Long-term yields matter to the economy. So how to get the 10-year yield down? Not with rate cuts, obviously. That flopped and had the opposite effect. But with a three-pronged strategy.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

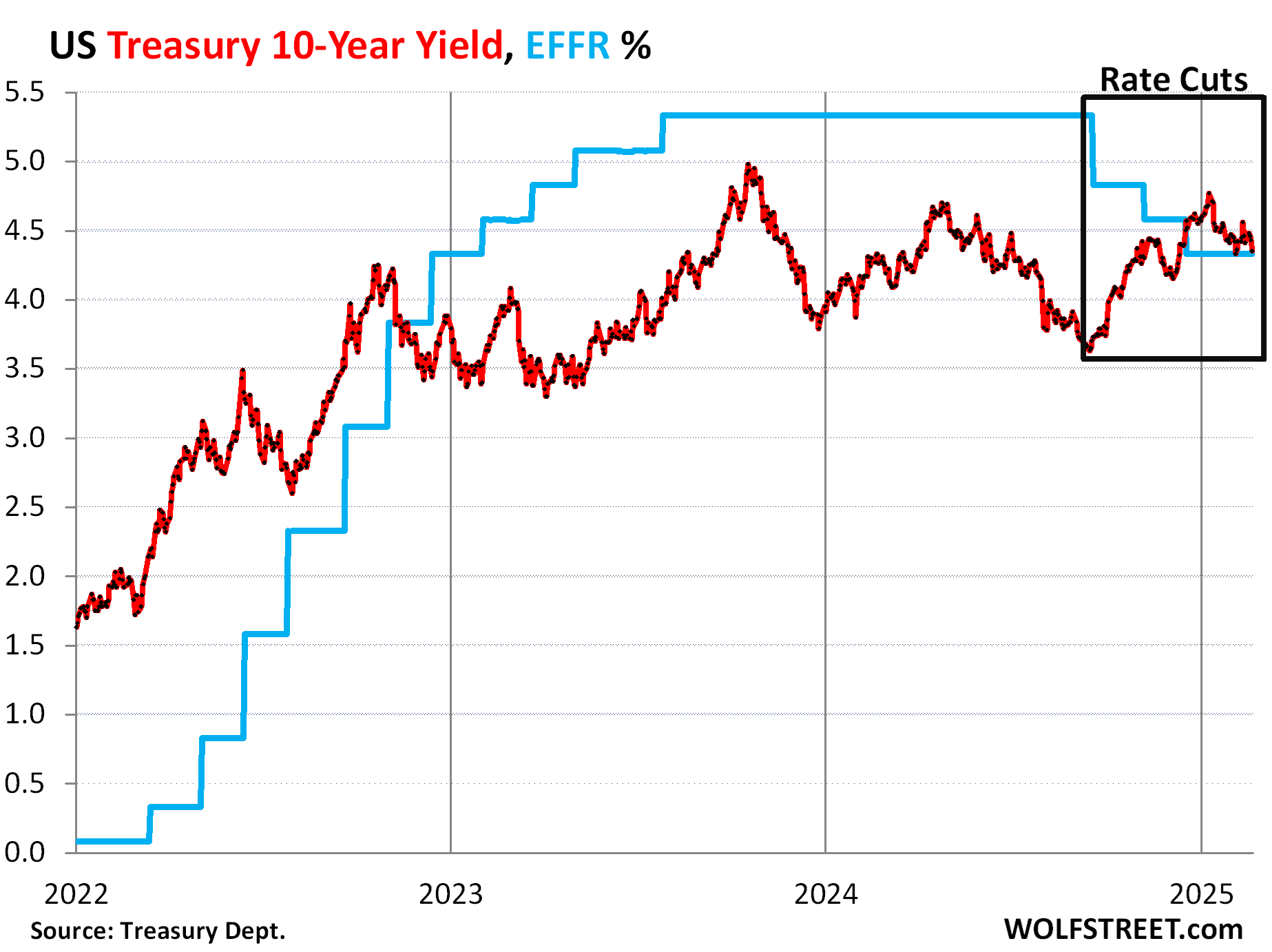

The 10-year Treasury yield dropped by 8 basis points on Friday, to 4.43%, perhaps inspired by iffy feelings elsewhere as stocks careened lower and investors sought safety.

Since January 10, the 10-year yield has now given up 34 basis points of that 114-basis-point spike that it had experienced from mid-September 2024, just before the Fed’s first cut, through January 10, 2025. Over this period of surging long-term yields, the Fed had cut its short-term policy rates by 100 basis points.

The Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR), which the Fed targets with its policy rates, has remained at 4.33% since the December rate cut, down by 100 basis points from the pre-cut levels (blue).

One of the reasons for this massive disconnect was the market’s assumption that the Fed, amid its rate cuts and rate-cut talk, would be lax about inflation, which just at the nick of time had started to re-accelerate. And further rate cuts could provide additional fuel for it. Rising inflation and a lax Fed spook the long-term fixed-income market.

Long-term yields really matter to the economy. They reflect the borrowing costs for businesses and households. There is some debt with floating rates, but the majority of the debt has fixed rates that track 10-year Treasury yields, and higher 10-year yields would increase actual borrowing costs for new debt in the economy and tighten financial conditions and eventually slow the economy.

These rate cuts, and the formerly-projected future rate cuts, in light of the inflation scenario developing over the past few months, had the effect of spooking investors who wanted to be compensated more for those higher inflation risks over those 10 years, which pushed up long-term yields.

So how to get the 10-year yield to go down?

Not with rate cuts, obviously. That flopped and had the opposite effect. But with a three-pronged strategy:

- The Fed gets more hawkish about inflation and puts further rate cuts on ice.

- The Treasury Department minimizes the supply of long-term Treasury securities, by shifting issuance to short-term securities, which it has been doing for over a year; and by deficit reduction, which is new.

- The Fed and Treasury Department both talk down the 10-year Treasury yield.

So the Fed got more concerned about inflation at the December meeting, when it cut one more time, but projected only two cuts in 2025, and saw higher inflation and higher “longer run” rates. At the January meeting when it didn’t cut, the Fed pivoted to wait-and-see and put further cuts on ice.

Then on February 6, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent came out and said in an interview that “The president wants lower rates,” but that “he and I are focused on the 10-year Treasury and what is the yield of that.”

So lower long-term rates. And how do you get long-term rates down? Get inflation down and keep it down. And that’s the Fed’s job. And rate cuts won’t do that job. The Fed cannot be lax about inflation, that became abundantly clear, because a lax Fed in an inflationary environment would drive up long-term yields.

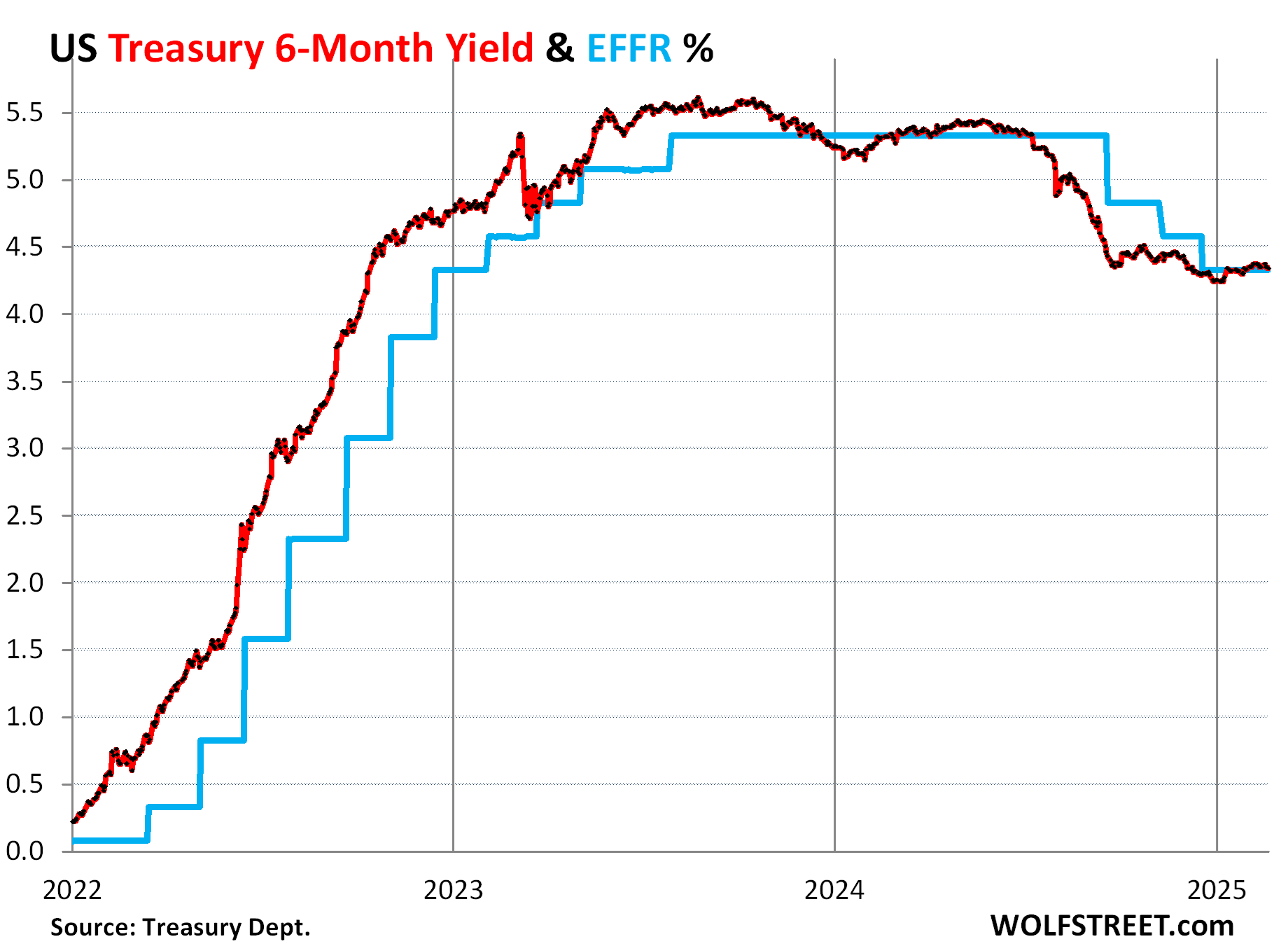

Short-term yields stayed put.

Short-term yields essentially haven’t budged since early December when they had already fully priced in the rate cut at the time.

The six-month yield no longer prices in any rate cuts in its window through mid-2025 before it matures, hovering right around the EFFR.

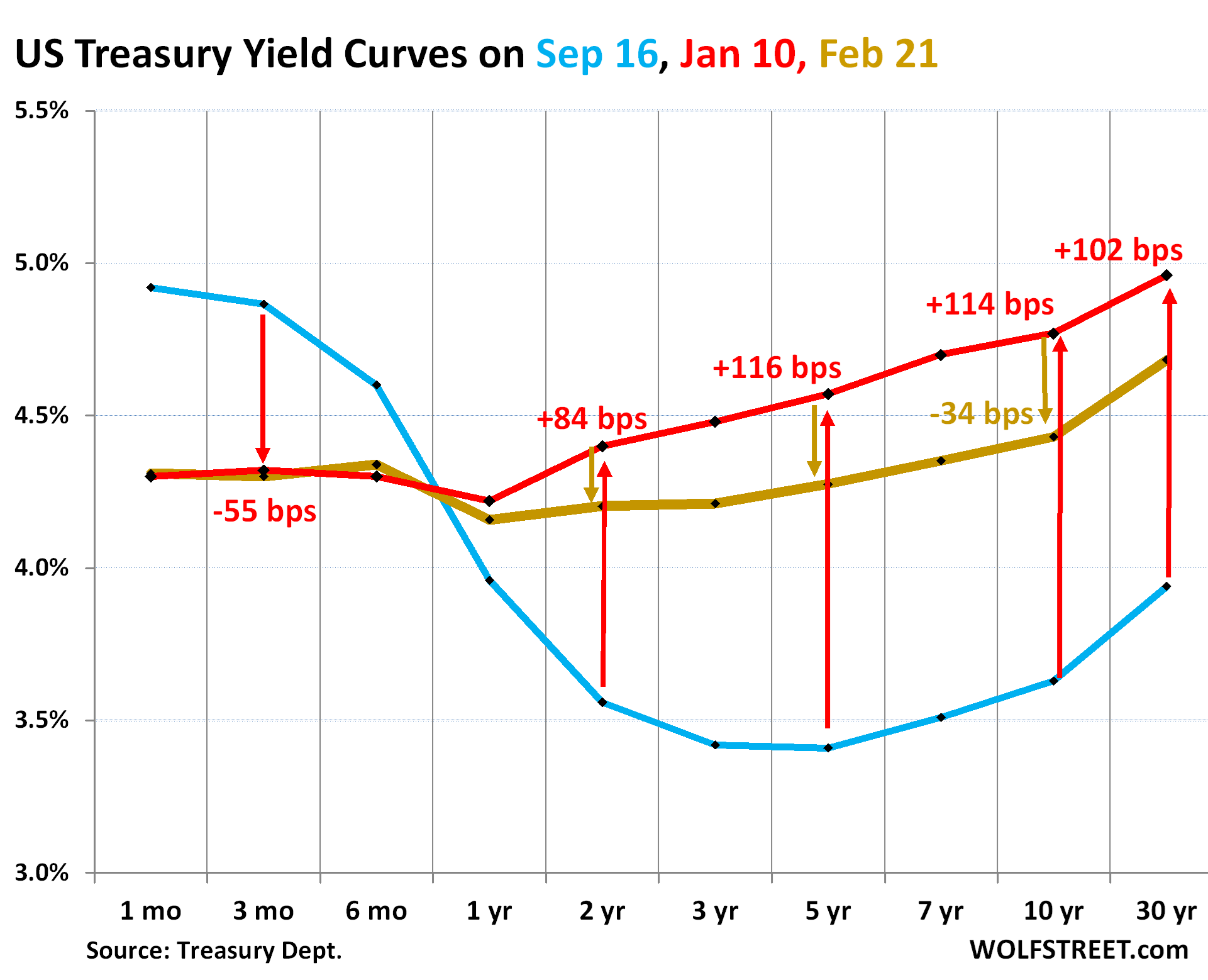

The yield curve flattened.

With the Fed having put rate cuts on ice, short-term yields stayed put at around the EFFR, while long-term yields came down some. As a result, the yield curve flattened some.

The chart below shows the yield curve of Treasury yields across the maturity spectrum, from 1 month to 30 years, on three key dates:

- Red: January 10, 2025, just before the Fed pivoted to wait-and-see.

- Gold: Friday, February 21, 2025.

- Blue: September 16, 2024, just before the Fed’s rate cuts started.

This yield curve has a dip at the one-year yield, with the 6-month yield being higher than yields in the range of 1-5 years.

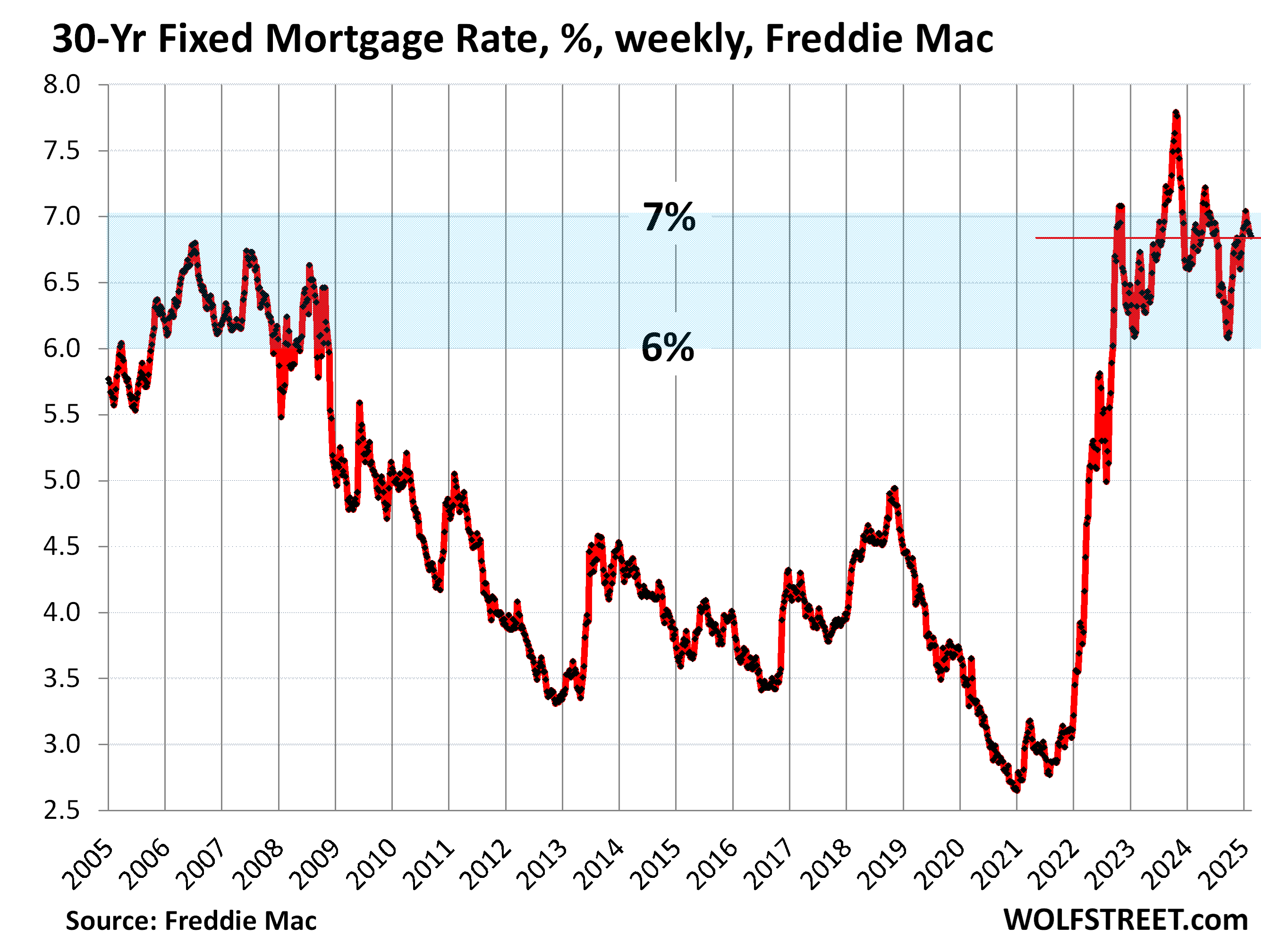

But mortgage rates remain close to 7%.

From the initial rate cut in September through mid-January, just before the Fed pivoted to wait-and-see, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate had risen by 96 basis points, to 7.04%, according to Freddie Mac’s weekly measure, while the Fed had cut by 100 basis points.

Mortgage rates have since given up only 19 basis points of this 96-basis point surge, and at 6.85% are at the upper end of the 6-7% range in which they have been since September 2022.

Over the three decades between 1972 and 2002, 7% was the lower edge of the range, and for most of that time, rates were above 8%.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Savers can’t catch a break.Most yields now on savings& CDs are below 4%.

It’s obvious inflation isn’t dead,but a 5% savings rate is.

T-bills are still over 4%. Many money-market funds are also over 4%.

Banks are here to rip you off if you let them.

Today’s problems are the results of too much liquidity from irresponsible unnecessary fiscal spending by Schumer, Pelosi, Biden

(approx. 7 $trillion from 2021 to 2024) and irresponsible monetary policy during pLandemic. Probably all well devised by CCP.

So congrats to them on their success. But are they truly prepared for All the ramifications?

LOL, is your memory so bad or so tainted that you forgot the other half? In the 4 years from Jan 2017 through Dec 2020 (Trump 1), the US debt exploded by $7.7 trillion, or by 38%, from $19.9 trillion to $27.6 trillion.

Tim,

There might be some hope for the working class give up the us versus them in who is less responsible. Neither side really cares about anything other than staying in power and dividing what could be, with perspective, a unified class struggle to something better. This is not some abstract concept but a simple recognition of doing the right things in a society(health care, education, secure retirement, food security, shelter and so on). Not exactly like we don’t have the money if the correct priorities are choosen.

Both parties have been wildly irresponsible with spending, one a little more than the other to be fair, but you can lay the blame for inflation, especially as it relates to housing, squarely at the foot of the moronic Fed, which inexplicably bought massive quantities of MBS as home prices rocketed up 40%, literally the dumbest thing I have ever seen for an agency supposedly created to stabilize the currency.

President Debt Increase Debt Increase %

Ronald Reagan $1,604,482,712,041.16 160.8%

George W. Bush $4,217,261,484,712.34 72.6%

Barack Obama $7,663,615,710,425.00 64.4%

George H.W. Bush $1,207,189,695,334.34 42.3%

Richard Nixon $121,339,561,890.14 34.3%

Donald Trump $6,700,491,178,561.60 33.1%

Jimmy Carter $208,861,000,000.00 29.9%

Bill Clinton $1,262,689,326,747.48 28.6%

Joe Biden $4,738,415,474,674.48 16.7%

Getting old isn’t the glorious journey actually experienced as opposed to the exaggerated version expressed by the funerals key note speaker.

This is a time when the brave object.

The stock market is in record territory daily therefore there is no precedence for a sudden revaluation which, frankly, the administration is hell bent on bringing about.

The 10 year bond seems overvalued to me. The risk premium seems an after thought. The 10 year is priced by the private market, though, a pretty savvy bunch.

TXRancher,

If the national debt was approximately $28T when Trump left office in 2021 and over $36T when Biden left office last month, then the $4.7T figure for the increase in debt under Biden appears to be incorrect. I did see an Investopedia article with the figures you presented for each president, but it goes on to say the national debt increased by $8.4T under Biden. That is consistent with what we know about the national debt.

The apparent inconsistency may be explained by Investopedia’s methodology. The Investopedia article notes that a president has very little influence on the national debt during their first year in office. Therefore the figures you presented “are based on U.S. fiscal years that most closely align with a president’s inauguration” according to Investopedia. The article will need to update Biden’s figures when the current fiscal year ends on September 30 in order to compare apples to apples. It also means that any additional debt from stimulus programs implemented immediately after Biden took office in 2021 are attributable to the previous Trump administration. I think this context is very important to understanding the figures you presented.

Someone who uses the term “Plandemic” deserves the same treatment you would give someone wearing a tinfoil hat carrying a sign proclaiming the end of the world. It’s jarring how many lunatics are out there.

First and Long,

I missed the “plandemic.” That is normally cause for deletion of the entire comment. Apologies for the dereliction of my duties.

1 year CDs are 4% at my local credit union, down from 5% last year. So I’m breaking even with inflation.

Have you looked into bitcoin?

/s

Not after you pay taxes on the gains.

Well treasury direct is a better option than the local credit union if one is riveted on maximizing their instantaneous financial rather than the long term commitment to the community.

Re-institution of QE would increase the value of the long term bonds significantly. At the moment, I think, Trump’s go to was QE, Tax cuts, the ejaculation of covid money to the business community. The greatest trade deficit experienced up until then.

Vanguard… brokered cd’s

you could always buy Turkish 10yr Treasury Bond at 27.38%

The DFIs could continue to lend even if the nonbank public ceased to save altogether. I.e., savers never transfer their savings outside the commercial banking system unless they hoard currency or convert to other national currencies. The elimination of Reg. Q ceilings was a pyrrhic victory. I.e., the NBFIs are the DFI’s customers. An increase in bank CDs adds nothing to GDP.

The last thing that’s in danger of shutting down is the US government infrastructure.

America is a beautiful entity, like the old narwhal with barnacles attached. Although Rome lasted 1000 plus years, by which standard one judge America as a young empire as empires go.

It is the people that make this mix. The magic that formed the basis of a social democratic Republic. And endures to this day.

Please stop the doggies from tearing up the furniture.

Retail savers who don’t care are getting sub 4% rates.

It’s trivial to search for over 4% for FDIC insured savings accounts CD & savings accounts from banks you have heard of and those you haven’t. Like on doctor of credit.

Add on top of that MMAs from all the brokerages, including the ironic communism for capitalists Vanguard, it’s trivial to get MMAs based on treasury products or just buy t bills from Treasury direct.

Heck, I have check writing privs and unlimited ATM access to handle my checking needs on fidelity through its MMA based on tbills.

A lot of retail savers don’t do it right.

it’s trivial to get MMAs based on treasury products or just buy t bills from Treasury direct.

Not so trivial for the people you are ranting against for their ignorance about the government guaranteed short term interest rates that may be 15 basis pts more. Trying to time or game a market is a fools errand.

Personally, I’m in T-Bills. I’m not about to bail wall street out of their overpriced stock.

I used to think the Eccles Bank was a force for good in the world economy, until I figured out all 1,000 PhD economists do there is cook the books.

All I ask for that in my next life I am a fruit fly in the CEO’s office of SVB Bank when he got that call that 25% of the banks asset was being pulled by Peter Theil & friends. Just to see the look on his face.

I have a theory on bankers. It’s that they dumb. It sounds crude, but that was also Michael Lewis’s assessment of Bank of America’s CEO in 2008.

They are dumb Wolf. My 13 year old is a better Risk Officer than what SVB had.

Just imagine what your 13-year-old would do if he is paid 10s of millions of dollars a year to take huge bet-the-farm risks, knowing that he will get to keep that money if he blows up the farm after a few years.

I too miss 5% risk-free yields, but you can still get 3.7% from Capital One’s liquid savings account, and SGOV is still 4.33% which I use as my “cash” account with my brokerage.

My cheapskate credit union stopped paying anything on their savings accounts a few months ago, so I’m keeping as little in there as possible (except a 4.5% 6mo CD I took out last Nov – suckers!)

Chasing yield on CDs and bank accounts isn’t worth it. Do yourself a favor – Treasurydirect.gov. Easily roll Tbills and move money to your checking account in a couple days if you need it. Anyone sitting on six or seven figures of cash should stop goofing around with banks and sleep quite a bit better at night.

Wolf – great chartsbas always – would you mind including the 20Y long bond on the UST yield curve chart?

Except for low balance checking accounts, I quit banks and moved to T-bills two years ago and have not looked back. I buy them through my broker Schwab (I am not advertising Schwab, they have their pluses and minuses, but I eventually learned how their system works to my advantage, so they are okay). T-bills pay the highest rate on 3 month governments, 4.31%. Plus you don’t pay state tax on interest (a big deal if you live in a high tax state). The highest 3 month CDs on Schwab pay 4.35%, but you pay state tax on the interest. There are some non-broker CDs from boutique banks that pay higher, but you have to spend a fair amount of time searching for them, and don’t forget you pay state tax on the interest and an early withdrawal penalty if you need the money fast.

I like to stay liquid, Treasury Direct will not let you sell through them (you have to transfer the funds to a broker), and CDs always have early withdrawal penalties, some draconian. Banks are not your friends. Finally, ACH-ing money to or from my banks to Schwab is accomplished overnight. Just meet the cut-off times when ordering.

BTW, to ShortTLT, SGOV has a .09% expense ratio, which is pretty low, but if you have a lot of bucks, it makes more sense to buy 1 to 3 month T-bills. They are just as liquid, only a little more complicated to deal with. You also have to buy T-bills in $1000 increments at brokers. As a parking space for low balances, as you say, SGOV is probably okay.

Ol’b,

Your correct. But…

1. They don’t teach that in Finance school.

2. Wall Street would lose their minds if 1% of their customer base did this.

Ol’B – I own those exact same Treasuries indirectly via SGOV, but without the liquidity issues of owning T-bills directly. I can also buy SGOV in increments of $100 instead of $1000 like with T-bills. I used to ladder bills but this works better for me.

And as far as chasing yield goes, cash is only 10% of my portfolio, which overall should return consistent annual dividends of about 10%.

thurd2 – how often have you sold your T-bills before maturity?

I have Merril for my nonretirement brokerage, and during the recent cutting cycle, I ran into restrictions that prevented me from liquidating certain CUSIPs. Basically, they set an absurdly high minimum sell order ($100k+) so I had no way to sell them.

Even tho I was laddering and frequently rolling over, the lack of liquidy made me start rolling them into SGOV instead. I didn’t want to be in a situation where I couldn’t liquidate, even though I always try to hold till maturity. SGOV also saves me the hassle of rolling over (going into the fixed income screener and finding the highest yielding CUSIP that doesn’t have a $100k min buy…).

I’m not trying to hold a lot of cash in this account, and SGOV is just subbing for a cash sweep (which Merril doesn’t have).

Why do that when you can buy treasuries and don’t pay state income taxes

if you’re getting below 4%, you’re not trying hard. raisin is a platform that has plenty of savings accounts above 4%, and just from a google search, i see that openbank, a santander affiliate, has 4.75%.

A lot of people suffer from age related decline which I think is one of the most profitable lines of business for the big banks which have been accused by others as a shady enterprise.

Buy individual muni bonds that are investment grade with yields that are ~4.5% tax free, which is the equivalent to over 6% taxable depending upon your individual federal tax rate. And most have call protection until 2033.

Also they are quite liquid and you can sell them at anytime.

Franz and Bill, you should provide us with the terms (1 month, three month, 1 year, etc.).

There are sizable transaction costs with individual bonds and the market is not as liquid, and the rates you are describing are above the market for high quality short term muni bonds, like 100 basis points higher.

“Buy individual muni bonds that are investment grade with yields that are ~4.5% tax free”

I’m calling BS on this. Muni bonds usually yield LESS than treasuries & agencies due to the tax advantages.

The CAGR of the money supply (m2) has been 7%/year long term. So unless your investments earn that after tax you are losing real value.

M2 is worthless. The accounts it includes and excludes make it useless. It’s completely outdated. Base your decision on a screwed up worthless metric at your own risk.

What are the proper metrics to use for money supply / monetary debasement?

It’s not money supply that is the problem, it’s artificial money supply created by central banks that’s the problem. So we watch the Fed’s balance sheet for that.

A growing economy with profitable businesses naturally creates “money.” And destroys “money” when things turn really bad. That’s part of an economy. And that’s not the problem.

I’m not too surprised 10Y+ yields took a break from rising – they needed to. However I don’t see how they can stay this low:

1. Short term yields aren’t going lower anytime soon, and with the YC this flat, there’s barely any term premium. Eventually bond investors will want more compensation for duration.

2. Bessent is looking to normalize Treasury issuance, which (as I understand it) means fewer bills and more coupons. More supply = higher yields.

No problem though, good opportunity to start buying some TLT puts again.

Bessent was critical of Janet for not issuing longer dated treasuries before getting the job, but his most recent statements are that they won’t issue on the longer end for a while. I thought the same as you until his tune has now changed. Funny how being a critic vs having to actually make the decisions changed him.

“his most recent statements are that they won’t issue on the longer end for a while”

Thanks for the correction – I wasn’t aware he changed his tune.

The Fed hinted at stopping QT soon. Summer probably.

They are going to continue to roll off MBS and probably start BUYING Tbills again to maintain relative balance sheet size. The Fed could potentially buy $200-300B of Tbills annually, and it won’t be QE.

If the deficit is reduced by 50% and the Treasury shifts duration to the 5-10Y range, and the Fed Hoovers up all the Tbills more or less, everyone else will be forced to go out on the curve. Long rates will DROP in this case. A deficit of $1T with the Fed buying up to 30% of that doesn’t leave much for everyone else. Global demand for UST is always strong.

“The Fed hinted at stopping QT soon. Summer probably.”

Not quite. They hinted at “slowing or pausing” QT if the coming debt ceiling fight starts messing with the reserves, which it can do.

Wolf, is pausing QT still a desirable outcome if the debt ceiling fight does mess with the reserves? In your opinion, how long would too long be for a pause? In my uninformed view, slowing the pace of QT makes sense on its face as opposed to a pause.

Withdrawing liquidity is risky and can be messy. No one has ever withdrawn that much liquidity. So there is no playbook. There is now close to $800 billion in the government’s checking account (TGA) at the Fed that is going to get drawn down during the debt ceiling, to maybe near nothing, and that’s not a problem. The problem the Fed pointed at is when the TGA is down all the way, and the debt ceiling gets lifted, then the government has to go on a borrowing binge to refill the TGA. SO cash leaves the banking system to buy T-bills from the government, and reserves (cash that banks put on deposit at the Fed) might drop sharply. So at that refilling stage is when liquidity shifts from reserves (draws them down quickly) via government sales of T-bills to the TGA. It’s the refilling stage after the debt ceiling gets lifted – that potentially sudden and massive drawdown of reserves – that the Fed is worried about. At the end of the last debt ceiling fight, ON RRPs were suddenly drawn down because of the shift (cash shifted from money market funds to the TGA), and that was fine, but now ON RRPs are nearly gone, and so the refilling of the TGA might come out of reserves in an unpredictable manner. That’s what the Fed is worried about.

For example, if reserves plunge by $500 billion in a month, that’s a lot. That’s on top of the drawdown from QT. I don’t know if that would cause a problem, but I can see that they’re worried it might cause a problem. The way to continue QT for as long as possible is to avoid causing a problem – that’s what the Fed speakers said multiple times over the past 12 months, including Logan, and I agree with that. If something blows up, QT ends, and that would be too bad. So I’m on board with trying to avoid a blowup in order to continue QT for as long as possible.

I know that doesn’t sit well with some people here who want to blow everything up now, especially the banking system, I mean, rip off the Band-Aid and get it over with, but obviously, that would start all the shenanigans all over again. The trick is not to blow anything up while doing QT.

Super illustrative. Thanks Wolf. So a strategic pause around the timing of debt ceiling discussions wouldn’t be the end of the world. MBS would roll off in the background and an extra ~$40B of liquidity stays in the system. Is this correct?

I’m basing $40B off of your wonderful Feb 6, 2025 article titled “Fed Balance Sheet QT: -$42 Billion in January.”

Wolf,

Replying to both comments about the details of why the Fed would want to slow QT in response to the TGA drawdown.

Maybe you could do a full article about this? With the implications and interconnectedness to reserves etc.

I remember reading about all the reverse repo issues back around 2019/20, but I’m a bit rusty on the ins and outs of all these operations and how they function together.

Just a thought.

As always, thanks for all your work!

-Bio

Biorganic

All we have right now is the reference in the minutes. If this is something they will actually do, there will likely be public discussion, such as by Dallas Fed president Logan who is the nuts-and-bolts expert in that bunch.

I just think it’s way too early to discuss this. If the debt ceiling gets lifted in a month or two, the entire issue will go away.

Can you do a full post on this because I don’t understand this. They still have $7 trillion dollars on the balance sheet (if memory serves me correctly) which seems like more than enough room to continue QT. If they really can’t continue QT, then that would likely mean hiking rates again, and given the feds string of mistakes, might be what finally drives a recession.

This article will help you understand the fundamental part of this issue — the liabilities of the Fed’s balance sheet. Reserves are one of the four big liabilities. It’s reserves we’re talking about here, currently $3.27 trillion. And reserves cannot go to zero. They represent essential liquidity in the banking system. But they can go a lot lower.

https://wolfstreet.com/2024/03/23/the-feds-liabilities-how-far-can-qt-go-whats-the-lowest-possible-level-of-the-balance-sheet-without-blowing-stuff-up/

Ah, that makes sense. I guess it wouldn’t be worth an article if it’s not even happening, although the theory and concept is still interesting to me.

Thanks Wolf!

I’m sure you’ll keep us posted, as always.

Tlt puts

Don’t underestimate Trump and economic health could be we get lower 10 year by higher FFR slowing economy

“could be we get lower 10 year by higher FFR”

I don’t see how the yield curve could re-invert i.e. return to an unnatural state.

Yeah, rates should head higher in April.

Look at a 3 or 5 year chart of TNX. it is well into bullish territory for yields if you focus on rising yields. I’m guessing the big money is timing these TNX mini bond rallies….scalping for a couple months. Retail “investors” will be left holding the bag when the TNX hits 6%. Thus the plethora of “now is the time to buy bonds” articles on MSM financial sites.

Yeah, the yield is pulled back to a pretty major support, with the daily RSI as low as it’s been all year (since “rate cut mania” in Aug/ Sept).

The chart went nearly vertical after the cuts began!

The presence of a “secular bear market” in bonds is nearly palpable, if not completely unbelievable (by a generation that believes 4% is a record yield).

“Where are the correlations?” is the question I have been asking.

Can we escape retribution for over a decade of excessive monetary stimulus? Excessive inflation (and higher-for-longer rates) and/or excessive unemployment must surely follow, after the “Bernanke” decade. (Probably both — though sequencing will depend on our befuddled central bankers and the gullibility and fears of bond market participants.)

The world thirsts for an honest, reliable and brave monetary authority. Anyone seen one?

Except neither excessive inflation nor unemployment has followed. I don’t like higher prices any more than anyone else, but 4% is nothing in the face of the massive stimulus we had.

“Higher for longer rates” have just (partially) reverted to the historical mean.

Frankly the job this Fed has done so far is pretty remarkable. Nobody is bitching about the massive recession we didn’t have.

I wouldn’t give the fed that much credit. They failed at their job controlling inflation and still havent reached their target. I see first hand how the cost of living is destorying poor communities each day.

Let’s not forget that they broke the RE market with ZIRP. As Wolf has pointed out, there is not really a shortage of housing – things didn’t suddenly change when covid hit. But there is a large imbalance of homes and multifamilies that are reasonably affordable for the people that would like to live in them or rent them out affordably. And the Fed + stimulus broke that.

No, Powell was ignorant:

Powell:

#1 “there was a time when monetary policy aggregates were important determinants of inflation and that has not been the case for a long time”

#2 “Inflation is not a problem for this time as near as I can figure. Right now, M2 [money supply] does not really have important implications. It is something we have to unlearn.”

#3 “the correlation between different aggregates [like] M2 and inflation is just very, very low”.

M2 of course, includes savings/investment type of accounts which have very little turnover, or punch. Transaction accounts on the other hand turn over 99 times faster.

DRG,

I somewhat agree with you.

The FED are geniuses in preventing a housing crash like 2007. They gave every homeowner a 3% escape hatch back then which prevented massive selling before they drastically increased rates.

They prevented a multiply predicted recession during COVID.

My 2 criticisms of the FED are:

1) They are too slow in becoming conservative. They react years after they should with raising rates slowly (and panic when inflation is out of control.) and turn on a dime when lowering rates or implementing QE. People think the Fed will bail them out of reckless decisions. The US government is worse with extending COVID handouts and forbearance too long after the crisis had ended which caused inflation.

2) Why in the heck was the Fed buying MBS when the housing market was already bubbling?

I am speaking by looking in the rear view mirror but I thought this late 2021 when the Covid vaccines were fully available.

BobE-

Re: your comment “The FED are geniuses in preventing a housing crash like 2007.”

I wonder if you meant to say “postponing,” rather than “preventing?” Postponement is transitory, but prevention is forever…

Your comments on timing and over-reach are right on, though.

They aren’t bitching about the recession, for now, but plenty are bitching about inflation, high wealth concentration, speculative excess, and capital favoritism. We are facing a deep socital recession, which is much worse than any cyclical economic recession.

Bobber,

None of this is new as has been moving in this direction since 1970s. It is just the will and sacrifice needed to confront it is less appealing than the table scraps provided to keep everyone appeased. Fairly interesting to watch it unfold. Clearly a shift is occuring, from what I can tell among the younger generations but interesting to see how that holds up and what influence it has long term.

“The job the Fed has done is pretty remarkable”? If you mean remarkably incompetent, then I agree.

Buying hundreds of millions in MBS while home prices go up 40%? There isn’t a single reason they should have even started that, and it should have been terminated immediately when home prices started to rise. Remember, “taking away the punchbowl” and all? They kept the punchbowl going. Pure stupidity.

Remember “transitory”? I do. An agency who’s job is to stabilize the currency stabilizes the currency, they don’t light a bonfire and watch it burn for a year

We’ve had going on 4 years of inflation higher than their bogus illegal 2% target. Prices are 30% higher. This is a massive failure.

“There isn’t a single reason they should have even started that”…unless you believe like I do that the FED works for Wall St. exclusively.

They screwed a lot of pension funds to save the banks. That damage has yet to fully appear.

I blame fed for the housing mess we are in locking young families out of housing market for ever

Killing American dream is not something I can personally forgive fed for but who cares about me

High stock market vs high housing prices two different things

“The way to crush the bourgeoisie is to grind them down between the millstones of taxation and inflation.” — Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

I think our “bourgeoisie” are doing fine, our proletariat, however, are the ones being ground down.

4.5 trillion in tax cuts will increase the deficit and require higher treasury yields and cause higher mortgage rates.

All true, but it would also be even more helpful if spending were cut back closer to the 2019 baseline literally 30% lower than now.

Adjust that for inflation. That’s more like 10% lower, not 30%.

BUT 2019 spending was thoroughly bloated, too.

All,

Now available from TreasuryDirect:

six-week T-Bills.

Is this an effort to skooch down

short term funding cost by attracting

more “warm” money?

J.

————————————————

I’d prefer something shorter than

4-week. Especially if the yield curve

is this flat. How abut a one-hour

T-Bill, for that really hot money?

Put your money in a MMF and you’re indirectly loaning to the repo markets.

Lowering the 10-year treasury yield, without lowering inflation? Or lowering the mortages rates, without lowering inflation?

The fed could always restart QE. If the Fed buys up 10-year treasuries and MBS, and rates are likely to fall, no?

Or just pause QT. QE is too much and leads to increased home prices.

The fed and other central banks can only manipulate long rates for the short term. As a suggestion for others, look at other treasuries around the world and watch what they are doing with relation to the 10 year US treasury recently. They are magically falling temporarily except Japan who currently has a major inflation problem that is getting worse and has a 10 year treasury that has ripped to the upside since September and it will go higher from here with their recent nasty inflation reports that keep getting worse.

Watch what happens with just 1 more red hot US inflation report next month. Just 1 more. You are going to see a massive uturn in the 10 year US treasury once again with hot inflation.

Future inflation will dictate where the 10 year goes. If inflation gets unanchored again……. Trump, the Fed, and everyone else can talk as much BS as they want. But talk is cheap. More Hot inflation month over month and year over year will rocket the 10 year higher, guaranteed. And in time, the 10 year getting high enough will eventually break the back of both the stock market and the real estate market along with the credit market. My prediction is, its coming. The BS “transitory” inflation wheel can only get spun so many times before things start to break because of inflation.

“Watch what happens with just 1 more red hot US inflation report next month.” BLS/BEA layoffs?

” If the Fed buys up 10-year treasuries and MBS, and rates are likely to fall, no?”

Inflation would explode.

Isn’t that the point of “interest rate repression”?

Inflation and nominal GDP explode, but bond yields do not, so “debt to GDP” goes back down to the “good” range while the bondholders get wiped of their real value?

That’s when investors stop buying bonds. It’s that simple. You need to understand yield. If the yield is too low to compensate for inflation, because the government wants to repress it, investors don’t buy. Who is the government then going to sell those bonds to? To the Fed, with inflation raging already? That will blow inflation out all proportion. Yeah, that will reduce the burden of debt, but it will wipe out real wages, financial markets, and asset holders, because there won’t be anything that can keep up with that kind of inflation. And the economy will suffer for years. When investors refuse to buy the government’s bonds, there are no more good choices left. Everything is bad. There are lots of examples in history of that.

Personally, I am not buying long-term treasuries (10, 20, 30 year) because the yield is currently too close to 1 to 3 month treasuries. I am going to need a lot more than 31 basis points (20 year minus 3 month yield) or a measly 13 basis points (10 year minus 3 month yield) for inflation risk.

I don’t know why anybody would buy a 10 year instead of a 3 month now unless they believe there will be much lower average inflation over the next 10 years (good luck with that) , or if they are forced to buy 10 years for some legal or business reason.

Thurd2-

There might be a reason to buy 2-4 year paper. “Reinvestment risk”? That’s the risk that yesterday’s 5% T-Bill demonstrates when it matures today in a 4% world. Crawling out a bit on the yield curve LOCKS IN a known rate of income, rather than leaving next year’s rate to the vagaries of the market.

This is especially true for those who live of their investment returns.

Risk comes in many flavors.

Cheers

Should have said “….for those who live off of their investment income.”

“Crawling out a bit on the yield curve LOCKS IN a known rate of income”

The flip side of re-investment risk is opportunity risk.

You’re locked in at 4% for a couple years, meanwhile rates went UP and you’re now underperforming the rest of the market.

You might say “I can live off 4%” but if yields are going up in response to inflation, and all your costs are going up…

Costco has Prime T Bone for a mere $29 lb.

Hamburger now at previous T Bone price/lb.

Local eatery(been dining there 42 years) has seen prices rise for my favorite fresh ahi fish and chips from $10 to $15 from 83 to 2020. Now $25 and heading higher every month. I see more folks splitting meals, which was rare prior to the good ship Bitanic setting sail. I suppose that’s more effective than Ozempic.

Raise you’re hand if you had not already expected/desired the content of this article 6-12 months ago.

As usual, the FED is at least a year behind the rest of us. And I don’t believe it is due to incompetence, do you?

Hmmmmm

HUH? Haven’t read my inflation articles here??? A year ago, the Fed’s rates were still at 5.25-5.5%. And it was still in wait-and-see mode. But then inflation cooled a lot over last spring and summer and got close to the Fed’s 2% target in June, with the PCE price index at 2.1%, and core at 2.6%, while Fed rates were still 5.25-5.5%. That was a historically high positive real EFFR. So it made sense to cut, given how low inflation was at the time, and the trend it showed. But then inflation started accelerating in recent months. So it makes sense to wait and see. PCE inflation is now at 2.6% and core at 2.8% and the Fed’s rates are at 4.25-4.5%. If inflation heats up a lot, the Fed can hike again. If it cools back toward 2%, the Fed could cut.

Yeah, after Americans rediscovered what inflation meant….and HATED it, the Fed has been pretty much driven by inflation directions.

So goes inflation, so goes the Fed.

Although I don’t see a flattening of the yield curves as much confidence in the Fed credibility as the bond market being uncertain on the economy. We’ll see if it inverts…although that indicator is not always right either.

It’s hard to put out a forest fire when the fire chief is in dry forest, setting new fires.

dropping 972m

“So goes inflation, so goes the Fed.”

Based on a decade or so of QE prior to 2022, I would have said “so goes the Fed, so goes inflation.”

Potato, potahto…

While the Fed has been very foolish for very long, the actions since March 2022 make a lot of sense. It is the eternally optimistic and trigger happy media that interprets the Fed actions in a manner that favors high asset prices and speculation.

In the past, low interest rates and balance sheet expansion did not cause inflation because wage growth was subdued and capital spending was low and households were deleveraging. This kept CPI inflation low even when money supply was increasing massively. But that changed after Covid and AI speculation.

Now we have capital investment and wage growth. So any aggressive Fed action should transmit to the real economy much faster than it has in the past. This also increases the risk of deflation because interest rates remain high along with debt levels.

All this is too complex to predict. Smarter people than me have failed.

Asset prices remain very high and inflation remains stubborn. So something will have to give. We live in interesting times. Will be interesting to see if Fed has the resolve for inflation if/when growth slows. History of the Fed provides no guidance. They tend to be wrong for all sort of reasons.

‘Over the three decades between 1972 and 2002, 7% was the lower edge of the range, and for most of that time, rates were above 8%’

Maybe explains most of the ‘odd’ stickiness of long rates: having gone through huge artificial manipulations to reduce rates, the market is returning to normal, and normal is not a three or four or five percent mortgage.

It’s easy to manipulate short rates because the risk is short. There is sometimes an ad on WS from a Canadian mortgage lender offering 2.9 %. I clicked on it: it’s for either 3 months or 6, forget which. A teaser rate. The 30 year offered in US is a different commitment.

New homes for sale near me in Texas (starter homes) are offering 4.99% – 5.99% teaser mortgage rates (2 years), then up to ~7% for the balance of the term.

Most likely the builder is just ‘buying down the rate’, kicking in the difference between market rate and the teaser rate. This is common.

Of course he could theoretically carry the mortgage himself, which is uncommon.

I am sure what the direction here is. 7% mortgage rates are here to stay. We are currently in the buying season.

Repricing has occurred since 2022 for homes. Food and energy have been most volatile in this period. Unless if congress can pass budget proposal, there is where we are at. The new treasury secretary issues more short term bills.

The system was destroyed further in 2021 when Yellen refused to change the way to pay our debt. If a republican house didn’t occur in 2022, we may as well would have said goodbye to America.

Yes the growth in debt was brought under control after 2022.

Jon Tester single handedly stopped the full impact of the proposed IRA and saved us all a couple of Trillion. Not that it wouldn’t have been better to have no IRA of course.

“So how to get the 10-year yield to go down?”

The telling thing is that “cutting deficits/debt” so as to reduce terminally stressed US risk premia isn’t even conceivable after 50 years of perpetual fiscal abuse (deficits).

In the end, the default/inflated fiat risk premia drives/will drive the 10 year Treasury rate.

The Fed can continue to print money/buy Treasuries so as to temporarily create an artificial, phoney baloney 10 year rate (see long night of ZIRP) but as we’ve very recently seen, that money printing creates inflation (shocker).

Counting on Fed money printing (essentially fraud) to save the US is, and always has been, doomed.

But the Established way of doing things (perpetual, and perpetually worsening, fiscal deficits) is so utterly entrenched, any alternative is inconceivable.

So we get a “Fed Cargo Cult” that ghost dances for some way/any way/magic obscure monetary lever/please-lord-just-one-more-time needle threading that will allow fiat printing to continue being the only imaginable fix.

But America’s creditors have been sold this bag of magic beans for 50 years – I think they’ve stopped believing.

So for *them*, honest open market creditors (not phoney baloney buyers from the Fed), the risk premia that must be applied against long term US Treasury debt is real and must be growing.

Sure the US won’t “default” – Fed printing/buying will see to that.

But being repaid loaned money in debased scrip, *with no end in sight*, ensures that lenders can’t view US Treasuries with anything but cynicism.

Wolf,

You say “minimiz[ing] the supply of long-term Treasury securities by… deficit reduction…” would help lower long-term rates. A corollary is that Trump and the Republicans might need to forego extending the 2017 tax cuts if they can’t rein in spending, right?

That’s assuming Congress will legislate in the best interest of the working class that elected Trump, which would benefit from lower interest rates and lower inflation. But the rentier class would benefit the most from lower taxes and higher interest income. So this is a test of Congress’s fealty to the working class or donors, right?

If the latter, Republicans might lower taxes regardless of what they do on spending. That’s what they did in 2017, with the (failed) promise that lower taxes would pay for themselves in higher GDP growth. That obviously didn’t happen. The deficits just kept going up. (Could the inflation of 2022 have been the cumulative effect of the tax cuts of 2017 plus pandemic-era deficits later?)

It looks like the flattening of the term structure since the inauguration of Trump might indicate that Mr. Market expects Trump will either, 1) succeed in reducing spending enough to enable passage of tax cuts or 2) will delay or forego tax cuts to lower the deficit? What’s your reading of the tea leaves?

A third explanation is also possible…..

A period of deflation sandwiched between inflationary periods.

6% 1-year GIC (CDs) are extinct right now in Canada. The highest is about 3.85% at some online credit union.

It’s like savers have to subsidize the Canadian housing bubble at all costs.

“It’s like savers have to subsidize the Canadian housing bubble at all costs.”

See also 80% ZIRP era in US, from 2002 to 2022.

In order to finance DC’s unwillingness to address the US’ rapidly worsening loss of intl competitiveness (see, China) the Fed strangled interest rates (see, money printing) in order to create 2 phoney baloney housing bubbles…for their (transient, oh so transient, “wealth effects”).

My Millennial cousin complained about a decade ago how “high interest savings accounts” were 0.05% pa at the Big 6 banks.

Seems like the response to 2007-2008 was to fuel Bubble I, and 2020 is currently Bubble II.

‘As of February 2024, the U.S. national debt was growing by about $1 trillion every 100 days, notes Wikipedia. This is equivalent to about $10 billion per day, or $416 million per hour.’

Since that was a year ago and the debt feeds on itself it will be growing faster now.

When Reagan took office. the accumulated DEBT since Independence, was one trillion dollars. In today’s context, the Fed actions or lack thereof are a bit quaint. They are competent but the most competent money manager can’t save a spendthrift movie star. Like the one who accused his manager of poor management, while spending 100,000 a month on wines.

There is a reason gold was up 28 % in 24, outpacing even the similarly inflation- fed stock market.

Gold has no relevance whatsoever financially, and 70% of the total amount of gold ever mined which is around 190,000 metric tonnes exists in the form of jewelry widely distributed around the world.

Re Gold, etc.

DC has spent 50 years relying upon the Fed to treat the USD more as scrip rather than a store of value.

50 years is enough to convince enough creditors that DC has, and never had, any other plan.

So here on out, it will be a never-ending hunt for escape hatches.

Most/all will have flaws/limitations – but the hunt will never stop unless the precipitating factor does.

And when Bill Clinton left office in 2021 the national debt was still under $6 trillion dollars. The money that Reagan had spent to defeat Communism caused an era of peace in which the national debt was able to be contained as the economy skyrocketed.

NOW the national debt is sitting at $36 trillion… and that is WITHOUT having to confront any existential threats to our nation since the Fall of the Berlin Wall. America’s problem with national debt has little to do with the 20 years that followed Reagan’s inauguration… and EVERYTHING to do with spendthrift Baby Boomer presidents/congresses/politicians of the LAST 20 years. In fact, the last politician that I can remember who was serious about debt reduction was Speaker of the House John Boehner… and his own party ran him out of town on a rail a decade ago.

“when Bill Clinton left office in 2021”

???

Maybe it was a typo and he meant Bill Trump, I mean 2001?

Wolf, I read an article that seemed absurd to me. Elon Musk wants to revise the gold reserve in Fort Knox and the minister of the finances is planning to sell it to finance the national debt. The conclusion of the article is that in this way the government will blow up the gold market but will pay off part of the debt. Gold reserves are said to be around $900 billion.

I would very much like to hear your opinion on this matter.

It’s absurd on its face. A quick google search says the current debt is 36.2 trillion as of Feb. 20. 900 billion would be a fart in a hurricane.

Why do people still read this stuff?

I expected such an answer lol, thanks!

🤣

Because Musk sent everyone an email saying read this by Tuesday morning or you will be considered terminated? ⚰️🛰️🙈

Careful, Wolf, the site that carries many of those “articles” also directs its readers to here! (presumably for the real/legit/decidedly un-psycho content)

The total amount of gold owned by the US Treasury is around 8,000 metric tonnes and only a relatively small amount is held at Fort Knox with the rest distributed around other US Mint facilities including West Point, NY. That has always been the case.

It is pretty easy to calculate the value of the US Treasury’s gold holdings based on there being approximately 8,000 metric tonnes multiplied by 35,270 ounces per metric tonne equals 282,160,000 metric ounces times $42.42 per metric ounce equals $11,969,227,200 total value of the US Treasury’s 8,000 metric tonnes of gold at the official price of $42.42 per ounce. At present market value of around $3,000 per ounce the total maximum value of the approximately 8,000 metric tonnes of gold would be around $846,480,000,000 ($846.5 Billion). In any event the US Treasury total gold value is less than $1 trillion compared to its nearly $37 trillion in federal debt so selling off all of that gold even assuming being able to get market prices wouldn’t do much at all to reduce the federal debt.

I think foreign purchases of treasuries is driving much of the movement in the 10year yield.

If you look at the tic data, they breakdown foreign purchases of long term treasuries by month by country since Feb 2023 . The average foreign purchases over that time are 38Bn per month. But if you take a 3 month rolling average of purchases, that drops to 6Bn in Sep 23, rates hit 5% the following month. By Nov they were buying 74Bn in one month, so the improved rates brought them back in, and rates declined again.

The next big drop was in Dec 2024, 3 month average down to 1Bn per month. Since Trump’s election, foreign countries have been dumping long term treasuries – they sold 34Bn in Nov 2024, and 47Bn in Dec 2024. Rates then climbed to 4.8% in Jan 2025. We will have to wait until next month so see the Jan tic data, but I suspect they started buying again in January once rates improved.

Why did they sell in Nov and Dec? Dollar strength to try to stabilise their exchange rates?

Who is still buying treasuries? Europe, Offshore finance centres, and Canada and Mexico since Feb 23. Who is selling – Brics, China mostly , but also India and Brazil.

Who sold in Nov and Dec? UK 37Bn ( a finance centre), Japan 32Bn, Brazil 27Bn, Caribbean (finance centres 21Bn), India 17Bn.

Looking at who holds loads of treasuries it seems to be countries the US has large trade deficits with. With the new administration’s policies it looks like their US trade will decline so they don’t need to hold so many treasuries, so onshore buyers are going to have to step in, or rates will need to go up.

In summary, trade policies look to be a major headwind to the goal of lowering the 10 year rate if they succeed in reducing imports, as major buyers of treasuries then look to become major sellers.

Rates need to go up. Very significantly.

The official valuation is at 44 US $ an oz or something like that. At market looks like 783 billion but since calculator doesn’t go that high anyone could check my math done on paper. There are 261 million ounces valued at 3K per oz.

$42.42 per ounce.

“As of June 30, 2024, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway held $237.6 billion in U.S. Treasury Bills (T-bills), surpassing the Federal Reserve’s holdings of about $195.3 billion as of July 31, 2024.”

Hmm, Buffett and I both like T-bills. Almost everyone says the stock market will eventually crash (down at least 20 to 30 percent), as it always does. Nobody knows when. I am surprised so many are willing to gamble on the stock market always winning, when you can get a no-risk state income tax free return of 4.3% with T-bills. The really big players will decide when to crash the stock market, and you will definitely not be in the loop. FYI, when the stock market crashed in 1929, it took 25 years and a world war for the Dow to get back to pre-crash levels.

Buffet and BH are so large that they don’t have as many options as small retail investors – hence the pile of T-bills.

Galbraith’s ‘The Great Crash’ describes how it took out the really big players: including the Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation, Ivar Kruegar, CEO New York Bank Charles Mitchell (arrested twice same day by competing cops)

Ten thousand banks went under.

The notion that the Crash was planned or engineered belongs with the ‘moon landing was faked’ file.

Big players compete among themselves, there are winners and losers, but mostly winners among the big boys. Some of the many survivors of the 1929 crash: GE, GM, ExxonMobil, Chevron, and more importantly, JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Citibank, Wells Fargo. Do any of those ring a bell? They were buying up the losers for pennies on the dollar. Recessions and depressions always favor the big boys in the long run. It is to their advantage to have them and, when necessary, initiate them. Ever wonder why Buffet is currently hoarding cash?

He’s patiently anticipating a train wreck.

Read yr sentence: ‘The really big players will DECIDE when to crash the stock market’

Yes there were survivors, GM did manage to remain profitable, as did others. US Steel survived although by 1934 at 10 % of capacity.

There is a difference between ‘surviving the crash’ and ‘deciding to crash…’

Bought for pennies? ANYONE buying in 34 was obviously buying for pennies, That was the price. How is this culpable?

An article appeared today about Buffet’s annual report, which supports my previous posts. I am not in love with Buffet, but he has a good track record. His current interest is in five Japanese conglomerates.

“The most interesting part of Buffett’s annual report is the balance sheet. Berkshire Hathaway’s holdings of cash and equivalents – mainly U.S. Treasury bills – has hit a record $345 billion, according to the latest figures. That is nearly twice the level of a year ago, and now accounts for a staggering 53% of the company’s net assets. It also exceeds Berkshire’s investments in tradable stocks, currently $270 billion. A year ago, Berkshire held nearly twice as much money in stocks as it did in Treasury bills.”

Buffet “is warning about the risks to America from “fiscal folly” and from “scoundrels and promoters” who “take advantage of those who mistakenly trust them.” “The American process has not always been pretty,” he wrote.

Capitalism is dog-eat-dog. The big dogs will eat the small dogs every time.

Buffet moving into cash because as he has said many times, ‘everything is overpriced’, has absolutely nothing to do with your statement that he or others will ‘DECIDE when to crash the market’.

Expecting a train wreck is not the same as causing one.

Maybe refer to a dictionary.

If you are driving a train, and you know it is going to crash but do nothing to prevent it, and even encourage it, then I would say you caused the crash.

When looking for suspects, the phrase “who benefits” is often used. As I mentioned, the big boys like to buy beaten down stocks for pennies on the dollar. Best time to buy beaten down stocks is during a recession or a depression. Ever wonder why Buffet is hoarding cash? He wants stocks to get beaten down.

Sometimes the big boys will step in to prevent an economic catastrophe. “The Panic of 1907 was a financial crisis that began in October 1907, triggered by an attempt to corner the copper market and exacerbated by a series of bank failures and runs on deposits. J.P. Morgan played a central role in mitigating the crisis by organizing a coalition of financiers and banks to provide liquidity and support to struggling institutions. He convened meetings at his home and directed efforts to stabilize the financial system, including rescuing the New York Stock Exchange from closing by securing loans for stock brokers and bailing out major brokerages.”

The following is from none other than the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Note the last sentence.

“The Panic of 1907 was a financial crisis set off by a series of bad banking decisions and a frenzy of withdrawals caused by public distrust of the banking system. J.P. Morgan and other wealthy Wall Street bankers lent their own funds to save the country from a severe financial crisis. But what happens when a single man or small group of men have the power to control the finances of a country?”

My point is, the big boys are calling the shots. They don’t want a complete collapse as 1907 almost was, but they are happy with the occasional recession or depression. But feel free to think what you want.

‘ J.P. Morgan and other wealthy Wall Street bankers lent their own funds to save the country from a severe financial crisis.’

In late Oct 29 JP Junior tried again. Pres of Exchange Whitney was sent out to buy stocks and bid for US Steel at OVER the quote. He then went on to the same for other key stocks. But this time it didn’t work. On Monday came the largest crash in history. The ‘big boys’ had tried to stop the Crash and failed.

Read Galbraith’s ‘The Great Crash’ and see if you still think the big boys planned it… OR didn’t try to prevent it.

Nick Kelly-

Good book recommendation.

In the same vein, House of Morgan by Ron Chernow provides interesting history and context. I’m guessing you’ve read it…

Nick, read my last paragraph:

“My point is, the big boys are calling the shots. They don’t want a complete collapse as 1907 almost was, but they are happy with the occasional recession or depression. ”

The big boys rescued the economy and essentially the capitalist system in 1907. 1907 was a very big deal, and led to the creation of the Federal Reserve Board. To repeat, the big boys don’t want an economic catastrophe like 1907, but are happy with the occasional recession or depression. Ever wonder why Buffet is hoarding cash?

hey Nick

How many bankers were prosecuted after the 2008 Wall St. caused liar loan crash in which 7,000,000 folks lost their homes and life savings?

Skeptical long side of the curve comes down if the best we can do is talk tough to it.

Also skeptical on doge and Trump getting the deficit down… Too much contradicting ideas. Like getting rid of the IRS and a 5k dividend check for the doge savings. It’s just silly

I expect rates to chop around and trend down before they shoot back up but we’ll see.

Buffet is looking at getting a possible 6 or 8 or 10% or 15% on that 345 billion or if there is a crash picking up some good cheap companies. He looks long term. He’s like a wild animal waiting patiently for that next meal to stroll by.

The Federal Reserve discusses slowing quantitative tightening (QT) in the “Participants’ Views on Current Conditions and the Economic Outlook” section (page 16 of the document January 28–29, 2025 ). Specifically, participants noted:

“Regarding the potential for significant swings in reserves over coming months related to debt ceiling dynamics, various participants noted that it may be appropriate to consider pausing or slowing balance sheet runoff until the resolution of this event.”

This indicates that the Fed is considering slowing the pace of balance sheet reduction (QT) to manage reserves amid debt ceiling uncertainties.

I discussed the reasons here further up in the thread, on Feb 22. So I’ll just repeat it here:

https://wolfstreet.com/2025/02/22/treasury-yield-curve-flattens-as-10-year-yield-falls-while-short-term-yields-stay-put-feds-pivot-to-wait-and-see-in-inflationary-times-but-mortgage-rates-stay-near-7/#comment-627023

Withdrawing liquidity is risky and can be messy. No one has ever withdrawn that much liquidity. So there is no playbook. There is now close to $800 billion in the government’s checking account (TGA) at the Fed that is going to get drawn down during the debt ceiling, to maybe near nothing, and that’s not a problem. The problem the Fed pointed at is when the TGA is down all the way, and the debt ceiling gets lifted, then the government has to go on a borrowing binge to refill the TGA. SO cash leaves the banking system to buy T-bills from the government, and reserves (cash that banks put on deposit at the Fed) might drop sharply. So at that refilling stage is when liquidity shifts from reserves (draws them down quickly) via government sales of T-bills to the TGA. It’s the refilling stage after the debt ceiling gets lifted – that potentially sudden and massive drawdown of reserves – that the Fed is worried about. At the end of the last debt ceiling fight, ON RRPs were suddenly drawn down because of the shift (cash shifted from money market funds to the TGA), and that was fine, but now ON RRPs are nearly gone, and so the refilling of the TGA might come out of reserves in an unpredictable manner. That’s what the Fed is worried about.

For example, if reserves plunge by $500 billion in a month, that’s a lot. That’s on top of the drawdown from QT. I don’t know if that would cause a problem, but I can see that they’re worried it might cause a problem. The way to continue QT for as long as possible is to avoid causing a problem – that’s what the Fed speakers said multiple times over the past 12 months, including Logan, and I agree with that. If something blows up, QT ends, and that would be too bad. So I’m on board with trying to avoid a blowup in order to continue QT for as long as possible.

Wolf thank you for teaching, or trying to, about how our systems work.

I struggle with it, so I’m saving this thread.

I got a call from Merrill during the start of the Great Recession, warning of a liquidity “problem” such that ATM’s might not be able to (temporarily) fulfill requests.

Could this happen now in the worst-case scenario as you describe?

I went to one ATM and it was out of order. But the other one worked fine. Large amounts of money are not being moved with paper-dollars today. Nor were they in 2008. It was done with a click, and now is done wither with a click or a tap.

Your call from Merrill sounds funny. They have a gazillion customers, with lots of money in their brokerage accounts; why would they call them all about a $400 ATM withdrawal?

Wolf, I keep getting “duplicate comment” messages when they are not duplicate.

Is there a “bug”?