The new supply: $138 billion of new 10-year Treasury notes replaced $66 billion of matured 10-year Treasury notes.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

This week, the government sold $654 billion in Treasury securities spread over 9 auctions, including 10-year Treasury notes and 30-year Treasury bonds.

Of these auction sales, $500 billion were Treasury bills with maturities from 4 weeks to 26 weeks, most of them to replace maturing T-bills.

| Type | Auction date | Billion $ | Auction yield |

| Bills 6-week | Jan-13 | 77.5 | 3.585% |

| Bills 13-week | Jan-12 | 88.8 | 3.570% |

| Bills 17-week | Jan-14 | 69.2 | 3.560% |

| Bills 26-week | Jan-12 | 79.5 | 3.580% |

| Bills 4-week | Jan-15 | 95.3 | 3.595% |

| Bills 8-week | Jan-15 | 90.3 | 3.600% |

| Bills | 500.5 |

And of these $654 billion in auction sales, $154 billion were notes and bonds, including $50 billion in 10-year Treasury notes:

| Notes & Bonds | Auction date | Billion $ | Auction yield |

| Notes 3-year | Jan-12 | 74.9 | 3.609% |

| Notes 10-year | Jan-12 | 50.4 | 4.173% |

| Bonds 30-year | Jan-13 | 28.4 | 4.825% |

| Notes & bonds | 153.6 |

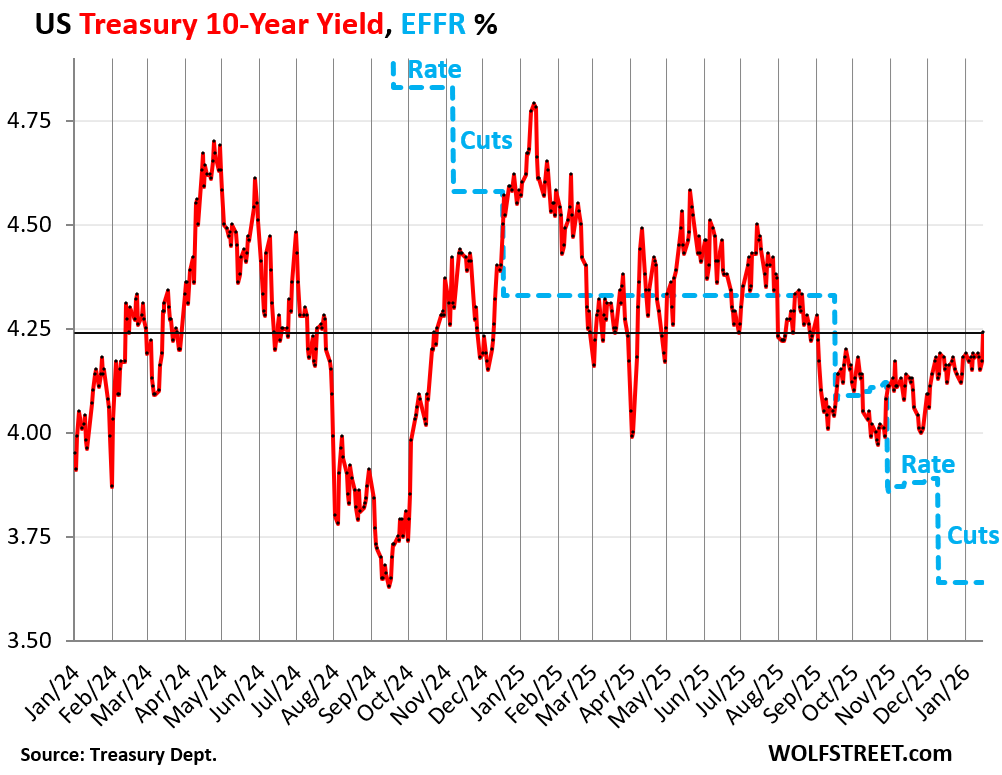

After the 10-year Treasury note sale on Monday at a yield of 4.17%, the 10-year Treasury yield then declined in the secondary market on Tuesday and Wednesday. But on Thursday, yields started taking off again and on Friday jumped to 4.24%, according to Treasury Department data, the highest 10-year Treasury yield since September 2, 2025 – which was three Fed rate cuts ago.

The Fed’s rate cuts have pushed down short-term yields, such as the yields at the T-bill auctions, but long-term yields are set by the bond market and reflect the bond market’s concerns, views, and fears about future inflation, future supply of Treasuries to fund the ballooning deficits, and all kinds of other concerns.

So the Fed cut by 75 basis points, and the bond market just blew it off, steeped in its own concerns (blue line = Effective Federal Funds Rate, or EFFR, which the Fed targets with its policy rates):

The 10-Year Treasury issue: $138 billion replaced $66 billion.

The 10-year Treasury auction this week was the third auction (the second “reopening” auction) in a series of three auctions of the same security with CUSIP number 91282CPJ4, all with the same coupon interest rate (4.0%), and the same maturity date (November 2035). The “yield” was established at each auction via the price.

At the January 12 auction, these 10-year notes were sold at a price of $986.07 per $1,000 of face value, and buyers had to pay $6.74 for two months of accrued interest per $1,000 of face value, giving these notes a yield of 4.173%.

The first auction of this CUSIP issue was held on November 12, 2025. Then this issue was reopened at the December auction when a fresh portion of the security (same CUSIP, same coupon interest, same maturity date) was sold. This week, another fresh portion of the security was sold. Each time, the yield was established at the auction via the price. At the original auction on November 12, 2025, these securities were sold at a price of $993.97 per $1,000 of face value, giving them a yield of 4.074%.

Grouping three months of auctions into one security with the same CUSIP, same coupon interest, and same maturity date – rather than having three different securities – increases the liquidity for trading in the secondary market.

The total issue for this security, all three auctions combined, amounts to $138 billion. The next 10-year note auction on February 11 will start a new cycle of three auctions of securities with a new CUSIP number.

Those $138 billion in securities sold over those three auctions in November, December, and January replaced $66 billion of 10-year notes sold in November and December 2015 and January 2016, with a coupon interest of 2.25%, that matured in November 2025 (CUSIP number 912828M56).

That’s how the amount of 10-year Treasury notes outstanding increases each month, even if the auction size going forward isn’t increased from the current size.

And interest payments will nearly quadruple. The new security (CUSIP 91282CPJ4) was issued with a coupon interest rate of 4.0%. The matured security (CUSIP 912828M56) was issued in 2015 and 2016 with a coupon interest rate of 2.25%.

That math is brutal: Going from $66 billion borrowed 10 years ago at 2.25%, and interest payments of about $1.48 billion per year; to $138 billion borrowed now at 4.0%, and interest payments of about $5.52 billion per year. The interest payments will quadruple!

Shift to T-bills or just jawboning to push down long-term yields?

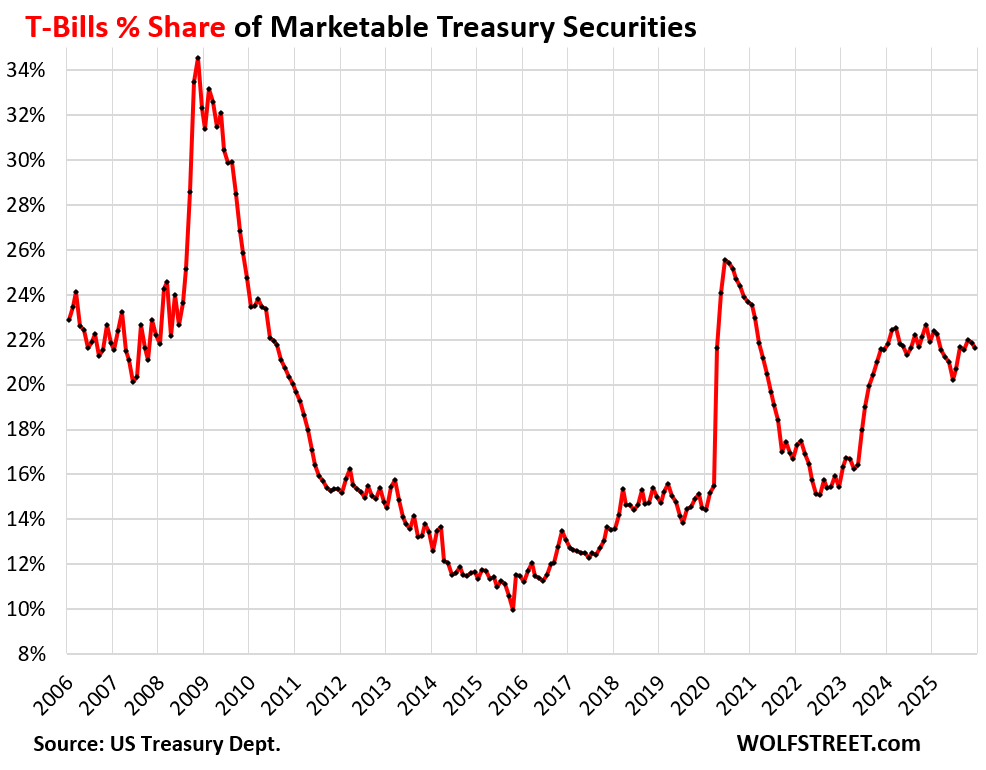

T-bills outstanding at the end of December dipped to $6.55 trillion, after setting a record at the end of November.

The share of T-bills dipped to 21.6% of all marketable Treasury securities outstanding, exactly where it had been in December 2023.

All this talk by Bessent’s Treasury Department about shifting more issuance to T-bills was one of the many tools with which it attempted to jawbone down long-term Treasury yields. But the shift hasn’t actually occurred yet.

Why? Because total marketable Treasury securities ballooned by nearly the same rate as T-bills ballooned since December 2023: +14.8% for total marketable securities versus +15.4% for T-bills.

The amounts of notes and bonds outstanding ballooned via the mechanism described above with the example of the 10-year notes, where a new issue of $138 billion replaced a maturing issue of $66 billion.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

For a long time some doom and gloom types have said our debt is unsustainable and disaster is ahead. But if there is a strong demand for U.S. treasuries then that won’t happen right?

There will always be enough demand for Treasury securities if the yield is high enough. That’s how yield works.

The question should be this: what will the yield be in the future to create enough demand? For the 10-year: 5%? 6%? Every time the 10-year yield approached 5%, demand exploded and pushed the yield back down.

Can the U.S. experience a sovereign debt crisis? Our government is acting very belligerent against other countries. Even our long term allies. I am afraid this is going to change how other countries and people do business with the U.S. If the world boycotted the U.S. and our treasury bonds then what would happen?

A country cannot have a sovereign debt crisis in debt that it issued in its own currency. Even Argentina never defaulted on its peso debt; it only defaulted on its USD-denominated debt. Greece defaulted because it doesn’t control the euro and cannot print euros. The US doesn’t issue debt in foreign currency.

There may be some kind of crisis, such as inflation taking off, or something else, but not a sovereign debt crisis.

Wolf,

I’m glad that you gave Nimesh an answer because…

“There will always be enough demand for Treasury securities if the yield is high enough.”

1) Which is true *but*

2) To keep market-clearing Treasury interest rates from exploding to “harmful/destructive/apocalyptic” levels,

3) The Fed may “step in” (cough, cough, ZIRP) to buy at those Treasury auctions at *lower* than free-market-clearing interest rates.

4) But

5) The Fed isn’t a magical diamond pooping unicorn

6) It comes up with the “money” to buy into Treasury auctions by,

7) Simply “printing it” – unbacked by any proportionate increase in supporting real world assets.

8) So the ratio of “money-to-real-existing-assets” declines – which is the definition of inflation.

9) That “inflation” may be “latent” (sort of wrapped up in Fed-bank reserve relationships), asset-based (PE ratios go to 30 from 15 or your apt rent goes up 20% or…), or “traditional” (ground beef goes to $7 per pound from $4).

10) Basically, there is no free lunch (in fact, likely the price of lunch goes up, with everything else…)

11) But the Fed/Treasury powers-that-be, feel that the damage wrough by actual/latent/possible inflation is less than that of having Treasury interest rates (and every other interest rate in the world keyed off them…which is basically all interest rates) go from 5% to 10% (or 15% or 20%…) in a true “free market” setting.

12) And behind *that* powers-that-be-decision are 60+ years of fiscal deficit powers-that-be-decisions that felt that *whatever* government spending priorities that occurred…they were more important than confining them to the actual tax revenues available at the time. (Failed wars and day care frauds included)

Argh…point #8 should read,

“So the ratio of “money-to-real-existing-assets” *increases*…

To Wolf’s point, I could see a significant upsurge in inflation or a return of bond vigilante-ism as possible crisis situations in the coming years, since both the Federal government and central bank are looking reckless.

I believe many consumers in Canada, the EU and other parts of the World are flexing their muscle and beginning to boycott American companies. It’s a powerful tool. You can thank this administration.

With the gigantic trade deficit that the US has with these countries, I would be more worried about US consumers boycotting their products. How may US-made cars are Germans buying?

How much debt this negative cash flow operation will pile on, who can guess? But there is little question that the lack of the guardrail is the weakness of our democracy. When “kneidel day” comes, the US will have a broad population of very hard working people, our political system will look very different, and the public will understand a bit more about economics.

Wolf – what about Russia in 1998? They defaulted on ruble-denominated debt due to poor fiscal management and lack of investor confidence. Couldn’t print more currency without risking hyperinflation.

I’m confused by your comment of countries not being able to default on debt denominated in their own currency.

Nimesh,

I think at least two types of “gloom and doom” people exist. Those who look at their personal situation and squeeze longer historical trends into their time window. The 2nd type I wouldn’t even call gloom and doom that recognize certain data points that indicate current debt level is unsustainable and while that in itself matters little it is the impacts that lead to lower quality of life for the majority of Americans. It is possible the US figures out how to solve the significant amount of issues that it faces but I think reasonable to state the US is facing an unprecedented times. Whether that is 20 years, 50 years, or longer, the future is not written, but without a change in trajectory it doesn’t look good. If you call that doom and gloom, so be it, but it also fits the decline of empires narrative very well. More imperialism might work for a bit but hard to see that working long-term in a multipolar world. But of course theoretically the people can simply vote differently and choose priorities our democratically elected officials will implement. Hard not to end with a little sarcasm!

There is no such thing as unsustainable debt levels.

As long as there is demand for ust no problem.

Also us gov can never default.

Even with 38 trillion dollar us gov debt the 10y yield is well below 5 percent.

Jon,

Your idea of debt always being sustainable assumes the same old American hegemonic model. As is always said here, yes the US can’t default and yield solves all demand issues, but that hardly implies stability over the long term and certainly means that without changes the quality of life for Americans collectively goes down. Can you name some positive trends that buck most current trends? I suppose one could point to tariffs income and government funding industry but in my mind it isn’t clear either will deliver as promised. Shrinking the US trade deficit could be considered a good thing although I think it is comical think it should be balanced but a declining trade deficit or increased tariffs don’t necessarily translate into better quality of life.

Ironically, imo, if we got rid of all the cold war thinkers in government, there are a lot of solutions out there. Human nature is not one thing but just old mental maps that don’t work today, but very difficult to confront as well. Recycling the Monroe Doctrine/manifest destiny is tired and irrelevant. It was good at the time to tell Europeans to stay away but beyond that simply a framework of oppression. We should be on a apology tour not colonialism/imperialism 2.0 tour.

This is the MMT fiction, which ignores the Fed role in artificially restraining interest rate levels and the destructive inflation that results.

Even slippery academic MMT practitioners – when cornered – admit that *inflationary* crises can occur due to MMT, if not “default crises”.

But if the US macro-economy gets ruined as a result of MMT word games- who gives a sh*t about the label?

A 38 trillion dollar debt effectively limits fiscal policy response to economic crises, leaving only monetry response. And I am reminded of what Nixon did when inflation soared and fiscal solutions were not available. He instituted wage price controls. That didn’t work out too well.

Glen- Even with the outdated thinking, agreements are already in place….. Trump loves his power fantasies….

A decades-old Cold War pact already gives the United States plenty of room to operate on the island, including permission to “construct, install, maintain, and operate” military bases, “house personnel” and “control landings, takeoffs, anchorages, moorings, movements, and operation of ships, aircraft, and waterborne craft.”

“Everything that this current administration wants to do, they can already do it,” according to Romain Chuffart, managing director at the Washington, D.C.-based Arctic Institute think tank.

Have you ever seen the movie Idiocracy?

The problem is most of population isn’t financially literate so they’re gonna vote for whoever sounds like will make their life easier.

Inflation increases the wealth divide and long term destroys nations.

Also just watched an interesting video with Trump’s son talking about how he used to be able to get a loan for any real estate deal he wanted but how after his Dad’s presidency (really after January 5th) none of the big banks would do business with them. This video theorized that’s why the Trump family got into crypto, when during his prior term Trump called crypto stupid.

My thought is maybe now he wants to destroy the currency? He knows that inflation is why the Democrats lost the election. People hate inflation. I can’t think of any logical reason for his actions.

I mean even the Republicans are against messing with the Fed.

And whatever the official numbers are, to me and everyone I talk to, still feels like prices are going up in a lot of categories… grocery shopped today and could provide a long list of things that are up far more than 2% in the last 6 months. My gym membership just went up 4%. A prescription drug I need to take daily jumped from $25 to $62 thanks to a change in pharmacy benefits despite keeping the same health insurance which also went up in cost for both me and my employer. Gas is cheaper though I guess.

Yes if nothing bad happens then nothing bad happens. Checkmate, doomers!

A 737 crash only kills everyone on board due to the fall of the last foot, not the 34,999 foot fall that preceded it, right?

So, if the plane is plummeting, no correction is needed until the last foot, right?

I rarely criticize someone else’s comment, but that’s a stupid, pathetic analogy.

“Ace”-

A weak mind would fail to see it’s just a time compression analogy……sooner or later all things seem to end. In human context it’s all about who is there when they do.

We COULD try to slow the planet killing for our species…..or not.

The constant mantra is that these current rates are too high and restrictive.

Restricting what, exactly?

These rates are in the historically normal range.

We just had a HISTORIC inflation………is that logically followed by historically normal rates? No.

The pressure is upward and the Fed resists and attempts to control the perception of what rates should be.

The reasons for the last rate cut evaporated. GDP 4.5%, Unemployment 4.4%.

The point to track is the auction results of the ten year. When the subscribers go under water, as noted, people begin to move to the edge of their seat.

What does the Fed do when their narrative detaches from the realities of economics?

They’re too rate to maintain ever increasing prices of houses and stonks. That’s all the media cares about.

I agree that the current monetary policy is definitely of a monetarist bent regardless of the mathematical evidence that the current policy is probably the single most likely cause of the inexcusable asset price bubbles.

I haven’t checked for a while what Fed interest rate would be suggested by the Stanford professor that recommended that monetary policy, in the face of an inflationary environment should be set at least 2 pct above the most trusted report

Inflation is an economic cancer

If physical gold trades in a free and open market, is its price not a real price signal? Is this signal not saying owning any fiat currency like the DOLLAR, or owning the currency through owning US Government Bonds, is a poor choice or alternative? The gold market price increases basically suggest investors prefer gold over bonds? Thr investors in gold receive no interest on their investment.

A ten year Treasury at 4.17% today is the market saying I need this yield in nominal interest rate to pay be for the ——% expected inflation and the ———% real yield .

There are huge liquid deep and broad market of players here setting bond prices and thus nominal bond yields.

Many investors must stay in the bond market for the cash flows and cannot move over to gold market. All the gold investors/players could be in the bond market.

The gold investors must be saying that the the nominal yields all across the treasury curve are too low to protect there buying power.

Are these market signals contradictory or consistent?

/

1. Last line first: “…must be saying that the nominal yields all across the treasury curve are too low to protect their buying power.”

Agreed. Especially with the longer-term notes and bonds.

2. “owning any fiat currency like the DOLLAR, or owning the currency through owning US Government Bonds”

You don’t own “dollars.” You cannot own dollars. It’s impossible. Just like you cannot own “miles.” But you can own assets denominated in some currency, such as dollars. But you can denominate stocks or houses or oil, gold, anything in any currency. You don’t own the currency; you own the asset denominated in that currency. You can sell your house and get paid in euros for it, if you like. You own the house, not the currency. Same with all assets.

Even the paper dollars in our pocket are an asset, a loan you made interest free to the Federal Reserve, which is why they’re called Federal Reserve Notes.

The problem with “fixed income” assets – such as Treasuries – is that the income is fixed. If you buy at auction and hold to maturity, you get the interest payments along the way and face value at maturity, no capital gains. So if you buy at auction and hold to maturity, there is no real way to earn capital gains. On the other hand, your principal is not at risk. But in an inflationary environment, it’s the capital gains that you hope will beat inflation, but there are no capital gains…

Now you could buy some beaten up junk bonds for 30 cents on the dollar, and if lucky, the company survives till maturity, and then you get 100% of face value, plus the high interest payments along the way. But that type of investment is not for the squeamish.

3. “If physical gold trades in a free and open market, is its price not a real price signal?”

No. Look at a 50-year gold chart: Huge spikes followed by big plunges. So not a price signal of anything.

Gold is an asset that over the very long-term beats inflation handily but in between is subject to massive manias and to plunges when the manias deflate. The last mania began deflating in late 2011, and the price of gold then plunged by 50%. Neither the mania nor the plunge was a price signal of anything.

It’s perfectly good to trade gold to profit from short-term moves, and it’s perfectly good to hold gold for the very long term and not worry about price movements, and let your heirs worry about what to do with it. But it’s nonsensical to shove some big meaning into these price movements when the price of gold soars, but then when the price of gold plunges, there is suddenly no meaning?

“and let your heirs worry about what to do with it. ”

That was one of the main reasons I have in hand gold and silver,short of true emergency goes to loved ones,price drops will stack more.

In my giant folder of research PDFs that I have accumulated in lieu of getting a girlfriend, there’s a paper on this called “The Gold Dilemma” from 2020, which gets into the weeds on the different theories about what gold is actually worth and why the price is so high. The conclusion:

“…We find little evidence that gold has been an effective hedge against unexpected inflation whether measured in the short term or the long term. The ‘gold as a currency hedge’ argument does not seem to be supported by the data. The fluctuations in the real price of gold are much greater than FX changes. We suggest that the argument that gold is attractive when real returns on other assets are low is problematic. Low real yields, say on TIPS, do not mechanically cause the real price of gold to be high. While there is possibly some rational or behavioral economic force, perhaps a fear of inflation, influencing variation in both TIPS yields and the real price of gold, the impact may be more statistically apparent than real.

…We also parse the safe-haven argument and come up empty-handed. We examine data on hyperinflations in both major and minor countries and find it is certainly possible for the purchasing power of gold to decline substantially during a highly inflationary period. When the price of gold is high in one country it is probably high in other countries. Keynes pointed out ‘that the long run is a misleading guide to current affairs’. Even if gold is a ‘golden constant’ in the long run, it does not have to be a ‘golden constant’ in the short run. Conversely, current affairs are possibly a misleading guide to the long run…”

“Is that a giant research folder of PDFs, or are you just happy to see me?”

Hmmmmm….,between me gold and silver(in hand)I am at moment on Asian markets up almost 10 thou in fiat,will keep it.

That’s one of the reasons I trade gold and silver and dont keep it long term along with stocks .

Paying the 2% to 5% spread between buying and selling gold is pretty expensive transaction.

If your buying GLD or SLV, you not buying the PM, your just buying a paper contract.

“You don’t own “dollars.” You cannot own dollars. It’s impossible.”

“You don’t truly own anything you can’t carry at a dead run.” – Heinlein

In the long run, to paraphrase Keynes, we are all dead, which means we don’t own anything for very long. We are all renters.

That’s what I thought until the chaos of a bubble unwinding back in 2006.

Well firstly physical gold, although dense, is difficult to securely maintain without a security team to guard the gold stash that often happens they, the security team, conspires to steal the gold.

Inflation is more pervasive than Trump thinks.

That’s an understatement. Saying that “inflation is done” after it accelerated for most of 2025 was not a bright move and not well received by almost anyone. I believe Harris was mostly sunk by inflation and Trump is tripping acid if he thinks the same can’t befall him.

Latest estimate: 5.3 percent — January 14, 2026 GDPnow just ticked up.

Economy is stronger than forecast.

GDPNow is getting confused again, like in Q1. Back then, imports of monetary gold blew up GDPNow, and the Atlanta Fed then created a new GDPNow algo to account for gold imports correctly. But now the same thing is happening with gold exports; I don’t think they’re accounted for correctly. So when the actual GDP figure is released for Q4 by the BEA, it will be a lot lower than GDPNow. It will probably still be pretty good though, maybe 3%?

That looks lik Chinese growth figures…

Wow, Donny did it (sarcasm)

Trump’s Greenland tariff squeeze detonates Europe trade deal as NATO is pushed to breaking point

The European Union warned it will block a trade deal with the US after President Donald Trumppromised tariffson eight countries supporting Greenland. President of the European People’s Party Manfred Weber, the European Parliament’s largest political group, said on Saturday that an agreement with the US was no longer possible. The agreement, struck last summer between Trump and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, has been brought in but still requires a rubber stamp from the parliament.

the Danish ingrates oblivious of the subsidy that America has provided for all of these years. One would think that we have already paid for it many times over, perhaps.

I once knew a Danish couple that lived next door that I’m pretty sure caused me to lose my apartment because of their complaint.

The Danish are a lovely people.

Yes maybe, but please ..

We are in 2026. You cannot buy people.

Please keep Greenland and their people out of your calculations.

European under investments in Nato must be adressed in proper Capitals in Europe.

Not with random tarrifs

My brother in laws Dad was a Dane that moved to Solvang after WW2. he was part of the underground in WW2. As a bonus, he and his buddies were ‘allowed’ the box up insane wealth from vanished Jews and ship it to California where they began their new life. His house looked like a museum of stolen Jewish wealth. It really began to boom circa 1947 with the spoils of war.

The Danes apparently aren’t(for good reason) that popular with Greenland’s native population. They just want independence but I don’t see that happening.

If you hate everyone Fox News tells you to, you won’t be able to keep up.

Kudos for trying tho

Our cow stopped giving milk because this old lady gave it a dirty look.

But then we got her on the ducking stool and she fessed up.

Alternate comment: Jesus wept.

It’s a move worthy of the books if it works, and a big chunk of it is riding on the SC Tariff case.

If the NATO $pigot is turned off, Europe is faced with a dilemma – continue to finance their social programs or finance defense. Fail to finance the social, the unrest presented by immigrants will force nationalism. Fail to finance defense, well…. Zbig Brzezinski’s The Grand Chessboard lays out the facts. The ‘EU’ will fade. Greenland will come into US orbit.

We wait for the SC decision.

Reality checks:

Europe builds its own fighter plane: Euro Fighter.

When the US held a ‘bake off’ to pick its next tank: the German Panther exceeded the required specs…but which politician would dare order a German tank? The gun in the Abrams is by Reinnmetall, built in US under license. France has its own nukes as does UK, which is also sending force to Greenland.

Social programs? Yes they are expensive but at least they have the most important one: universal govt health coverage.

Their govts will be overthrown due to popular reaction to immigrants?

Transference.

Correction: German tank in competition was ‘Leopard’. Of course they wouldn’t enter one with name of WWII tank.

Maybe you got it right the first time around. The newest German tank is Rheinmetall’s KF51 Panther, which made its first appearance in 2022. There was also the WWII Panther you’re now alluding to. The Leopard II is a design dating back to the late 1970s.

In terms of the “bakeoff” that you mentioned, I have no idea which tank was involved in that.

Imagine next week yield will lift off and breakout after the tariffs to bend the knee if SCOTUS keeps on the sidelines. I never thought I would be witnessing these events in my lifetime. To bad our new best friends like EL Salvador, Hungary are not flush with money to buy our US debt. Canada met with China this past week to make better trade deals. It reminds me of the expression my enemies enemy are my friends.

These large budget deficits have not been addressed by either party. I see a bond market collapse in the next 6 months when there are not enough buyers at these auctions to absorb the large supply. The bond vigilantees are on the sidelines, salivating, waiting for the time to jump in an make a killing, while the housing market & economy collapses.

As Wolf has said, these bonds auctions will always continue to find buyers for the debt, the question is what interest rate will the increasing volume of bonds need to sell at to attract enough investors. Does the collapse you envision just mean an explosion of interest rates?

When you say bond vigilantes on the sidelines, are you referring to the investors waiting for rates to climb over 5% swooping in to buy? Those “vigilantes” are then the force preventing bond rates ballooning any further, thus being a helpful backstop of worse pain in the housing market. Plus, wouldn’t their surge of participation also contradict your prediction of an impending bond market collapse?

All that said, the budget deficits indeed remain an ongoing issue and both parties are absolutely complicit. It’s a bit hyperbolic to claim bond market collapse by July is all.

I found this interesting post from the Fed.

Nothing like top secret Cayman Islands entities having a huge influence on our debt market. Investors my ass!

“This note examines the magnitude and implications of potential underreporting of U.S. Treasuries owned by Cayman-domiciled hedge funds in the TIC data, which are the primary source of cross-border securities and banking data in the U.S.”

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-cross-border-trail-of-the-treasury-basis-trade-20251015.html

Those hedge funds ARE investors (institutional investors). They’re using Treasuries as basis to back the Treasury futures that they create and sell. The article by researchers at the Federal Reserve that you linked found that the Treasury Department in its Treasury International Capital (TIC) data does not account for $1 trillion of those Treasuries as being held in the Cayman Islands; instead they found that they’re still accounted for as being held in the US by those hedge funds which are US hedge funds with a legal address in the Cayman Islands.

The TIC data collection apparently doesn’t pick up on that, that’s what they said, in an effort to get the Treasury Department to fix their system so that it can correctly track the location of Treasuries held by US hedge funds at legal addresses in the Cayman Islands.

If those Treasuries were accounted for as those researchers want to as being in the Cayman Islands, instead of in the US where these hedge fund offices are located, it would shift $1 trillion of Treasury holdings from US institutional investors to the Cayman Islands.

I have not yet seen any response from the Treasury Department about this issue, but maybe I missed it.

Nor has the Treasury Department changed its tracking of those Treasuries, and in its most recent TIC data, those Treasuries are still not being counted as held in the Cayman Islands.

But this issue doesn’t change the size of the basis trade nor the size of hedge funds in the Treasury market. It’s just where the legal entities holding these Treasuries are located.

A certain school of thought believes that budget deficits don’t matter which is why we have gone from 5 T or so to 38 T in debt which has been issued to a select group of grifters

I wonder what role Palantir, a DOD suckling pig is playing in disrupting our democracy in MN

I’ve been hearing about the bond vigilantes for years. There is extremely low volatility in bonds right now, like they are just going to stay in a trading range for the foreseeable future.

Bonds had one of their worst years ever in 2022, thanks to the fed.

But what were the other options?

Now that opposite effect makes bond’s potential much better. Makes them more important as a ballast. And so they should earn more and more to equalize the 2022 loss.

The fed up until now has been patching up battle wounds so the economy doesn’t bleed out. Some folks in the big house have zero clue about economic theory. They are just peons in the order of things. So when they take the teeth out of the fed, no more patching up battle wounds. We prob will have longer and longer periods of bad economic times.

Rumour floating around that stablecoin buyers are actually buying US debt. Strange that this is not reported on – if it even matters. I know Wolf loves his crypto 😂

Count me in the gloom and doom camp. It just takes years to play out, perhaps decades and most of us count on being dead when the bill comes due.

It’s great that we can continue to borrow more and more and even borrow to pay the interest on our previous borrowing.

The logic seems to be that we can run 6% Fiscal deficits and trillion dollar trade deficits forever – all we have to do is keep importing foreign capital and the books will balance.

So why not 1.5 trillion dollar defense budgets. Why not offer every person living in Greenland 10 million to vote yes on becoming a US territory ? Social Security becoming pay as you go in 4 or 5 years….borrow and put it on the budget.

All things are possible with borrowed money and at very little cost today.

Delusion, give it time. I’m sure we’ll always have a bar stool next to Zimbabwe or la costra nostra!

Let me postulate a completely different scenario that calculates the free market valuation of the 10 year, without the Fed’s thumb on the scale, at 6.26 pct

All we need is love as the Lennon’s saw as the resolution to the world’s problems. As it turned out, pure fantasy worth billions.

All the while, underneath, are my favorites, the everyday people. The veteran community which receives an economic shock when they separate from the Armed Forces.

Mostly though it is every day people being subjected to the discipline of capitalism while being the most obvious victims

I’m not aware of any economic model that would suggest the current concentration of wealth as healthy, other than the current concentrated wealth

The most horrifying site on whole Internet, the most fearful site on whole Internet is, of course, Real Time USA Clock Debt.

The “Debt Clock” is just an algo designed to look like a slot machine to amuse the people. The numbers are obviously fake, wrong, and off massively. For entertainment purposes only.

The actual numbers of the US debt are published every day by the US Treasury department. The level of debt does NOT change every second. It goes up when new securities are issued, and it goes down when old securities mature and are redeemed. So on a day-to-day basis, the balance rises on some days and falls on other days. And on Saturday, Sunday, and holidays, there is no movement at all… but that’s not as much fun to watch as the Debt Clock slot machine joke that just keeps moving no matter what.

Actual US Treasury debt:

Debt on Jan 15: $38,453,108,492,348.67 (up from prior day)

Debt on Jan 14: $38,396,062,667,874.39 (down from prior day)

Debt on Jan 13: $38,433,852,753,680.03 (down from prior day)

Debt on Jan 12: $38,437,700,892,419.68 (up from Friday)

Debt on Jan 09: $38,433,330,126,292.37

Well thank you Wolf for giving me a temporary relief from the concept that the world is rapidly going to hell in a hand basket.

Personally, I think that the short term rates are not ideal but the long term seems to me to be miss priced in the sense that only a crazy cock eyed optimist would recklessly bet on the uncertain future for 4 pct.

I just read a Senator’s report claims there is $1.6T in fraud happening in the US.

Add to that the US defends all our allies at a cost of nearly $1T.

If we could address just these two issues we would be in pretty good shape.

We bring in 4.9t and spend 6.9T. I read 10% of our spend fraud recently too but I don’t believe it, I think doge would have found more waste and fraud if that number was even close to being true. We spend 1 T a year on our military, I look at that 1t as corporate welfare or a subsidy for the economy, historically the states have fought over jobs locations related to that money spend. South Dakota per capita may did ok if my memory is correct. Plus the military spend buys us the reserve currency or at has in the past. Smart people believe China is building up their military because they want the reserve currency in the future. How much money did Doge actually find in waste and fraud? Does anyone know the actual saving?

Senator who?? And based on what?

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Today, Chairman Rand Paul (R-KY) of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee released his 2025 “Festivus” Report, totaling $1,639,135,969,608 in government waste.

I guess he claims waste, which would include fraud and poorly designed and managed programs.

My bad.

In mid-2025, DOGE employee Sahil Lavingia sat for an interview and said he found “minimal amounts of fraud” and “a lot of waste”, and that some of the waste was due to bureaucratic rules in place to prevent fraud. He was immediately fired without explanation.

Federal laboratory workers are waiting a month or longer to have orders approved, and having some service contracts for equipment canceled, resulting in broken equipment and delays getting it repaired. This results in wasted time. Would it surprise you to know that this is happening due to rules put in place by DOGE? If so, I will say it bluntly: DOGE’s supposed efficiency changes are wasting your tax dollars, right now.

There is a political faction that has already decided that the government is rife with waste, fraud and abuse. They are administering solutions to solve problems that are nowhere near as widespread, and creating new problems that are worse.

It’s funny that Doge took over, made a bunch of fraud claims, nothing ever came of them, the US government is spending even more money, and that the same exact Doge people are now claiming that there is fraud again.

The people who fall for scams are the most likely to fall for scams.

Oh Rand Paul who got beat up by his lawn mower.

That guy is a strange bird man

Do we know who bought these treasuries? It would appear that China and Japan have lost their appetite for purchasing US debt and a reason why the interest rates are increasing. Did the Fed buy any (debt monetization)?

In terms of foreign buyers:

https://wolfstreet.com/2025/09/18/the-foreign-investors-who-bought-the-recklessly-ballooning-us-treasury-debt-and-why-theyre-so-important/

Here are all buyers, including US buyers – this is from June, but it hasn’t dramatically changed since then:

https://wolfstreet.com/2025/06/20/who-held-or-bought-the-huge-us-government-debt-even-as-the-fed-shed-treasury-securities-in-q1-shedding-light-on-this-iffy-situation/

Wolf,

Totalling these charts up sums to about $20 trillion (tried to avoid double counting).

With a $38 trillion debt…who holds the other “uncharted” $18 trillion?

(Perhaps “other countries” only means their *governments/CBs*- not the individuals and institutions under them?)

CLICK ON THE FUCKING LINKS

Is it just me or is that a lot of money?

Who’s counting?

Is there some way to normalize your plot of “US Treasury 10-Year Yield, EFFR%” to understand why it matters? If I look at the plot available from the St. Louis Fed “Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 10-Year Constant Maturity, Quoted on an Investment Basis (DGS10)” I see that the yield has been as high as ~16% (in September 1981). The world did not come to an end, but presumably conditions are different now, and the consequences would be more severe? In other words, it seems like we have a lot of runway and could go to ~16% based on history, and all would be fine and dandy.

Presumably the fact that the debt to GDP was also at an all-time low in 1981 (see “Gross Federal Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product (GFDGDPA188S)”) meant that the ~16% yield was not as big of a deal as it would be now, when the debt-to-GDP is essentially at an all-time high.

I was alive in 1981 (11 years old), and from my narrow perspective, nothing crazy was happening with a ~16% yield. So why should I care that it is at 4.25%?

“I was alive in 1981 (11 years old), and from my narrow perspective, nothing crazy was happening with a ~16% yield.”

Your whole perspective is distorted by what you remember or don’t remember from when you were 11 years old.

This was the period of the horrible Double Dip recession, with the unemployment rate eventually approaching 11%, tens of thousands of banks collapsed, hundreds of thousands of companies went bankrupt, jobs just vanished. The unemployment rate stayed over 7% until 1987 and didn’t drop below 5% until the late 1990s. I started my career in 1981, coming out of grad school, and for people starting out it was hell.

Thanks Wolf –

Well, put another way, all the bad stuff you describe when I was 11 in 1981, and was oblivious to–the threshold was 16% (for sake of argument). What is the threshold in 2026 for bad stuff to happen? I feel like it should be a lot lower than 16%, given metrics like the debt-to-GDP which are **a lot** worse. Is this intuition correct?

No it wasn’t hell dont you know the boomers had it easy lol

Thank you. The anti-boomer screeds drive me nuts. Never worked less than 50 (usually. 60 hours) per week until the mid 90’s. Same for most of the people I grew up with, except the top 2% of my class, who all became doctors, and lawyers and such.

To Stymie, here’s some perspective. I tried to buy my first house in 1981 but couldn’t/wouldn’t pull the trigger on those 17% mortgage interest rates, especially with the 8+% inflation also attacking our buying power. Worked two, sometimes three jobs, just to feed and house my new family, until 1996 as mentioned above,

Dumb question. The US won’t default on its debt because it controls its own currency, but purely hypothetical, how would this happen? If all foreign holders sold at once, the Treasury surely doesn’t have that much cash on hand, and can’t “print money”, so how would they be paid?

Such sales, before term, would occur on the secondary market and be to private parties once an agreed price had been reached. The US Treasury is not involved and is not obligated to pay back principal before term.

However, the agreed price is the issue.

Dumping huge quantities of UST on the secondary market would collapse the price and so skyrocket the yield. It would be stupid for the holders of UST to do this. Their return after sale would be pennies on the dollar

OK, thank you. Yes, it would be economic suicide, so I’m not really worried about it, just still trying to figure out all the mechanics of Government finance and the Bond market, since my retirement income will partially rely on it, and it does seem on an unsustainable path.

Willy K

That hypothetical is just silly. You can drive yourself nuts with silly scenarios like that.

1. Foreigners will never sell all once their Treasuries. SOME foreigners might sell SOME of their Treasuries. And they’re doing it. But overall foreign holdings have continued to rise and hit a new record in the most recent month. They have to do something with the dollars that they get from trade with the US.

2. If foreigners sell, it’s not the US Treasury that buys them, but other investors. It’s just part of the Treasury trading in the secondary market, the largest most liquid bond market in the world.

OK thanks, love the website, learn stuff every time I’m on here.

WORTH REPEATING

“So the Fed cut by 75 basis points, and the bond market just blew it off…”

“That math is brutal: Going from $66 billion borrowed 10 years ago at 2.25%, and interest payments of about $1.48 billion per year; to $138 billion borrowed now at 4.0%, and interest payments of about $5.52 billion per year. The interest payments will quadruple!”

Some other 10 year bond rates:

France: 3.35 %

Canada: 3.34 %

Germany: 2.847 %

could there be a “failed Treasury auction” akin to breaking the syndicate bid of an IPO?

People have been wishfully dreaming about “failed Treasury auctions” since the Neanderthals.

The German system allows for “failed auctions,” and they’re somewhat routine when the government doesn’t get the yield it wants. The Bundesbank then buys those bonds at the auction price and then sells them in bits and pieces to institutional investors or in the secondary market. It works just fine.

But the US auction system isn’t set up that way. Primary Dealers HAVE to buy all remaining bonds whether they want to or not, which is part of the deal in return for the privilege of being a primary dealer. They can lose that privilege if they don’t buy. They then sell those bonds in bits and pieces to their big clients, such as hedge funds or bond funds, or in the secondary market.

I am seeing that the primary dealers’ residuals have increased to 25 percent (some of them like Wells are at 30). Is this a signal that they are not able to do the offload that they plan to do in normal conditions?

Nah. They hang on to them for a variety of purposes. All banks have large holdings of Treasuries.

Bitcoin and crypto market are clueless and riderless on their own. The moment futures open down BTC falls 2k in the first hour than 1k in the second hour. $tnx closes above 42.72 equals rocket ship higher, $vix close above 18.52 she will run to 30. Nvda should be under crazy pressure tomorrow , Days after DJT said NVDA can export H200 chips and pay 25% fee China says no NVDA chips allowed. That’s a power play

If you are another country or large pension fund what else are you going to do with your money?

Ugly as America’s situation is, we still have folks willing to come here. Money also flows inward.

The U.S. consumer, our business is absolutely needed for a healthy free market. Americans love to spend. And other countries only benefit. Without American success, other countries cannot transact and therefore cannot grow GDP as well Americans do.

Not true, China is increasing its global exports as we buy less Chinese goods. We are ethnocentric here. The world doesn’t revolve around the USA I imagine we get hit with counter Tariffs Feb 1 than DJT hits back with more retaliation Tariffs, than the $tnx demand crashes from all the selling and maybe the usd with it. Perfect storm due to a childish reaction for not getting a shiny piece of medal. It’s going to be great to watch. Historically events and we are the bad guys to the rest of the world.

Wolf,

How much American debt do the EU countries own? I suspect that all the saber rattling about Greenland is simply a play to get Europe to buy more American debt and bring down yields.

Thoughts?

Check out the charts I posted yesterday in the comments further up for Treasury holdings by the Euro Area and the UK. For more details, click on the links in that comment.

Love going through the comments.

Thank you Wolf for publishing.

My belated comment after thinking about the increase in debt from the ’80s at $1 trillion to $38.5 is the quote from Hemingway’s novel.

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked …

Two ways: Gradually, and then suddenly,” a poignant line from the character Mike explaining how debts mount before a sudden collapse.

I think Dr. Copper, Professor Gold and Mr. Silver may be sending us a message.

“I think Dr. Copper, Professor Gold and Mr. Silver may be sending us a message.”

Yes, the message they’re sending is: “Total Mania Time.”

When gold plunged 50% and silver collapsed by 70% after the last mania ended in late 2011, they were “manipulated down by the big banks,” and when a new mania sets they’re “sending a message” about the collapse of the dollar? This stuff is just funny. Mania is mania, followed by hangover. Trade it to make money.

I disagree with Wolf on the “mania”. I’d argue it’s simply “repricing.” The same thing happened in the late 70’s.

Now I don’t want to bias anyone’s conclusions so do your own research and go look at what the DEBT/GDP was (using the old formula) and money supply. Also compare trade. Finally, we shut that repricing down by raising interest rates substantially. That is NOT and option now.

Wolf would argue that the dollar hasn’t lost any buying power. And there are no unwarranted hedonic adjustments in the published inflation numbers. So any increase in the fiat price of gold is a mania since no hedonic adjustments in a rock.

Yeah, there’s bank manipulation and bailouts. So this is a good thing?

As Einstein said: “Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world.”

The charges on debt are related to a cumulative figure; and since the multiplier effects of debt expansion on income, the ingredient from which the charges must inevitably be paid, is a non-cumulative figure, it would seem that the time will inevitably arrive when further debt expansion is no longer a practical or possible expedient, either to provide full employment or to keep debt charges with tolerable limits

Combined Domestic Nonfinancial Debt

Sector

Estimated Debt Outstanding (Q3 2025)

Government (Federal + State & Local)

≈ $36.9 trillion

Household

≈ $20.7 trillion

Nonfinancial Business

≈ $22.1 trillion

Total Domestic Nonfinancial Debt

≈ $79.7 trillion

So you’re saying if I print $100 in isolation and loan it to someone at 4%, they owe me $104. However, since there isn’t more than $100 in circulation, it’s not possible to pay back the debt with interest. So they can just pay back interest and borrow again and keep paying just interest? Until interest is more than the money in existence? Pretty much how I’ve seen the USD for quite a while now especially when I read “pay off the debt” when it’s not even possible due to interest and compounding. Even if all the deposits were seized out of everyone’s accounts. Which means they would have to seize physical assets…yikes…

Maybe it’s an EU bluff but something spooked the Bond market

yields estás en fuego

The 30 year Treasury just hit 4.92%. It is starting to get interesting again. The more Trump goofs arounds, the higher the yield goes. It’s almost like he wants higher long term yields, but keeps asking for lower long term yields. Is this five dimensional chess or insanity? It ‘s probably hard to tell the difference.