Was “QQE” just a pretext for bringing the government bond market under control to avoid a Greek-style debt crisis?

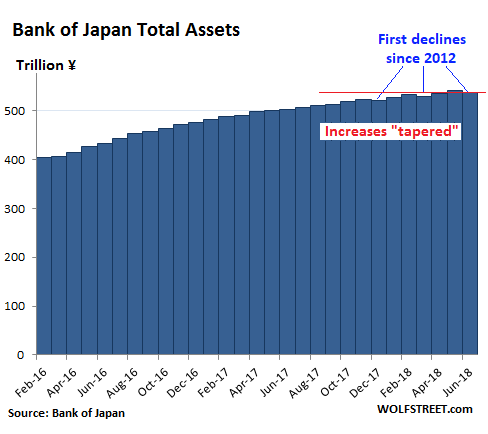

In June, total assets on the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet dropped by ¥3.79 trillion yen ($34 billion) from May, to ¥537 trillion ($4.87 trillion). It was the third month-over-month drop in seven months, and the first such drops since late 2012, when the Abenomics-designed blistering “QQE” (Qualitative and Quantitative Easing) kicked off. So has the “QQE Unwind” commenced?

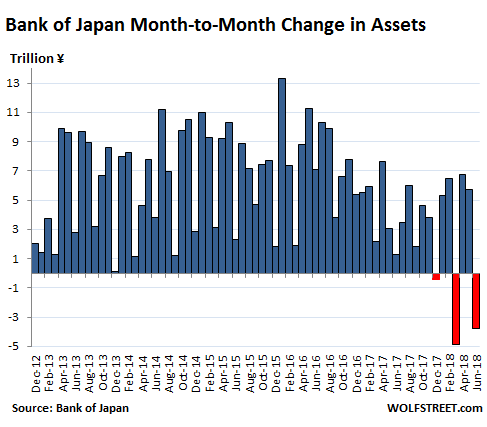

This chart shows the month-to-month changes of the total balance sheet. Note the trend over the past 16 months and the three “QQE unwind” episodes (red):

But this sporadic balance sheet reduction (here’s my report on the December decline) and the overall “tapering” of its growth contradict the official rhetoric.

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda along with most of his colleagues keep insisting that the BOJ would “patiently” maintain its ultra-easy monetary policy and that it would “keep expanding the monetary base until inflation is above 2%.” The blistering asset purchases would add about ¥80 trillion ($725 billion) to the balance sheet every year. And the BOJ has repeatedly affirmed its short-term interest-rate target of a negative -0.1%.

In September 2016, it introduced a new thingy that no other central bank has tried before: “Yield Curve Control” – a policy of targeting yields along the entire yield curve, and not just short-term yields. The stated purpose was to make sure the 10-year yield stayed near 0% but doesn’t drop into the negative, a concern at the time.

The BOJ has decided that it can control bond yields all the way up the yield curve by buying or selling long-dated Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs). And so far, the experiment in market control has worked. Along the way, the entire JGB market has withered, and there are days when trading dries up completely.

Under QQE, the BOJ has been buying mostly Japanese government securities (JGBs and short-term bills); it also purchased corporate bonds, Japanese REITs, and equity ETFs. But now, the party appears to be ending, despite the speeches to the contrary.

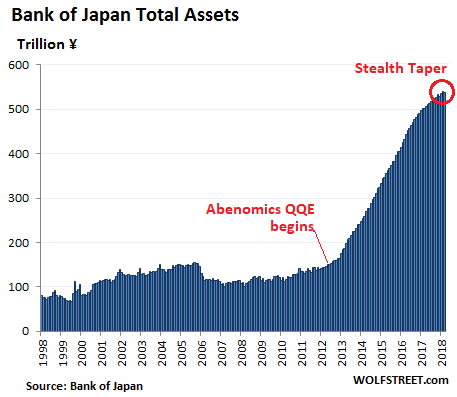

From the distance, however, the flattening out (tapering) of the BOJ’s assets is barely noticeable, given the magnitude of the whole pile that amounts to about 96% of Japan’s GDP (the Fed’s balance sheet amounted to about 23% of US GDP at the peak):

The leveling off of these monthly purchases becomes clearer in the chart below that covers a shorter time frame. Note the monthly declines in December, March, and June:

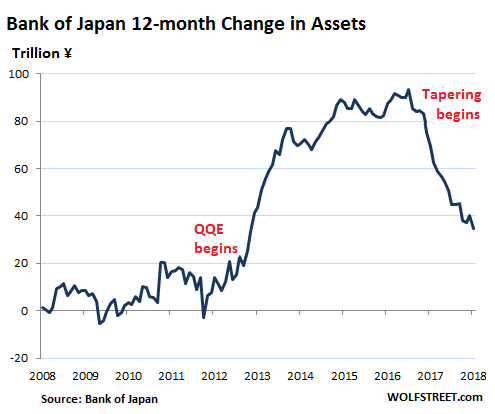

During peak QQE, in the 12-month period ended December 31, 2016, the BOJ added ¥93.4 trillion (about $846 billion) to its balance sheet. Over the 12-month period ended June 30, 2018, it added only ¥34.9 trillion to its balance sheet. That’s a 63% plunge from the peak.

This chart shows this rolling 12-month change in the balance sheet, going back to the Financial Crisis:

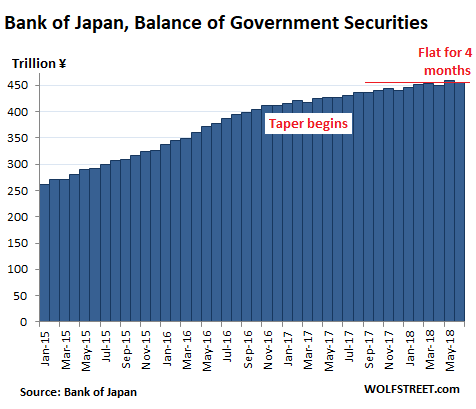

Japanese government securities (JGBs and short-term bills), are the largest asset class on the BOJ’s balance sheet. The BOJ holds 46% of all outstanding Japanese government debt, up from 14% in late 2012 before QQE kicked off. But the amount of these securities on the BOJ’s balance sheet fell in June by ¥4.6 trillion ($42 billion) from the prior month, to ¥454.8 trillion, the same level where they’d been in March.

It was the third monthly decline in seven months. For the 12-month period ended June 30, the BOJ added only ¥27.4 trillion of these securities, down from around ¥80 trillion during the QQE peak years.

In other words, the BOJ has started to let some government securities mature and roll off the balance sheet without replacement – much like the Fed’s QE unwind.

None of this was announced – neither the “tapering” that commenced 16 months ago nor the recent sporadic “QQE unwind.” They happened despite official rhetoric to the contrary.

The BOJ combined with government-controlled institutions such as the Government Pension Investment Fund, one of the largest such pension funds in the world, and the partially privatized Japan Post Bank, one of the largest deposit holders in the world, own a solid majority of the Japanese government debt and together totally control the market for it. But the private sector has largely exited the Japanese government bond market.

The BOJ’s mantra “to keep expanding the monetary base until inflation is above 2%” is an increasingly obvious pretext for a policy that was designed to avoid a Greek-style debt crisis.

This type of inflation, though low by US standards, would be devastating to Japanese consumers because nothing is prepared for inflation and nothing is indexed to inflation after more than two decades of relative price stability. At every uptick of inflation, consumers cut back because their incomes aren’t going up with inflation, and their savings aren’t earning anything, and their pensions aren’t going up either – and people who depend on savings and pensions are a big group of spenders in Japan.

The subtext is that authorities may be OK with low inflation and that this mantra of 2% inflation-at-all-costs is used as pretext for QQE to get the bond market under control preemptively by purchasing about half of all outstanding government debt – a policy that was formed after having watched what a debt crisis did to Greece.

Japan – by far the most over-indebted country in the world, far more indebted than Greece – has decided that whatever the outcome of this debt will be, there will be not debt crisis. There may be a currency crisis – which Japan is more able to weather – but there will be not even a hint of a debt crisis. And now that the bond market is entirely under control, bond purchases can be tapered away. And this would mark the end of QQE.

As far as reserve currencies is concerned, central banks are not enthusiastic about the Chinese renminbi. Read… US Dollar Hegemony Tripped Up by Chinese Renminbi?

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

“Japan – by far the most over-indebted country in the world, far more indebted than Greece”

Speaking of Qs, I don’t find that quantitative comparison useful, because of the qualitative difference that Japan is a sovereign currency issuer, whereas Greece forfeited that right – and engaged in some major Goldman Sachs-aided debt shell games – in order to join the EU and thereby doomed itself.

I used to believe Japan was screwed due to its massive government debt, but as long as the central bank can keep interest rates on same more or less at zero or even below, the amount really does look like a “who cares?” Whether the market distortions due to the relentless debt and other asset purchases are producing dangerous levels of real-economy-harming malinvestment is the more pertinent question. But comparing e.g. at levels of social safety nets, wealth inequality and society-fraying class warfare, Japanese citizens seem significantly better off on all fronts than Americans, despite the 2x-or-more-greater public debt. Perhaps the U.S. running deficits to support imperial warmongering all over the globe and bailouts of crooked oligarchs has something to do with that.

And on that note, I hope my fellow USians had an enjoyable July 4th holiday. :) Naked Capitalism re-ran an interesting post on the true origins of the holiday today.

Unrestrained power is the solution because markets

I agree! I doubt they will ever let short or long term interest rates go up and purchase and start up QQE again.

It still blows my mind we live in a corporate socialist economy in the developed world and the US citizenship is stupid enough to believe social programs that would be in their best interest and their piece of the pie is called dirty socialism.

Guess the masses aren’t smart enough to see the cards aren’t stacked in their favor.. While at least in Japan there is a bit more benefits being handed out to the average person.

Dirty Hippie Socialism? :) All I know is damn good jobs were off shored as we were being told it was good for the consumer and we didn’t want those menial (for irredeamables?) jobs anyway. Funded by taxpayers, even.

This was nothing less than special interest groups capturing the spread on labor arbitrage.

Irredeamables occupy!

Whatever the Japanese central bank does or does not, in the end the savings and/or the bond purchasing power of the Japanese will become worthless. Given zero interest rates, that is already the case.

Japan has few natural resources and has to import most of its commodities – and these will go dramatically up in price ( as yen ) causing Weimar type inflation within Japan.

hendrik1730,

Concerning your second paragraph: Japan is an export economy. It exports goods that are high up on the value chain but imports cheap commodities. This generates a large amount of foreign exchange for Japan that it can use to purchase imports. As long as it runs a trade surplus, the scenario you cite won’t happen.

Argentina is an example in the other direction and is in the sort of scenario you describe. It exports cheap commodities, imports goods up high on the value chain, and runs a trade deficit. It doesn’t have the hard currency to support its own currency.

Japan is a nation of productive savers (they taught Americans how to design and build modern vehicles). The old folks have savings accounts at the post office and pensions that are invested in JGB – the rest of the sizeable government deficit spending is being monetized by their central bank. The old people are not afraid to hold their savings in Yen currency because inflation has been stable and if it flairs up they know the youngsters will take care of them because of culture and duty. So the whole thing has worked up to this point – but they have made indentured servants of the younger generation.

On the other hand, when the dollar crisis hits our younger generation feels no such cultural obligation and they will not agree to indentured servitude to pay your Miami condo fees. Be sure to keep your wealth in something productive, if you don’t you will not be happy.

ewmayer,

A 10-year JGB yield of 3% would be the definition of a debt crisis in Japan, given the government’s level of indebtedness. In 2012, there were fears that the private sector is unreliable, even in Japan, and might decide to suddenly walk away, as it did in Greece. Then the BOJ would have had to step in on an emergency basis to deal with the crisis. That I think was the fear.

But that’s where the parallels with Greece end because the central bank of Greece couldn’t do that, and instead Greece had to beg the ECB to do that — which came with the infamous conditions.

Japan is a major global creditor (like Germany where the government also has borrowings) and not a debtor. Their own citizens hold most of the debt and are the world champion savers.

They maintain a positive trade balance with the rest of the world which increases the national equity every year, a large portion of which finances the national budget……It is (and has been) sustainable… at least until the trade balance reverses… a la Argentina.

Yes, see my reply to Kent earlier today at 7:58 AM (further down).

The inflation event will be non-linear. For the longest time it will look like inflation is tame, then all of sudden a conflagration will ensue.

My thoughts too. Quite astonishing how despite decades of money printing prices in Japan have been somewhat stable, or from our perspective actually decreasing considerably. Holidays in Japan are now quite affordable as opposed to say 15 year ago.

Perhaps culture plays a big role with extreme social cohesion in Japan preventing people to adapt behaviour.

At some point a reckoning will be inevitable, likely via a landslide rather than gently approaching the 2% inflation “target”.

Wow that’s such a Japanese solution. Convince the non-controlled buyers to exit, the remaining govt-controlled buyers won’t sell, and thus there will never, ever be a debt crisis. And pretend you’re doing something else in the meantime.

Great analysis – and reminder: we tend to think that Japan operates under the same rules as the US, just with a little soy-sauce flavoring. They really do not.

The search for a monetary philosopher’s stone that can change debt into wealth is as ancient as money itself. For example, circa 400 BC, Dionysius the Elder tried to stamp 1 drachma coins with a 2 in order to pay off the state debt.

As the millennia have rolled by, every attempt to create a monetary philosopher’s stone has failed. But contemporaries hail these schemes as successes during the brief window that always exists between monetary action and economic consequence.

We are living in one of those windows right now. And the results will be the same.

And the window is critical to ensure that the strong who created the debt walk away with the wealth and leave the debt on the weak, who had to give up their wealth.

Wolf, any thoughts on why expanding the monetary base hasn’t lead to substantial inflation in Japan?

Hopefully you had a good 4th and are sound asleep out on the left coast as I type this…

Kent,

Many people have been scratching their heads about this. And I don’t have any solid answers either, but I’ll throw out some thoughts here.

Consumer price inflation — and I think that’s what you’re talking about — is a very complex phenomenon. A lot of it has to do with confidence and expectations. Then there’s the issue of income: if household incomes are flat or declining, including income from savings and pensions, it’s hard for price increases to stick because consumers are picky about prices. Expanding the monetary base is only one of many factors that might cause inflation.

Japan is a scary model of how far things can get pushed under highly controlled circumstances, and for how long this can be maintained, until suddenly something goes out of control.

Japan is also very unique. It’s an insular economy with an insular mindset. The government is not fond of free markets. Very little immigration and low birthrates lead to a declining labor force, but increased automation leads to rising production, much of it for export. Real wages have declined over the past 25 years (from very high levels at the time). The trade surplus and the large amount of foreign exchange reserves are a huge plus for the stability of the currency.

Imports are controlled by administrative procedures, so in many aspects Japan has always been fairly expensive and deals with regularly occurring things like “butter shortages” – when local producers cannot keep up for some reason (heatwave causes cows to produce less milk, or whatever) and imports cannot get into the country. We laugh about these things because they seem silly, but in an economy such as Japan’s that’s one of the side effects.

Here is my thoughts based on watching Ray Dalio’s “Machine”. There are 3 kinda of transactions, goods, services and financial assets. The “Inflation” defined as rising price of the same currency units on “goods” and “services” can be managed, manipulated in the following way. If you expands supply of goods and services faster than expansion of demand, price will be stable. Citizens do NOT get a universal increase in pay check, while a lot of businesses gets started producing goods and services. This will lead to lower profit for producers and some times loss. So there comes in zero interest rate. Businesses do NOT care about losing money since they can always borrow tomorrow to pay back yesterday with zero cost. This gives the “confidence” to produce to add supply indefinitely. Yes all the jobs creased in money losing business expands demand as well, so as long as supply is added more than demand, this balance will NOT go haywire. The end result is expanded debt on all kinds of balance sheet, but as long as interest rate zero, the time horizon in the future is always infinite.

How can this balance be broken? The same old human nature of eating each other’s lunch. If Japan has internal conflicts between political parties and some one wants to move his own agenda at the cost of everybody else, then he will lit a match on this pile of powder. But Japan is NOT such a country. You can see that when Fukushima happens ed. Everything stays cohesive and move orderly even when citizens are under nuclear

radiation. That’s the power of Japan “culture”.

That any government agency or person or group, directly or indirectly , should seek to deliberately create inflation should be a sure sign of evil intent to undermine the health, stability, and well being of the people.

For people to go along with the idea, the concept, as if a good thing, is pure stupidity, if not insanity.

There is always a price for the public to pay for turning a blind eye.

If you want to see the damage of inflation, go buy a pound of rice in Japan. In the US, rice is 2 to2.5 times higher in 8 years, pasta is too. The damage from inflation is not diminished by quoting a 2% target (as if life works that way.)

Faith, Japan has some of the heaviest agricultural subsidies in the world despite just 4% of its population being dependent on agriculture for their livelihood (it’s 5% in the US and 8% in the EU by comparison).

Last time I checked the Japanese government was spending Y7.2 trillion/year (more than US$65 billion/year) on direct subsidies. By comparison the EU spends about €40 billion/year on direct subsidies. I won’t even get into indirect subsidies, such as those passed to sugar mills because I seriously risk getting sick, and my grandfather was a farmer and I worked myself there.

Fishing subsidies are another entirely different can of worm.

This means foodstuff is heavily subsidized, especially staples such as rice, soy, pork, milk, watermelons etc.

In return for these subsidies farmers, brokers, distributors etc agree to keep food prices as stable as possible, a huge bonus in a country like Japan, where wages and pensions have no built-in mechanism to keep up with even mild inflation. As Wolf always says Japan is not a free market. It has never been.

The US are one of the world’s largest rice growers and boast the world’s foremost rice growing company, Riceland Inc. But Riceland is chiefly geared towards turning a profit and does so by exporting the bulk of its production.

Rice is not as heavily subsidized as corn and cotton in the US, but it’s subsidized nonetheless, albeit the justification for this is logical: the ridiculously generous subsidies some other rice exporters pay to their growers.

To quote but two examples, between 2011 and 2014 the Thai government bought rice from growers at the much inflated price of $450/ton then, when warehouses started to fill up, dumped it on export markets at $350/ton or even less. This caused a budget crisis which in turn sparked a political crisis.

Vietnam has put in place a “price floor” of $236/ton for rice: this means that if prices fall below this threshold, the government steps in and buys rice to reinflate its price, a system it copied from the EU’s infamous “butter mountains” system but with a chief difference: all rice thus bought must be exported to avoid distorting pricing at home.

I wanted to get into the agri business in the days, but ended up studying chemistry at the Uni and these days I mostly concern myself with heavy machinery… life has been strange, albeit not as strange as economics are!

Japanese grown rice is different than US grown rice.

It tastes different and cooks different.

It tastes different when you freeze it and then thaw and reheat it to eat it.

Just as Japanese wagyu tastes different than US ‘wagyu’.

Japanese will not eat American grown rice unless there is no alternative regardless of the cost.

riceboy,

Japanese-style rice is grown in California. You can buy for example Homai rice in 50-pound bags, as the Japanese buy rice in large quantities. There are a several different Japanese-style rice varieties, grown in California. Occasionally we get freshly harvested rise from my in-law’s family. One of mama-san’s sisters still operates the family farm near Hiroshima. And when they have a fresh harvest, occasionally we get some. But for the rest, we buy Japanese-style rice in 50-pound bags, grown in California.

The Japanese who live here eat it all the time. It’s just that Japanese-style rice cannot be exported to Japan because Japan won’t let it in.

I would launch myself in a long and mostly incoherent rant on commercial and heirloom cultivars and the little known basic difference between Indica and Japanica/Sinica groups (hint: it’s not due to geography) but I am need to edit the second half of my latest piece before. It reads like it has been written by an alien from Zeta Reticuli with only a rudimentary grasp of human languages… mercifully I read it again yesterday evening before mailing it!

When the US tapers, everybody has to taper or their currencies go out of whack.

Central bank monetary expansion is just a small fraction of the money creation that took place pre-2008. But back then it was the banks that were going hog crazy with financial practices that eventually brought about the great financial crisis. What the central banks think of as monetary expansion is nothing compared to what the banks did before. That’s why inflation targets are such a bad joke, especially in Japan. The BofJ is nothing but the government agency whose job is to keep the yen weak in order to subsidize exporters. Inflation targets are just the cover story that a mercantilist country uses to try to fool the rest of the world.

The really funny part is everyone is still expecting inflation.

The big taper jobs coming by the Swiss, the US, and Japan seem to auger a lot more deflation in asset prices, which no one seems to be anticipating.

A return to real interest rates will happen, but over a very long horizon- I would guess the next 5 to 10 years.

Of course, this just might hurt a lot of people counting on asset inflation to fund their retirements, but so be it.

As for the inflation hounds, show me the growing populations with burgeoning demands for housing in the US- only the chinese asset prop job and the crazy hot tech cities keep growing to the moon.

As for investors, good luck buttercup, so much looks peaked.

Someday this war’s gonna end…

I think the treasuries coming very close to inverting indicates you are not alone.

About a week ago CSPAN aired a banker conference at which Powell and a Bank of Japan person spoke(probably the chairman). I wasn’t paying too much attention until the BOJ guy said their low interest rate policy had not worked to stimulate the economy. He said the only thing currently stimulating the economy was a rise in wages, which is what got my attention. I think he also said he expected to meet the 2% inflation target by letting wages continue to rise. So much for QE.

Same situation in the US. Wage inflation is working, though mainly in the service sector where unions are not strong (teachers?) and with service contractors who can negotiate better than the large service unions. Not sure how much unions figure in the Japanese economy, where when things get tough everyone falls on their sword. The future for Asia brings into question the bubble of central authority in China, and the bubble of zenophobic economic and immigration policy in Japan. How can you be open on trade and closed on immigration?

Japan is very good at ignoring things or pretending something is not happening for the sake of “normality” aka saving face.

Rise in wages causing a 2% inflation is like pushing on a string: an economist wishful thinking. A reckless expansion of credit is a much better tool to cause inflation.

On that note, how is it that currency debasement is a central banking policy rather than a bad accident, and noone seems to question it.

How long can this dystopian economy continue?

I think home prices will come down because of the loss of the mortgage interest deduction on taxes, Fed is trying to raise rates which will lower the qualifying buying pool, Congress wants to increase the flood insurance rates, and some with adjustable mortgage rates may be forced to sell.

Homes in my neighborhood are now valued at 250% over their prices 30 years ago, while wages have not even been close to that climb.

Having a 30 year mortgage is going to be more risky in this rapidly changing working environment. Any bad year and the bank owns it.

Compensation $15/hr. PhD Strongly preferred.

Being new to your planet, I’m still unclear about one thing. When you talk about free-market capitalism, which type of government controlled centrally-planned system do you mean? China? The EU? Japan? The US?

Frankly, it’s a bit confusing.

Crony capitalism? Take your pick :-]