & 3, 1996, page 46, for a little chat between Janet and the Maestro, no tin foil hats required.

MS. YELLEN. I would agree with your conclusion that we need

higher productivity growth, but I have not seen any evidence that

convinces me that we would get it. But certainly if we did get it, or

if productivity growth were higher, it would be easier by an order of

magnitude to live with price stability.

CHAIRMAN GREENSPAN. We do see significant acceleration in

productivity in the anecdotal evidence and in the manufacturing area

where our ability to measure is relatively good. We can see that

acceleration if we look at individual manufacturing industries. It is

our macro data that are giving us the 1 percent productivity growth

for the combination of gross industrial product and gross

nonindustrial product, which do not show this phenomenon.

MS. YELLEN. One could argue that we have roughly a 1 percent

bias in the CPI so that right now we have, say, 2 percent productivity

growth and 2 percent core inflation.

CHAIRMAN GREENSPAN. We have not had such productivity growth

for long.

MS. YELLEN. Such productivity growth would mean that we are

living successfully with 2 percent inflation.

CHAIRMAN GREENSPAN. That is exactly the point. That is

another way of looking at it.

MS. YELLEN. Because productivity growth is really higher

than we have measured it.

CHAIRMAN GREENSPAN. In fact there is obviously an exact,

one-to-one tradeoff. That is, we can reach price stability either by

driving down the inflation rate and getting productivity to bounce up

or by revising down the inflation figures and producing higher

productivity! [Laughter]

MS. YELLEN. I am perfectly happy with the last view.

Manufacturing has been a very small part of the global economy for quite some time now. It’s not hard to look up.

Worldwide manufacturing is one-sixth of all economic activity and in the US about one tenth, and has been since before 2000.

If you’re willing to tell the vast majority of the world’s workers they’re not doing anything productive, you’re welcome to, but that’s not likely to be too well received.

“a considerable cost of capital fosters better and more disciplined and more productive decision making.” – this is so true! ZIRP enabled moral hazard.

If productivity was at -2% or worse, ZIRP wouldn’t necessarily cause moral hazard. Same with sending checks to everyone if productivity has collapsed.

If expectations are that money is now “free”, than that’s a different matter. People’s expectations are usually exaggerated.

then, not than

Wolf,

It’s difficult to tell whether high rates are good for the economy. It could be that very high deficits have been good the for economy. Those two things have been saddled together, so teasing the effect of one out from the other….guesswork.

My guess would be yes, they are, so long as debt is limited so as not to create too large of an interest rate load (recognizing that some of the interest paid is income to taxpayers, and thus recycled).

Gatto – …have always felt high deficits are the ‘socialize the risk’ half of the equation…

may we all find a better day.

Once the stock market rolls over and home prices normalize, spending will collapse. Bernanke said he used QE to lift asset prices and produce the wealth effect. It works in both directions.

When the Nasdaq plunged by 78% from March 2000 to Oct 2002, and the S&P 500 by 50%, it created only a minor brief slowdown in spending in the overall US economy. But in regions that were heavily tied to the Nasdaq, spending got hit much harder (the big example was the SF Bay Area, but Boston and other places also saw this phenomenon).

Fortunately the smartest guys in the room created trillions in bogus mortgages and sold the slop around the word to turn housing into another financialization “product”. Many of those banksters are living the good life in their $40,000,000 beach homes and those 7,000,000 families that lost their homes are more than happy to cut their grass for them.

“Grandpa, can you read me the story about the Fairy Fed that watches over us?”

Aren’t stock market valuations even more stretched now than they were in 2019-2000?

If the Fed’s activity prior to EFFR rise and QT was “most reckless ever,” that seems to suggest Putter’s opinion is well-founded.

The late Martin Zweig’s 1990’s research on price swings in the Dow Industrials Average seems relevant: the market, over his research period of about 100 years, goes through a 50%+ decline roughly every 10 years.

Emphasis on word “roughly!”

All seems great for now with increased wages and savings but I wonder how that can all go wrong. Not in a doomer scenario but wondering should employment turn down how long will that extra savings carry somebody or a family? There are only so many ways to cut expenses as some many are fixed and necessary. I just had to get a new phone and my son needs 4 wisdom teeth out. Despite good insurance it still is going to drain the accounts some.

I guess my point is once we hit a bump, the numbers can go from rosy to bad fairly quickly. Nothing positive will happen in Congress so have to hope the good times continue to roll, if the cost of shelter and other necessary services is indeed considered good times.

https://danericselliottwaves.org/

Elliott Wave analysis shows top is imminent.

Christ, do those people still exist? “Clearly, this is the top and prices can only go down from here, unless this is wave #2 of a three-wave cycle, in which case prices must go sideways, also it might be the third wave of the first set of a three-set metawave, in which cases prices can only go up from here.”

Just wait until peak “peak oil”

…surf’s up???

may we all find a better day.

“The current situation also suggests that higher rates may actually be good for the overall economy, especially over the longer term, including for the reason that a considerable cost of capital fosters better and more disciplined and more productive decision making.” Wonder if this logic will how true to the stock market and it’s addiction to ZIRP? My popcorn is ready.

The stock market is going through the roof with ZIRP long in the rear-view mirror. Indeed, it is going through the roof with quantitative tightening and historically normative interest rates.

“But what we’re seeing in the economic data is that policy rates may not be restrictive after all, that the “neutral” rate may be higher.”

Yes, that’s exactly what we’re seeing. They Fed clearly knows the neutral rate for the foreseeable future is higher than 2%. Unfortunately, they’re very reluctant to admit it at a FMOC meeting or to put a number to it: 2.5%, 3% or possibly higher.

In doing so, this is a classic example of the Tail (markets) wagging the Dog (Fed). And all of this is an effort to get us past the election cycle. I firmly believe we’ll get a firmer answer from the Fed in January, where maybe they’ll really put Congress on notice about what higher inflation means for the nation’s national debt & interest expense.

“The Fed clearly knows the neutral rate for the foreseeable future is higher than 2%.”

Correct, NO ONE at the Fed sees neutral at 2%, that’s history. Every single one of the 19 participants see neutral above 2.0%. We know that from the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) which they release at every other meeting.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20240918.htm

The 19 participants rate the longer run neutral between, at the low end 2.375% (1 participant) and at the high end 3.75% (1 participant). Everyone else is between 2.375% and 3.75%. The median is 2.9% as of Sept, This median has crept up at every SEP (four times a year) and may be 3.0% in Dec.

And obviously, we discussed this here:

https://wolfstreet.com/2024/09/18/fed-cuts-by-50-basis-points-to-5-0-top-of-range-sees-additional-cut-of-50-basis-points-in-2024-qt-continues/

I feel like a pirate… got my wooden leg and eye patch… argh.

But I’m not a pirate I’m a brainwashed American sucker that thinks I know something….

I went back in time to see “the most wreck less fed ever” comment and there it was, speaking of Powell&friends of course. Looking for a words worse than “most wreckless” and not finding it.

Enjoyable reading..thank you.

I wish I could understand you every time. I feel lots of wisdom there.

Hello biker, that’s what I think of wolf articles, I don’t understand much of this finance/money thing, but his wisdom, humor in his articles and comments are apparent.

I guess you come for the Wolf and not the street.

We might get a pause if data is consistently bad… but I don’t see the fed raising unless we hit like 7% cpi consistently for months. They want to cut. They’re terrified of being blamed for a recession.

“They’re terrified of being blamed for a recession.”

And they’re not terrified of losing control of the yield curve and being forced to do QE again?

Fed cuts FFR by 50bps and the 10-year goes UP by 50bps – what does that tell you?

It probably means inflation expectations are much higher than the Fed believes them to be. The Fed should increase QT dramatically if they want people to “feel” less money sloshing around. How about $150B a month?

They’re watching the un-inversion of the yield curve, and I think they like what they’re seeing, in terms of the yield curve. An inverted yield curve is an anomaly. it always eventually un-inverts with long-term yields substantially higher than short-term yields. That’s a process, and it takes a while. If the Fed’s policy rates eventually drop to 4%, you’d expect short-term yields in that range and the 10-year yield at around 5-6% in a healthy yield curve.

I agree that sounds about right:

4% FFR

4.5% 2-year

5-6% 10-year

6+% 30-year

Fed doesn’t mind an orderly rise in long bond yields, but they don’t want them going up too much…

They were never forced to do QE, and they will never be forced to do QE. QE was always a choice that they made. A bad one, each time.

They dropped rates to zero, effectively, yet the economy remained punk. So, they tried QE. Still no traction. Then QE 2, etc. They were trying to kick-start the economy but couldn’t get it going.

When people look back, they only see what they want to see; ignore the stuff they don’t want to see.

Really great well balanced analysis of where we are right now. I think the Fed is well aware of the risks on both sides of the ledger and has so far moved appropriately, independently of how the cheerleaders or doomsayers interpret it.

Are you insane? They unnecessarily bought MBS in 2021 by the hundreds of billions as home prices went up 40%, diddled for an entire year with 9% inflation with their purposefully blind “transitory” crap, if anyone in the private sector had that track record they would be out on their ear panhandling for spare change, not patting themselves on the back in Jackson Hole and Fed splaining and gas lighting people who can’t buy a home in Boise or Nashville.

Wolf,

In articles last year, you correctly pointed out that services inflation was particularly sticky and wouldn’t just go away. This really resonated with me, as I hadn’t really thought about it, but it makes complete sense: services are paying for someone else’s labor, and people would resist giving back pay increases despite falling costs elsewhere.

I love how data-driven you are and how you avoid getting attached to a narrative – however, your writing about sticky services inflation is why I was so critical of the Fed’s rate cut in recent comments on your articles about it. I still feel they should have ‘looked through’ that bad (pre-revision) unemployment data.

While there are certainly a lot of whiny comments about the Fed on here, I think the general ‘vibe’ of some of those recent comments isn’t too far off base: why cut rates when stocks, the economy, spending, etc is all chugging along just fine?

It’s also really tough to see a recession happening with energy being so cheap right now.

At least QT is continuing on track. Because it does seem the plane will keep flying, higher for longer.

Insanity stock bubble update: S&P 500 market capitalization now $48.789 Trillion. That is $48,789,000,000,000. That is also record territory for market cap/GDP. That would equate to $6,100 for every man, woman and child on the planet (based on world population of 8 billion.) That is just the S&P 500, not all US equities.

Tesla has dropped to the #11 spot in the weighting of the index. Broadcom is now #7, and Eli Lilly & Co. is now #10. Both Broadcom and Lilly have P/E ratios over 100. Just my opinion, but there is something very wrong if the Fed continues to lower interest rates with stock market valuations in Looney Land.

May be the “wealth effect” popularised by the Nobel Idiot is working given the GDP numbers

Nobel committee loves irony, hence Bernanke for economics and a former recent POTUS who had done precisely nothing for peace prize. Next up, maybe someone on TikTok for literature?

It is the idiot level PE ratios that give the game away (at a time of unprecedentedly high total debt – corp, gov, everything) – somehow earnings are supposed to *both* grow at record rates *and* service record total debt.

Right…

You can go stock by stock down the SP 500 and see who is smoking crack by their PE ratios (and that is before getting into how overstated the “E” may be in most cases).

Actually, the banks’ PEs are instructive here.

They are relatively low precisely because expected future losses (defaults on loans owed to them) are expected to surge in the future…gutting their earnings, lowering their PE ratio, today.

But various other stocks (no matter how enormous or besieged) have PEs at 2-4 times historic norms, despite unprecedentedly high levels of debt in the US/dollar system as a whole – but that latter fact could *never* affect future earnings…

nvidia has a pe of 65 and apple of 35. they’d have to grow to $7 trillion valuations for these numbers to make sense, lolzer.

Agreed.

PEs imply certain levels of future growth (rates and, ultimately, levels) – putting those implied numbers in the context of *existing*, *actual* levels of much larger entities (states, nations) reveals the absurdity of given PE levels (especially among larger companies – whose high level of absolute earnings already reflects high levels of market penetration – which cannot scale up by the implied levels without the discovery of a duplicate Earth…)

I’m still hunting around for the formulas that directly tie PE levels to implied growth rate (at some given level of interest rates) – they are going to be some variant on the Gordon Growth Model (which ties valuation to growth of dividends…whcih come out of earnings).

Short version, TL:DR – Nothing can grow to the sky.

…still, when the currently-reigning paradigm appears to dictate no serious attempts to determine real ‘growth’ beyond the next quarter, whatwouldja expect?

may we all find a better day.

Anyone under 50 isn’t prepared for a late 80s-90s interest rate environment if the economy is really this hot. Short term money will be 5-6%. Ten year at 6.5, 30 at 7, mortgages for GOOD borrowers at 7.5-8. Forget about car loans. 10% easy.

Maybe with 10, 15, 20 million new immigrants all wanting their piece of the dream things are getting hot and it doesn’t matter if the Fed thinks it’s lowering rates – the bond market will laugh in their face. 6%+ ten years sound great to me.

I made a slightly less aggressive prediction of yields in a comment above, but it wouldn’t surprise me if your quoted rates came into fruition.

Personally I would like to see Long term rates go much higher than current levels. Hoping to see those sky rockets asset prices to com down to earthly levels. But what you are saying doesn’t seem so likely with FED so much supporting. US Treasuries adjusted their Bills % Vs Notes & Bonds. So longer rates were suppressed from October 2023. We hit 10 year 5% for a day may be. FED also tweaked/slowed QT plans from June 2024 in order to help US Treasury. Q3 refunding announcements clearly said because of FED is slowing down QT, they don’t need huge issuance from Market. That helped again to suppress long term rates.

Little misleading slowdown in Labor Market and FED went with 50 BP cut.

So we can see what FED is doing.

I am not saying there is any conspiracy theory and all to help any party.

I just feel FED changed its overall approach to economy and monetary policy after 2008.

Look at Foreign Govts still lending out money to US at 4% for 10 year.

“Foreign Govts still lending out money to US at 4% for 10 year.”

Those foreign gov’ts are getting 4% per year, AND the ability to use those loans (treasuries) as collateral for a dollar loan FROM the Fed.

Look at what is being built in America – dense condos in every major city. People who are starting out overwhelmingly aren’t buying single family homes in the suburbs. They may not be buying at all in fact. Look at how cities are densifiying including 60 story offices now on the table at becoming residential apts. I also brought up how at older age, people are also making another choice. If mortgage rates are @ 10% it may be that it largely will affect just people who want to have kids. Given the state of western world, I could certainly believe “the system” would be making another barrier to creating a family.

There is a signal being sent, unconsciously maybe, that we are headed somewhere else from where we have been.

someGuy – …might recall a longstanding demographic-trend observation of ‘native’ population decreases in ‘first-world’ countries from the late 20th century onward…

may we all find a better day.

Powell watched Elon & SpaceX today. He’s pumped now. A soft landing is possible.

Inflation? Inflation? What, me worry? Why worry about inflation when the ‘bosses’ can just print money like toilet paper. We’ll all be millionaires! I want my check TOMORROW, before all you dolts get yours.

Remember, a lot of Zimbabweans were millionaires.

This is an awesome comment. I think it summarizes the fed policy for last 15 years.

“…it summarizes the fed policy for last 15 years.”

Should read: “Fed policy from x… through 2021.” Because in early 2022, the Fed started hiking and in mid-2022, it started QT. QT = money destruction, opposite of QE money creation. The Fed has so far destroyed about $2 trillion through QT, and it’s ongoing.

https://wolfstreet.com/2024/10/03/fed-balance-sheet-qt-66-billion-in-sept-1-92-trillion-from-peak-to-7-05-trillion-back-to-may-2020-below-7-trillion-in-1-2-months/

You are right. I should say “between late-2008 and mid-2022”. Since mid-2022, it reversed this policy, though it will still take time to re-balance.

Does buying stocks provide a good hedge to inflation? Profits are soaring. People are spending like drunk sailors. Houses are at least 10 years ahead of their normal appreciation so what do you buy. I think it’s EFT time.

Typically…yes. A company that never increases production. Lets say it makes 1000 widgets a year. If inflation is 10% and they can pass the 10% inflation onto the customer and sell 1000 widgets the next year, they will see their revenue will grow 10% and their EPS will also grow without even selling more product. The stock will reflect these growth metrics.

Unless the cost of inputs and other expenses go up 10%.

“The current situation also suggests that higher rates may actually be good for the overall economy, especially over the longer term, including for the reason that a considerable cost of capital fosters better and more disciplined and more productive decision making”

If the Fed understands this at least now, it means that it took the idiots at the Fed a decade and half (2009-2024) to understand this. Being an unaccountable Idiot, with a fat paycheck and who can justify anything, is comfortable for the idiot but not for the country.

I think the increase in the savings rate is misleading because in order to preserve the value of their savings, savers must add to their savings at at least the rate of inflation. For this reason, a good proportion (perhaps over 100% before tax) of the interest paid on savings must be itself saved in order to preserve the underlying value of the savings.

That’s BS. The savings rate is a percentage (rate) not a dollar figure.

savings rate % = (disposable $ income minus total $ spending)/disposable $ income.

And all three $ figures are adjusted for inflation because these are inflation adjusted figures. So that 5% savings rate is 5% of inflation adjusted figures.

WRT to inflation Simon White Bloomberg article today was warning of inflation shock imminent … short quote from article:

“The net saving between the household, corporate, foreign and government sectors must sum to zero. That leads to the Kalecki-Levy equation for corporate profits, which for the US we can boil down to the government and household sectors.

Simply put, the more the government spends, and the less households save, the greater proportion of this income trickles to the corporate sector and drives profits.”

What goes up must come back down.

No it doesn’t. See prices of services.

It was said many times to home buyers to go on a strike. Not sure how many said to go on strike for buying services.

I kind of have trained myself to cringe when spending on them. I was a fool for years to give my bikes to pro bike mechanics. They have been charging $$$ and “need to wait”. Recently I have switched to full DIY service. That should help the landing LOL

Just make sure you get good tools and see that as an investment. I see many janky “diy” bike stuff that is horrid. Get two good torque wrenches (1/4” micro and std 3/8”). I like Proto.

There is so much good info online from real resources including the OEM (Shimano has great manuals as does campy) and Park Tools has good tutorials

Yeap. I guess what was holding me back was the need for a good stand. Just I’m minimalist and having more stuff makes me feel a slave to it. If I can service Fox forks later at some moment is still an open question.

The same goes for anything really. Learn how to fix and maintain stuff yourself. Buy the tools (sure upfront cost is there), but you expand your horizons and learn new skills. Nothing is more satisfying than fixing it yourself.

Absolutely. DIY means also being in control.

The bike was just an example. Yesterday I did again my haircut. Started when covid attacked.

The last major dyi/friend bike project was to fix compromised carbon frame with fibre strides.

> The current situation also suggests that higher rates may actually be good for the overall economy, especially over the longer term, including for the reason that a considerable cost of capital fosters better and more disciplined and more productive decision making.

Amen to this, the economy is close to what we had in 2019 now. Status quo will not hurt most.

MW: Boeing to lay off thousands of workers, warns of quarterly loss and weaker sales

Yes, a strike has shut Boeing down for a month now — the union, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, rejected Boeing’s sweetened offer of a 30% pay increase over four years. That strike and rejection of Boeing’s offer confirms the rising wages data here. Other unions too have been rejecting huge pay increases, if that tells you something.

That Longshoreman deal just makes every union in the country realize how much they have been screwed. I expect more public sector union fights in the future as they see the government’s revenues increase.

…irony sidebar-underpaid Longshoreman finally getting pay increases for handlinghigh volumes of imported products that were mostly-offshored from ‘Murican industry workers long ago…(…but that’s okay, more automation coming for the workers remaining on all sides of the ponds…).

may we all find a better day.

So, we seem to be in an inflationary boom, how long can such a thing last? What could kill it?

@wolf richter

HIGHER 👏 FOR 👏 LONGER

what higher for longer ? Powell already cut un needed 50 bps and would cut more.

Inflation and interest rates on duration.

10-year UP 50bps since the FFR cut.

The Fed blinked, Jay knows this and the bond market is reminding him that unless the Fed is going to start buying again, rates need to go up and CONgress needs to get its shit together. Higher for longer. Definitely curious about what comes out of the BRICS meeting. Trust is the only reason any dollar strength remains.

Interesting times.

‘Energy prices have plunged, and that has papered over the problems beyond energy.”

I have no idea what he eventual outcome will be but energy usage is increasing a lot but much of the increase is being shifted to green. With the government subsidizing much of this cost transition (30% to 50%) tax cuts for solar,wind. EV car tax credits. U.S. fossil fuel producers are producing records amount of oil and nat gas.

What happens when the government decides to reduce or stop paying green subsidies. Maybe they will never be able to as energy prices could rise fast? The subsidies are not stopping anytime soon but that is my what if questions for energy.

We are lucky that energy prices have been so tame the past 10 years when compared to normal inflation.

“energy usage is increasing”

Wolf,

In the past, I recall you’ve shared graphs showing US electricity demand being roughly stagnant over the last ~decade, presumably due to increases in efficiency offsetting increased # of electronics being used.

But recently, I’ve seen a number of articles suggesting a big increase in future demand from AI and data centers generally. Do you think this thesis holds water?

Your correct. U.S. Energy consumption has been flat and dropping. Electricity consumption has taken off over the past year in the US and globally.

Luckly, the US is producing more energy than we need and thus keeping a lid on energy price inflation.

From the IEA:

————————

U.S. energy production has been greater than U.S. energy consumption in recent years

U.S. total annual energy production has exceeded total annual energy consumption since 2019. In 2023, production was about 102.83 quads and consumption was 93.59 quads.

Fossil fuels—petroleum, natural gas, and coal—accounted for about 84% of total U.S. primary energy production in 2023.

Seems like the flat electricity consumption era ended with 2021. In 2022, electricity consumption jumped to a new record. In 2023, it dipped a little to the second highest ever. Electricity consumption can be pushed up by very hot summers in a big part of the country (which happened in 2022). But consumption is definitely up from the wobbly flat line it had been on between 2007 and 2021. AI data centers, EVs, and maybe even crypto mining are starting to push it higher.

I’ll post my annual update at the end of February, when the preliminary data for 2024 comes out. My gut feeling is that it will be a record, though 2024 wasn’t all that hot. This is the one for 2023:

https://wolfstreet.com/2024/02/27/u-s-electricity-generation-by-source-in-2023-natural-gas-coal-nuclear-wind-hydro-solar-geothermal-biomass-petroleum/

I’d like to purchase a one way ticket to nowhere, with no landing please.

There’s been increasing comments lately about disconnects between govt economic reports and mainstream media headlines serving up inaccurate analysis assumptions.

One possible explanation is ai misbehavior — which is possible due to the lack of intelligence that ai has. Unwittingly, there’s also the possibility of robotic journalists simply being lazy and untrained and unable to differentiate an ai summation against actual analysis — but for the most part, the media is sloppy — often thriving on ambiguity and misinterpretation — creating an environment of instability.

Look no further than the Fed in this game of jawboning ambiguity, where the confusion game plays perfectly into wall street hedging and amplifying fear and hate for profit.

The no landing narrative suspends us in a belief that we have no destination, because we’re locked into a polarized political world that apparently needs to be balanced between lies that succeed in pleasing everyone — a very fragile instability that’s like a snake eating its tail.

Thank God for our ai future: “ Unfounded fabrication is the act of creating or presenting false information, such as data, results, or evidence”.

I don’t get why the fed is so afraid of a recession when they have ample room to cut….

Why not keep rates high until there’s some actual weakness then cut to prop up the job market. This attempt at a soft landing just keeps resulting in more inflation because they’re terrified of a recession

Also long term this will result in higher interest long term interest rates to fund our spending if the US doesn’t get inflation under control and the rest of world does.

It also adds to the argument of not using the USD as the sole world reserve currency.

The reality is this is not the 1950-80s. The Fed does not have same power it once did. Government can and does undermine the Fed by issuing insane amounts of short-term debt and reinvesting in the economy.

Once they bailed out SVB, everyone knew the party was going to go on forever. I’m not saying they had a choice. SVB had to be bailed out (yes I know the shareholders were wiped out but depositors were made whole). The point is, the party can go on forever and the end game is another round of massive QE. How? you force the Fed’s hand. Party like no tomorrow, eventually shit breaks. Fed will come to the rescue because they don’t want damage to spread in the financial system.

If Trump wins, bitcoin becomes a strategic asset for the US. You can bet that because of how deeply he and his family are involved in this asset class. Bad situation gets worse for the Fed.

They will eventually become like bank of Japan.

that isn’t having the party go on forever. that is going until the currencies are destroyed, like all fiat currencies eventually are.

How does the Fed buying bonds help Bitcoin?

I should have worded that differently:

Why would Bitcoin being a strategic US asset cause problems for the Fed / force them to buy bonds? At least that’s now I’m interpreting your last two paragraphs.

>SVB had to be bailed out (yes I know the shareholders were wiped out but depositors were made whole).

SVB (or rather, their idiotic uninsured depositors) absolutely did not have to be bailed out.

Like QE, this was a choice. Like QE, this was an *incredibly bad* choice.

At that moment, markets saw the terror in the Fed’s eyes and the orderly unwinding of the insane pandemic bubbles stopped and reversed.

agree. they saw that the fed was not willing to accept any real pain outside of a very limited scope, and acted accordingly.

What if? I’ll just keep doing the same thing. Working hard at work, saving, being thrifty, spending mainly on essentials/not much discretionary, eating inexpensive, healthy food at home, try to eat less unhealthy snacks, trying to keep current transportation in good running condition, not buying bubble stocks or real estate, try to give more to the homeless and charity, remind self through reading of the good books that the rewards of the hereafter are much more than the material wealth of this life.

I’m right there with you on eating at home, and keeping my (13 year old) car in good running condition.

Thanks, better tomorrow. I was with you until the last sentence. If the rewards in the hereafter we’re truly greater than life here on the earth, we’d all off ourselves rather than go to work every Monday. Deep down, I guess we don’t really believe the afterlife is better.

Thank y’all for the replies. Well, I know this site doesn’t get too much into that subject, so, just to keep it simple, the “good books” say we’re here for a purpose and a price was/is paid to sustain us, and of course, it’s terribly sad for families to lose loved ones too soon. Ok, thanks for entertaining non-business thoughts.

“The current situation also suggests that higher rates may actually be good for the overall economy,”-Wolf

They are certainly good for me. I can always use an extra $50,000 a year for doing nothing.

The current effective Fed Funds rate is 4.83%. The average annual rate since 1970 was 4.90%. If you eliminate the insane ZIRP years, the average 1970 to 2008 was 6.45%. So historically speaking, the current rate is not high. It is a little below average, and way below the 1970 to 2008 average, when the economy was humming along. Of course there were bumps and jumps along the way (variation), but I like averages. Don’t drink the Wall Street kool-aid. You can see what it just did to Chairman Powell. It made him look like an idiot.

“If you eliminate the insane ZIRP years, the average 1970 to 2008 was 6.45%. So historically speaking, the current rate is not high.”

But that period encompases the spike in yields in the early 80s, which was also a historical outlier.

Of course, if you leave out the datapoints you don’t like, you can get whatever you want. The government and MSM do this all the time. The 1970-2023 average includes ZIRP lows and the early 1980s highs.

The median helps to minimize variance:

1970-2023 average: 4.90%

1970-2023 median: 4.97%

1970-2008 average (excludes ZIRP years): 6.45%

1970-2008 median (excludes ZIRP years): 5.69%

All above the 4.83% current rate. Based on historical data 4.90% is “normal”. Note the definition of norm is “average”.

So, the recession indicator (Sahm) sounds ‘Danger, danger!’ and the powers that should not be tell her to say it was a false alarm. ‘Stay in your seats. There is no fire! Continue watching the movie.’ What a way to tarnish the credibility of your recession indicator. Well, it works most of the time! Right.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/claudia-sahm-says-her-namesake-recession-indicator-may-have-been-a-false-alarm-this-time-990f8dac?mod=bulletin_ribbon

People like you have had a really hard time for the past 2.5 years grappling with the fact that the US is not in a recession? Why is this so tough to deal with? Sahm said about the “Sahm’s Rule” what I have been saying about the inverted yield curve for two years: It has proven to be an unreliable indicator. Since 2008, the yield curve has been a reflection of the Fed’s balance sheet more than the economy. Over the past 25 years, the yield curve gave 2 false positives (indicating a recession when there was none, in 1998 and 2019) and 2 correct ones. That’s 50-50, luck of the draw.

Look, no matter how much you wish it, there is no recession in sight, the economy is growing faster than before the pandemic. But you people are coming up with conspiracy theories to tell us that we are actually in a recession anyway, it’s just being covered up somehow 🤣

There are no reliable rules, laws, or indicators in economics. Even the “law” of supply and demand does not work sometimes, although it usually works. Economics is not a science like physics or chemistry, although some economists like to think it is. There is nothing universal like e=mc^2 or Planck’s constant in economics. Economics has to abide by mathematical laws, but that is mathematics, not economics. (My favorite mathematical law is the law of identity: for all x, x=x.) However there is one very reliable indicator in economics. Economists will predict eight of the next four recessions.