“In extreme overvaluation” – that’s how bond guru Marty Fridson characterizes the current junk-bond market. Junk bonds are supposed to offer high yields to entice investors to take on the risks. They’re still – somewhat quaintly – called “high yield” in polite society. But it has become a misnomer in this era when investors are scrambling to buy just about anything to get even a teeny-weeny bit of yield, regardless of the risks.

And now the risks are becoming apparent.

It’s been tough out there. In a daily drumbeat of bad news from the energy sector, Sabine Oil & Gas said it would skip a $15.3 million interest payment. It’s looking for strategic alternatives. It needs to restructure its balance sheet. Stockholders have already been wiped out. It now has a 30-day grace period before a default would be triggered. Its debt took a hit. According to S&P Capital IQ/LCD, its 9.75% notes due 2017 traded at 15 cents on the dollar.

But even as old money is getting wiped out, yield-starved investors keep pouring new money into the sector.

The same day, Halcon Resources, a fracking stalwart that has been drilling cash into the ground at dizzying rates, sold $700 million of second-lien junk bonds. So they didn’t come cheap, with a yield of 8.625%, according to LCD. Its shares are already a penny stock. The company said it would use the moolah to pay off part of its credit line; the bank is cutting the borrowing base from $1.05 billion to $900 million. And the old money? Halcon’s $1.35 billion of 8.875% notes dropped to 78.6 cents on the dollar. Back in June, they still traded at 109.

There has been a wave of teetering oil & gas companies that have been able to raise new money via second-lien debt to stay liquid a little longer. Energy XXI peddled $1.45 billion of second-lien notes in March at a yield of 12%. It would use the money to pay down its credit line that is getting cut in April. The old money got whacked: since the offering, XXI’s $650 million of 6.875% unsecured notes have plunged from 53 cents on the dollar to less than 36 cents on the dollar.

Goodrich Petroleum, sold $100 million of second-lien notes to pay down its credit line that would be cut in April. A slew of other energy companies have sold almost $10 billion of second-lien bonds so far this year, Bloomberg reported. A record pace for this type of security.

So the appetite for junk goes on.

“The extreme overvaluation of the high-yield market, initially observed in February, persisted in March,” Martin Fridson, Chief Investment Officer of Lehmann Livian Fridson Advisors, wrote in his column on S&P Capital IQ/LCD. Based on the firm’s econometric modeling methodology, junk bonds have been overvalued, though not at this extreme level, since mid-2012:

We believe this unusually long, unbroken stretch of overvaluation ultimately derives from a monetary policy that has the avowed purpose of driving investors into risky investments.

Money management organizations may employ historical-median arguments to persuade individuals and institutions to continue pouring money into the asset class, but HY portfolio managers acknowledge that it is difficult to find decent values these days. They feel somewhat safe in paying rich prices, however, based on the assumption that the Fed will continue to hold a safety net under the market. That strategy will succeed until it fails.

But underwriters have been licking their chops. Investors chasing yield to the Fed’s whistle are blind to risks. They buy anything with a little extra yield without reading the small print. They do what the Fed tells them to: take on more and more risks. And so they no longer demand the normal protections when they buy junk bonds.

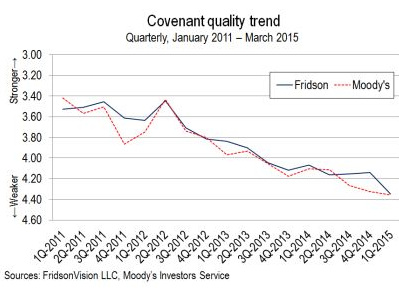

Hence, issuance of these “covenant lite” junk bonds has soared over the past few years as covenant quality has deteriorated. This chart by Fridson shows two measures: his (blue line) and Moody’s (red line). The scale ranges from 1 (strongest) to 5 (weakest). A multi-year trend that will be very costly for investors:

The deterioration of covenant quality in the first quarter is “not surprising,” Fridson writes, based on the inflow of new money into junk-bond mutual funds. As investors crowded in, issuers “took full advantage by obtaining bigger loopholes than ever before.”

There is a pernicious – for investors – long-term trend in play. Corporate debt issuers, thanks to the Fed’s machinations, have gained “the upper hand.” As Fridson put it:

Investment banks, whose ostensible role is simply to help borrowers and lenders meet at the market-clearing yield, would like to portray themselves as the equivalent of football referees, who merely mark the ball where it was downed and start the next play. This would be an apt metaphor if, as in football, an objective third party (the league) chose and paid the referee.

In reality, the issuer selects and compensates the lead underwriter. For most new issues, pricing is fairly predictable and the investment banks cannot compete on the basis of purportedly superior execution skills. Under these conditions, underwriters compete by seeing who can devise the trickiest ways of undermining the intent of the standard covenants.

This is particularly so with speculative-grade yields near their all-time low. Satisfied with their cost of debt, issuers are keen to exploit their advantage through ever more favorable borrowing terms.

OK, got it. Investor protections in the junk-bond market are going to heck. So why is this important? See Halcon’s latest bond sale, the second-lien notes.

Existing unsecured bondholders with weak protections got whacked when they couldn’t stop the company from issuing debt with second-lien claims on assets. The old money simply got shoved aside. They should have read the small print of the covenant. They’ll get even less during a debt restructuring or bankruptcy. And the value of these bonds dropped.

These investors have become sitting ducks.

That’s why weak covenants are treacherous for investors. But hey, this is the greatest credit bubble in history. We should celebrate it while we still can, not quibble with it. And besides, the real owners of these bonds will never know. They’re hard-working Americans with conservative-sounding bond mutual funds in their nest eggs where these kinds of losses can fester in the dark.

But not every central banker thinks that this will end in bliss.

Agustín Carstens, governor of the Bank of Mexico and chairman of the IMF’s International Monetary and Financial Committee, is not an opponent of QE and interest-rate repression. Or at least, he toes the line. But he unleashed some stark warnings about how all this might turn out. Read… Central Bank Governor Veers Off Script, Sees “Illusion of Liquidity” & “Asset Bubbles,” Dreads Crash

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

…”But even as old money is getting wiped out, yield-starved investors keep pouring new money into the sector.”…

That is funny, new money from new sheep looking to get sheared. Are these people that stupid to flush their money away for a possible chance to make that crappy yield? Go to a casino, or better yet preserve your principal for a rainy day in your mattress. Peak stupidity.

I can’t imagine that many buyers are using their own money for these purchases.

Like the equity market where the price of shares have no relationship to the underlying value of the company, these junk bonds are also not tied to the underlying value of the assets of the issuer. The value of these junk bonds is solely based on the power of the holders and their ability to influence the govt. Buyers with power get bailed out, so invest in junk bonds held by the big players. They will never get a haircut. You just need to ride the right wave.