Bonus: His doomsday scenario if Congress forces the Fed to stop paying interest to banks on their reserve balances.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Powell in his speech today discussed the Fed’s balance sheet, including:

- When QT might end: “In coming months,” he said in the speech; “We’re not so far away now, but there’s a ways to go,” he said in the Q&A.

- How the balance sheet’s composition might change: Shifting to short-term T-bills and getting rid of the MBS entirely, including by selling them.

- How doomsday would unfold if the Fed were forced to stop paying the banks interest on their reserve balances.

The Fed has been operating officially under the “ample reserves regime” since early 2020. Reserves represent liquidity that banks keep in their reserve accounts at the Fed to pay each other on a daily basis as part of the payments system; to have liquidity on hand to deal with large swings of liquidity as they occur; to earn risk-free interest; and boost their regulatory capital.

“Reserves” are a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet (amounts it owes the banks). The Fed pays the banks interest on their reserve balances, at a rate that is one of the five policy rates the Fed set at the FOMC meetings. Reserves are key.

When QT might end:

“Our long-stated plan is to stop balance sheet runoff when reserves are somewhat above the level we judge consistent with ample reserve conditions,” he said in his prepared remarks.

“We may approach that point in coming months,” he said. But then in the Q&A, he put the “coming months” into perspective:

“We’re not so far away now, but there’s a ways to go.”

Even after QT has ended, “reserve balances will continue to gradually decline as other Federal Reserve liabilities grow over time,” he said.

When QT ends, total assets remain level, and so total liabilities remain level, but as the other liabilities increase based on external demand, reserves will shrink further.

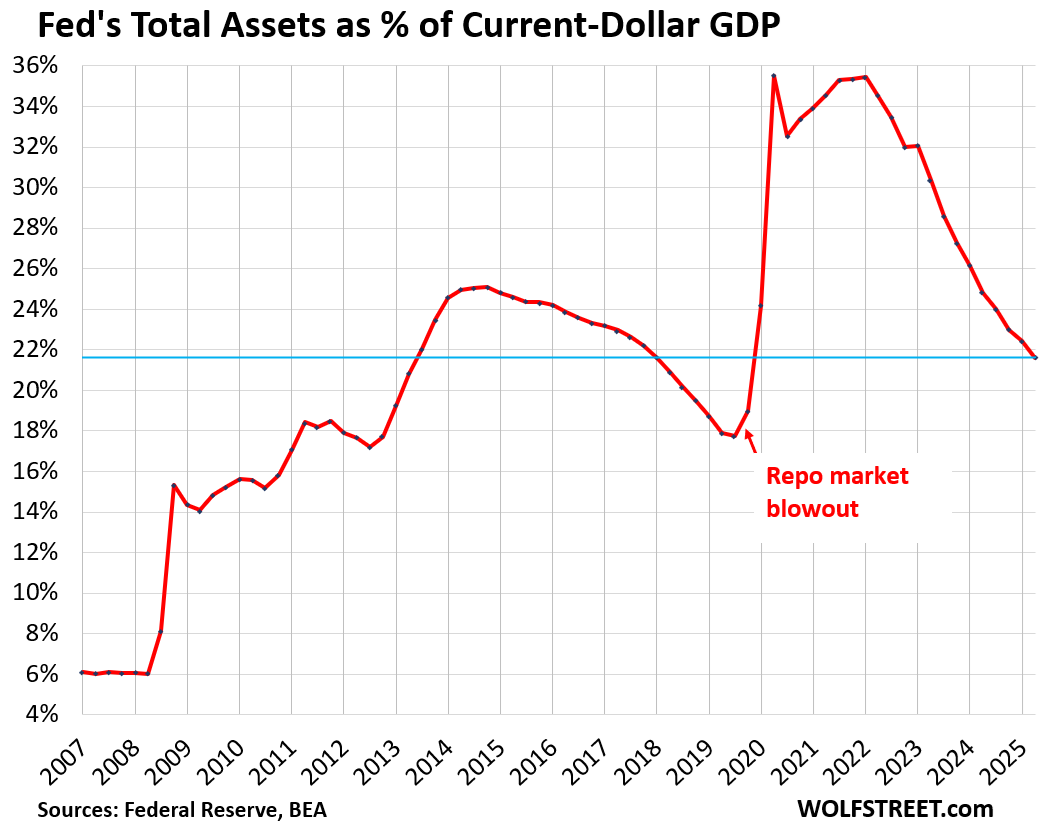

As assets remain level, while the economy grows, total assets as percent of GDP would decline further, which is a soft form of QT. The ratio has already declined from nearly 36% in 2022 to 21.6% currently. The ratio would continue to decline after QT ends, but more slowly.

This also occurred from the end of 2014 through 2017 when total assets remained flat while the economy grew, and the ratio therefore declined. QT-1 was phased in at the very end of 2017 and ran through mid-2019, which accelerated the decline of the ratio.

Even before 2009, before QE, the Fed’s assets grew roughly with the economy, which is the normal condition (my discussion of the Fed’s assets).

The three other “Federal Reserve liabilities”:

- Currency in circulation (paper dollars, currently $2.4 trillion), which are demand-based, about half held overseas.

- The government’s checking account (Treasury General Account or TGA) currently about $800 billion.

- Reverse repurchase agreements, by which counterparties can deposit cash at the Fed. They come in two flavors:

- Overnight reverse repos (ON RRPs) with US counterparties, such as money market funds. After three years of QT, they’re down to near-zero.

- Reverse repos with “Foreign official and international accounts,” $350 billion, with which foreign central banks deposit their USD cash at the Fed.

“A little bit of tightening in money market conditions.”

“Some signs have begun to emerge that liquidity conditions are gradually tightening, including a general firming of repo rates along with more noticeable but temporary pressures on selected dates,” he said.

In the Q&A, he referred to it as a “little bit of tightening in money market conditions.”

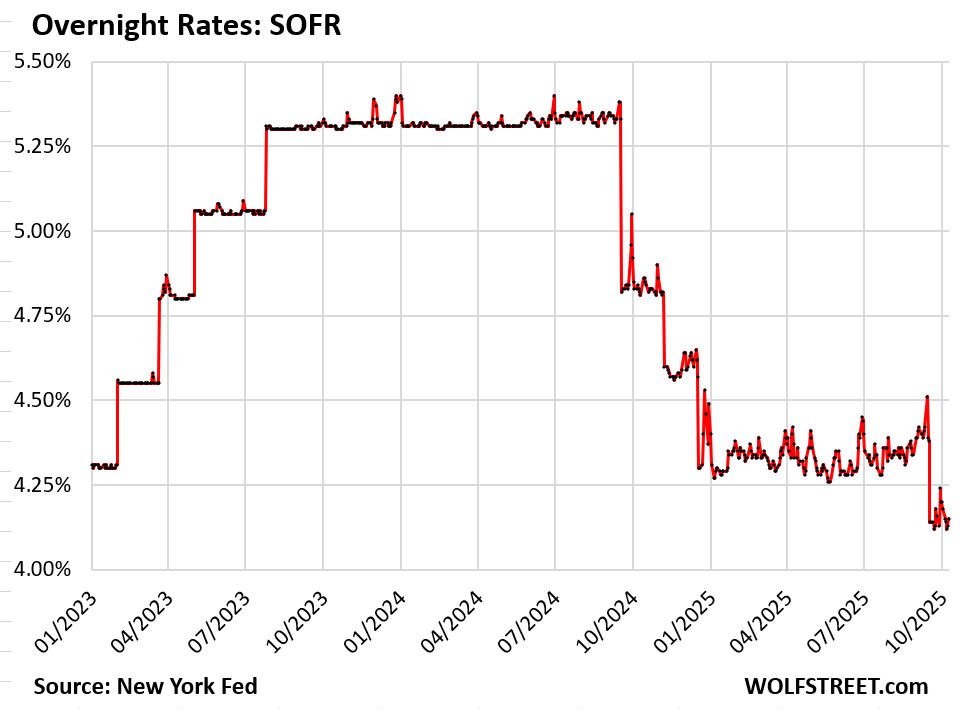

For example, some rate volatility has crept into the $3-trillion-a-day portion of the repo market that is tracked by the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), especially around month-end, quarter-end, and tax-day periods, when large amounts of liquidity get moved around.

In the days leading up to September 15, as companies paid corporate estimated taxes, SOFR rose by about 12 basis points over a three-day period to 4.51% (and higher intraday) on September 15, before settling back down to 4.38% on September 17.

When the rate cut became effective on September 18, SOFR dropped by 24 basis points to 4.14%, but then rose again to 4.24% by September 30 amid month-end liquidity flows. On Friday, October 10, it was back at 4.15%.

Already a year ago, Dallas Fed president Lorie Logan said: “Such temporary rate pressures can be price signals that help market participants redistribute liquidity to the places where it’s needed most. And from a policy perspective, I think it’s important to tolerate normal, modest, temporary pressures of this type so we can get to an efficient balance sheet size.”

And if these liquidity pressures start getting out of hand, and repo rates spike, banks can borrow at the Fed’s new and improved Standing Repo Facility (SRF) and at the improved Discount Window at the Fed’s policy rates and lend to the repo market risk-free at the spiked repo rates and profit from the spread.

This supply of cash to the repo market would cause repo rates to settle back down toward the Fed’s policy rates, while earning banks a bundle.

Back in 2019, when the repo rates blew out, the Fed didn’t have the SRF, and the Fed ended up directly entering the repo market. Powell referred to that in his discussion.

Changing the composition of the assets:

He re-iterated the coming shift to short-term Treasury bills for part of the portfolio, which has been discussed by other Fed governors and presidents before, and re-iterated that the Fed would be getting rid of its MBS entirely, and that it might sell them outright.

“Relative to the outstanding universe of Treasury securities, our portfolio is currently overweight longer-term securities and underweight shorter-term securities. The longer-run composition will be a topic of Committee discussion,” he said, and so it will crop up in the minutes over the next few months.

“Transition to our desired composition will occur gradually and predictably, giving market participants time to adjust and minimizing the risk of market disruption,” he said.

“Consistent with our longstanding guidance, we aim for a portfolio consisting primarily of Treasury securities over the longer run,” he said. And he added in his footnote 21:

“As noted in the minutes of the May 2022 FOMC meeting, the Committee could, at some point, consider sales of agency MBS to accelerate progress toward a longer-run SOMA portfolio composed primarily of Treasury securities.”

His doomsday scenario if the Fed cannot pay interest on reserves.

There has been some talk to prohibit the Fed from paying interest to the banks on their reserve balances. Powell is not a fan of that. So he outlined this doomsday scenario that would unfold if the Fed were forced to stop paying interest on their reserve balances. So for your amusement, in Powell’s own words:

“If our ability to pay interest on reserves and other liabilities were eliminated, the Fed would lose control over rates. The stance of monetary policy would no longer be appropriately calibrated to economic conditions and would push the economy away from our employment and price stability goals.

“To restore rate control, large sales of securities over a short period of time would be needed to shrink our balance sheet and the quantity of reserves in the system.

“The volume and speed of these sales could strain Treasury market functioning and compromise financial stability. Market participants would need to absorb the sales of Treasury securities and agency MBS, which would put upward pressure on the entire yield curve, raising borrowing costs for the Treasury and the private sector. Even after that volatile and disruptive process, the banking system would be less resilient and more vulnerable to liquidity shocks,” he said.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

I’ve generally been a fan of Powell. But his “doomsday claim” were the Fed to stop paying interest on bank reserves is total BS.

Prior to Oct 2008 (and the GFC) they did not pay interest on reserves.

One more “crisis response” that turns permanent.

Depressing…

For better or worse, banking has changed since before 2008. If interest was not paid on reserves then banks would keep very minimal reserves at the FED. Banking volatility would be very high.

Steve,

When I read that doomsday scenario, I had several thoughts, on top of which were:

1. Ok, cool it JPow, that’s exaggerated fearmongering.

2. It would probably work just fine, and would cure a lot of distortions, if:

A.) they phase in the no-interest on reserves over a period of time so banks could adjust to it,

B.) they reinstitute big reserve requirements (“required reserves”) to force banks to keep enough reserves at the Fed, such as 15%, which would keep reserves at every bank fairly high (they just wouldn’t get paid interest on it).

Just keep the SRF handy to douse any brush fires before they get out of hand.

JimL,

That’s a non-issue if reserve requirements are re-imposed, as they used to be. Until 2020, reserve requirements were 10%. But maybe they should be lifted to 15%.

Exactly. Talk about ending interest on reserves without reinstitution reserve requirements is just dumb and irrelevant. The Fed could even keep paying interest on excess reserves but do it at a floor level policy rate where banks would normally prefer to lend to other banks or NBFIs within a policy band.

These were my thoughts while reading the story.

It seems to me that paying interest on reserves is counterproductive, and excess reserves by the largest banks could be penalized.

I’m with Steve

Interest paid on Reserves is functionally a taxpayer-funded, back-door bank subsidy. Interest Not Paid on reserves would legally be remitted to U.S. Treasury.

The Doomsday scenario is bogus. Banks not being paid on Reserves would buy T-Bills (similar yield, nearly as liquid, nearly as privileged). The Fed would be selling their excess T-Bills into the same market. No one would be harmed. And the Fed would be better immunized against claims that it’s monetizing the debt or robbing taxpayers to pay bankers.

The Fed managed short term interest rates for nearly a century without interest on reserves. Surely they could remember how to do that again.

Maybe economist John Hussman is full of it, but he claims in his September, 2025 market comment that the Fed’s balance sheet would have to go below 10% of GDP before market forces alone (ie, not paying interest on reserves) could keep interest rates above zero.

that makes zero sense.

His statement is derived from the “Liquidity Preference Curve” that he’s discussed for over a decade, and which he says it’s one of the most reliable in economics. I suspect he’s got a mistake somewhere (not taking into account the TGA account, US currency held in foreign countries, etc.), since I remember you saying the lowest the Fed balance sheet can go is about $5.7 (?) trillion.

Hussman’s quantitative arguments usually make a lot of sense.

I’m not sure how to include here his chart, just trying:

The Fed has another floor rate (in addition to IOR): the ON RRP rate. If there is no IOR, and if market rates drop below the ON RRP rate, counter parties (banks, money market funds, etc.), will put their available cash into ON RRPs. And rates won’t drop much below that because all available cash will sit in the ON RRPs waiting for higher bidders. If the Fed maintains the ON RRP rate, that’s about where rates will bottom out.

The rates for the SRF, and the Discount Window are ceiling rates.

For rates to fall below the Fed’s policy rates, the Fed would have to scuttle its ON RRP rate.

But what Powell was talking about in the Doomsday Scenario, which I cited in the article, was that the Fed would have to SELL lots of securities at a very fast clip to slow down the overheating economy and inflation by bringing reserves down to much lower levels, and fast, which would push up long-term rates. There is only $2 trillion in reserves that can be drained at all, because banks need some cash in their checking accounts at the Fed (reserve accounts) to pay each other. So if the Fed sold $2 trillion in assets — the maximum possible – total remaining assets would still be 15% or so of GDP.

And as long-term rates surge due to those security sales, short-term rates would remain fairly high because money would flee from short-term securities into the high yields of long-term securities to mop up the $2 trillion the Fed would be selling.

I am out of touch enough to not know that pre 2008 interest was not paid. While post 2008 it was.

What is normal in the rest of the world?

EXACTLY. The Fed is an abomination that has facilitated bad behavior by CONgress and the greatest wealth transfer (from labor to capital) the world has ever seen.

Interesting times.

If actively selling MBS will further bring home price back down to reality or fundamentals, then a big giant thumbs up to the FED for mentioning it and reserve another one for them when they actually get around to doing it…

Really shouldn’t have bought the insane amount during covid time, but whatever, it’s done, at least undo some of the damage so people don’t continue to normalize million dollar crap shack in SoCal as the baseline entry price to homeownership…

I’m not sure this would happen. If the Fed sold their existing MBS they would have to compete with new mortgage securities and accept a price that yields around 6-7%. On a fixed 3% bond that’s a big principal loss. Sixty cents on the dollar maybe. The Fed taking losses on old MBS won’t affect current mortgage rates or current house prices.

Now if the Fed is barred from ever buying MBS again then the price distortions of 2010-2022 could be avoided and house prices could actually reflect market conditions including actual interest rates.

Is there an estimate on the increase in interest rates as the result of the current QT?

25 basis point is likely. yet all are putting pressure on Fed go with 50 basis point. Market is behaving as if 50 basis point is a sure thing. Sometimes this tactic works because if not market shock will be “too much to manage” as market (really just irrational minds collectively behind screens) doesn’t like surprise – if this makes sense intuitively.

Greater than 0% and less than 100%. There are way too many variables to estimate with any degree of accuracy within 1% what interest rates will be in a 1-year time frame. There are global factors at play, not just domestic. As Wolf has written about in a recent piece, central banks worldwide are performing QT, so global capital supply is shrinking (at least in the countries/regions Wolf has covered). Folks globally have the ability to buy MBS and U.S. treasuries, which impact mortgage rates. One thing is certain: the future is uncertain.

Jerome Powell’s speech was getting rid of mortgage back securities (MBS) entirely (per Mr. Wolf’s article) and “we’re not so far away now …” (Mr. Wolf quote).

However. going to the Federal Reserve (FRED) data:

“Securities Held Outright: Mortgage-Backed Securities: Wednesday Level (WSHOMCB);” shows a peak of about $2.7 trillion in June 2022 and about $2.1 trillion Oct 8, 2025 (end of graph). The downward slope of the decrease looks like a straight line at the graph’s resolution.

Analysis: That is a $0.6 trillion ($600 billion) reduction in a little over 3 years; there is more than 3 times (3X) that left to go on a straight line graph, that is over nine years, let’s call it 10.

Conclusion: The only way Powell’s comments could both be right is if they refer to independent events: 1) he is going to quit QT soon regardless of what the MBS is on the balance sheet; and 2) someday longer than 10 years (if he quits QT) the Federal Reserve will run out of MBS; essentially stating the obvious that the MBS will run out when the mortgages are all payed off: including running them to the end of their term – he doesn’t need any QT for that, so it’s a “half true (half truth).”

No. After QT ends, they will continue to get rid of MBS and replace them with T-bills.

They did that last time during QT-1. QT-1 ended in mid-2019, but MBS kept running off full blast at the cap every month through February 2020 until Covid. As they ran off, they were replaced by T-bills.

Ok Wolf, I’m the dumbo in the class with the big ears, and maybe not the sharpest tool in the shed, but I can put 2 and 2 together – If Congress forces the Fed to stop paying interest to banks on their reserve balances, I’m pretty sure ‘the banks’ are not gonna pay us nuthin’ on our money in the bank. Correct? Do I get the ‘Best Student’ of the month award? Dumbo’s mama gonna be real proud!

p.s.: this crap is getting scary. Doomsday?

The interest that banks pay depositors for their cash is a function of how badly banks need the cash from depositors and how much banks are competing to get that cash by offering higher rates. With liquidity less abundant, banks compete with each other, and with money-market funds, T-bills, etc. for cash. So what banks pay is a function of competitive pressures, the need for cash, and short-term money-market rates. It’s not a function of interest on reserves (but in the current set-up, the interest rate on reserves help bracket repo rates at the upper end).

If your bank screws you on rates, you have to shop around, look at money market funds and T-bills, etc. for your interest-earning cash.

No excuse for not getting rid of the MBS. They should have gotten rid of them years ago.

I get an undertone/hint of possible crisis –

1) “…. if Congress forces the Fed to stop paying interest to banks on their reserve balances.”

2) “If our ability to pay interest on reserves and other liabilities were eliminated, the Fed would lose control over rates.”

3) ““To restore rate control, large sales of securities over a short period of time would be needed to shrink our balance sheet and the quantity of reserves in the system. ”

I may get the next flight out to the Caribbean. Oh – after making a withdrawal at my local bank. 😜

If, as Powell says, “ample” reserves are essential to keep the banking system functioning with adequate liquidity, the cost should be borne by the banking system itself (not the taxpayer).

Not paying interest on reserves would save taxpayers around $110 billion (plus or minus) per year. Now Powell wants this lucrative freebie for banks to end, so it will probably remain $100B/yr (plus or minus) if QT ends in a matter of months. This means another $1T wealth transfer to bank stockholders over ten years. This at a time when regular folks are seeing cuts to health care and other safety nets.

Internalizing this cost to the banking system would enable Powell to continue to control short term rates. One way would be to impose an infinitesimal Fed surcharge on the interest rate itself. Given the magnitude of all interest charges in the economy (including charges by the non-bank FIRE sector, which also contributes risk to the system and benefits from this liquidity cushion), this surcharge would probably be in the 3rd or 4th decimal place–maybe tenths or hundredths of a basis point.

Sadly, doing this would contradict a cardinal rule of for-profit capitalism: internalize profits, externalize (socialize) costs (e.g. onto the taxpayer). And for this, bankers get big bonuses too!

The Fed pumped huge excess reserves into the banking system and then asked Congress for the authority to pay interest on those reserves. This is a gift to the banks, ultimately paid for by the taxpayers, because the interest paid on reserves reduces (or eliminates) the profits that the Fed pays to the Treasury. What was wrong with the regime of scarce reserves? I suspect that when the next financial crisis strikes, “ample reserves” will do nothing to mitigate it.

Bankrupt-u-Bernanke created a crisis of an order in magnitude of the Great Depression that he couldn’t control. It was the first time since the GD that there was commercial bank disintermediation.

Contraction by any single bank in the system placed pressure on other banks, and since their excess-reserve positions were inadequate, and the banks were unable or unwilling to replenish their excess reserves through the agency of the FED a multiple process of credit contraction ensued.

Bernanke originally thought the GFC represented a capital crunch (hence the Treasury’s TARP and the Capital Purchase Program, etc.), not a credit crunch.

See Scott Fullwiler:

“Paying Interest on Reserve: It’s More Significant Than You Think”

Your link didn’t lead to the article. So I took it out. The article can easily be googled with the headline. The article is from 2004, before the Fed paid interest on reserves.

Housing market chaos as one in seven buyers across the US pull out of deals at the last minute – in chilling echo of 2008 crash

The housing market across the US is seeing a meltdown.

Complete bullshit, this is a long overdue correction. Prices are still way too high relative to wages.

I think Powell wants the IOR lever because it is easier to operate than increasing or decreasing the money supply to manipulate interest rates. Maybe he is also concerned that congress will never get a grip on spending. Wouldn’t a lower IOR encourage banks to move money into the real economy? This may result in more growth but also more inflation right?

Yes, if the Fed didn’t pay interest on reserves, Banks would try to replace a non-interest bearing assets (reserves) with assets that paid interest (loans). But if reserves are scarce, Banks will borrow reserves rather than passively collect interest on them. The system of scarce reserves worked well for many years. It was abandoned by the Fed after the GFC because the QE created huge excess reserves. In the language of central bankers, these excess reserves had to be “sterilized.”

That language always made me laugh. Yeah, give me access to the printing press, I’ll “sterilize” all the reserves you want!

George Carlin was right all along.

The FED always thought reserves were a tax [sic]. Not so, they are “Manna from Heaven”, costless and showered on the system.

“This may result in more growth but also more inflation right?”

I think that is exactly what Powell was warning of, that $2 trillion would suddenly be unleashed into the economy via loans as banks were trying to put this cash to use, thereby stimulating demand, overheating demand, triggering inflation, and that the Fed would have sell securities in large amounts to counteract that, which would push up long-term interest rates and cause all kinds of problems, according to him.

Wolf,

The flipside of that is of course, that someone who behaved badly in 2008/2009 has gotten exceptionally wealthy because they were bailed out.

Making productive loans to actually build/innovate right here at home in America, may be exactly what we need right now.

Wolf, so if the Fed slowly decreased the interest rate on reserves—say 4 to 5 basis points every month—would this be a reasonable taper to have banks slowly loan out money and not shock the economy? As other commenters have noted, paying interest to banks on the reserves that the Fed put into their pockets feels icky. That estimated $100 billion per year of interest paid to banks on reserves at the taxpayer’s expense should be brought back to $0 like before 2008.

Yes, maybe something like a slow taper of the IOR rate.

But the main thing is that the Fed would need to re-institute big reserve requirements (“required reserves”) to force banks to keep enough reserves at the Fed for liquidity reasons to keep the banks from collapsing at every minor run. Until 2020, required reserves were 10%, but maybe start with 15%, which would keep reserves at every bank fairly high (they just wouldn’t get paid interest on it), and would prevent too much sudden stimulus of the economy.

China’s PBOC adds or subtracts stimulus by changing the reserve requirement of Chinese banks. This is a classic method of managing money supply to stimulate or cool the economy.

Ok, so a taper (decrease) of the IOR rate to about 4 to 5 basis points per month, and the Fed instituting a rule that banks must increase reserves to 11% by 6/1/2026, 12% by 1/1/2026, etc. such that total reserves are increased on a 6-month interval. This maintains balance in the system and doesn’t apply too much pressure to banks to come up with the cash quickly to add to their reserves.

Once 15% is reached, the Fed can evaluate whether reserve requirements should increase further.

Another option would be the banks buying short dated treasuries if the IOR were to go away. Especially if the short term treasury rates were higher than the IOR. If the FOMC decreased the IOR systematically they could engineer a transition to short term treasuries or money markets paying a slightly higher yield. They would still have the SRF to handle any sudden disruptions. We may then actually have interest rates that would reflect real market conditions.

and, the REAL rate of inflation!

Correction should be IOER-interest in excess reserves.

Powell is worried about what market forces would do after 2-3 decades of harmful stimulus. He wants the economy on Xanax forever.

It also goes to show that a substantial portion of any increase in the balance sheet is almost definitely going to become structural unless 1) it’s withdrawn relatively quickly and 2) there’s a plan in place from the beginning to remove it, as with the Silicon Valley Bank program.

If it’s just “We’ll increase and see what happens,” the economy will adjust to that extra liquidity, and they won’t be able to fully withdraw it without any pain, which they’ve shown they’re not willing to tolerate.

He seems to have done a pretty good job so far cleaning up the last crisis. But he must sometimes wake up in the middle of the night with the nightmare of stagflation along with a housing and market crash.

So taxpayers stop gifting banks a bunch of free money + fed stops distorting the market with massive debt holdings.

Sounds like a win-win for everyone except bank shareholders.

Yes, and take the banks off the IOR free lunch program.

have you seen bank shares lately? I know my JPM is up almost 300% since 2022. I’ll happily pay the 15% capital gain now that I sold…

A truly “independent Fed” would continue QT and hold CONgress’ feet to the fire to act responsibly and balance the budget.

It’s that or precious metals, and other commodities, continue their parabolic rise. What people forget is that FOOD is indeed a commodity, or at the very least, food production requires commodity input…

Hedge accordingly.

I don’t claim to understand all the “operation under the hood” of our Fed/Treasury money system.

But I do understand the signficance of the $37 T debt (current) and $2T/year deficits.

I also understand fully how China has cleaned our clock in high tech manufacturing as well as cornering huge critical industries that no one else bothered to mess with. Also, I fully understand how much gold China has accumulated and what appears to be a fairly transparent plan to use gold to (at least) partially back Yuan settlement with other trading partners.

All this combined is going to have enormous impacts on the US dollar in the coming years. So the 100B tinkering with interest paid to banks is going to look like a really, really trivial issue in the grand scheme of things.

China has a huge complex and still relatively fast-growing economy. Trying to strangle that economy by tying the renminbi to gold could be catastrophic, and Chinese leadership is laughing off this nonsense.

But due to this huge trade surplus with the rest of the world, China gets a lot of foreign currency, topped off by the USD and EUR, that it has to do something with, such as purchasing commodities, components, and products from overseas, and buying USD-denominated securities, EUR-denominated securities, gold, etc. So part of its haul of foreign currency is used to buy gold. It does not buy gold with its own currency.

BTW, this is commonly confused, but the currency is the renminbi (RMB), not “yuan”; yuan is a basic unit of the RMB, as in “the widget costs 10 yuan.”

I believe Milton Friedman offered this position

He suggested that the Fed should pay on required reserves.

So, a good compromise and a return to “normalcy” would be to reinstate required reserves and pay interest ONLY on those required.

Curious that the Fed, which is assumed to control ONLY short term rates, has an “over balance” of long paper.

What are they doing at all in the long end? It seems to be a residue of their efforts to drive long rates to all time lows during COVID.

So much for the Fed only manipulating short rates.

I hope that one day, Mr. Wolf will write a column on Fractional Reserve Banking. While this practice is essential to our economy, does the practice create some amount of devaluation of American and other dollar holders’ purchasing power?

Simply asking why our dollars buy less each year, is it just programs like QE, or are other issues involved?

here is my one-sentence article: This whole nonsense about “Fractional Reserve Banking” is just silly to non-gold-bugs.

The National Financial Conditions Index disagrees with Powell’s assertion that “liquidity conditions are gradually tightening”. In fact, the NFCI continues to show loosening.

What’s the disconnect?

1. The NFCI measures “financial stress” — largely how hard it is to get credit — not liquidity. Two very different measures.

There can be lots of liquidity, but if it doesn’t go where it is needed, financial stress forms where liquidity is in short supply, so in that corner, yields rise, spreads widen, etc., which is what financial stress indices measure.

2. What Powell was talking about, and what the chart I posted shows is that liquidity in the repo market is beginning to normalize, from the very excessive levels before, so it is “gradually tightening” from those excessive levels.

Paying the banks interest on their liquidity reserves, their free reserves, must be higher than what the banks would receive based on their average net interest rate margins or the banks will buy higher, more profitable, short-term instruments.

The problem is that the FED shouldn’t be using interest rate manipulation to steer the economy in the first place.

Monetary policy objectives should be formulated in terms of desired rates-of-change in monetary flows [ M*Vt ] relative to rates-of-change in real-gDp [ Y ]. Rates-of-change in nominal-gDp [ P*Y ] can serve as a proxy figure for rates-of-change in all transactions [ P*T ]. Rates-of-change in real-gDp have to be used, of course, as a policy standard.

I’m curious about what happens if the Fed goes beyond considering “sales of agency MBS to accelerate progress toward a longer-run SOMA portfolio composed primarily of Treasury securities” and actually starts selling the stuff. My limited understanding of banks is that they maintain two pools of assets: Available For Sale (AFS) and Held To Maturity (HTM). The AFS stuff has to be marked-to-market.

I interpret the Fed’s actions up to now as treating the entire MBS pool as HTM. Are they going to have to identify an AFS pool and then mark all those MBS bonds to market at once? Seems like doing that in bulk periodically would show up as sudden drops in their balance sheet.

1. Losses don’t matter to the Fed, which creates and destroys money on a daily basis every time it pays for something or gets paid for something.

The unrealized losses are disclosed on the Fed’s quarterly financial statements. So we know what they are.

2. Currently about $15-20 billion in MBS come off every month via pass-through principal payments. The Fed has set a roll-off cap of $35 billion a month. So if the Fed sells $15-20 billion a month to get to the $35 billion cap, the monthly realized losses would be a portion of the $15-20 billion in sales, such as $6 billion a month in losses, which means nothing for the Fed. This isn’t even an issue.