The Italian Dilemma.

By Caroline Gray, Senior Economics Editor, Focus Economics

The sudden panic about a potentially imminent Italian banking sector collapse back in July has somewhat subsided for now, but sooner or later the issue will inevitably rear its ugly head again.

Two months after Italian bank stocks collapsed even further in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, fears of an imminent need for a bail-in have receded as the Italian government works on plans to shore up its weakest bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS). This will be achieved via an alternative but rather ambitious method culminating, if all goes according to plan, in a new capital injection.

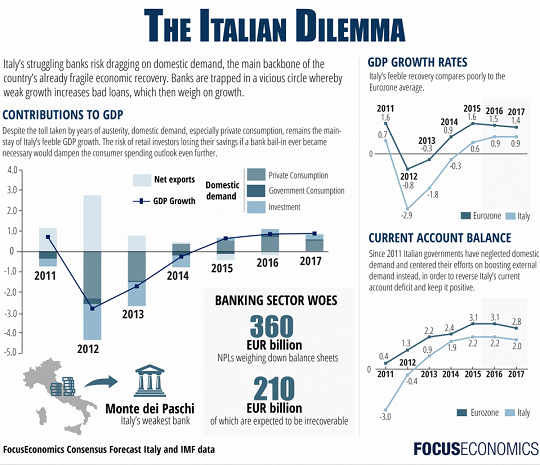

However, MPS, which came up short in July’s ECB stress tests, has already received capital injections in the past. Such plans to patch up banks have tended to involve kicking the can down the road rather than providing a more definitive solution to the 360 EUR billion of non-performing loans (NPLs) weighing down Italy’s banking sector – equivalent to one fifth of its GDP.

If a sustainable solution is not found to clean up Italian bank balance sheets in the near future, they will inevitably constrain domestic demand and thereby weigh on the country’s already feeble growth even further (click to enlarge).

Domestic demand, the longstanding mainstay of the Italian economy, is already under intense pressure. In the second quarter, GDP failed to grow in quarter-on-quarter terms, primarily on the back of a broad-based deterioration in all components of domestic demand (private consumption, government consumption and fixed investment). Domestic demand is expected to remain weak, based on our latest September Consensus Forecast for Italy.

A failure to swiftly clean up bank balance sheets means domestic demand will inevitably suffer as bank credit supply constraints continue to prevent the recovery of investment. Loan-loss provisioning reduces the credit banks have available for lending, especially to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and consumers, which are perceived as risky.

Analysts assessing the Italian banking sector are now most worried about the risk of chronically constrained growth rather than another systemic shock, as banks are trapped in a vicious circle whereby poor economic growth means bad loans keep growing, which in turn weigh on growth even further.

The latest ECB stress tests showed that most Italian banks do have loss-absorbing capacity to withstand a theoretical three-year economic shock, but strong concerns remain about their profitability as NPLs reduce their lending ability and deter investors.

Moreover, this scenario of sustained weakness prolongs the risk of banks eventually being forced to resort to a bail-in. A recapitalization of the banking sector involving substantial losses for retail investors would strongly hit consumer confidence and spending, the backbone of Italy‘s economy.

For a country whose already weak economic growth is heavily dependent on domestic demand, this would therefore bode disaster – and not only for the individual citizens with affected bond holdings.

Italy’s banking sector woes

The Italian government is desperate to avoid any bail-in, especially after the politically disastrous bail-ins of a handful of small regional banks last year.

In this context, it has sought to reassure the markets that individual critical cases of weakness are contained and new capital can be raised without the need for individual investors to take a hit. But exactly how the overwhelming quantity of NPLs in the Italian banking sector will be dealt with is still far from clear. Italian banks have only made provisions to cover just under half of the €360 EUR billion NPLs weighing down their bank balance sheets, of which €201 billion are already estimated by the IMF to be bad loans that will be irrecoverable.

Plans such as that affecting MPS, where NPLs are to be offloaded into a securitization vehicle in an attempt to sell them to investors, would seem to be in line with the IMF’s recommendation that Italy build a robust market in NPLs. And yet many analysts consider such ambitions rather wishful thinking, especially since most of the bad loans on Italian bank balance sheets are uncollateralized loans to small businesses and consumers (in contrast to the mortgage NPLs that dominated Spanish and Irish bank balance sheets during their time of stress), and specialist NPL buyers tend to be more attracted to loans with easily recoverable, tangible collateral.

Moreover, if Italy is to create a functioning NPL market, banks will need to accept significant write-downs on their loans compared to their current book value. There is a sizable discrepancy between banks’ valuations of the NPLs and the price they would get for them if they attempted to sell off the loans to specialist distressed debt players, which will create yet more of a gaping hole on bank balance sheets.

The small private Atlante fund and its successor Atlante 2, set up by the Italian government to help participate in distressed banks’ recapitalization and also to buy NPLs from banks, are unlikely to be anywhere near large enough to resolve these problems.

To complicate matters further, holdings of bank bonds by retail investors are exceptionally high due to the longstanding practice in the country of selling (or rather mis-selling) bank bonds to ordinary citizens.

An IMF report published back in July calculated that retail investors own about one third of around €600 billion of senior bank bonds and nearly half of an estimated €60 billion of subordinated bonds on the balance sheets of Italy’s 15 largest banks. Under the bail-in requirement of the EU’s Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) in force since the start of this year, at least 8% of a failing bank’s total liabilities must be written off before state aid can be requested, if the EU enforces strict adherence to the rules, though the Italian government has been investigating every possible loophole in case.

In Italy, the IMF estimates that this requirement would hit the majority of subordinated bond holdings by retail investors in the fifteen largest banks and that it would also hit some of their senior debt holdings in two thirds of those cases.

After the experiences of massive publically-funded bank bailouts in countries such as the UK, Ireland and Spain during the height of the financial crisis, the whole idea behind the BRRD was to break the link between banking and sovereign risk and to stop putting taxpayers on the hook for private banking sector failures, making bank bondholders pay instead. But this assumes that the bondholders are institutional investors, and fails to take account of the specific circumstances of countries such as Italy where retail investors risk having their holdings wiped out too.

In Italy’s case, many of the bank bondholders at risk are ordinary citizens and taxpayers, who were mis-sold bank debt as if it were as safe as placing their money in a savings account but with the added benefit of a much higher interest rate. In fact, retail investors are likely to be disproportionately affected compared to institutional investors, since individual citizens are usually sold more risky subordinated debt rather than its safer senior counterpart.

Reviving the risk of recession?

Unless concrete plans for how to create a functioning NPL market are devised, it is unclear how banks that need to recapitalize will be able to do so without ultimately ending up hurting at least some of their equity and subordinated debt holders. For a country where consumer spending is the cornerstone of an already weak recovery, imposing losses on retail investors, if they are not somehow exempted, would risk dampening consumer confidence to the extent that this could in itself push the country back into recession.

This is before the wider downside risk implications of a struggling banking sector are even taken into consideration. Even if a bail-in remains avoidable, if banks are forced to use their own precious reserves to increase loan-loss provisions and capital buffers in the absence of any substantial state aid injection, this risks prolonging the Catch-22 of poor growth leading to a weak banking sector and vice versa. By Caroline Gray, Focus Economics.

With a stagnating economy, even supposedly good debt on banks’ books may end up putrefying. Read… Italian Banking Crisis Turns into Mission Impossible

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

“The latest ECB stress tests showed that most Italian banks do have loss-absorbing capacity to withstand a theoretical three-year economic shock…”

Amidst all this handwringing that sentence seemingly takes every worry off the table. And yet, “the Italian government has been investigating every possible loophole” to avoid a taxpayer bail-in. But I thought, the stress test demonstrated….

The Italian banks are dead ducks. Dead. Ducks. They are, however, positively kinetic compared to the Deutsche Bank. It is now a sinkhole, not a bank, a repository for financial offal, a toilet that is now backing up and will mire us all in its derivative sewage. Plumbers are expensive.

Here’s the happy ending every banker hopes for: while, yes, everyone has gone to hell we should feel better because there are those who sizzle even deeper down than us.

It is well to remember that not all problems have solutions, and most dramas don’t have happy endings. However this plays out, it will have a severe and lasting impact on the Italian socioeconomy/culture.

The extent to which this financial crisis is the result of looting the banks and other productive enterprises by “organized crime” is unknown. If this is significant, no correction is possible, as any “assets” will quickly disappear.

Assuming that “organized crime” can be restricted to tolerable limits, one possible solution is for the banks, under the sponsorship/oversight of the government to form a consortium to examine the economic sectors, one at a time, access the viability and prognosis of the sector, their total loan exposure, and either liquidate those loans/organizations with no possibility of recovery, or alternatively to force amalgamation of the producers in the [potentially] viable sectors, restructure/write-down the “pooled” loans, and provide not only the necessary working capital, but close and constant oversight of their operations, forcing modernization of their machines, methods, and personnel policies.

One legal change that should be of help in both Italy and the US. is the enactment of a law (with severe criminal penalties) prohibiting “Trading while insolvent” (anti-zombi law). This seems to have had mostly positive effects in the countries which have enacted such statutes such as the UK, and several other Commonwealth countries. The “big stick” is that the corporate directors become personally liable for corporate debts incurred after corporate insolvency.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trading_while_insolvent

Easiest way to rob a bank is to own one. And white-collar crime, in Italy as well as the U.S., is practically unenforced, essentially because the pirates run the government. Banks didn’t have these problems when they were regulated, but then, what would be in it for the pirates?

All too easy to understand when you look at the root causes. But articles like these typically prefer to whine about the symptoms because that enables discussions about bailouts, bailins, and other ways to subsidize the pirates. Solving the problem by addressing the root causes simply wouldn’t enrich the wealthy at the expense of the general population.

Another doom and gloom on Italy meaning …. nothing will happen.

It’s actually quite amazing how resilient the various economies have become. In the old days, things would just collapse pronto, but now …

“…. nothing will happen.”

I’m not so sure.

QE, QQE, ZIRP, NIRP…. emergency measures designed to keep a financial system from collapsing … and they’re doing it, while creating ever bigger problems in the process.

Were mom and pop mis-sold those bonds or were they tempted by the yield so much so that they were blind to the risks?

I’m sure it’s all in the fine print…after all, those high priced lawyers need to earn their keep.

The politicians are scared for their necks and probably awake at night in a cold sweat amid visions of pitchforks and torches. It’s not their fault but they will be blamed.

Yep, greed on both sides of the table.

“The politicians are scared for their necks and probably awake at night in a cold sweat amid visions of pitchforks and torches. It’s not their fault but they will be blamed.”

Politicians write the laws and enforce the laws in such a way as to enable the piracy on the part of banksters. But naturally they have nothing to do with it.

Banks are highly incentivized to make bad loans, and are then flabbergasted when the loans go bad. Hoocoodanode?

A bad loan at 0.1% is just as bad as a bad loan at 5%, a concept which somehow completely escapes the comprehension of central banksters.

Create a security out of securities in default. I remember when this was fraud, but I digress.

only if it dosent clearly state, that the underlying assets, are in default.

I remember when fraud was a crime, and not a best practice.

I fair portion of these bad loans were made to keep unprofitable businesses afloat and kick the consequences down the road. I worked with a decades old family manufacturing business that simply could not make a profit based on their cost structure. Bank loans and government loans carried the company for years until the music stopped. The monies paid for payroll to hard working families and other normal business expenses. The end result is the same as if the money was “criminally” obtained. The debt is still there but there is no collateral and no ability to repay.

80% of bank lending goes into real estate in the US (blowing bubbles).

Productive lending is something banks avoid like the plague.

Don’t worry about them and count your lucky stars they can’t blow any stupid bubbles.