Supply chains begin to shift back to US suppliers, “due to tariffs.”

Two US manufacturing reports were released this morning, one showing the fastest decline since June 2009, and the other showing an increase in growth, and given the bad numbers recently, the fastest growth in five months. So get ready for mild whiplash.

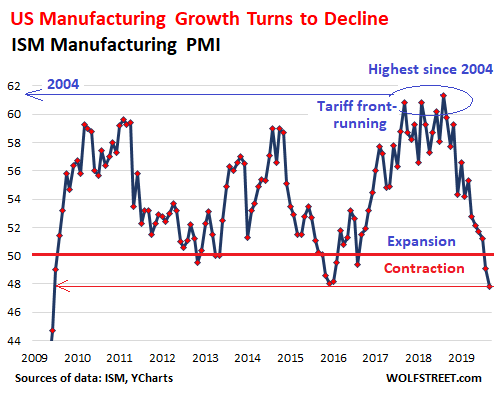

The bad news came from the Institute of Supply Management (ISM), whose Manufacturing Report on Business for September fell to 47.8. In this diffusion-type index, a value above 50 means growth and a value below 50 means decline. Today’s reading was the second month in a row in decline mode (below 50), and the fastest decline since June 2009.

This decline followed a huge surge peaking in 2018 with the fastest expansion since 2004. This surge was the result of efforts by US and foreign industries in 2017 and 2018 to front-run any tariffs. They over-ordered and over-produced and over-stuffed their warehouses with inventory, and those excesses are now being wrung out of the system (data via YCharts):

These types of indices are based on how a panel of executives of manufacturing companies – names are not disclosed – see their own businesses. In terms of the ISM Manufacturing report:

Demand contracted, driven by export orders: New orders translate into future production, and so this is not indicating a bottom just yet:

- New Orders contracted in September (47.3) at about the same rate as in August (47.2), dragged down by New Export Orders.

- New Export Orders plunged in September (41.0), after a sharp contraction in August (43.3)

Production contracted faster in September (47.3) than in August (49.5).

Backlog of Orders fell faster in September (45.1) than in August (46.3), as production is now clearing the backlog.

Employment contracted faster in September (46.3) than in August (47.4).

Supplier Deliveries expanded in September (51.1) more slowly than in August (51.4)

Inventories contracted in September (46.9), as companies were trying to whittle them down, from the inflated levels after the front-run efforts in 2017 and 2018. Customers’ Inventories also contracted in September (45.5), from previously elevated levels to “about right,” as the report said.

Prices declined a tiny bit in September, near the flat line (49.7) compared to the steeper decline in August (46.0).

The report summarizes: “Global trade remains the most significant issue, as demonstrated by the contraction in new export orders that began in July 2019. Overall, sentiment this month remains cautious regarding near-term growth.”

Of the 18 manufacturing industries, 15 reported declines and only three reported growth: Miscellaneous Manufacturing; Food, Beverage & Tobacco Products; and Chemical Products.

The comments that panelists provided, reflected “a continuing decrease in business confidence.”

A second opinion.

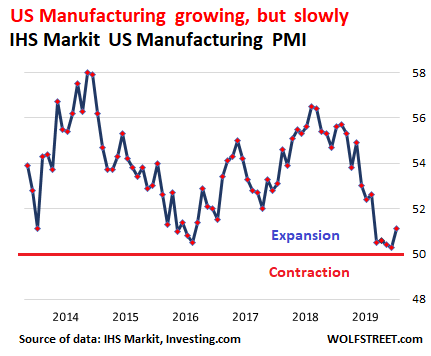

The IHS Markit U.S. Manufacturing PMI, also released this morning, was in expansion mode for September (51.1), after four months of being near-flat:

“September PMI data indicated a marginally faster rate of improvement in the health of US manufacturing, though the overall picture remained one of a struggling goods-producing sector that has suffered its worst quarter since 2009,” the report said.

This expansion of the headline PMI was largely driven by the upturn in production – while modest, it was the fastest since April, based on “slightly stronger client demand and efforts to clear backlogs.”

New orders expanded, driven by an increase in domestic client demand, but weighted down by export orders that fell the second-fastest in nearly five years.

Employment expanded “marginally,” as firms were encouraged by rising new orders and production.

Input prices rose due to the “impact of tariffs,” but wait, “a drop in demand for inputs kept cost rises relatively muted.”

Output prices also rose “modestly,” as firms “sought to pass on higher costs, while maintaining efforts to be competitive.”

In terms of their output expectations for the next 12 months, “firms expressed a greater degree of confidence”; and “the level of optimism” reaching “a three-month high but remained relatively subdued overall.”

Shifting production back to the US:

The report included a fascinating observation on how some supply chains were shifting back to the US to avoid the tariffs, but this isn’t easy to do quickly, and so “supplier performance deteriorated further as firms increasingly reported a change to domestic suppliers, due to tariffs, with vendors struggling to deliver goods to manufacturers amid capacity issues.”

Despite the improvement in the PMI for September, the very weak July and August readings produced the weakest quarterly reading since 2009. The report added:

“It’s also far from clear that the trend will improve in the fourth quarter. Inflows of new work remain worryingly subdued, to the extent that current production growth is having to be supported by firms increasingly eating into order book backlogs.”

And reminiscing about the happy times of front-running the tariffs: “The current situation contrasts markedly with earlier in the year, when companies were struggling to keep up with demand. Now, spare capacity appears to be developing, which is causing firms to curb their hiring compared to earlier in 2019 and become more cautious about costs and spending.”

In summary, Manufacturing is either in a mild recession and perhaps coming out of it, or sinking deeper into a not-so-mild recession, depending who does the counting.

How important is manufacturing to the US economy?

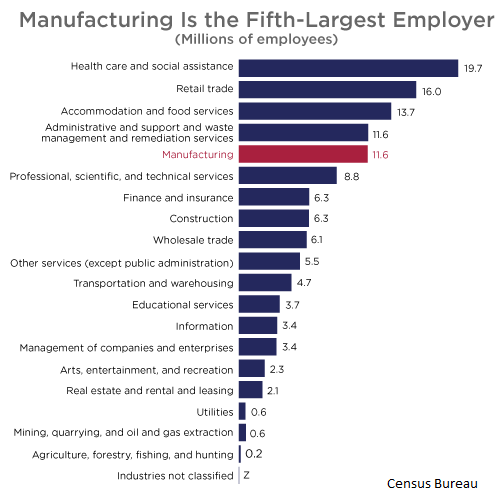

In terms of employment, manufacturing is the fifth-largest sector with 11.6 million workers. And it pays well, with an average annual payroll of $57,266 per employee, according to the Census Bureau today:

These manufacturing jobs are not what they used to be, as automation and the challenges it brings have taken over. “These workers are not only highly skilled, but extremely well-educated,” the Census Bureau says. Based on its 2016 Current Population Survey, nearly 30% of manufacturing employees age 26 or older had a bachelor degree or higher.

So manufacturing is important. A decline in manufacturing puts a damper on the US economy. And relying more on suppliers in the US — the first signs are now being reported — would boost the economy.

But services dominate the US economy. In the US, the biggest service sectors in terms of dollars are finance, insurance, and health care. According to the World Bank, services account for 77.4% of the US economy as measured by GDP, behind only Macau, Hong Kong, and Luxembourg. In Japan, services account for 69.1% of GDP, in Germany 61.5%; and in China 52.2%.

In the US, services provide 79.1% of the employment. In Japan, 72.1%, in Germany 71.6%, in China 44.6%.

In other words, the manufacturing recession that has spread around the world is impacting other economies far more than the US economy. It might pull Germany into an overall recession even if services hang in there. But in the financialized US economy, services would have to slow, meaning finance, insurance, and healthcare, which dominate services, would have to slow. But so far – industry insiders are being heard knocking on wood – this hasn’t happened yet.

Services are Hopping. And the #1 Biggie is Hopping the Fastest. Read… The Financialization of the US Economy

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

To summarize.

America no longer rolling over on trade. This affected some American exports but really hit Germany and China. Some manufacturing is actually even coming back to the states.

And everyone loves America tobacco except American politicians.

>And everyone loves America tobacco except American politicians.

And oncologists. It helps the bottom line.

Germany’s problems have very little to do with US tariffs. If you want the short and condensed but incomplete version, the country has had far too much manufacturing growth over the past 4/5 years and as a whole invested expecting that pace of growth not merely to continue but to actually accelerate. It’s the same dynamics that is playing all over the manufacturing districts of Europe and the reason why everybody is wailing but macrodata are not even remotely indicative of the mildest recession.

China was part of the reason for this unsustainable growth and when earlier this year a massive round of stimulus was announced the champagne was brought up from the cellar, only to be brought back precipitously after realizing that mass of yuan was achieving nothing. China has problems and we don’t know what they are: their propensity for retouching, embellishing and downright inventing economic data makes a diagnosis impossible. But us Westerners believe everything Beijing tells us (just like we did in 1968) so now that the PMI has been “adjusted” let’s bring up that champagne and uncork it before we realize this is another fraud.

“So manufacturing is important. And a decline in manufacturing puts a damper on the US economy.”

Let’s say manufacturing company ABC moved its operations to Mexico/India/Bangladesh because of their lower cost of labor.

Since the employment is not in US territory, ABC’s overseas employees are not counted. Yet, if the factory’s output is sold mainly in the US, shouldn’t there be an asterisk next to the manufacturing category to account for those non-US employees?

Maybe the numbers are not known or statistically insignificant and I’m splitting hairs.

Thanks for the great article!

Old Dog,

ABC’s employees in Mexico are not counted as US employees.

ABC’s production in Mexico is also not counted as US production. It’s counted as IMPORTS. No asterisk needed, just Mexican production by Mexican employees. It doesn’t matter who owns the company.

What really counts in an economy is the private sector, tax-generating employment, of which, Manufacturing stands head and shoulders above all others. IMO

I’ll happily take a quarter or two of “bad news” in order to have a healthy long term manufacturing sector in the US.

Exactly.

The establishment and academic dirt bags are hoping the body-politic can’t see past the short term. (note- I have spent some time in faculty lounges in the largest higher education institution in the world. I know how they think.)

If the US is going to offer social welfare, it has to control the number and documented citizenship of those who may be eligible for it.

It’s not ‘a quarter or two’.

It will take a large, consistent effort for a decade (or even two) to first reestablish and then catch up with the current state of the art design and manufacturing skills for mass production that were lost to China, South Korea and Japan.

With the political effort mainly going into weakening standards and the deficit funding of the MIL-SEC- and FIRE- industries, I don’t see that will happen. Rather, a lot more ‘Boeing 737 MAX’ will happen.

Reversing 3 or 4 decades of supply chains around the world will not happen in a couple of quarters. A lot of infrastructure is needed, old manufacturing plants don’t fire up by just turning the power back on.

Or let’s just click our heels 3 times, “there’s no place like the past”.

Excellent read.

“This is an overview of the complexities and issues that a company must deal with in order to relocate their factory out of China and place it back in the United States. It’s not as easy as it sounds, and we discuss the issues involved independently outside of the contentious American political scene.”

https://metallicman.com/laoban4site/the-logistics-of-relocating-a-factory-from-china-back-to-the-united-states/

Interesting dichotomy between two surveys. One wonders why so different? Notionally these are both responses from purchasing and supply execs in manufacturing companies, weighted by contribution to the economy (GDP).

So I dug a little and noticed that the MarkIT statement of their survey methodology is notably more detailed than PMI’s:

IHS Markit: surveys sent to panel of 800 manufacturers

ISM PMI: “data compiled from … executives nationwide” (no number given)

Markit: Data collected 12-24 September

ISM: Doesn’t say (other than “September”)

So if ISM is polling a larger (or smaller) panel, or if they did so earlier (or later) in the month, that could impact the results.

P.S. ISM is headquartered in Tempe, AZ. IHS global HQ is in London. Not sure if either has an underlying conflict of interest of any kind.

Wisdom Seeker,

Short-term the two rarely match. But their trends over the longer term run pretty close in parallel. You can see the front-running surge in both charts, and you can see the peak in both charts, and now the hangover. But the magnitude differs, as does the timing.

I like to look at both of them together. Each gives a glimpse of manufacturing from a slightly different angle.

Then the question is whether the Markit higher number is the harbinger of a new uptrend, or just an outlier in an ongoing downtrend….

It would be nice if both companies merged and then we would have one number.

Or.. we can do our own merging by adding 47.8 and 51.1 together and then dividing by 2.

Voila. 49.45. Contraction it is !

I am more interested in Thursday’s non-manufacturing. Especially the employment index

the manufacturing recession will spread to other industries. the manufacturing will not be consuming services so you are wrong that the rest of the economy will be ring-fenced.

There was an uptick in Chinese PMI in Sept. It is nearly flat line.

India Sept. PMI above 50.

Japan Sept. PMI below 50

Seattle real estate prices oscillating downward.

September US auto sales disappointed.

manufacturing’ is so much an old economy thing, services are where we wish to be. A nation of servants ruled over by a few oligarchs and their paid Washington enablers.

Three zero-hour jobs for every able bodied wage earner.

Speaking of ‘services’…. Quite a few banks have been instituting layoffs, perhaps getting ahead of the curve.

Nicko2 who need bank employees anyway if they are going to eliminate cash and go with crypto AI will rule the day Aaron Russo was spot on

We have heard the high oil prices are great for the US economy.

But from the image above Mining, Quarrying and Oil and Gas is only 0.6% of the total employment.

Oil and Gas is obviously a tiny fraction of that.

Can’t see how high oil price are good for the US economy given that this would result in inflationary head winds for close to 100% of all workers.

It’s a petro-dollar, not petro employer. Trading high volumes of oil requires fewer people than producing high volumes of cars or trucks.

Rat Fink,

No, that’s not how the Census Bureau’s classification system works. It goes by location where the person works and is based on NAICS codes. I have received those employer surveys. They’re very specific.

A person working physically in a mine or on an oil rig would be given a NAICS code that is a sub-category of “mining.”

But the oil industry is full of high tech, finance, insurance, research, etc. that all fall into other categories. Go to Houston and look at the energy related office towers. None of those people working there are classified as working in “mining.”

The energy business buys professional services from other companies – energy related services are a huge thing. And few of those people are in “mining.”

The energy business has large transportation needs, and those people are working in trucking, railroads, etc., which are subcategories of “transportation and warehousing”

There is a lot of construction for the energy business (pipelines, terminals, office buildings, housing in the oil field, etc.), and those workers are classified as “professional services” (architects, engineers, etc.) or “construction” but not “mining.”

The oil & gas business buys a huge amount of equipment and supplies, such as high-tech drilling rigs, specialty trucks, drill bits, pipes, power generators, chemicals, etc. None of these people working in these industries are classified as “mining.”

The oil and gas industry buys or develops a lot of software, and those people are not in “mining.”

The oil and gas industry buys a lot of computers, specialty tech equipment, etc. and none of those people are in “mining.”

An easy example to understand: Amazon employees are NOT included in “retail” unless they work at a Whole Foods or an Amazon brick-and-mortar retail store. Amazon warehouse employees are in “transportation and warehousing,” and Amazon’s engineers are also in other categories, not in “retail.”

I’m surprised that nearly 20million people are employed in the healthcare and social services sector.