The fiasco that is playing out in the natural gas industry doesn’t happen often in a free market, and when it does happen, it’s usually short—and brutal for all involved: namely, prices that are way below production costs. In most industries, hedging strategies might get market participants through the period, while unhedged production, a money-losing activity, gets slashed. If it lasts long enough, it causes a shakeout where less efficient or poorly capitalized producers, and their investors, get wiped out. It’s all part of the capitalist system that weeds out weaker elements through occasional sweeps of creative destruction.

As shortages crop up on the horizon, prices return to sustainable levels, and occasionally spike to once again unsustainable levels. For the survivors, or for lucky new entrants, the next step in the cycle has begun.

Alas, thanks to the Fed’s zero-interest-rate policy and the trillions it has handed over to its cronies since late 2008, the sweeps of creative destruction have broken down. Instead, boundless sums of money have been searching for a place to go, and they’re chasing yield when there is none, and so they’re taking risks, any kind of risks, in their vain battle to come out ahead. The result is a stunning misallocation of capital to the tune of tens of billions of dollars to an economic activity—drilling for dry natural gas—that has been highly unprofitable for years. It’s where money has gone to die. What’s left is debt, and wells that will never produce enough to make their investors whole.

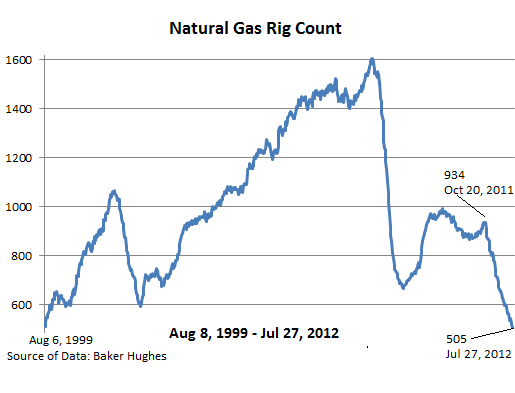

But the money has dried up. And drilling for natural gas is collapsing. Last week, there were only 562 rigs drilling for dry natural gas—the lowest number since September 1999. A dizzying downward trajectory:

Producers, if at all possible, are switching to drilling for oil and natural gas liquids (priced like oil), still a profitable activity. Thus, capital is now being channeled to where it can make money. Drilling for dry natural gas will continue to decline as the long delayed sweep of creative destruction is scouring the industry.

The largest producer, ExxonMobil, given its monumental size and worldwide focus on oil, will weather the fallout just fine. But the second largest producer, Chesapeake Energy, is struggling. It’s trying to dump assets to raise cash to deal with its mountain of decomposing debt. Other producers that haven’t diversified away from dry natural gas are in a similar quandary. And at current prices, it’s going to be bloody.

At $2.53 per million Btu at the Henry Hub, the price of natural gas is up 33% from the April low of $1.90 per million Btu—a number not seen in a decade. But even if it doubled, it would still be below the cost of production. And if it tripled, it might still be below the cost of production for most producers. That’s how mispriced the commodity has become.

Misallocation of capital, and the resulting overproduction, is only part of the problem. The other part of the problem is horizontal fracking itself—a drilling method that extracts gas from shale formations. With nasty economics. It’s an expensive method. And once drilled, the well suffers from steep decline rates; after a year or a year-and-a-half, only 10% of the original production might still come to the surface.

The breakeven price for natural gas under these conditions—and it differs from well to well—is still partially theoretical since horizontally fracked wells have not yet gone through their entire lifecycle. But it’s unlikely to be below $5.00 per million Btu. At the current price of $2.53 per million Btu, the industry is still near its point of maximum pain.

There are consequences. Power generators, having switched massively from coal to natural gas, are driving up demand. And production has finally seen a bend, a small one, in the curve that had set new highs month after month. Now, it’s declining. There is a lag between dropping rig count and production. The rig count estimates how many new wells are being drilled. Even if it dropped to zero next week, production would not immediately be impacted because the current wells would continue to produce. Production would then taper off as a function of decline rates per well—and in fracked wells, that lag is expressed in months, not years.

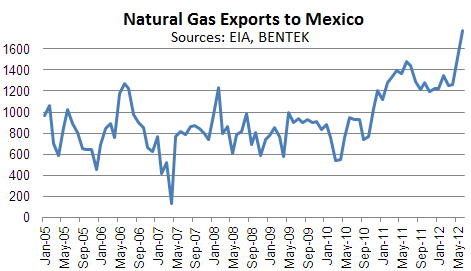

While the US doesn’t yet have LNG terminals to liquefy and export natural gas—in the global markets, LNG fetches mouthwatering prices between $10 and $15 per million Btu—it does have a pipeline to Mexico. According to BENTEK Energy (via the EIA), pipeline exports to Mexico hit 1,867 million cubic feet per day, a record in the seven plus years that BENTEK has been tracking it (by comparison, Chesapeake Energy produces about 2,575 MMcf/day).

Rising demand and exports are slamming into declining production. What was a record amount of natural gas in storage is coming down rapidly. Fears that storage would reach capacity towards the end of the injection period in the fall, and that natural gas would have to be flared, thus reducing its price to zero, seem ridiculous now. But prices, if they stay in the current ballpark, will continue to demolish producers, drive them away from dry natural gas, and cause financial bloodshed.

Until shortages appear on the horizon. But then, production can’t be ramped up quickly, regardless of what the price might be. Expect a spike and more mayhem, but this time in the other direction.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()