“This emerging trend highlights just how much risk some investors are willing to take in the current environment.”

The Fed’s explicit purpose of “removing accommodation” – hiking interest rates and unwinding QE – is to tighten the ultra-loose “financial conditions” that have prevailed for the past nine years. By tightening “financial conditions,” the Fed is trying to bring markets “gradually” – rather than all at once – back to earth: higher yields, wider spreads, higher risk premiums, etc. By definition, this entails lower asset prices for investors and more expensive and harder to get credit for borrowers, particularly at the riskier part of the spectrum. But for now, the strategy is not working.

The longer the Fed’s strategy is not working, the longer the Fed will raise rates, and the higher the risks will be that, instead of working “gradually,” as the Fed always says, its strategy is going to work belatedly but all of a sudden – which would make for a brutal surprise.

Just how widespread is this? Take asset-backed securities (ABS) backed by subprime auto loans. Subprime auto-loan defaults in March hit the highest level since 2008 though they’ve backed off some. These structured securities have tranches with different credit ratings. At the time they’re issued, the tranches may range from AAA to deep-junk B. The lowest-rated tranches would take the first loss, and rising default rates make those B-tranches very risky. Normally, the specialized subprime lenders will retain the lowest rated slices because investors have no appetite for them. But even that is changing.

Due to the higher yields those B-rated slices offer, there is now such demand for them that the risk premium – the difference in yield compared with Treasury securities – has been compressed by 68 basis points (0.68 percentage points) between April and June, according to ICE data cited by Bloomberg. But the risk premium of higher rated BB slices contracted only 20 basis points, and the risk premium of AAA-slices didn’t even budge.

A wider spread in yield – the risk premium – is supposed to compensate investors for the additional risks they’re taking. But those risk premiums at the riskiest end of the market are fading.

“We think this emerging trend highlights just how much risk some investors are willing to take in the current environment,” analysts at Kroll Bond Rating Agency (KBRA) said in their midyear outlook report, cited by Bloomberg. The amounts of these B-rated slices that are being sold are still relatively small – $197 million were sold in the first half, according to KBRA – but that’s up from zero last year.

By contrast, in the broader bond market, the highest rated corporate bonds, AAA and AA, have seen their prices fall and their yields rise sharply since mid-2016. The chart below shows the average effective yield of AA-rated bonds, currently at 3.46%, up from the 2.1%-range in mid-2016 when the Fed was in its final throes of flip-flopping before it turned into a tightening machine:

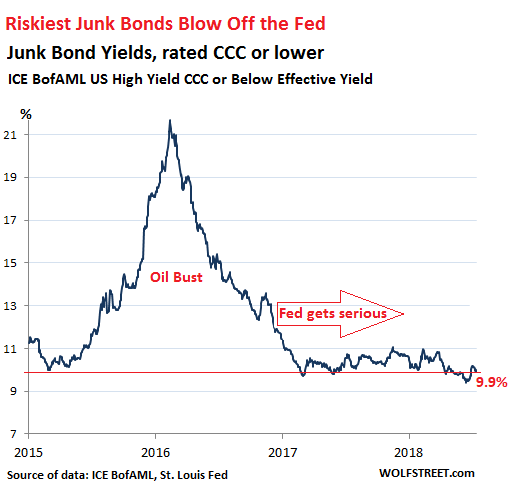

At the same time, prices of the lowest rated junk bonds, CCC-rated and below, have risen and yields have dropped. These bonds carry the highest credit risks, ranging from “substantial credit risk” to “default imminent with little prospect for recovery” (here’s my ratings cheat sheet for the three major US ratings agencies). The average effective yield of 9.92% is down half a percentage point from where it was a year ago, and down massively from 2016:

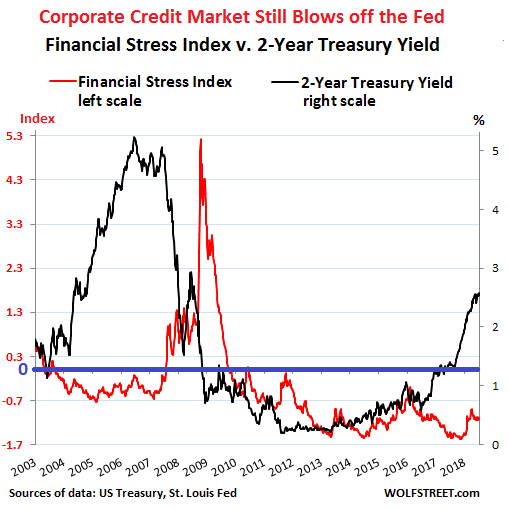

The Financial Stress Index, released weekly by the St. Louis Fed, tracks these sorts of developments – the “financial conditions” that companies face in the markets. The index reached record lows in November, indicating that there was extraordinarily little “financial stress” in the markets after years of ultra-easy monetary policies. The index then ticked up from January through March but has since started to revert to stress-free nirvana.

The index, which is made up of 18 components, is designed to show a level of zero for “normal” financial conditions. When financial conditions are tighter than normal, the index shows a positive value. When these conditions are easier than normal, the index is negative. It’s not a leading indicator. It just shows what’s going on in the credit markets right now.

But the two-year Treasury yield, which is very responsive to monetary policy, is a leading indicator of financial stress in the credit markets, but with a fairly long lead time. Its has spiked to 2.59%. It shows the direction in which the financial stress components – such as junk bond yields, spreads, and risk premiums – will move.

The chart below shows the two-year yield (black line, right scale) and the Financial Stress Index (red line, left scale). The horizontal blue line marks zero (neutral) for the Financial Stress Index. Note before the Financial Crisis, the lag of two years between the two-year yield that shot up in 2005 and 2006 as the Fed was raising rates and the Financial Stress Index that started shooting up in 2007:

The chart also shows the lag in the current cycle between the two-year yield, which has been rising higher since 2016, and the expected tightening of the financial conditions, a process that hasn’t really begun yet.

Broader markets are notoriously slow to react to a shift in monetary policies. But when they do finally react, the adjustments in asset prices, yields, and credit availability can be sudden and eye-popping, as amply demonstrated last time. This time, the Fed is hammering home the theme of “gradual,” in the hope that markets will adjust “gradually” over years, and not all of a sudden in an ugly moment of reality, as they had done during the Financial Crisis.

But that memo hasn’t reached the riskier parts of the market yet. And that riskiest end of the market is at greatest risk of a sudden adjustment – and given how loose the financial conditions still are, that adjustment at the riskiest end of the market could be a mind-blower – but hey, that’s why these investors are getting paid the higher yields now.

In the same vein, “reverse-yankee” junk bond issuance just hit a record. Read… NIRP Did It: I’m in Awe of How Central-Bank Policies Blind Investors to Risks

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Two points:

1. With the economy booming, the riskier parts of the economy seem less risky by now. Maybe these junky bond-issuers will actually be able to pay on time.

2. Everyone who buys this stuff knows it is risky. The only naive buyers are retail junk-bond fund holders. Everyone else has an exit plan and a hedging strategy. In conference rooms across the nation, white boards are covered with arrows and boxes – if this happens, then we do that. They’ve got interest rates swaps, they’ve got index puts, they’ll long the VIX.

Point 1 had better be true, because experience has show that it is impossible for everyone to exit a market at the same time, or transfer the losses to ‘someone else’ through hedging.

Since 2008, the Fed and its central bank accomplices have dramatically escalated their “No Billionaire Left Behind” monetary policies aimed at concentrating all wealth and power in the hands of a corrupt and venal .1% in the financial sector. I suspect a lot of the seemingly reckless behavior we see from the latter comes from the inside knowledge that the Keynesian fraudsters at the central banks have their backs no matter what, and our captured regulators and enforcers will turn a blind eye to even the most blatant market rigging and inside trading scams as long as their oligarch puppetmasters are the beneficiaries. As such, anyone who assumes that fundamentals or market forces will ultimately determine risk, does not grasp how completely rigged and manipulated these fraudulent “markets” have become.

“No Billionaires Left Behind”….

Oh, that’s good… I’m using that one. What you said in 4 words speaks volumes.

1. Its possible the economy isn’t booming, that the indicators are responding to increased borrowing costs (Fed raises interest rates)

2. What’s the difference between a promise and a lie?

Your points are good, boom is such an ugly word

While economic growth appears robust and a solid GDP number can result in a feel-good moment that builds consumer confidence it can also mask growing weakness in various parts of the economy. Quantity simply does not make up for poor quality, we are talking about two totally different animals.

The false narrative that simply growing the size of an economy even by using deficit spending undercuts the importance of a solid economic and the long-term stability of the financial system. The article below delves into poor investments.

In the meantime, the the 2 , 10 and 30 year, continue to come together…. All below 3%.

The Fed has zero credibility, along with a nine-year track record of enabling the most gargantuan asset bubbles and speculative manias in human history with its deranged money-printing and tsunami of “stimulus” for its bankster cohorts to gamble with wild abandon, with all losses transferred to the public ledger. Hence, Yield Chasers can be forgiven for assuming the financial crack cocaine will resume flowing into the markets at the slightest hint that the Fed’s Ponzi markets may be nearing implosion.

The Bank of Japan has had accomodating monetary policies in place since the Japanese government got cold feet in 1990 by watching the Bubble Economy implode and ordered the BoJ to reverse course.

Those accomodating policies, along with a government too often ready to turn the other way when it came to financial and accounting fraud, managed at very most to make the demise of financial zombie pirates such as Dai-Ichi Kangyo and Daiwa Bank a long and costly process instead of brief bankruptcy procedure. It has also made many of Japan’s much vaunted heavy industries and construction companies even more dependent on government contracts, which in turn depend on the Japanese government’s ability to keep on stacking bonds insides the Bank of Japan’s virtual vault. Just look at the nigh-on-unbelievable sums the Chuo-shinkansen is swallowing.

It may work in Japan, at least until they are managing to keep inflation somehow under control and their currency doesn’t come under attack, but can it work in countries like Italy and the US which seem to have serious problems even repairing railway bridges and resurfacing roads?

You are absolutely correct, the Fed has backstopped markets with fully guaranteed put insurance and they have infinite currency resources to pay off on the insurance. The cost of the insurance is a worthless currency – a price the Fed is willing to pay.

It is beyond obvious that any “tightening” cycle, now or in the future, is nothing but a short term blip within a much larger and permanent dollar devaluation and market participants are well aware that the riskiest thing they can do is hold cash in the face of the ongoing, massive, central bank dollar devaluation.

When Bernanke changed the official mandate of the Fed from currency stability to currency devaluation he created a steady flight away from the currency. Other central banks followed his direction and now investors are forced to buy any asset they can get for any price on offer.

We are not in an asset bubble era, we are in a currency devaluation era. There is a subtle difference, bubbles pop but devaluations only make assets look expensive. Assets never correct because the currency is dropping off a cliff to it’s inevitable death.

Anyone who paid 1000 marks for Bayer stock during the Weimar Germany era may have appeared to be paying an inflated price for the asset but in retrospect that person got a bargain and his wealth was tossed a preservation lifeline.

We have arrived at a time in history where the price you pay for an asset will never be too high – no matter what you pay in nominal terms.

This is the fear that is paralyzing my investment strategy: will the bubble deflate or will the absurd valuations be inflated away by currency devaluation.

I agree with all the comments I’ve read. All I can add to yours is that I would rather have not lived in Wiemar Germany and especially not the 30 years after that. What is better – hyperinflation or deflation. Wiemar Germany gave us Hitler. What would hyperinflation produce now? Argentina is surely a frightening state at the moment.

It is beyond obvious that any “tightening” cycle, now or in the future, is nothing but a short term blip within a much larger and permanent dollar devaluation and market participants are well aware that the riskiest thing they can do is hold cash in the face of the ongoing, massive, central bank dollar devaluation.

Fully agree. Moreover, it is obvious that the Fed’s financial sector cohorts appear to have their usual inside knowledge of the Fed’s next moves, which is why they’re blowing off the Fed’s “we’re really, really gonna pretend to be a responsible central bank and tighten now!” and are instead banking on a QE restart after a short-lived QT head-fake.

The yields will reverse higher when the central banking interest rate will rise above official inflation rate.

I would say unofficial interest rates, but that would imply fund managers read WS. /s

That is hard to achieve when the central banking figure heads are cheerleaders for inflation.

Everything is interconnected. This blog is intended for finance and related topics and comments, but the abnormally low rates in the US, at this time, are a reflection of the interconnections of so much of what is in the news today.

The bad guys are being challenged. Their sacred cows are being butchered. The 1% and above are regrouping.

It’s all about two things, money and ideology. I will keep my comment about money since it provides financing for all that ails the world. Particularly printed money and interest rates managed to abnormally low levels.

Perhaps a decade or more ago, some bright opportunists noticed that chumps rob banks. Smart people control central banks. Academia was nudged into believing, without question, weird theories about zero and negative interest rates and how they, when combined with unlimited printed money, could finance the world maybe forever at low to no cost. Economists who rejected those ideas are considered outcasts and unqualified.

NIRP and ZIRP along with an unstoppable printing press could finance governments or build asset bubbles. Or both. The only catch was everyone needed to do it at the same time with the same intensity. Otherwise capital will go to the best real return, not necessarily the highest bubbley return.

Bernanke and Yellen went along. The coming of Powell changed that and rates are normalizing, albeit slowly. Savings is no longer being consumed to support living expenses, but it’s yielding returns in the capital markets. Income is rising and the US economy is expanding as a result.

The 1% and above is unhappy about this as they feel they are losing control of what they believed was the coming of a sure thing for them. The worst influences from the new age of money that is now ending in the US are fighting tooth and nail to preserve their accomplishment. Thus, long rates are still low, for now, and yield chasers are going into junk credit because it’s either OPM or they think the fix is still in or they’re just not very bright. The recent hysteria in the world would support the ‘not very bright’ thesis. The louder the noise, the closer it comes to a resolution one way or another.

The sudden adjustment occurs because banks and other indebted companies have a tendency to hide bad news. When they see other companies report bad news, they are adequately camouflaged and all the bad news gets reported at once. The accounting rules allow companies and their purchased auditor firms the ability to apply “judgement” in many areas.

Isn’t it interesting how GE reported a sudden $6-8B increase to its reserves when new management took over?

“The longer the Fed’s strategy is not working, the longer the Fed will raise rates, and the higher the risks will be that, instead of working “gradually,” as the Fed always says, its strategy is going to work belatedly but all of a sudden – which would make for a brutal surprise.”

“Broader markets are notoriously slow to react to a shift in monetary policies. But when they do finally react, the adjustments in asset prices, yields, and credit availability can be sudden and eye-popping, as amply demonstrated last time. This time, the Fed is hammering home the theme of “gradual,” in the hope that markets will adjust “gradually” over years, and not all of a sudden in an ugly moment of reality, as they had done during the Financial Crisis.”

As of now the market does not believe the Fed and is thus cruising along. The irony is that should that ugly moment of reality, of market believing the Fed, arrive, the Fed may well wish the market had not as there will be nothing “gradual” about the inevitable repricing and it will take back all the hikes and QT and some. After all, while Goldman Sachs does God’s work, the central banksters do Atlas’s work and thus have to save the world. Hopefully people will see through this this time atleast and go for them!

This moment will arrive but I know not when.

So, is a good time to buy AAA and AA ABS?

The Fed is already concerned with managing its rate hike policy, (when is it time to back off?) I think again the market has 110% faith in the Fed, we raise a teeny bit and accommodate a whole lot. (ROW CB policy helps) The market here is being super-rational. The Fed may raise rates and do QE, “we’re sorry our rate hike policy impaired you bond portfolio, here give us some of that…” The result is more Fed induced financial distortions, quality bonds get hit, junk bonds rally – but that’s their MO. That chart of financial stress and yields? Are we heading for the inverse 2008 moment? What will that look like? They shoulda’ raised em’ then, and now they are stuck pulling rates through the looking glass.

Everyday I wake up and look forward to reading wolf. I truly think he has a better grasp of everything than anyone else I read. The only problem is by 9 am I realize nothing matters. Tomorrow is a new day, keep writing and I will keep reading. Thanks for everything.

There must be a lot of demand to keep long-term bond interest low in the face of the Fed’s tightening. So who is putting incremental buying pressure on these bonds?

My theory is that US treasuries see incremental demand from NIRP/ZIRP refugees from Europe and Japan. For that to change the EU would have to stop QE and start tightening. Not sure that the EU would survive such a change. Neither would Japan.

My take is get ready for a flat yield curve for the foreseeable future.

The world is awash in capital in search of a productive investment. This depresses long duration Treasury yields while pumping up equity valuations.

I disagree about the yield curve staying flat for the foreseeable future. The Fed has turned downright hawkish and will continue raising the FFR as long as it appears the raises are having little to no effect on the real economy. The long end of the curve will remained fixed around 3%, and an inversion will occur toward the end of this year, but earlier if there are any economic hiccups that move the long bond yield down in a substantial way.

We are right on the cusp of a major policy mistake at the Fed. They are already saying the yield curve doesn’t matter anymore and unconcerned about causing an inversion. My reading of the tea leaves is US recession late in 2019 to early 2020 if we stay on this course.

There have to be recessions. It was Greenspan avoiding the mere hint of one for 15 years that got the economy and the Fed in trouble.

Recessions used to be shallow and brief but when they are not allowed to correct excesses they build up into big ones.

Enter the ‘Greenspan Put’ about how he convinced folks up to 2008 that the Fed would never let asset prices incl house prices decline.

So they doubled down again and again.

Oddly, he has in a sort of round about way admitted he F567ed up.

The Fed is trying to engineer a ‘soft landing’ which if you are at 30, 000 feet, means you have to descend.

The trillion dollar, lunatic so- called tax cut hasn’t made it any easier.

(So called because it isn’t paid for. It’s just more debt.)

A gentle reminder: the future isn’t foreseeable. The present and the past are somewhat knowable.

Here is my dilemma, which one is a better investment right now, 2 year bill yielding 2.6% or 10 year note yielding 2.8%?

That’s the kind of question that can make someone’s head explode.

Are you serious or joking?

Do you know how to price a bond?

Do you understand the time value of money?

Do you suspect a sudden and unexpected decrease in rates?

Do you just see two numbers and something to idly ponder?

Do you understand that markets exist because of what people do and everyone tries to find an edge?

Do you understand that people lie, even those who look official and responsible, and that some lies are gargantuan and considered to be absolute truths by those who idly ponder or profit from those who idly ponder?

I guess I don’t understand why the retail investor wouldn’t buy a basket of, say, Ford, Philip Morris, and Verizon.

If you can leave the money ten years, chances are you can get your money back intact at some time in those ten years and you’ll earn a little north of 5% with those three if you divide your money between them.

Is it too much risk for someone near retirement?

That’s a good question, if in year 3 when the bill comes due the 2yr rate is 2% then the bill would provide nearly 1% over current yield. In 99 I got my mother out of stocks and we went into short term paper, while the 20yr was paying 5%.

I think you’re implying that the well disciplined and not political at all Fed with keep raising rates until the market ‘respects its authority”??

That’s not a bad assertion, but based on that chart of Stress index over 2 yr yield I don’t quite see the correlation. The lag seems to be many years and it could very well be that it would take many more years of 0.25% hikes to bring about an increase in market stress.

Or maybe the risk premiums rise when the markets correct, and the Feds hiking is only incidental. I’d say the Fed really really likes asset price appreciation and it won’t do anything to jeopardize it.

But the chart is useful, because if the Fed’s policy is raising rates, then it may have to do so for a longer period of time than many think.

Maybe the yields are kept low by funds returning home from the EM all at once.