Bonds had a phenomenal run after 1981. At the time, the 30-year Treasury yield was 15%, inflation was running very hot, and no one wanted to buy bonds, fearing that inflation would wipe out the bonds’ purchasing power, unless they were compensated with a fat yield. Whoever took the plunge with 30-year Treasuries would be in for an awesome ride.

Treasuries – deemed a “risk free” asset, in terms of credit risk – are considered a conservative low-return investment. And yet…

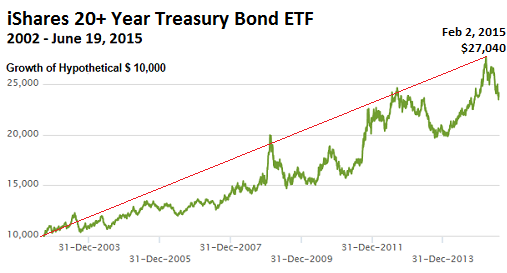

This chart shows the gains of a hypothetical $10,000 investment made in the iShares Treasury Bond ETF with maturities of 20 years or more, beginning August 2002. By February 3 this year, that investment had ballooned by 170% to $27,041:

This sort of thing has been going on since 1981, with some hiccups in between: a secular bull market in government bonds that lasted over three decades, despite several periods of rising interest rates and temporary negative bond market performance.

But then, earlier this year, something happened. Bonds came down hard, hedge funds were all over them, and the mood changed.

“We’re entering a bear market in fixed income,” Michael Novogratz, principal at Fortress Investment Group, told Bloomberg at the SkyBridge Alternatives Conference in Las Vegas in early May. “It’s time to get off the train and stay off the train,” he said, loudly talking his book. “We’ve seen probably a low yield in 30-year Treasuries.”

But the transition from bull market to bear market won’t have a major impact on stocks and bonds until the Fed actually begins to raise rates, he said. By that time, the bond-market swoon was well under way, particularly in euro bonds, and most particularly in German government bonds which were plunging from their ludicrous heights reached in mid-April.

Take it with a grain of salt? During his presentation at the conference, he also hyped opportunities in Chinese stocks. Alas, they just suffered their worst week since 2008. They’ve now gotten hammered down 13.5% from their peak earlier in June and are nearly back where they were when Novogratz was touting them. We’ll have to see how this trade is going to work out for him.

But he did hit a sore point: in his presentation, he also said that the Fed’s monetary stimulus, asset prices, and the debt-to-GDP ratio were all at all-time highs. A worrisome trifecta for bonds.

Yet so far, the Fed is still issuing its cacophony about raising rates, rather than actually raising them. But when it does accomplish this heroic feat, it would be the first time since 2006. For Novogratz, that’s when the bond bear market will kick off in earnest. Others chimed in with similar tunes.

But what’s a bear market in fixed income? Allianz, the owner of PIMCO, which runs the second-largest bond mutual fund in the world, defines a bond bear market this way:

Contrary to stock markets, there is no common understanding as to what constitutes a bond bear market. While a market correction of 20 % or more is labelled a bear market for equities, comparable definitions for bonds are often related to the magnitude of interest rate increases or central bank rate cycles.

In contrast, we have chosen a performance based definition in order to take into account the current yield level and its dampening effect on rising rates over the course of a bear market.

In this context, we define bond bear markets as episodes with negative 6-month nominal market return.

And this is what we have so far, in the sixth month of the year 2015: negative market return.

This chart of global government bonds in local currency shows the year-over-year percentage change in total returns. Since 1986 there were only 4 years with negative total returns, of which 1994 was the worst at -4%. So far, 2015 is the second worst at -3.9%.

Other bonds have gotten hammered too, with overall global fixed income down 2.9%: quasi-government bonds -3.8%; investment-grade corporate bonds -2.7%; and Emerging Markets government bonds -0.8%. But junk bonds – drum roll – are up 2.5%. They’d suffered a bad sell-off late last year when energy-related junk bonds got massacred. After a strong first half in 2014, junk bonds ended the year down -0.1%, as the only category in that group last year not to book a gain.

And if the Fed actually raises rates later this year, or perhaps even twice, as some intrepid souls like San Francisco Fed President John Williams expect (with some big IFs), then the bond bear market, based on how Novogratz sees it, might take on ugly proportions.

In the US, there are some real reasons to fret about bonds. And these are still the good times. Read… Wave of Defaults, Bankruptcies Spook Bond Investors

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

In the very long run this has to unwind, but in the short and intermediate term, maybe not so much. I used to think zero was the lower boundary for rates but Europe has shown that if you distort enough you can crack that barrier.

As rates rise:

1. Dollar denominated EM debt will be compromised as the DXY rises and there will be debt deflation and defaults.

2. The artificial stock market gains from low-interest-rate-fueled buybacks will unwind.

3. Margin-debt-fueled stock speculation will decrease.

4. Real estate prices will fall.

4. As stock values unwind, the decreased value of the repurchased shares will impair the companies that goosed their share value this way.

Dropping equity and real estate markets could easily offset the effects of rising rates on bonds.

The Fed is now like a basketball player who stopped dribbling and now can only pivot in place.

There is one solution to this mess and it has always been the only solution: debt deflation. Write off the bad debt once and for all. The Fed can’t do that. I think it’s done what it’s done in recent years because although Bernanke knew that monetary intervention wasn’t the solution, it was all he could do in the absence of realistic fiscal policy.

Obama made debt writedowns one of his campaign promises but once elected he reneged on his promise and decided instead to bail out the banks. If he had focused on this instead of the ACA he could have achieved greatness. Instead he went the Jimmy Carter route – prioritizing an agenda that had little immediacy (in Carter’s case it was energy independence – how’d that work out?) and relegating an impaired economy to the back seat.

I the meantime I’d rather lend money to the US than any other country. Do you want to lend to the US for 10 years at 2.3% or to Italy and Spain for less, and Japan for far less?

Bond bull for now.

What the establishment offers is simply PR …

Finance & Co. has been vigorously promoting the idea that our ‘con-omy’ is ‘back to normal’ and that our various structural problems have been ‘solved’ by way of our incredible cleverness and ‘technology. These problems being human/machine/livestock overpopulation (there are always more), resource constraints (there is always less) and the inability of our precious industry to exist without the ongoing credit stipend:

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?g=1j92

This is my favorite chart: it shows the relationship between debt and what is supposed to retire it over time: our self-deluding false narrative in two lines.

Of course bond prices are declining. We are at a Minsky Moment; where our entire borrowing capacity is turned toward servicing what we have accumulated. There are more risks than rewards = bond prices decline.

Total debt isn’t the issue. It’s cash flow to service the interest. Multiply total credit by some benchmark rate and watch your chart collapse.