Revenge of the floating-rate CRE loans: Ironically, use of floating-rate office loans ballooned as interest rates rose.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The delinquency rate of office mortgages that have been securitized into Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS) – investors on the hook here, not banks – spiked to 7.4%, powered by floating-rate mortgages, whose delinquencies spiked to 20%.

Data provided by Trepp, which tracks and analyzes CMBS. These are loans that have not paid interest for 30 days or more, after the 30-day grace period expired.

In 2012 and 2013, delinquency rates of office CMBS eventually exceeded 10%, as one of the many consequences of the Financial Crisis and the Great Recession, not interest rates, which the Fed had pushed toward zero back then.

This time around, landlords are dealing with two big issues even as the economy is growing rapidly: ballooning vacancies and much higher interest rates that are tearing up floating-rate loans.

Floating-rate CRE mortgages.

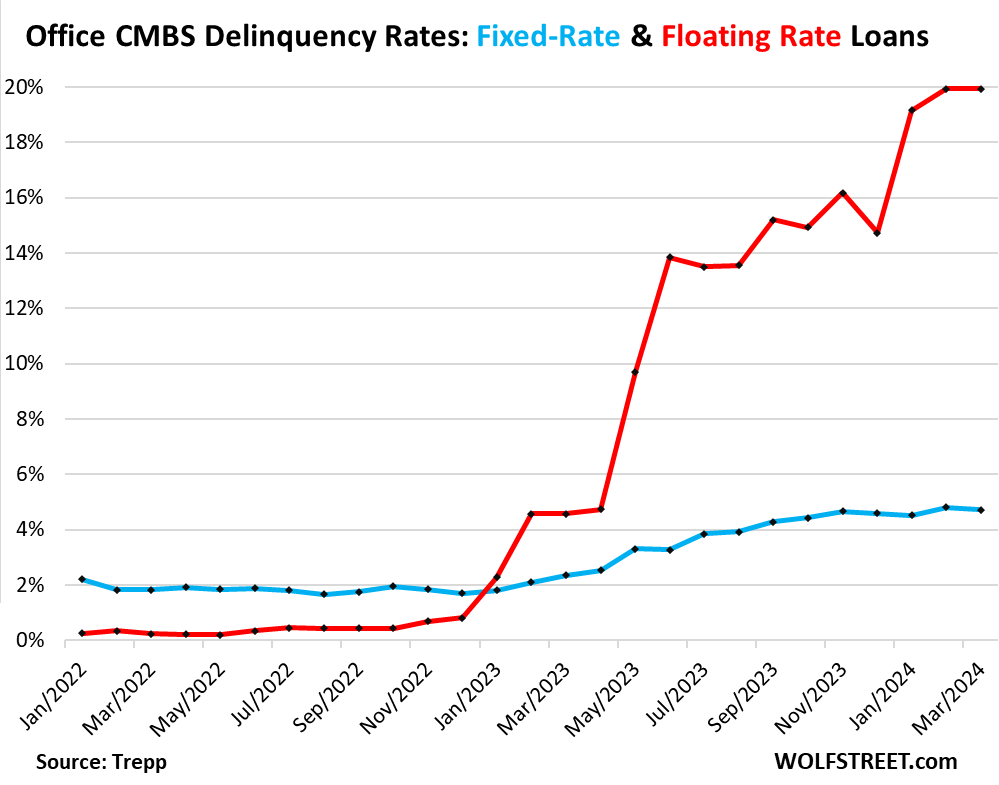

During the now bygone era of near-0% policy rates and massive QE by the Fed, the delinquencies of floating-rate office mortgages were below 0.5%, (red in the chart below), and well below the 2% delinquency rates of fixed-rate mortgages (blue in the chart below).

But during the current era of historically more normal interest rates, delinquency rates of floating-rate office mortgages rose to 20%, while delinquency rates of fixed-rate mortgages rose to 4.7% (data via Trepp):

CRE mortgage rates have more than doubled, and floating-rate mortgages adjust to them. There loans are often interest only, and when the rate doubles, the payment doubles. This was behind many of the office-loan failures we’ve discussed here for the past two years.

Many of these loans have relatively short terms, such as two years, or five years, and then there is the added risk of the landlord not being able to refinance the loan at maturity because the new rates are so high that the property is not economically feasible at the amount needed to pay off the maturing loan.

In many cases, landlords just walked away. For example, Blackstone walked away from an office tower in Manhattan it had purchased for $605 million in 2014, and later refinanced with an interest-only floating-rate mortgage. The special servicer, representing the CMBS holders, has now sold the loan for $200 million. The losses were spread across equity and debt investors, not banks. The new owner, sitting on this much lower cost base, might develop the tower into a residential property.

Office availability rates have reached 30% and more in some cities, and are above 20% in most cities, due to a structural problem as Corporate America has discovered it doesn’t need, never needed, and won’t ever need all this office space that it has leased. High vacancy rates mean the cash flow from rents is diminished, and that makes it harder to make the payments of any type of mortgage – fixed or floating rate.

There is not a good way out, buildings are being drastically repriced, quite a few of them are sold for close to land value to be redeveloped into residential. And it’s a huge mess. Lower mortgage rates, should they re-appear, won’t alter the structural problem.

The growing share of floating-rate office loans.

During the era of interest-rate repression, nearly all (98%) of office mortgages were fixed-rate, according to Trepp. Makes sense as interest-rates were very low.

But when interest rates began to rise, landlords needing to finance or refinance a building switched to floating-rate loans because rates were a little lower than fixed rates at the time. Apparently, they were hoping all along the way that rates wouldn’t rise any further, and would soon drop again, as the Fed would be forced to pivot or whatever, which has turned out to be a colossally wrong wager.

Currently, about 37% of CMBS office loans are floating rate (red), and 63% are fixed rate:

Overall CMBS delinquency rates.

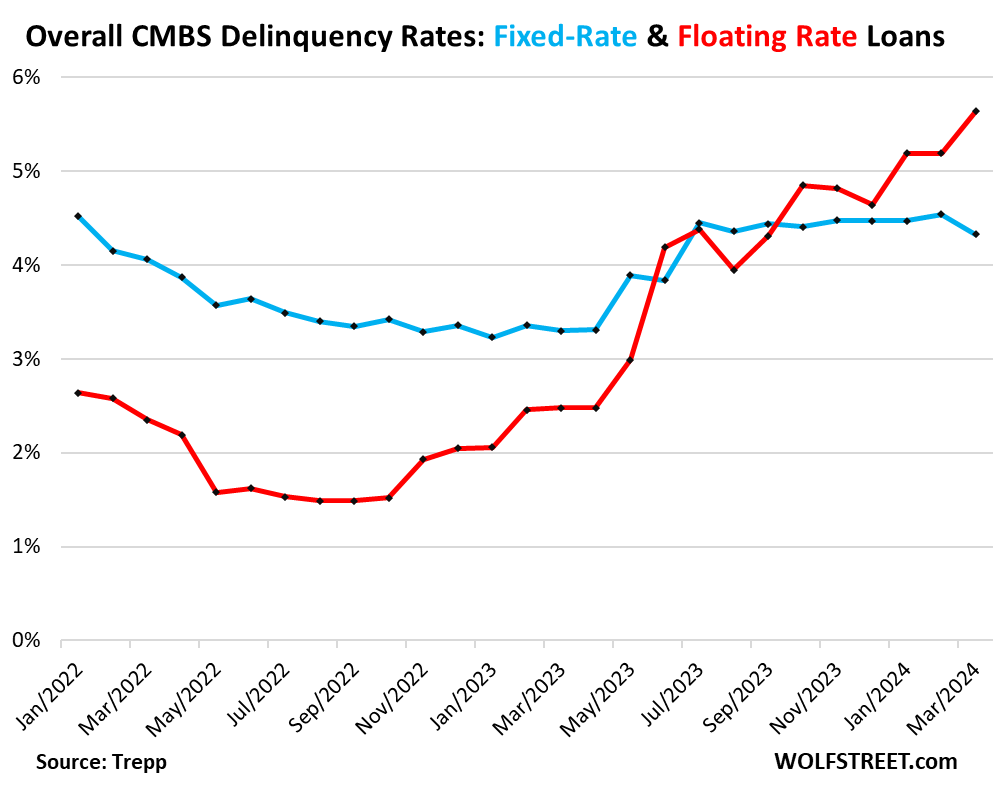

The overall delinquency rate for mortgages in CMBS mortgage pools jumped to 5.1%. The office sector is now the worst performing sector of CMBS, even worse than retail and lodging. Still in good shape in terms of delinquencies are multifamily, despite some issues, and industrial (warehouse space, fulfillment centers, etc.):

- Office: 7.4%

- Lodging: 6.0%

- Retail: 5.9%

- Multifamily: 1.3%

- Industrial (warehouse space, etc.): 0.4%

The divergence in overall delinquency rates between fixed-rate and floating-rate loans is quite something, with much lower delinquency rates for floating-rate loans (red) during the era of interest-rate repression, in the 1.5% range, than with fixed rate loans during that time, at over twice that rate.

Then the free-money era ended, and delinquencies among floating-rate loans began to surge, while fixed-rate loan delinquency rates plateaued:

Repayment defaults are an issue that fixed-rate loans face – when, for example, a 3%-loan matures and has to be refinanced with a 7% loan, while rent revenues don’t cover the payments for the 7% loan. So lenders will not lend on the property, and the borrower cannot pay off the existing loan when it matures and ends up defaulting on it. But many floating rate loans get washed out before repayment even comes up.

Loans that missed their payoff dates but continued to make interest payments are not included in the delinquency rates here. Missing a payoff date can mean that the borrower is negotiating with the lender, or that a loan extension is in the works, etc., or that the landlord cannot refinance the property. According to Trepp, if loans that missed their maturity dates, but are still making interest payments, are included in the overall delinquency rate, it would be 5.8%, instead of the current 5.1%.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

This is good news; however, such enthusiasm needs to be tempered by the delinquency graph that is still only about half (5%) of the 10+% that it historically needs to be at. Hopefully, some of those fixed rate loans are “negative amortization.”

What does this mean to broader economy and drunken sailor spending? Probably nothing burger at best…nothing seems to stop the good time we’re all experiencing, black swan event this isn’t it for sure..

Residential loans from one year or so are in the same boat. People took out many loans with adjustable rates and now are getting the new rate and payment. This will Couse increased delinqicies. Yes the percentage of adjustable rate loans are low but has increased in the last few quarters. Could this force some sellers to list the home to get out from under the loan? Little reported is the existence of many old adjustable loans written around the time of the last housing crash. These old loans have been a windfall when rates were at giveaway prices but have now gone through the roof. One client of mine had enjoyed a payment on a rental of $350 at the bottom and is now facing a $980 payment. These owners are now facing huge payments that take all the fun out of the home. Refinancing out of the loan is problematic with todays rates. Sure there is most likely vast amounts of equity and a HELOC is an option but qualifying may prohibit refinancing and selling may be the only option. Wolf do you know if this is showing up in the numbers? Thank you for your wonderful work.

“ Little reported is the existence of many old adjustable loans written around the time of the last housing crash. These old loans have been a windfall when rates were at giveaway prices but have now gone through the roof.”

Anyone who didn’t refi out of an ARM into a 15 or 30 year fixed mortgage over the last few years deserves the oncoming carnage. I can’t imagine there are many people that were that foolish.

Don’t rely on that manna from heaven at 3 percent for 30 years.

There are a thousand reasons that would have made such people sell, and urgently

How common are/were ARMs in the US?

The housing insanity has finally arrived in my area of central Wisconsin.

My small town is based on a paper mill. So you probably wouldn’t find it difficult to believe we’ve had a depressed economy for about 20 years. The local mill has been sold at least 5 times. Ironically, the current owner is Chinese. Listening to the stories of my sister and her husband, who both work at the mill, points to extreme cultural differences between management and staff.

So you might imagine housing prices have dropped through the floorboards. Rather, I would describe it as plateauing at a lower level… Until lately.

My neighbor just sold his home. He has been my neighbor for 5-10 years. He didn’t mention it, but I assume he added unto the price 5-10 years worth of what he considered normal appreciation. If I had to guess it would be a total of 25%. Remember, this is a depressed area.

He said he sold it without even listing for $40k above asking. The new owner is from a neighboring town 20 minutes away. He said prices were even higher there.

I bought my home from my mom’s estate in 2018 when she passed away. Naturally, I applied my neighbors experience to see what my home is worth. I figure it’s about 150% gain compared to what I bought it for.

This is just insane!

Wow, office RE doing worse than retail RE? That’s also a little ironic.

DM: Is this why gas prices are so expensive? Shell smashes forecasts with $7.7 billion profit in just three months – as pump prices hit more than $7.25 a gallon in some states

The profit – $1.3 billion higher than expected – comes as gas prices hit an average of $3.70 .In some parts of California prices have skyrocketed to $7.29..

They should gas up in Lafayette Indiana for less than half price. It’s all in the low taxes because we’re all hicks near French Lick.

Illinoisans shop in Dyer Indiana for their booze and cigarettes as if they are bootlegging like Joseph Kennedy.

Yup. It is the gas tax difference. Here in Wisconsin I paid $3.19 gallon last week for the cheapo unleaded. I don’t buy at Shell. The local favorite is Kwik trip.

QT is better quality gas than shell!!

Pardon my ignorance, but where exactly in the market are these delinquencies felt? I haven’t seen much movement in any CMBS or CLO ETFs available to retail investors. In fact, junk bond yield spreads have been narrowing over the last year. Is it mostly private investors holding this debt? Maybe it’s not available to retail because this debt is worse than junk(CC and below/unrated)?

As we said here many times, this stuff is spread so far and wide globally, that it’s hard to see the impact. It’s in pension funds, life insurers, bond funds, diversified investment funds, banks, etc. around the globe.

Which is why the Fed isn’t really concerned that much about the CRE problems in general. The majority of the holders are investors around the globe, and the US government with its huge multifamily debt holdings. And even among banks, US CRE is spread across banks globally, not just in the US. US CRE debt had long been considered a safe investment, especially CMBS whose structure gave investors a sense of security as long as they bought the high-rated tranches, and this has appealed to investors globally.

You can see some impact in office REITS and CRE mortgage REITS, for example, whose prices have plunged.

“Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS) – investors on the hook here, not banks”

Quick question – since banks have both loan books and securities books, how can we be sure that no CMBS isn’t in fact ending up at banks – *in their securities book*?

Basically, I conceive of banks’ loan both as the loans they originate and hold and the loans/syndicated loan chunks they buy from other banks. Broadly speaking, loans usually have more protections/safeguards built into them and are usually originated/held by banks.

All the flavors of mortgage backed securities (CMBS, RMBS, etc.) usually/frequently start out life as “loans” (with fewer safeguards/protections) originated/structured/underwritten by banks…but then relatively quickly get sold off to various MBS packagers (Wall Street, etc.) who chop up, combine, re-combine, and tranche these myriad mortgage loans from all over into marketable *securities* sold into the public market (where all the non-bank players you list can also buy the myriad pieces).

But…that isn’t to say that banks can’t/don’t buy these mortgage backed *securities* and place them in their securities “book” (along with a ton of US Treasuries, etc).

Banks love ’em some apparently “secured” investments (which most MBS tranches are), they love the inherent/apparent diversification of MBS, and the banks can pick and choose the tranches they want by stratified protection level (in theory at least).

Given those factors, I’m pretty sure some banks at least are buying MBS but place them in on their *securities* not loan books.

Is there some aggregate FDIC (or other) metric that say this isn’t going on?

(I’d agree that the banks are probably hugely biased towards the enormous, Fed guaranteed *ResidentialMBS* mkt – because of the Fed guarantee and therefore regulatory risk-weighting) but I’m willing to bet there are plenty of banks who have taken flyers on un-guaranteed CMBS too.)

You can take banks’ exposure to CMBS off your worry list. It’s just another one of your homemade conspiracy theories.

All 4,000-plus US banks combined hold only $98 billion in non-government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities, and most of these are residential MBS, not CMBS.

Even if all of the $98 billion in non-government guaranteed MBS are CMBS, which they’re not, they would only amount to 0.4% of the $23 trillion in total bank assets 🤣

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/current/

To answer Dan’s question, these losses are felt by the B-Piece buyers, the purchasers of the riskiest tranche of the CMBS securitization. Usually hedge funds or large PE firms. They get appraised out as these loans default and the next tranche takes over as Directing Certificate Holder. I think Trepp notes the DCH? Wolf, would be cool if you did a piece on which B-Piece investors are taking losses. It’s a small group buying them over the last few years, <10 I think.

Losses have gone up all the way to AAA pieces because the loss protection pieces have been too small to absorb the losses because no one wanted to build in that kind of plunge in value. For office towers that sold at foreclosure auctions, some CMBS have had loss ratios of 80% to 100%, after fees. Almost no one walks away from those unscathed. I documented some of those here.

I have a mix of mortgage REITs shares substantially in the red that I bought 3-4 years ago when uninformed. Wondering if they’ll ever break even but good lessons and reminders of what not to invest in again.

Can average Joe’s buy credit default swaps on rotten office CMBS? I would guess not, that is reserved for the big boys like Michael Burry.