Differences in the Cost of Social Contributions and Cost of Labor across the EU

The ominous term, “competitiveness” has been bandied about as the real issue, the one that causes European countries, in particular some of those stuck in the Eurozone, to sink ever deeper into their fiasco. To fix that issue, “structural reforms,” or austerity, have been invoked regardless of how much blood might stain the streets. And a core element of these structural reforms is bringing down the cost of labor.

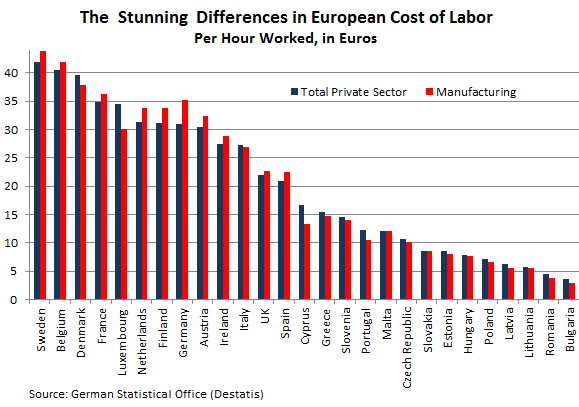

In Europe’s private-sector, the cost of labor—gross earnings plus employer-paid social contributions, pensions, disability, etc.—is marked by stunning differences.

At the bottom of the spectrum is Bulgaria: the average private sector employee costs a company €3.70 per hour worked; in manufacturing even less, €2.90. Romania is right there at €4.50 and €3.80 respectively.

Near the top of the spectrum is Belgium at €40.40 and €41.90 per hour worked. But no one beats the Swedes: €41.90 and €43.80. Per hour worked, the average Swedish employee costs a manufacturer over 15 times more than an employee in Bulgaria.

So, relocate all manufacturing plants from Sweden to Bulgaria? Or Romania? Even Greece would be a great place. The cost of labor there is only €14.70 per hour worked, about a third of what it costs up north. It’s the only country in the EU where the average cost of labor actually fell in 2012—and by 6.8%!

In Spain, which struggles with a similar unemployment problem, cost of labor rose by 1.1% to €20.90, in Italy by 1.7% to €21.90, in Germany by 2.8% to €31, in France by 1.9% to €34.90. The biggest gainers in percentage terms were at the bottom: in Bulgaria, cost of labor rose 6.4%, a whopping €0.24 per hour! In euro terms, the biggest gainers were at the top: cost of labor in Sweden rose 3.5%, or about €1.50 per hour! The cost of labor at the top is running away.

Based on data from the German statistical agency Destatis, this is what it looked like in 2012:

But if enough Swedish companies—and not just manufacturers but all kinds of companies—packed up their machines and robots and cubicles and headed south, unemployment would rise in Sweden. Once unemployment pushes deeply into the double digits, executives will defend their delocalization decisions by lamenting the cost of labor, and soon the government will be talking feverishly about “structural reforms,” without meaning it, and that’s where France is right now. But eventually the situation might deteriorate and pressure wages and associated costs. This has happened in Greece. And they’re all competing with the US, China, Mexico, Bangladesh…. Because competitiveness is not just a beggar-thy-neighbor system.

Alas, the rejuvenated “sick man of Europe,” Germany, isn’t surviving just by cutting its cost of labor. At €31 per hour, it was 32% higher than the EU average, though 11% lower than in France. In manufacturing, it was even more striking: Germany’s cost of labor of €35.20 per hour was 47% higher than the EU average, but still 3% lower than in France. Productivity, infrastructure, transportation costs, corruption, training and education, etc. all figure prominently into this equation. Cost of labor is not the only factor.

Yet German workers have been hit hard: between 2001 and 2010, the cost of labor grew 16%, less than the rate of inflation, while in France, for example, it grew 35%, and in southern countries it jumped far more. In 2011 and 2012, Germany’s cost of labor began to rise with renewed vigor, up 5.9%, but so did France’s at 5.4%.

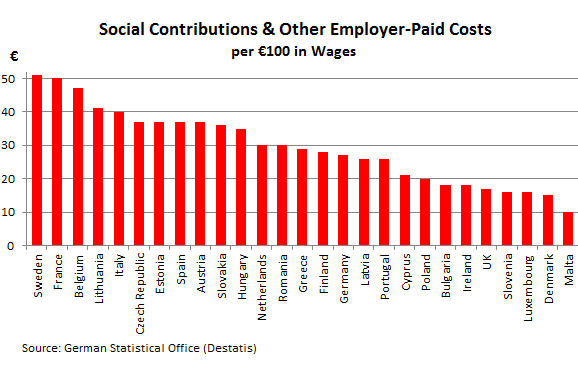

Much of this money was absorbed by the costs of social contributions, pensions, etc. And they can be breathtaking. The graph below shows these additional costs to the employer per €100 in gross wages paid.

So an average worker in Sweden who earns €100 for a certain number of hours in gross wages costs his employer an additional €51, for a total cost of €151. A Maltese worker, who’d work about three times as long for the same pay, would cost the employer only an additional €10, so €110. And a Bulgarian worker who’d work about 15 times as long for the same pay would cost an additional €18, so €118. This is a conundrum looking for a solution.

Over time, “competitiveness” hollows out the middle and lower classes in some “rich” countries—this has been happening in the US and Germany for years—balloon the middle class in other countries, and make the top in all countries immensely rich. For many people, it’s nothing to look forward to.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()