Quantitative Tightening has shed 45% of Pandemic-QE. Bank liquidity facilities at or near zero.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

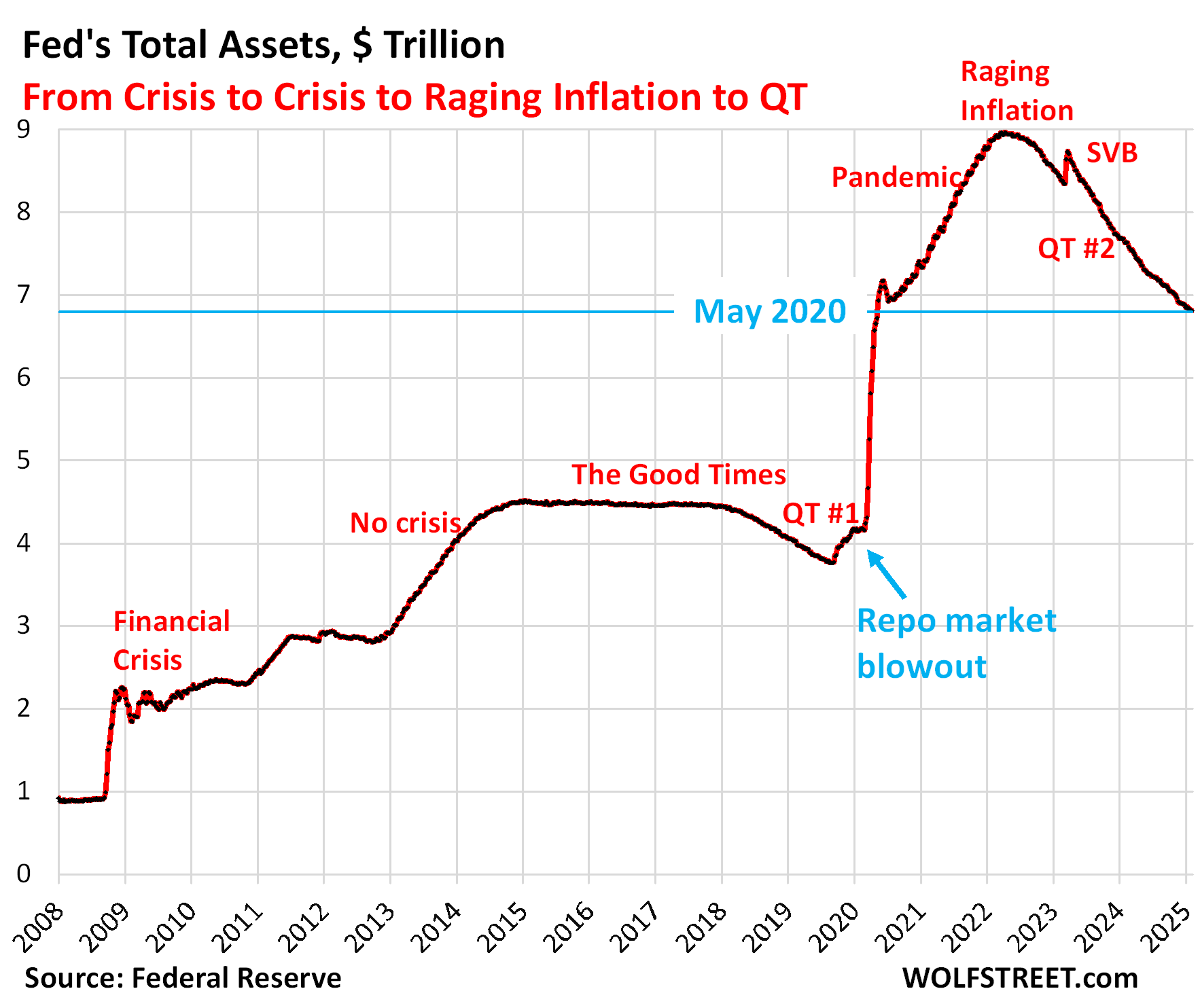

Total assets on the Fed’s balance sheet declined by $42 billion in January, to $6.81 trillion, the lowest since May 2020, according to the Fed’s weekly balance sheet today.

During May 2020, the third month of its mega-QE, the Fed had added $510 billion in that month alone to its balance sheet. So at the current pace of QT, we’re going to be saying “the lowest since May 2020” for about another 4-5 months. By the time we can say, “the lowest since April 2020,” the balance sheet will have dropped below $6.66 trillion.

Since the end of QE in April 2022, the Fed has shed $2.15 trillion, or 24% of its assets. Of the $4.81 trillion heaped on the balance sheet during pandemic QE from March 2020 through April 2022, the Fed has now shed 45%.

QT assets by category.

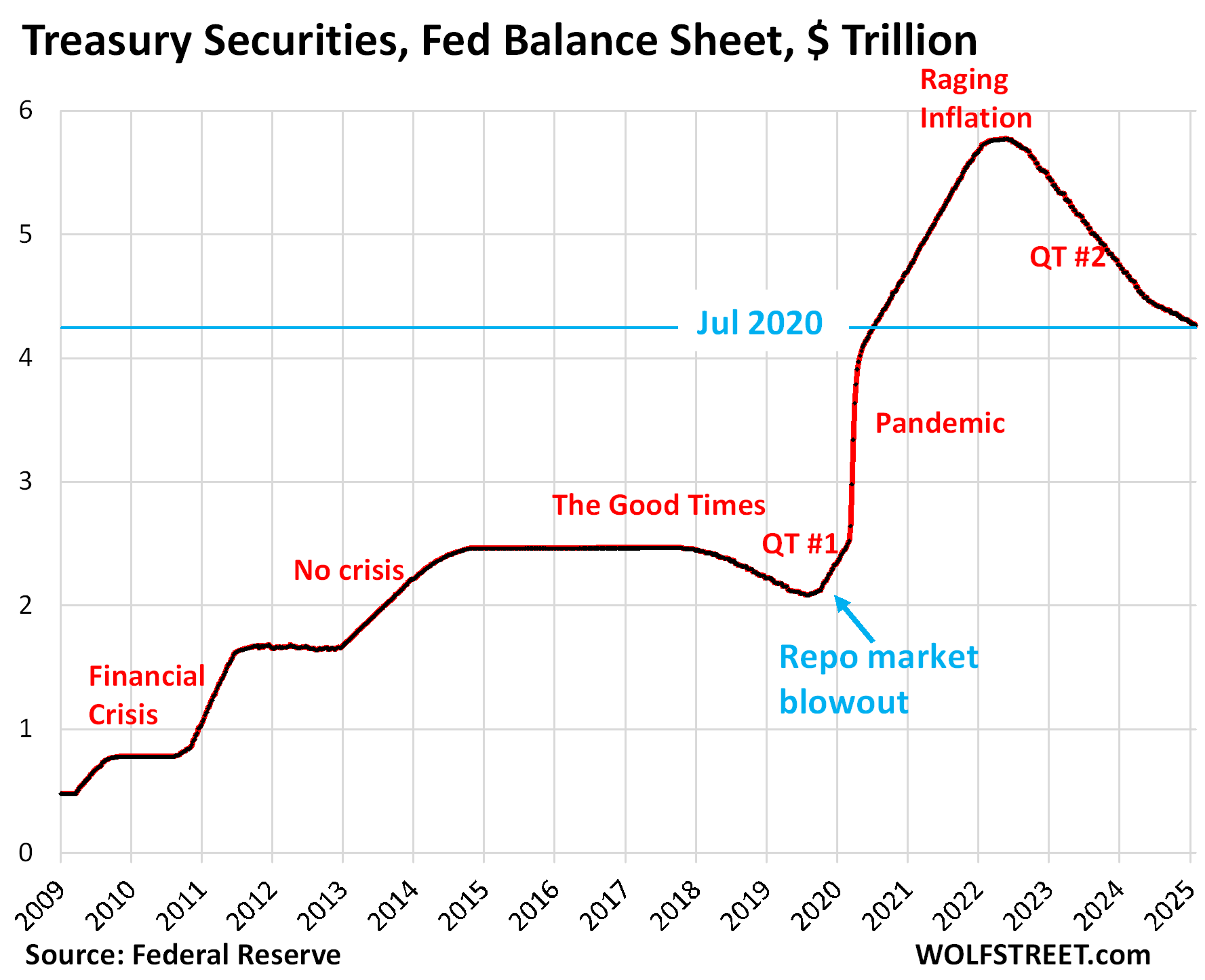

Treasury securities: -$25.2 billion in January, -$1.51 trillion from peak in June 2022, or -26% since the peak, to $4.27 trillion, the lowest since July 2020.

The Fed has now shed 46% of the $3.27 trillion in Treasuries heaped on the balance sheet during pandemic QE.

Treasury notes (2- to 10-year) and Treasury bonds (20- & 30-year) “roll off” the balance sheet mid-month and at the end of the month when they mature and the Fed gets paid face value. Since June, the roll-off has been capped at $25 billion per month. About that much has been rolling off, minus the amount of inflation protection the Fed earns on its Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) that is added to the principal of the TIPS.

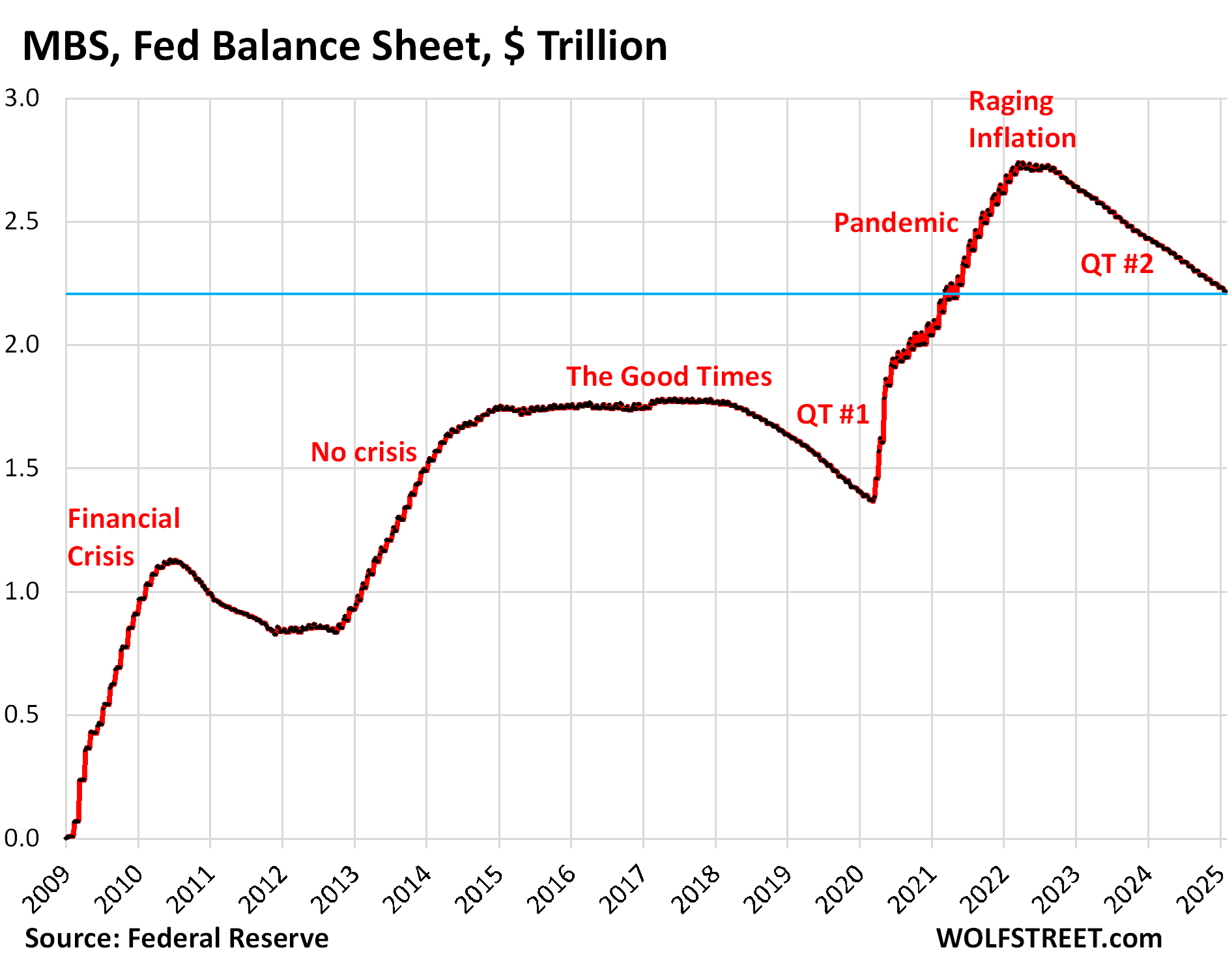

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): -$15.7 billion in January, -$522 billion from the peak, to $2.23 trillion, the lowest since May 2021.

The Fed has shed 19.1% of its MBS since the peak in April 2022. In terms of the MBS that the Fed had added during Pandemic-QE, it has shed 38%.

MBS come off the balance sheet primarily via pass-through principal payments that holders receive when mortgages are paid off (mortgaged homes are sold, mortgages are refinanced) and when mortgage payments are made. But sales of existing homes in 2024 have plunged to the lowest since 1995 and mortgage refinancing has collapsed, and therefore far fewer mortgages got paid off, and passthrough principal payments to MBS holders, such as the Fed, have become a trickle. As a result, MBS have come off the Fed’s balance sheet at a pace that has been mostly in the range of $15-17 billion a month.

The Fed only holds “agency” MBS that are guaranteed by the government and is therefore not exposed to losses if borrowers default on mortgages; the taxpayer would pick up those losses, not the Fed.

Bank liquidity facilities.

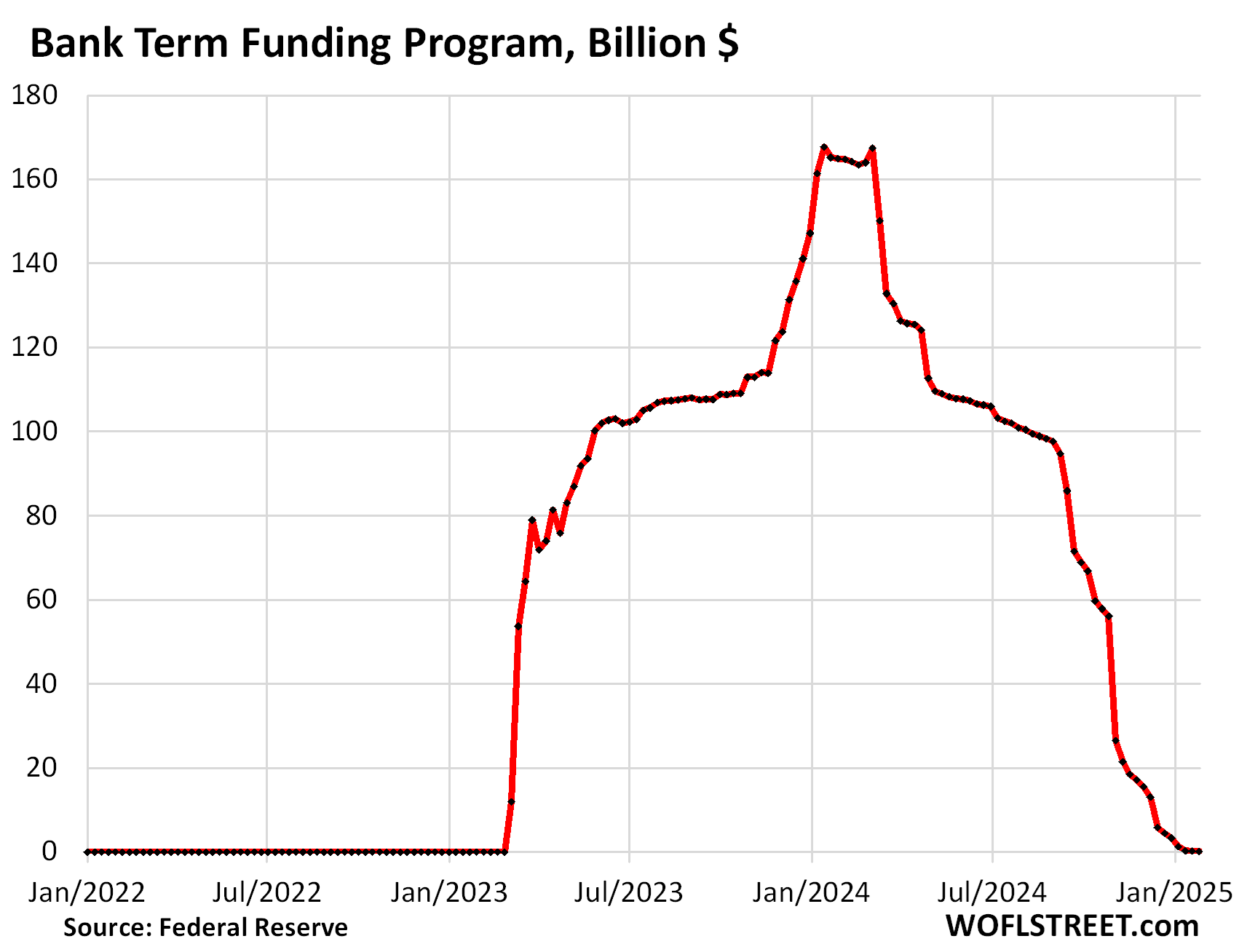

The Fed has five bank liquidity facilities. Four have either no balance at all or a balance that is essentially zero on the Fed scale, though they were heavily used after the SVB collapse. The latest addition to that essentially-zero list is the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP):

- Central Bank Liquidity Swaps ($76 million)

- Repos ($0)

- Loans to the FDIC ($0).

- BTFP ($197 million).

Bye-Bye BTFP: -$4.2 billion in January, to $197 million, down from $168 billion.

The BTFP was conceived in March 2023 after SVB had failed. But it had a fatal flaw: Its rate was based on a market rate. When Rate-Cut Mania kicked off in November 2023, market rates plunged even as the Fed’s policy rates were unchanged, including the 5.4% the Fed paid banks on reserves. Some banks then used the BTFP for arbitrage profits, borrowing at the BTFP at a lower market rate and leaving the cash in their reserve account at the Fed to earn 5.4%. This arbitrage caused the BTFP balances to spike to $168 billion.

The Fed, infuriated, shut down the arbitrage in January 2024 by changing the rate and decided to let the BTFP expire on March 11, 2024, and no new loans could be taken out since then. Nearly all remaining loans, which had a maximum term of one year, have now been paid off.

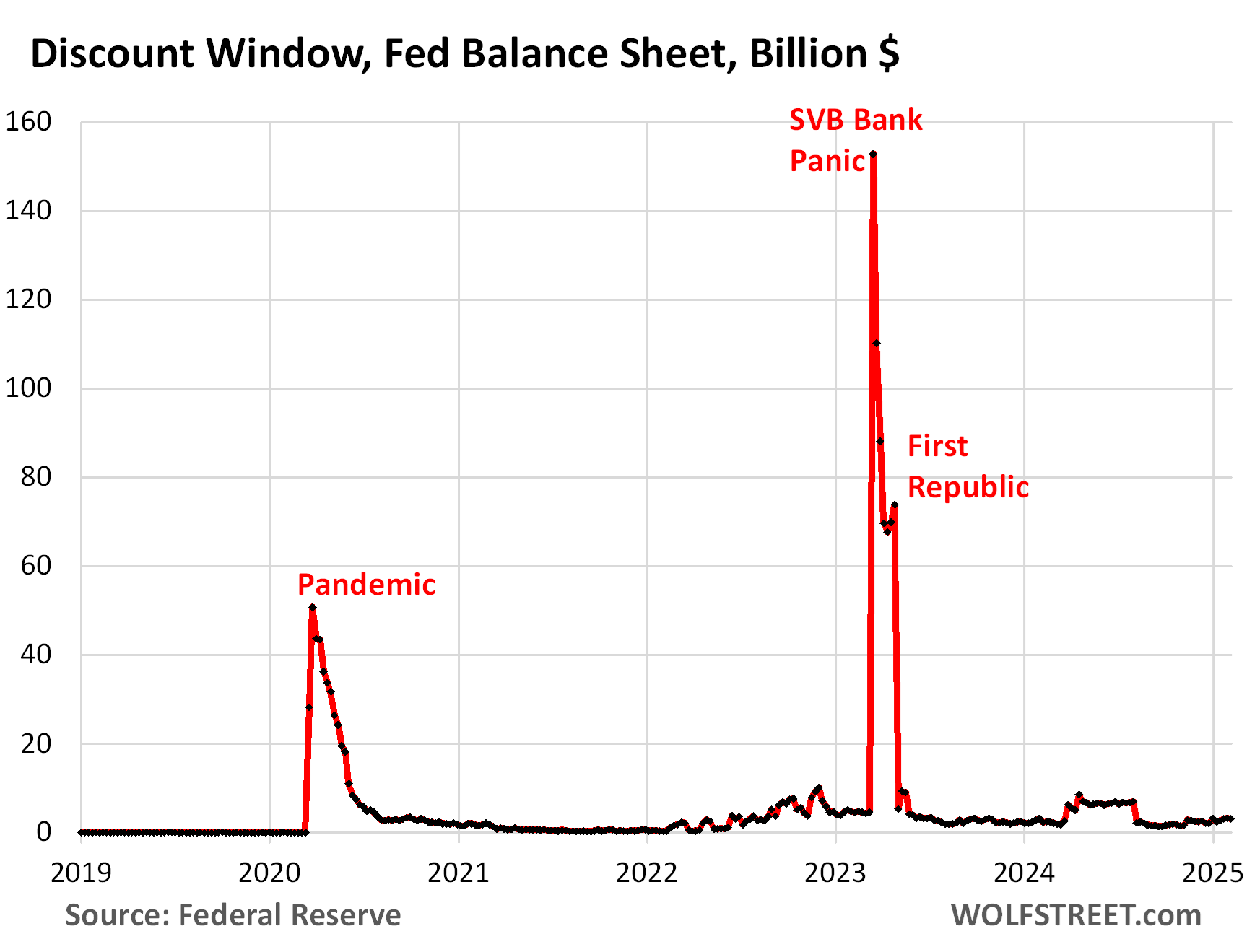

Discount Window: -$132 million in January, to $3.1 billion. During the bank panic in March 2023, loans had spiked to $153 billion. Even this balance qualifies as “near zero” as the chart below shows.

The Discount Window is the Fed’s classic liquidity supply to banks. As of the rate cut in December, the Fed charges banks 4.5% in interest on these loans and demands collateral at market value, which is expensive money for banks.

Powell has been publicly exhorting banks to use this facility more often, and practice using it with small-value exercise transactions, and to even get set up to use it, which many banks apparently are not, and to pre-position collateral so that they can use it when they need to. But there is stigma attached to borrowing from the Discount Window, and banks are reluctant to do it.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

IIRC, in a previous article circa last year, you mentioned that you didn’t think the Fed would be able to reduce their balance sheet below around $5 trillion without something “blowing up.”

How far do you think the Fed cam go?

The 4.? Trillion government securities can continue to roll off, with the Fed receiving face value to zero. Why not?

Michael,

That’s not what I said. I didn’t say “without blowing up.” It has nothing to do with blowing up. It has to do with liabilities, such as reserves and ON RRPs.

Here is what I said – it’s a long complicated article, but below is a snipped that gives you a feel, and note that it applies if the Fed wants to stay within its “ample reserves” regime. But the Fed doesn’t have to stay within it. It now has the tools to leave it, which is what the current article said the Fed is able to do, if it chooses to do so. Or it could run below ample reserves and still be OK.

https://wolfstreet.com/2024/03/23/the-feds-liabilities-how-far-can-qt-go-whats-the-lowest-possible-level-of-the-balance-sheet-without-blowing-stuff-up/

The “lowest possible level” of the Fed’s balance sheet in 2026?

No one knows, not even Fed, but here is our guess: $5.8 trillion, limited by the liabilities.

The minimum balance sheet level is determined by the liabilities. In the current setup at the Fed of “ample reserves,” it’s the reserve balances that the Fed will watch. If reserve balances drop too low, as they did in 2019, bad things can happen. Let’s say this theoretically lowest possible level of ample reserves is $2 trillion in two years. Add a little margin of safety, so maybe $2.2 trillion.

In this scenario, this lowest possible level of the balance sheet in this scenario would be $5.8 trillion, below which the balance sheet cannot decline without something blowing up:

$2.2 trillion reserves

$0 ON RRPs

$2.38 trillion currency in circulation, tends to grow over the years.

$900 billion TGA

$350 billion foreign official RRPs.

Realistically speaking, getting the balance sheet close to $6 trillion by the end of 2026, so shedding another $1.5 trillion, after the $1.45 trillion that have already been shed, will be a big improvement, meaning that the Fed’s balance sheet will by then have shed about $3 trillion, assuming that nothing blows up along the way.

Wolf,

The number the feels the most squishy in that calculation of reserves, which also happens to be the largest part of the total. I believe that is extrapolated from the repo blow up in 2019 (in another comment I mistakenly said taper tantrum) with a bit of economic growth thrown on top. However through the 80s, 90s and most of the 00s the economy grew and reserves seemed to fluctuate between a mere $10B-$30B with no ill effects With the SRF back in place, it seems unlikely that repos will blow-up again and, as fanciful as it sounds I see little reason they shouldn’t be able to get back to $100B. However, given the current rate of QT I don’t have a lot of faith the Fed has the patience (and political willpower) to keep something perceived as “restrictive” for that long.

Wolf-

Bernanke “scuttled” scarce reserve regime in 2008. Yet the scarce reserve regime system (with Secured Repo Facility) worked pretty well, as I believe you’ve said before.

What is the talk or likelihood of either:

A. reverting to the former regime of “scarce reserves?”

– or

B. experimenting with an entirely new regime?

The Fed is very incremental about the balance sheet, one baby step at a time with plenty of time in between. Right now the talk is about keeping QT going with in the ample reserves regime, and eventually replacing longer-term Treasuries and MBS with T-bills, and selling MBS outright. There is also talk of an after-QT situation where they’re keeping the balance sheet flat, rather than letting it grow with currency in circulation (paper dollars, a liability), which will have the effect of bringing reserves (a liability) down further, as currency in circulation grows based on demand, which would be a gentle form of QT (= reserves dropping) as it withdraws liquidity. I have not seen any talk of your #A and #B. All this is spread out over years.

Actually for Wolf:

This is just another example of why WE the PEONs want to get rid of the ”Fed” AKA Federal Reserve Bank:

Just another example of the manipulations TO SAVE and PROTECT the banksters at the expense of the earners and savers.

Say what you will Wolf, and I at least hope you know how much I revere your GREAT reporting,,, the FED is very clearly in business ONLY to protect the banksters and other equally rapacious parts of the oligarchy!

The alternatives are many, and it’s about time to tip the scales in favor of the workers and especially the savers instead of the banksters and the oligarchy in general.

Without doing so, IMO, after studying Constitutional Law for years, and, as you know, your wonderful reporting on the challenges WE face,,,, USA is going to go down the same path as did Rome, and all the other such oligarchies since.

VintageVNvet

If the Fed doesn’t support the banks when they keel over, the “savers” money is gone, dude. Which is what happened during the Great Depression. Not only savers’ money, but also payroll accounts, business checking accounts, etc., when a bank failed, it was adios money-in-the-bank.

VVnVet,

I generally appreciate your comments, but have to disagree here:

The Fed SHOULD be backstopping banks – being the lender of last resort is the proper function of a central bank. As pointed out in the previous article, the SRF was a staple of the pre-QE/Bernanke era.

On the other hand, it’s not the Fed’s job to be a market-maker for the Treasury market. And with QT they are stepping back from this role, which will help savers by allowing natural market forces to pull up fixed-income yields.

“The Fed is very incremental about the balance sheet, one baby step at a time with plenty of time in between. ”

Really, IN WHAT DIRECTION?

Looking at your first chart I see the balance sheet exploding higher on TWO occasions.

LMFAO!!!!!

> I didn’t say “without blowing up.”

> /the-feds-liabilities-how-far-can-qt-go-whats-the-lowest-possible-level-of-the-balance-sheet-without-blowing-stuff-up/

OK, but you gotta read the article.

love it – Powell hates Trump

and instead of ZIRP we’ll get real world rates

sometimes things work out

Just as I was about to accuse you of neglecting updating us on the FED balance sheet…you’re safe from the internet critics – for now!!

BTFP at $197M is just chump change now. They should just get it all off the books immediately. Therefore, I propose a win-win-win solution. Write it off and send me the notes that are due on. I’ll cut the banks a deal to pay me at 50 cents per. It’ll be a national victory. I’ll even toss in some hot dogs (chicken/pork only) for the celebration. (It might be $98.5M but I’m still staying on the cheap regardless.)

The loans have a term of 1 year and they stopped making new loans in March 24. Give it a month and it will all be gone.

Lune,

The BTFP ended on March 11 2024 officially per announcement. But in reality, they must have stopped making loans in January 2024 because they’re all gone, and that $197 million may just be unpaid interest due.

Overall I think the Fed is doing a good job now. I just wish they were more aggressive in the early months of QT. I understand that now that most QT will come from bank reserves you have to go slower. But money in the overnight repos is much more liquid and they could have easily doubled the rate of QT for the first year and drained the ONRRP account much faster. Then they could have slowed down and give more time for reserves to adjust.

Even now, the Fed should gently nudge the banks to start reducing their excess reserves by slightly cutting the interest paid on reserves. Most of that excess money will flow into treasuries and other assets, allowing the Fed to tighten faster. Pushing banks to do so ahead of QT forcing their hand would prevent last minute surprises.

The 6.66 Trillion number caught my eye, since the Philadelphia Eagles are sitting on 666 wins and 665 losses lifetime going into Sundays game…perfectly scripted like any major event, shock over the past 25 years…

“Inflation is transitory” is what got us into this mess

If I read correctly, it’s still a bit disheartening to see that $2.2 trillion of an $11 trillion MBS market is government owned, so does this mean one of every 5 homes in America is owned by the Fed?

The underlying mortgages are actually held by the government entities, which then created these MBS backed by them and they sold the MBS, but retained the mortgages. The Fed doesn’t own any mortgages or houses. It owns securities. If the homeowner defaults, the government can foreclose on the house and sell it to pay off the mortgage and maybe sue the homeowner for a deficiency judgement in a recourse state. Whatever happens, the government guaranteed the mortgages, and if there is a default, the government will buy back the MBS from the Fed at face value. So the Fed will get the cash, and the government will get the house.

What a disgusting, bloated mess.

I agree. We have now a hyper complex financial system with too many moving parts: Federal balance sheet, interest rates, fiscal deficits, trade deficits, stock market, derivatives, tariffs and more.

Is it any wonder that more and more people are finding some level of assurance/insurance in gold? I know I do. And while I learn alot from Wolf’s expertise, it only reinforces to me how utterly complex this all is.

Mike-

You said: “We have now a hyper complex financial system…”

Caused me to remember this quote from 9 decades ago:

“Of all the discoveries and inventions by which we live and die this totally improbable helix of credit is the most cunning, the most liable, the least comprehended and, next to high explosives, the most dangerous.”

—Garet Garrett, The Bubble that Broke the World, 1932

I’m not saying the system is not complex, but I’m not convinced the financial system is more complex now than 100 years ago.

It’s noteworthy, though, that the 1932 dollar has lost over 98% of its purchasing power, in terms of gold at today’s prices. Maligned as it is, the classic gold standard provided a relatively stable currency through the later half of the 19th century.

Our current central bank loses on that score…

” the 1932 dollar has lost over 98% of its purchasing power, in terms of gold ”

That’s a goofball comparison.

Gold is an asset. The “dollar” is a measurement, similar to “mile” or “pound,” that is used to measure something, such as incomes or asset values.

So compare gold to dollar-denominated assets, such as stocks, bonds, real estate etc., including the yield they pay, and then you have an intelligent comparison.

Yes, BY DESIGN. It great for facilitating FRAUD and making it impossible to actually prosecute. Don’t believe me? Perhaps I can interest you a some new financial “products”…

What’s wrong with the tariffs? [being sardonic] The drug cartels were never going to meet and say “Oh gee…. tariffs! We better stop smuggling….”

The result of the agreement with Mexico is 10,000 Mexican national guardsmen at the southern border. All that happens is the cartels’ payrolls increased by 10,000 and the 10,000 Mexican guardsmen are ecstatic over a raise….

I too agree with you DC:

As per my reply to Wolf above, this just another example of the FRB supporting the banksters and oligarchy at the expense of the worker/savers.

That was the reason for the establishment of the fed in the first place, and continues as the MAIN reason for ALL of their incredible and incredibly bad for worker/savers since…

We have an “elastic” currency “aided and abetted” by “elastic” legislators. We have perennial Walter Wriston caricatures pressuring the House Committee on Financial Services & the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs.

We have a conspiratorial organization that goes by the name of the American Bankers Association – with its well funded lobbyists that “routinely spends more money influencing legislation, than all other industry and labor groupings.”

VintageVNvet

If the Fed doesn’t support the banks when they keel over, the “savers” money is gone, dude. Which is what happened during the Great Depression. Not only savers’ money, but also payroll accounts, business checking accounts, etc., when a bank failed, it was adios money-in-the-bank.

I thought with QT and high interest rates there was no way the market could keep climbing up, it turns out that is not the case!

Google, Microsoft and now Amazon are pot committed in this poker game. They already have blown insane money down this NVDA rabbit hole, and either admit they should lose their jobs, or continue to destroy capital and temporarily preserve their market cap. They chose the later.

The genie is out of the bottle. Deep Seek just handed out the source code so anyone can fine tune or modify their work delivering A.I for pennies on the dollar. Next comes Alibaba claiming their A.I, offering outperforms Chat GPT-4o, Deep Seek-V3, and Liama-3.1-405B.

The Chinese are winning this war. BYD is the world’s largest EV maker. They dominate batteries, solar panels and drones. Even Huawei turned sanctions against them to become a leading chip maker.

The idea that we need dedicated nuclear power plants to power NVDA chips to try to create something that would never replace a Wolf Richter is ridiculous.

Wiley E. Coyote didn’t just step off a cliff, he is holding an anvil.

it’s funny. i noticed several months ago that the whole ai thing seemed to be the other bigtech players buying nvda chips to try to one up each other.

i didn’t see any evidence anyone was actually making money on it.

That’s why the crystal ball is so clear. The emperor is stark naked.

Sam Altman is the poster child for greed. Ironically “Open A.I.” (which is what China is actually handing out) is destroying ALL of the capital foolishly squandered into NVDA chips. Elon Musk co-founded Open-AI in 2015 and offered a rescue at 97.4 Billion (Sam wants $300B) which will soon be worthless.

No one has made a dime on this entire charade.

Business schools will be teaching tulip bulb mania was surpassed by the NVDA chips mania.

Even Isaac Newton lost his fortune in the South Seas bubble.

Intelligence is a disadvantage if you are looking for a consensus, because at market extremes you have to recognize that everyone has already been bamboozled by running to the same crowded side of the ship. And we, the winners, calmly walk over to the empty other side of the ship. NVD is 2X short.

I tend to think that physical production in America is necessary, duh, to reduce the trade deficit of 8 or so percent of the national budget.

The kernel of the national budget deficit which Trump’s tax reduction on people that pay a lot of taxes instigated is now his problem.

Me too. Of course I have been a bear in an era, when Bulls ruled the roost.

I just don’t understand the valuations.

The Fed needs to keep going, dump ALL the MBS Jerome. The Fed never should have bought MBS, as this just rewarded FRAUD.

1971 was an inflection point in TRUST, so was 2007/2008. Monetary systems come and go, but are always built on trust.

Interesting times Wolf.

I think the Fed is accomplishing a financial structure that allows the markets time to equillibrate during the transition from the monetarist experiment to a more historically based experience.

Zero interest rate policy. Never attempted during the 6000 years of previous history.

The Euro is a currency destined too fail. They adopted it first and went so far as offering negative interest rates on one’s life long savings,

All the while, the roar of the asset market bull, ignored the seed corn. The asset markets are seriously over priced. A better time to sell than buy.

“Treasury securities: -$25.2 billion in January”

Is the $25B per month not a hard limit? They can let the rolloff go a little over?

Close enough is good enough. They say as much in their Implementation Notes. What also happens is that the inflation protection amount on TIPS is added to the principal of TIPS and so the TIPS principal, including inflation protection, keeps growing until they mature (just like it would in your portfolio). So in most months, that added inflation protection reduces the roll-off to something like $24.5 billion.

Close enough for government work!

Oh yeah, silly me, I was taught that interest rate was a summation of the risk. IMO the most undervalued asset is risk aversion.

The first risk is the probability of business loss accrued to an investor. Let’s say 3 pct

The second risk is inflation which is currently is running at 3.1 pct say, that puts the FFR at 6.1 pct.

Like I said, the valuations dont make sense too me.

Looking forward to the next article on housing inventory. For sale new homes in my market are ballooning, as are existing homes for sale, as are homes (new and existing) that are up for rent. It reminds me of the scene from The Big Short: “is there a real estate bubble or isn’t there, and if there is, how exposed are the banks?” I wish I knew how many people have borrowed against the “equity” in their house – equity that may be illusory. In Naples, FL, it almost feels like more homes are on the market than not. This is all tied into the Fed’s ability to loosen policy in the face of inflation and current chaos in the Federal Administration.

The Kalifornia Karens are doing a very good job in keeping our West Hawaii market trending ever higher. They have a seeming insatiable appetite to overpay for homes. Still seeing many sales double what the seller paid just 2 years ago. Of course, this is not in the low end. It is in the $2m+ range up into the $20m range. I can only assume that if the strategy worked for their NVDA then why not in homes and condos as well?

Active listings in Toronto Regional RE are 17000, up 70% over this time 2024.

I remember the “using your house as an ATM” days.

Todays higher rates take the fun out of that.

My guess is yes and no. Yes we as a nation are living through a period of reflection

A couple of days ago I mentioned that another GI had passed away well then I began to continue with my life when it occurred to me the changes he navigated, born on the cusp of the 1919 armistice. The roaring twenties, the great depression, four years in the WW2 European theater, all before he was 30.

Then the Korean War, Vietnam, 50 years ago, before the advent of the digital computer

etc

I really wish they would have let it play out in March of 2023 instead of concocting another ill conceived bailout facility because some billionaires cried on Twitter. The banks that were poorly positioned for higher rates should have failed. Their depositors should have been cleaned out. The markets should have fallen. And maybe some of the poors could have emerged from the rubble and gotten their hands on some assets for once.

“Their depositors should have been cleaned out.”

Should be “uninsured depositors.”

In fact, even they wouldn’t have gotten “cleaned out.” There were enough assets at these banks to cover most of the deposits. Hedge funds, calculating this, were already offering cash advances on those deposits of 70-80% of the deposit value before the FDIC/Fed decided to bail out all depositors in full. Without bailout, they might have gotten a haircut of 10% or 15%. That’s how it should have been. But at least they let the banks fail, shareholders got wiped out, and bond holders got wiped out, and management got fired and some got sued – instead of being handed bonuses as in 2009.

What is the Peoples Bank of China balance sheet at for comparison? What are the total outstanding balances of all central banks combined globally by “assets”….

Yes, their panic in the face of the banking nanocrisis is easily the second most infuriating thing the Fed ever did.

Things had been going remarkably well since June 2022–the stock market bubbles were deflating, crypto was rapidly being repriced to its intrinsic value of near zero, and housing prices were *actually going down*. All of it in a nice controlled fashion.

And then a couple of systemically unimportant banks teetered and the Fed shat their pants. It wasn’t just the bailout of uninsured Silicon Valley freaks, it was the combination of that with the pause in rate hikes that showed the markets that it was bubble time again. The Fed wouldn’t dare to try to contain them.

and that’s ultimately why stocks are where they are today. everyone is convinced the fed won’t tolerate more than a 10%-15% drop or so. enough people believe it, and it creates a positive feedback loop for a while.

Pea See – agree with the general vibe of your comment, but have to nitpick one thing: the Fed didn’t pause rate hikes because of SVB, they kept hiking thru that summer.

Agency MBS is Freddie and Fannie, etc, these are somewhat subsidized loans, usually at discounted rates, to secure borrowers. Not subprime. The idea is out there that if the Fed were truly independent there would be no taxpayer funds posted as collateral. In a political environment of radial restructuring this is still possible. Once the Fed disgorges itself of treasury, what are the odds? and what is the likely outcome if the Fed is truly independent?

Is it just me, or did the BTFP f’up by the Fed, which allowed the banks to arbitrage for profit, essentially amount to allowing the banks to steal tax-payer funds?

Do we know how much the banks managed to siphon off in arbitrage profits?

It was their way of recapitalizing the banks

LOL, the activity was limited to small banks, in the $23-trillion banking system, as you can see in the relatively tiny amount of $60 billion being used for arbitrage. If they made an average spread of 0.5% over the course of the loans, it would have made them $300 million in profits. By comparison, one bank alone, JPM made an annual net profit at $49 billion in 2023. That $300 million in potential arbitrage profits wasn’t even a flyspeck in the huge US banking system. But some small banks did make some extra money and drew the ire of the Fed.

I know it’s en vouge to heap scorn on the FED and often for good reason, but I am glad they are continuing to tighten. I disagreed with the rate cut, but I understand why they did it. The only complaint I have is they haven’t raised the rate a quarter to half point.

Let’s hope they continue until we get back to at least pre pandemic levels.

Off topic but I have read and checked that room rates on the Las Vegas strip have collapsed for Super Bowl weekend. Mandalay $60, Caesars $89, etc. Weird. Usually a big weekend out there? According to google result:

“It’s Vegas, baby, so the Super Bowl, one week from tomorrow, is one of the most vibrant, action-packed, crowded (more than 300,000 visitors expected), and expensive weekends of the year, blending the excitement of one of the world’s biggest sporting events with the unique energy of Sin City.”

These bonds that are ‘rolling off’ the ‘Fed Balance Sheet’?? Aren’t these bonds on the balance sheet there because there were originally no buyers?

Now that they’re ‘rolling off’ and the ‘Fed is getting paid face value’, my question is who is paying them?

Sounds to me that the US government is bankrupt and has been for awhile.

I have a CPA background and it is hard for me to call the Feds BS (balance sheet) a balance sheet when all i see are Assets. Instead I see it as Fed’s BS.

1. There were plenty of buyers, but the Fed muscled in front of other buyers to push down the yield, and push up prices, which is what QE was all about. Were you totally asleep at that time?

2. Bonds “roll off” the Fed’s balance sheet when they mature, and US Treasury department pays ALL bond holders face value for maturing bonds, including the Fed. If you have Treasury securities in your brokerage account, you will see the same thing: you will get paid face value from the US Treasury when the securities mature. That’s what “mature” means in terms of bonds.

3. The government cannot go bankrupt, cannot even file for bankruptcy, because there is no court for it file for bankruptcy in, LOL.

4. Sounds to me like you don’t even know what a CPA is. If you passed the CPA exam, you would know what happens when bonds mature, LOL, and you would know that the government cannot go bankrupt, cannot even file for bankruptcy, because there is no court for it file for bankruptcy in, LOL. And if you want to look at the entire balance sheet of the Fed — assets, liabilities, and capital — you can. All you have to do is look it up:

Weekly balance sheet here: https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/20250206/

Quarterly reports here: https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/combined-quarterly-financial-reports-unaudited.htm

Audited annual reports here: https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/audited-annual-financial-statements.htm

How do you know how much the FED has on their books considering no one audits the FED’s books.

ignorant BS. The Fed’s books are audited every year by KPMG which also audits the books of the biggest companies in the US. Here is the latest audited annual report:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2023-annual-report.pdf

Post your BS somewhere else. Adios.