Natural gas traded at $3.22 per million Btu (MMBtu) at the Henry Hub on Monday, a seven-month high, and a jump of 69% from its April low. Breathtaking when you think that a few months ago, the doom-and-gloomers, who’d been right for a very long time, were predicting chillingly that the price would hit zero by the fall, when storage would be full and excess production would have to be flared. But the pains for the industry are far from over.

Natural gas spot prices can spike locally due to transportation constrains and demand conditions. Earlier this year, while Japan paid $17/MMBtu, New York $12/MMBtu, and Boston $9/MMBtu, prices at the Henry Hub, which is in southern Louisiana, marched towards their decade low and dropped below $2/MMBtu.

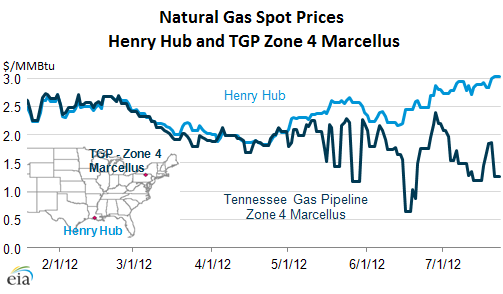

Conversely, there are regions in the US where natural gas prices lag behind those at the Henry Hub. A salient example is the daily spot price at the Tennessee Gas Pipeline (TGP) Zone 4 Marcellus, a hub that serves part of the vast Marcellus formation that extends across much of Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York.

Drilling by horizontal fracking has been phenomenally successful in this shale formation. In Pennsylvania, production of dry natural gas in June has doubled over last year, reaching 5.7 billion cubic feet per day—9% of overall US production. But it outstripped the take-away pipeline capacity, despite new pipelines that entered service in 2011 and added 1.5 Bcf/d in capacity. As a consequence, according to Bentek Energy, over 1,000 natural gas wells in northern Pennsylvania are not yet producing natural gas because of pipeline constraints.

With production outrunning pipeline capacity and creating a local glut, spot prices have separated from those at the Henry Hub. At the TGP Zone 4 Marcellus, starting in May, prices fluctuated widely and dipped below $1/MMBtu even has prices at the Henry Hub had started their track towards $3 MMBtu.

Producers in that region are hurting even more than elsewhere. The 1,000 wells that have been drilled but aren’t producing and cash-flowing yet are a drag on the companies that own them. And wells that are producing have had to sell their unhedged production at a discount to already depressed prices that remain below the cost of production in most of the nation. So the natural gas massacre hits northern Pennsylvania with even greater violence.

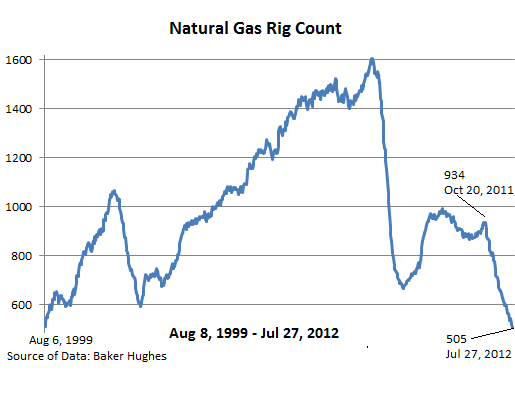

Rig count is a good indicator of the health of the drilling industry, and also of the direction of future production—though there is a considerable lag between the number of rigs drilling for gas and actual production of gas. And the rig-count is beginning to be worrisome. At 505 rigs as of July 27, the count is down 46% from October last year, and hit the lowest level since July 1999.

Somewhere between 700 and 900 rigs might be required to maintain current production levels, given the sharp decline rates of horizontally fracked wells (up to 90% over the first 12 to 18 months). These wells will then have to be refracked, or new wells will have to be drilled to make up for the declines—at an additional cost. An eternal rat race. But the hard-hit industry is stepping away from drilling for dry natural gas; drilling at today’s prices is still a losing proposition. Those that can have switched to drilling for oil and natural-gas liquids (priced similar to oil), which are profitable. Of the natural gas rigs in operation—fewer and fewer every week—an increasing number are focused on plays that contain more liquids and less dry natural gas. It’s how producers hope to survive.

Turmoil and financial stresses may further reduce drilling activities—though it seems unthinkable that the rig count could fall even further! Record demand is eating up the remnants of the glut. Supply appears to be leveling off and will eventually follow the rig count down. If that happens during heating season, when seasonal demand skyrockets, it will be an unholy alliance. We have seen violent spikes before. And we will see them again. It’s the nature of the business.

In the great natural gas shakeout, less efficient or poorly capitalized producers may get wiped out. It’s capitalism’s creative destruction. But the price of natural gas has been below the cost of production for so long that the damage is now huge.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()