HELOC balances surged, mortgages not so much, and incomes grew a lot faster than housing debt.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

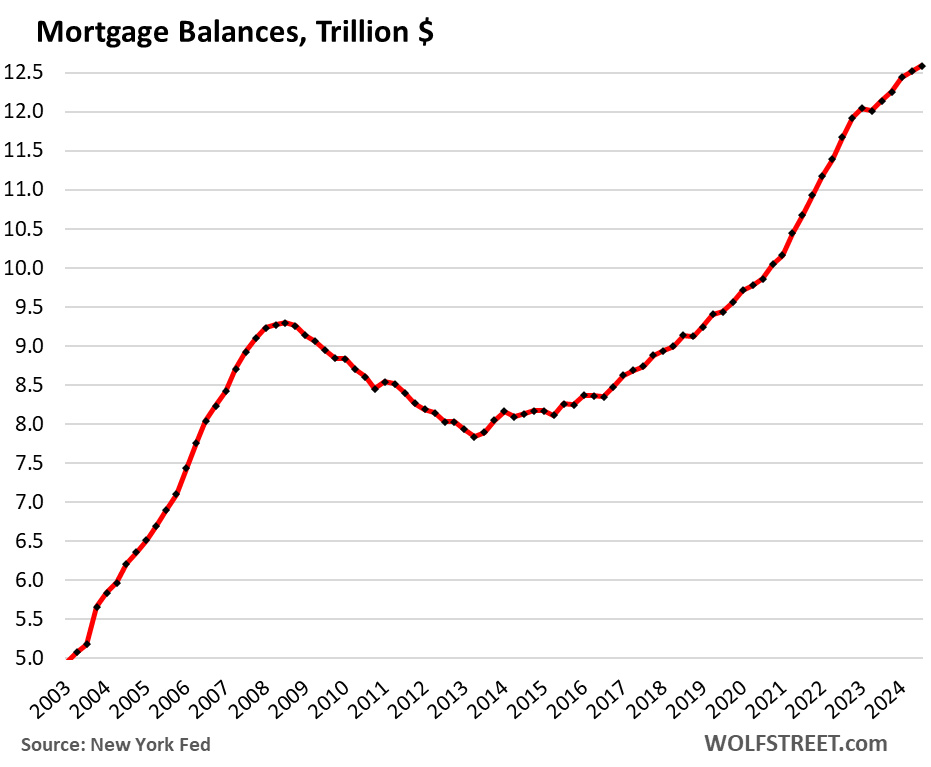

Mortgage balances rose by just $71 billion, or by 0.57% in Q3 from Q2, the smallest percentage increase since the dip in Q2 2023, and the second smallest since 2018, to $12.6 trillion, as demand for existing homes in Q3 plunged to the lowest since 1995, while more and more people who could buy are renting, thereby profiting from an arbitrage between two similar products with very different prices.

Year-over-year, mortgage balances rose 3.8%, according to the Household Debt and Credit Report from the New York Fed, based on Equifax credit reports. The increases over the years were driven by higher prices and thereby larger amounts financed, and peaked at 10% year-over-year during the frenzied Q1 2022 and were above 9% for the rest of 2022. But under the new regime of much higher mortgage rates and too-high prices that have either stalled or are falling, the increases in mortgage balances have slowed dramatically since the end of 2022.

HELOC balances surge.

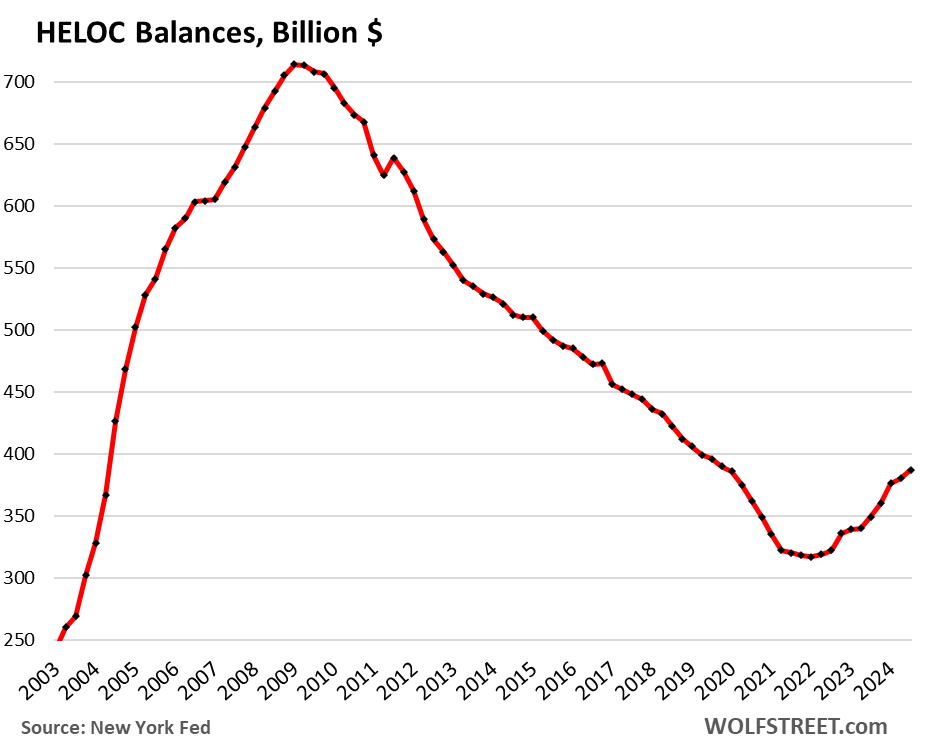

Balances of Home Equity Lines of Credit jumped by 1.8% in Q3 from Q2, and by 11.9% year-over-year, to $387 billion. Since the low point in Q1 2022, HELOC balances have surged by 22%.

Mortgage refinancings have collapsed due to the higher mortgage rates, and it makes financial sense in this regime, especially for smaller cash-out amounts, to get a HELOC instead of refinancing the whole mortgage plus the cash-out at a higher rate than the original mortgage.

Despite the surge, HELOC balances remain historically low after 13 years of incessant declines. Their share of total mortgage balances has now grown to 3.1%, from 2.8% at the low point. But back in 2005 through 2012, HELOCs amounted to 7-8% of mortgage balances.

HELOCs are a credit line, secured by the home, that homeowners can draw on to turn their home equity into useable cash. They come with interest rates that are generally 2 to 4 percentage points higher than purchase mortgage rates at that point in time – they run close to 10% now – but that’s a lot lower than credit card rates. And only the amount drawn against the credit line incurs interest.

Nearly half of all HELOCs recently originated had credit limits between $50,000 and $150,000, according to a separate report from the New York Fed. That’s the sweet spot for HELOCs. About 28% had credit limits below $50,000, and 25% had credit limits of $150,000 to $650,000. Only 1% had credit limits of over $650,000.

The burden of housing debt.

We’ve compared consumer debt levels to income for a good while now to see where this is going in terms of burden, sustainability, and risk, because we’re always worried about our Drunken Sailors, as we have come to call them lovingly and facetiously, because they’re such a crucial part in the economy.

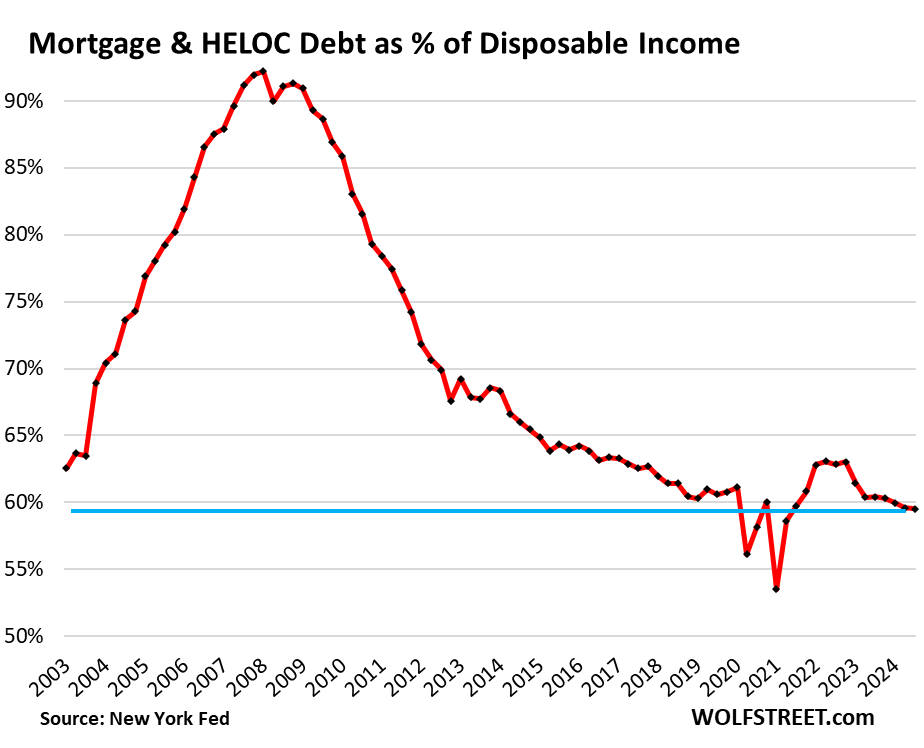

The income measure we use is “disposable income” from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. That’s after-tax wages plus income from interest, dividends, rentals, farm income, small business income, transfer payments from the government, etc., essentially the cash that consumers have available to spend, pay debt service, and save.

And for this purpose of determining the housing-debt burden, we look at mortgage debt and HELOC debt together – housing debts.

Total mortgage and HELOC debt rose by 0.60% in Q3 from Q2, to 13.0 trillion, and by 3.9% year-over-year.

Quarter-to-quarter, disposable income rose faster (+0.77%) than mortgage and HELOC balances (+0.60%), and so the debt-to-income ratio edged down to 59.5%, the lowest in the data except for the few quarters during the free-money-stimulus era when disposable income was grotesquely inflated.

Year-over-year, disposable income rose 1.6 percentage points faster than housing debt (5.5% vs. 3.9%) and the ratio fell by nearly 1 percentage point.

In the years before and during the housing bust, the housing debt-to-income ratio inflated to scary levels, and when it blew up, it triggered the mortgage crisis that contributed, along with a lot of other leveraged bets, to the near-collapse of the financial system. As consumers dug out of the debris, they deleveraged. And currently their debt burden is relatively low.

On top of the worry list in terms of debts are the federal government and businesses, not consumers.

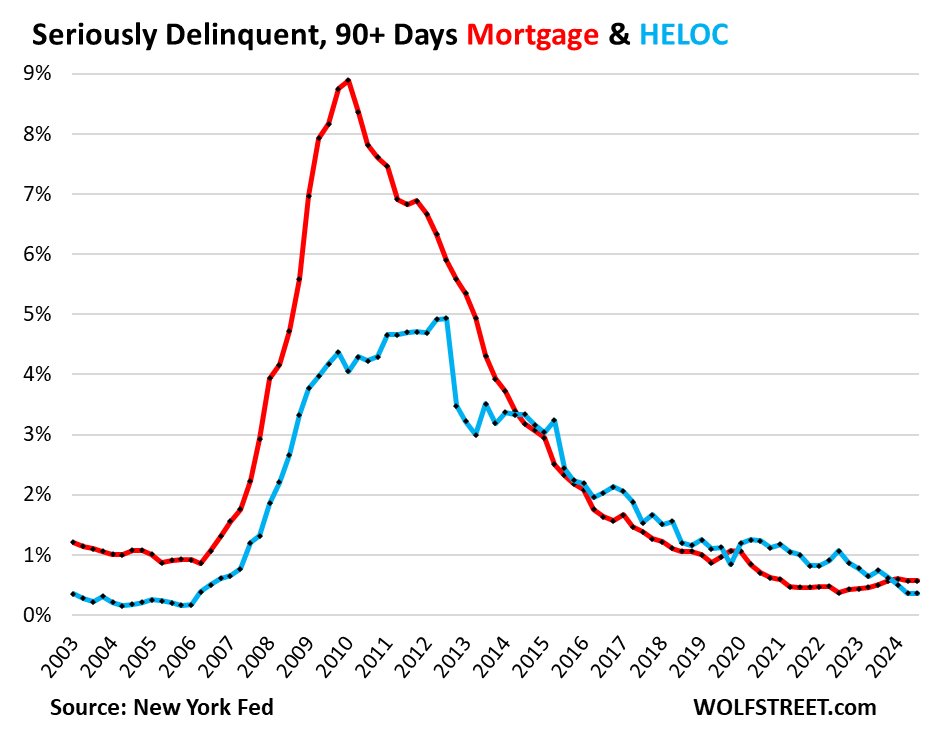

Serious delinquencies remain low.

Mortgage balances that were 90 days or more delinquent remained at 0.57%, well below the range during the Good Times right before the pandemic and before the Financial Crisis, both of around 1% (red line in the chart below).

HELOC balances that were 90 days or more delinquent remained at 0.36%, the lowest since 2006 (blue line).

After the 50% surge in home prices over the past three years, most homeowners, if they get in trouble, can just sell the home, pay off the mortgage and the HELOC, thereby cure the delinquency, and walk away with some cash.

Mortgages don’t get in serious trouble until home prices crater and people lose their jobs at the same time. When that happens, homeowners who can no longer make the mortgage payment cannot sell their homes for enough to pay off the mortgage. That happened during the Housing Bust when home prices plunged, and due to the Great Recession, unemployment spiked to 10%.

Even swooning home prices during a strong labor market don’t trigger a wave of mortgage defaults as homeowners will just quit looking at Zillow every day and continue making their payments.

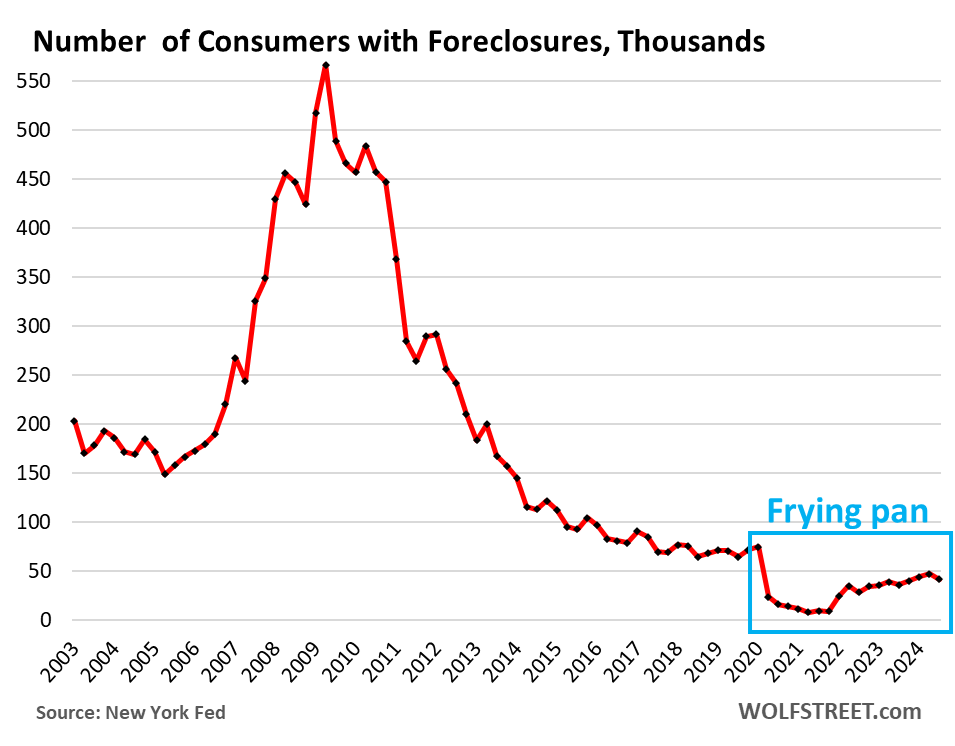

The frying-pan pattern of foreclosures.

The mortgage forbearance programs and foreclosure bans during the pandemic reduced the number of consumers with foreclosures to near zero. They have risen since then but remain well below the prior all-time lows, and in Q3 dipped further, to 41,520 consumers with foreclosures, down from 47,180 in Q2. In the Good Times right before the pandemic (2017-2019), there were between 65,000 to 90,000 consumers with foreclosures.

The post-pandemic frying-pan pattern, as we’ve come to call this phenomenon, has cropped up in other debt-problem data as well:

And in case you missed it yesterday: Household Debt, Delinquencies, Collections, Foreclosures, and Bankruptcies: Our Drunken Sailors and their Debts in Q3 2024

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Household debt continues to be a problem in North America. In Canada, where I live, the stimulus money provided by the Trudeau government was spent long ago. Living in the shadow of the American economy, the Canadian economy was hit hard by the crashing pillar of inflation that resounded from the East Coast of America, which is the center of the world economy. Debt has increased since then, as households strive to balance their greed for new material possessions with the obligation to repay all these outlays. Perhaps in the near-future debt will come under some kind of control if there is an expansion of the economy over a period of some years …

Canadian too. +Americans mortgage holders are safer than Canadians which are 5Y fixed & variable mainly. The refinance/purchase activity might be a bit “frozen” in the US but it mortgage holders are relatively financially healthy. Compared to US our home prices are astronomic, disposable income is way less (taxation) and we are more likely heading into an economic slowdown whilst the US is potentially going to accelerate out and have a no-landing scenario. Eventually we will benefit but it will be painful especially BoC has to do any emergency announcements. Their cuts are not sustainable relative to the US and our currency is under pressure.

Did you look at graph. It is lowest in history

By “North America,”* Dark Artist meant Canada, which is what he then discussed, and it’s a problem in Canada, for sure.

*In theory, “North America” is not just Canada, but also the US and Mexico.

Iws,

Did you accidentally microwave your brain this morning, instead of yesterday’s coffee? Mortgage balances were NEVER zero and will NEVER be zero. The lowest the data goes is $4.9 TRILLION. $4.9 TRILLION is not anywhere near $0. Even Musk’s wealth is not anywhere near $4.9 trillion. That’s more than the economy of Germany. But foreclosures were NEAR ZERO during the era or forbearance and foreclosure bans.

Go a step further: US GDP is $29 trillion in 2024, GDP in the US was NEVER $0, and it will NEVER be $0. Even before the Europeans came, there was an economy on the continent, and it was never $0, though no one knew how to measure it, or had the concept of dollars to measure it with. So you want to start GDP charts at $0?

Or a 10-year chart of the US population, which is now 333 million. You gonna start that at zero??? The population in this joint hasn’t been zero in at least 15,000 years. If you start that 10-year chart at zero, it will be a nearly straight horizontal line, and you can see nothing.

And then there are charts with negative values. So start those at zero too and cut off the negative values????

Charts are a magnifying glass held over the data so you can see the details. If the mortgage balances chart or population chart starts at zero, you cannot see any details, and the chart fails it purpose — that of a magnifying glass.

Only card-carrying idiots come here to clamor for charts to start at zero. All you did with this idiotic comment is earn yourself a permeant place of honor on my blacklist. Adios.

great option I haven’t done since mid-2000 to 2010

given ‘higher’ prices(not value)

I could use few hundred grand liquid

to go along with my own few hundred liquid

looking for more ‘pension’ properties

gonna need lots more income/assets that keep up devaluing fiat $dollar

This is a head scratcher here. I have sold four properties this year and three were full cash offers. We leveraged some of those returns as a short term loan to assist our daughter in buying a new house and carry over the equity from her previous.

These insights are based on a small sphere of vision in the Midwest, but would indicate an equally small effect on the numbers around amounts mortgaged this year.

The numbers miss the many cash or cash heavy offers of the extremely drunken sailors (Retired boomers drunk on massive market returns).

Things have slowed to more normal volume for this time of year while realtors are still abuzz about cash offers. Those that have the resources are still leveraging them to avoid these mortgage rates, for now.

All-cash purchases are included in the home-sales data. They’re not missed. They’ve been between 25% and 35% of total sales. In September, all-cash sales were 29% of total sales.

INCLUDING all-cash sales, home sales collapsed to the lowest levels since 1995. All sales figures cited include all-cash sales.

I agree, the inability of folks to differentiate between their needs and wants, although driving a consumer-fueled economy, creates so much accumulation of stuff and unnecessary debt.

Seems the solution to this entire housing economy problem is a deep recession and here we wait for the inevitable, but uncertain timing.

re: “According to its Balance Sheet Normalization Principles and Plans, the Fed will not abruptly shift between decreasing and increasing the size of its balance sheet from one month to the next.”

But that’s exactly what needs to be done to destroy inflation, to destroy inflation expectations, bitcoin, gold, etc.

An example: Some people think Feb 27, 2007, started across the ocean. “On Feb. 28, Bernanke told the House Budget Committee he could see no single factor that caused the market’s pullback a day earlier”.

In fact, it was home grown. There were “elephant tracks”. It was the seventh biggest one-day point drop ever for the Dow. On a percentage basis, the Dow lost about 3.3 percent – its biggest one-day percentage loss since March 2003.

What are the HELOC’s being spent on? According to Home Depot, Lowe’s, Floor and Decor it’s not home improvement projects. So where is the money going?

LOL, where do you think the $43 billion in Q2 revenues of HD came from? They were even up a little yoy. Do you think those $43 billion were grocery sales? Underwear sales? Nah, not HD. Lots of home improvements going on, just not quite as much as hoped. Before 2022, they financed them with cash-out refis. Now they finance them with HELOCs.

Savings, credit cards, cash out refis, then HELOCs. What comes next to finance the drunken sailors? Isn’t inflation blunting the spending spearhead? Of course, maybe its that I’m just not seeing this correctly. Wouldn’t be the first time. (A little grin from the Mrs.here.)

HELOCs are INSTEAD of cash-out refis, not in addition to. Cash-out refis have plunged for the reasons spelled out in the article.

Many use them for debt consolidation

Kevy Ray

No deduction for interest paid

Well, I just took out a small, $25,000 HELOC, to put new windows into my 98 year old home.

Smart. Save on energy and increase value of home. Ripping out a perfectly functional kitchen and putting in a new one simply to obtain a fresh look…not so smart.

I had a friend in my old neighborhood who bought a home in 2006 for $800k, immediately ripped out the doors and trim through out the house and reinstalled new trim to change the stain color, built a $100,000 bar in the basement with built in fridge and coolers, heated floors, etc., then sold it for $575k three years later. Bad investment combined with bad luck. His father in law wanted to kill him.

“Ripping out a perfectly functional kitchen and putting in a new one simply to obtain a fresh look”

I’ve never understood this either. What happened to “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” ??

I’ve purchased ‘upgrades’ for my house, but that’s different – not an investment by any measure.

Not at all trying to make you feel bad, but food for thought for anyone else reading:

When I did the Manual J (thermodynamics equation) on my previous (100+ yr. old home), I gathered that storm windows with the old windows would be nearly as efficient as new windows.

Old windows are part of the history of our beautiful old homes. Consider saving them, because you can’t get them back.

In the nearby (to my house) historic district, removing old windows is thankfully banned. My new neighborhood, (still over 100 years old) it is not yet, but it probably should be…

That “Seriously Delinquent 90+” chart seems reassuring with the rate now down close to half a percent…until you look at 2006 when it was similarly miniscule before exploding. I am certainly not saying the same thing will happen – but a jump to 2-4% from here would feel very disruptive. I continue to believe the only way out of this mess is for the Fed to swear off MBS forever and for houses to slowly and painfully trade hands at whatever price makes sense at that moment. Flat prices through 2030 might just be the best case for everyone. Buyers can save up and sellers can tell themselves “at least it didn’t drop”.

When I owned a home, I had a ton of equity in it. I used the HELOC to buy and flip homes.

I would think that industry has come to a dead halt.

Now, I make almost as much on interest income as I did flipping homes. But nothing lasts forever.

On YouTube, I’m seeing a lot of HELOC promos that are aimed at people with high credit card debt.

In other words, nuke your home equity to pay off the plastic.

My Father in law did that. Nuked his home equity to pay of credit card debt. Then he ran up the credit card debt again and went bankrupt.

What happens when you die with credit card debt?

“What happens when you die with credit card debt?”

Usually, nothing since credit card debt is unsecured debt.

“Unsecured” means that the lender cannot pick up the collateral, such as a car or a house, to pay part of the debt. But they can get a judgement, go after the estate, garnish incomes and bank accounts, and a lot more. Talk to a lawyer about it before trying it out at home.

Technically you’re either making interest or bleeding it out.

Making it feels much better.

Last year we used our HELOC as a bridge loan for the between buying our condo and selling our house.

Not having to scurry around looking for a temporary loan or selling some of our other assets was, in our opinion, worth the couple of months high interest we paid.

YMMV

Events in the drunken sailors’ calendar –

Chinese Singles Day (just passed, but bargains still available)

Thanksgiving

Black Friday

Cyber Monday

Christmas

Boxing Day

Chanukah

New Year

Chinese New Year

We can also add Trump’s inauguration day.

Those drunken sailors will go overboard, filled with euphoria. Then, as Trumpification kicks in, the crash in everything except interest rates begins. Or not… who knows.

This election was hilarious! I am now seeing comments from these wahoos that are wondering when our Great Leader is going to lower their bills as well as the cost of groceries! OMG, there is a sucker born every minute!

I’m encouraged to see the American consumer doing ok. I do wish the government wouldn’t row against them or encourage frivolous conflicts.

There are plenty of ways to throw our weight around without shipping malice to the far corners of the world.

What’s the reason for the downtrend in HELOC balances since the GFC? Refis more popular due to the lower mortgage rates?

Yes, cash-out refi with 4% or 3% mortgages beat any other option out there, including HELOCs which would have come with higher interest rates. Some lenders stopped doing HELOCs during that time, including Wells Fargo, because it was just too small to matter.

I know at least one landlord that has taken out a couple HELOCs on property for maintenance/improvements, but this will put him in a precarious position if rents and/or property values fall. The modern mindset is fucked. Look, if you cannot manage you properties (or any business really) such that you make a profit after all your expenses are paid from your revenues, then you probably should not be in that business.

Recently you posted that the mediun wage was about 80k. If that is correct, than half of the country cannot afford to buy any sort of home!

I wonder what that numbers would be, if you took out the top and botton ten percent?

A friend deals in manufactured homes and complains how many cannot meet the requirement for a damn trailer.

Not all is well in flyover country, even with prices being much lower than any decent urban area.

So that was the median household income for all households, including singles. I also posted that the median household income for “family households” is about $120,000. And “family households” are buying most of the houses (singles buy some, but not in huge numbers).

So the median price in the US of a single-family house is $410,000 (NAR). With a 7% 30-year mortgage, the payment is $2,728 or $32,800 per year. Plus taxes, insurance, and maintenance. There is plenty of money left over for other stuff.

Maybe in some areas but not all areas. I live in an area where the average worker makes $40k-$60k annually, average row home starts at $250k, average single family house starts at $600k. Problem was an influx of people who moved into the area from NY buying $60k-$80k homes and now looking to move again and trying to get prices that were paid for homes where they moved from in an area where majority of people can’t afford those prices

plenty of money left over, yet home sales are historically low. FOOP?

“singles buy some, but not in huge numbers”

Wolf – do you have any data on this? I’m one of those weirdos who bought a house all by myself back when I was single.

When I look at property records for my job, I always see a married couple, trust, or LLC listed as the owner – VERY rare to see a single name on a property card…

I bought my (1,800 sf) condo as a single in the late 1980s, and buying a condo as a single is more common than buying a house. I know several people who bought a condo as a single. I know only two people who bought houses as singles, and that was decades ago. We have a commenter here, a widower, who downsized after his wife passed away. But downsizing is different than buying your first home. He likely walked away with some cash.

According to NAR, based on a survey of some recent homebuyers (condos and houses combined): 20% were single females, 8% were single males.

Who said Condos were dead? They were dead wrong. We’ve been doing 2 per week while the single family housing market is dead. Condos are easy to appraise. They are great for Vets and singles looking for a starer home in an overpriced market.

I bought as a single. 2016, just under $200k with a 3% 15y, quality but simple 4br. $1k/month mortgage, more like 1.5k with property tax. Rented to 3 friends at one point but mostly 1 or 2, and even hooking them up with cheap rent, it has been lucrative. Now just me and that cat which I’m more than happy with, and the gf over a few nights a week. I’d see if anyone wants to room but looking to move out of town and rent this place out if land is ever affordable again.

I’m shocked it wasn’t more common when homes and mortgages were dirt cheap. Talked a few friends into buying condos and they sure are glad they did. In hindsight, should’ve done it earlier, and should’ve bought another or some land… Can’t complain though, very lucky. Worth $425k now with no major upgrades and minimal maintenance, not to mention the rental income and some good times.

I bought my first house (a duplex) in 1991 as a single 25-year old Naval officer in Norfolk. Lived in one side and rented the other side out to college kids. Paid rent to my Navy roommate in Newport who bought the house as a single. We moved to Austin to get our grad degrees so we bought a house together. Then we went our separate ways and bought houses as singles in Arizona and Mississippi about 20 years ago. I had a mother who was a Realtor who encouraged me to buy my own home and I always bought houses that were at a deep discount due to death, divorce, or dislocation.

So it does happen but I suspect it may be a generational thing. The younger people that I am around now have trouble buying homes as COUPLES… high apartment rental prices make it hard to save for the purchase of scarce homes.

PS: One reason that there are few singles on deeds is because eventually most people get married… have kids… and buy a bigger house (together).

I have been trying to get into the housing market for a while in Canada, but on a single income it’s almost impossible. Even with rate cuts and new mortgage rules in Canada, it didn’t do much to help. I am in an area which is much more affordable than Vancouver or Toronto, yet I still don’t qualify for much on a salary of $90k + overtime pay and have $0 debt. To afford an average starter home/condo, I need about $200k in a down payment to get the mortgage funding. Something has changed in affordability. I can tell you with certainty that there is not plenty of money left over and I’m not far from that household income. I appreciate there are different variables for different regions which play a role and need to be accounted for, but something is not right. And I can confirm that I do not buy avocado toast or Starbucks everyday despite what older members of society claim 😆.

I think society has put too much emphasis on housing as an investment tool instead of a basic human need. And the market value argument is getting a little old…there will always be high demand for shelter! Its a human necessity and instinct. It also doesn’t hold much weight when you consider that many populations around the world are not reproducing…how is there a housing shortage then? The world population didn’t change drastically since 2020. There are over 8 billion people in the world but so many countries claim there is a housing shortage and affordability issue. Yes, people become displaced, but something is not adding up when this issue is affecting so many different parts of the world. This is a very complex issue that no one seems to be really investigating. We all just seem to point fingers or say try harder. I would be very interested in exploring this further and I think the articles on this page seem to look at things objectively which is good. Maybe this is a topic for a future article.

Just to clarify: The reason why home prices are so high is because BUYERS keep driving them up. When buyers go on strike and refuse to buy, and refuse to pay those prices, then the market stalls, and if a seller wants to sell, or has to sell, it’s going to be at a much lower price, where they can find the first buyer. It’s BUYERS that drive up prices, and that can make prices go down. Sellers – and the hype and hoopla industry overall — are just playing buyers for what they’re worth. But buyers don’t have to play. They can walk away. And that is happening in the US now where sales volume has collapsed.

I’m Canadian as well. My wife and I have 3 grown kids 22, 24 and 27. Only one of the 3 will ever be in a position to buy a house. The youngest is a Graphic Designer, the middle a Civil Engineer and the oldest a Social Worker. Only the middle will ever be able to afford a home. The other 2 will not even be able to retire. Yes housing in Canada is equivalent to buying a stock for the older generations. Where we live in Nelson, BC the cheapest handyman special house is 500k and a new buyer is looking at a 4.5% mortgage.

Private equity firms bought slews of homes post-2008, instigating the shortage of housing and an explosion in prices

Toronto average prices on the Zolo index dropped ~$300K in the last month or so, from $1150K to $866K, not much room for HELOCs there for most recent buyers. Listing to sales ratio now about 8.6 to 1, and YOY drop 23%, quarterly drop 20%.

There’s usually a fall drop until January or so, but nothing like this.

Condo market dead, dozens cancelled, but apparently we still have the highest crane count in North America, finishing up the work in progress projects. Many assignments of spec units show 20 to 30% losses.

One project (‘The One’) went into receivership owing $2B a few months ago and they’re trying to flog it off for $1.2B, said to be a dream number. It’s being reconfigured for smaller and more units on the upper floors.

Technically you are correct that incomes rose compared to mortgage balances. But looking at the graph makes it clear that the rise is so insignificant that it doesn’t matter. What it does show is that everything is kind of stuck right now. Everyone is waiting for something to happen.

Everyone is Waiting for something to happen?

– if all asett classes are grossly inflated, and the current moment is in apparent stasis,

Is the populace at the top or bottom of the rollercoaster ride?

I don’t pick a bottom on probability.

I wonder how those h e l o c ( sorry spell check doesn’t like that) rates will change in the next year, as inflation stays sticky and treasury undergoes a disconnect from reality (or at least current structure).

Granted, treasury and the Fed have influenced rates a great deal the past two years — but potential restructuring of national debt (with new policies and laws) may have very weird correlations with mortgage rates and homeowner borrowing.

As an example, a new Fed may sell MBS at a loss as it lowers rates, as the bond vigilantes freak out about the deficit.

“ Torsten Slok of Apollo notes, is that America’s government deficits are now so big that the ratio of debt to GDP is about to smash through the 100 per cent level, and could soon hit 200 per cent. This means the US government will have to roll over $9tn of debt (or a third of the total) in the next year, expanding auction sizes by some 30 per cent.”

I’m very curious about mkt stability going forward!

This is why the Fed wants banks sitting on a huge pile of treasures – so they can park em at the Discount Window for a loan, and to keep a bid under bonds as the Fed is no longer a buyer with QT…

There’s a huge disconnect in mkt valuations with everything.

I’m thinking stocks have to drop 20%, dragging a lot down with it — I definitely don’t think we get traditional recessions or mkt normalcy ever again — but I think a mkt correction has to take place one way or another.

Either the equity mkt has to drop or bond yields have to explode way higher — there’s a disconnect between current value and projected future value. The s&p can’t have an earnings yield next year of 4.34% based on classic valuation, eg, 10 yr currently at 4.44% + the spread on BBB effective corp yield at 1% — fair value is totally screwed up and definitely showing up in Buffett Indicator.

It’s making sense to me that so something will break as inflation drifts higher with excess euphoria thinking stocks are going to rocket.

I feel like I’ll be banished from the Wolfstreet campfire chats and seem like an insane hobo, but I’m not liking what I see in the house of mirrors!

I told you years ago to start your own blog where you can write whatever theories you come up with about whatever you found on the internet, which is what you do a lot of times. You often post several of these a day. I’m now deleting all your longer posts without even reading them. They don’t belong here. And I don’t want to read them anymore. They belong on your own blog. This is not a blogging platform where you can say whatever.

I recommended years ago that you get a free WordPress blog account. But you said you were too lazy to do that.

Now I’m recommending that you get a Substack account. It’s super easy, anyone can do it, it’s free. It also has an email function so you can send your posts to subscribers via email, if you want. I’m serious.

That guy is redundant…

Cash out Refis are out due to the high interest rates.

Sales of 3% mtg homes to move are out.

New home purchases at current rates and interest rates are unaffordable.

People will stay put and improve their homes.

Helocs will be the only game in town. The interest is only deductable if it is put into home improvements.

Even then, who can itemize these days?

MW: Investors are bracing for higher-for-even-longer interest rates

The Fed told them two years ago. And they’re just now figuring it out?

Yes. Better late than never!

I’m curious to see how far TLT will fall. $85? $80? Lower??

Lower.

The problem is most HELOC’s are variable rate. So a lot of people are seeing their monthly bill increase

They decreased the last two months. The one I have is prime minus 1 percent, so 6.75 currently. The best you can get now is minus .5 percent, so 7.25 currently at that bank, but I opened it 6 years ago and the terms were more favorable. I’ve used it and paid it off several times in the last 6 years to varying degrees. It keeps me from needing any kind of “emergency” funds sitting uselessly in my bank account as I save and then spend to renovate my house or (in the past) a rental. I love mine, just not as much as I did a few years ago when the rate was dirt cheap.

Why go into debt at all?

“Mortgages don’t get in serious trouble until home prices crater and people lose their jobs at the same time.”

Has me thinking about the impact of tarrifs, grocery inflation as we deport all agriculture workers, and a lot of government jobs that are going to be eliminated the the new Efficiency Department since the Federal Government is the largest employer in the country.

The civilian workforce at the federal government is about 2 million. Total US employment is 161.5 million. Federal government workers are 1.2% of total US workers. If Musk et al. succeed in firing 200,000 federal workers (good luck!), spread over six months, that’s about 33,000 per month.

There are currently 6.98 million people who count as unemployed. The monthly fluctuations vary up and down 50,000 to 200,000 so it would just add to those monthly fluctuations. It would barely move the unemployment rate.

People have completely crazy ideas about the share of federal government workers in overall US employment. It’s just 1.2%.

The military alone is over 3 million. Do not lie

Military, by definition, is NOT “civilian.” If you’re in the Army, you’re NOT a civilian employee of the federal government. You’re a solder.

Of the civilian employees of the federal government, the largest group, 500,000 belong to the VA and mostly staff VA hospitals and healthcare facilities. You want to take those hospitals away from our veterans?

Why bother to earn money when you can just borrow it?

I’m Canadian and not as up to speed on U.S. politics and the economy, but if the number of fed employees is that low and the number of cuts won’t make a huge impact in unemployment, why are so many people supporting the claim that government needs to be downsized? The numbers you posted don’t seem scarey. I don’t understand the anxiety then, and it doesn’t seem like the economy is in that much danger?? Are the media and politicians making it out to be worse than it is?

It’s not the number of employees that’s the problem — sure they could trim some but it wouldn’t make a lot of difference — it’s the hundreds of billions of dollars that the government hands every year in various forms and subsidies to Corporate America, such as the Chips Act, that is giving chip makers billions and tens of billions each; and the EV subsidies, and the various tax credits, and a lot of pork-barrel spending that goes to each Representative’s district which is why it’s so hard to cut spending because each Representative wants to keep the money flowing into their districts.

Hey Wolf, you mentioned businesses might want to worry about debt. Can you share any additional information about that? I’m in construction, and am wondering if some of the big suppliers or maybe big builders might be in trouble.

The big publicly traded builders are not in trouble. They’ve got lots of cash and access to exuberant capital markets, and they’re very profitable right now.

Someone here said recently that smaller builders are always in trouble because they never have enough cash.

Credit risk goes company by company. The industry might be doing great, but for whatever reason, this one company runs into difficulties. So you cannot generalize.

Thanks for the reply.

Yeah, I’d agree that small builders’ fortunes can change on a dime. I guess the definition of “small builder” could vary but anyone doing under $10m/yr can go from riches to rags (or in the other direction) in a few years. I’ve worked with two builders now, as a subcontractor, that were doing about $10m/yr in the 2010s and are doing $100m/yr now. Both started in windows and doors (my specialty), one made it big by adding roofing into the mix and another by adding kitchens and baths.

I’ve seen the opposite happen. A prominent deck builder around here went from dominating the metro area to not paying his subcontractors. He’s still doing alright, but he’ll probably lose his license if he keeps burning bridges and if DOLI gets involved.

The easy money in construction is gone, and my business lives off referrals. I’ve been keeping busy doing punchlist carpentry for a large builder, which is still in demand.