As a growing population financed more costly purchases, total debt rose. But income rose even faster in recent quarters.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

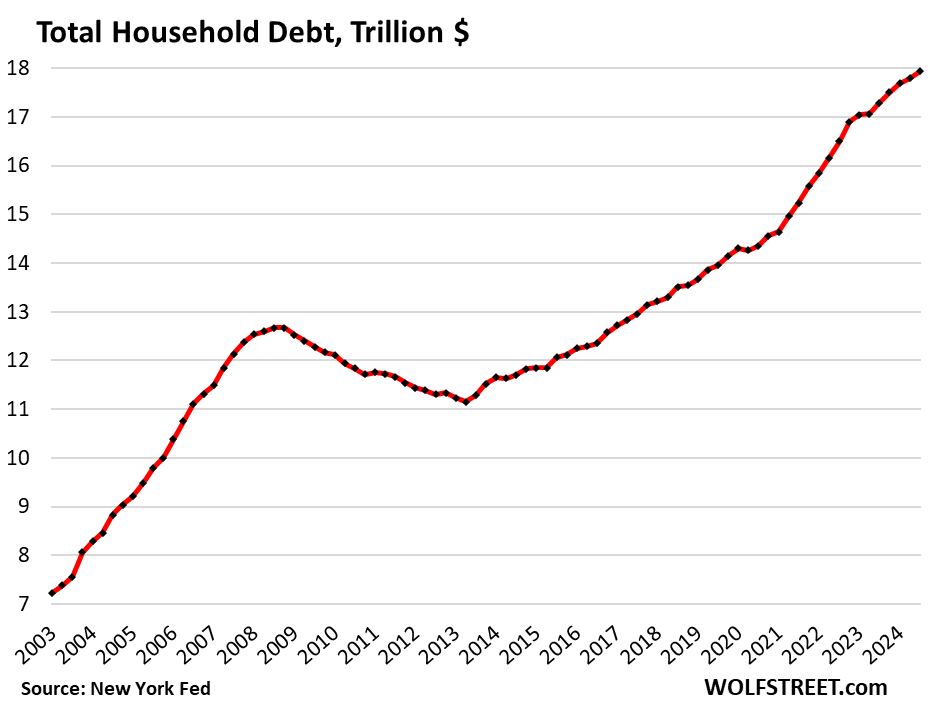

Total household debt outstanding ticked up by $147 billion in Q3, or by 0.8%, from Q2, to $17.9 trillion, according to the Household Debt and Credit Report from the New York Fed today. Year-over-year, total household debt grew by 3.8%. Debt grew due to a mix of several factors:

- More borrowing capacity: Wage increases and the larger number of workers produced substantially higher overall personal income, which increased borrowing capacity.

- Higher prices: Homes, vehicles, and other goods and services that people finance got more expensive over the years — Home prices have exploded by about 50% since 2020; and consumer price inflation, as measured by CPI has surged by 22% over the same period, and those who borrowed to purchase homes and other things had to finance much larger amounts, but they had more income to do so.

All categories – mortgages, HELOCs, auto loans, credit cards, other revolving credit, and student loans – increased quarter-to-quarter and year-over-year. We’ll get into the details of each category in a series of separate articles over the next few days. Today, we look at the overall situation, along with delinquencies, collections, foreclosures, and bankruptcies.

The relative burden of household debt.

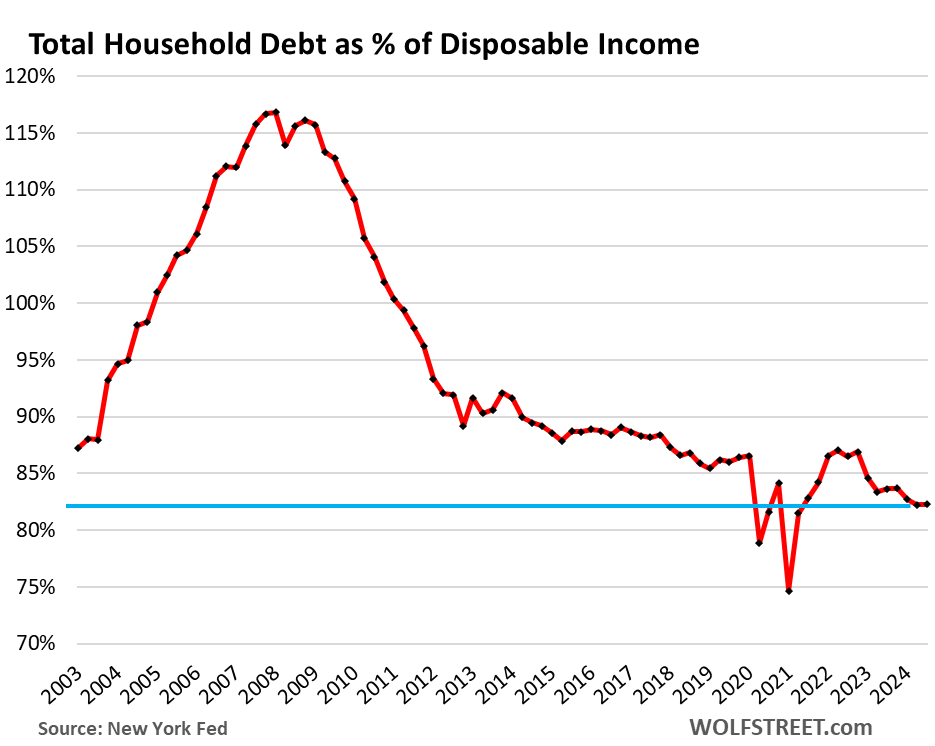

One of the ways to measure the overall burden of debt on households is to compare the debt levels to their income that is available to pay for debt service.

We use “disposable income” for that purpose. That’s income from all sources except capital gains; so income from after-tax wages, plus from interest, dividends, rentals, farm income, small business income, transfer payments from the government, etc. This is essentially the cash that consumers have available to spend on housing, food, cars, debt payments, etc. And what they don’t spend, they save.

Disposable income grew by 0.8% in Q3 from Q2, and by 5.5% year-over-year, according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. So quarter-over-quarter, disposable income rose at the same pace as total consumer debts, and the burden of the debt remained the same; while year-over-year, disposable income rose nearly 2 percentage points faster than debt, and year-over-year the burden declined.

The ratio of 82% in Q3 was historically low, bested by only a few quarters during the free-money-stimulus era that had briefly inflated disposable income beyond recognition.

So the aggregate balance sheet of consumers is in good shape – the heavily leveraged entities in the US are the federal government and businesses, not consumers.

But in the runup to the Financial Crisis, consumers were mightily overleveraged, with debt-to-disposable-income ratios exceeding 115%, and then the leverage blew a fuse. Our Drunken Sailors, as we’ve come to call them lovingly and facetiously, have learned a lesson and have become a sober bunch, most of them, not all.

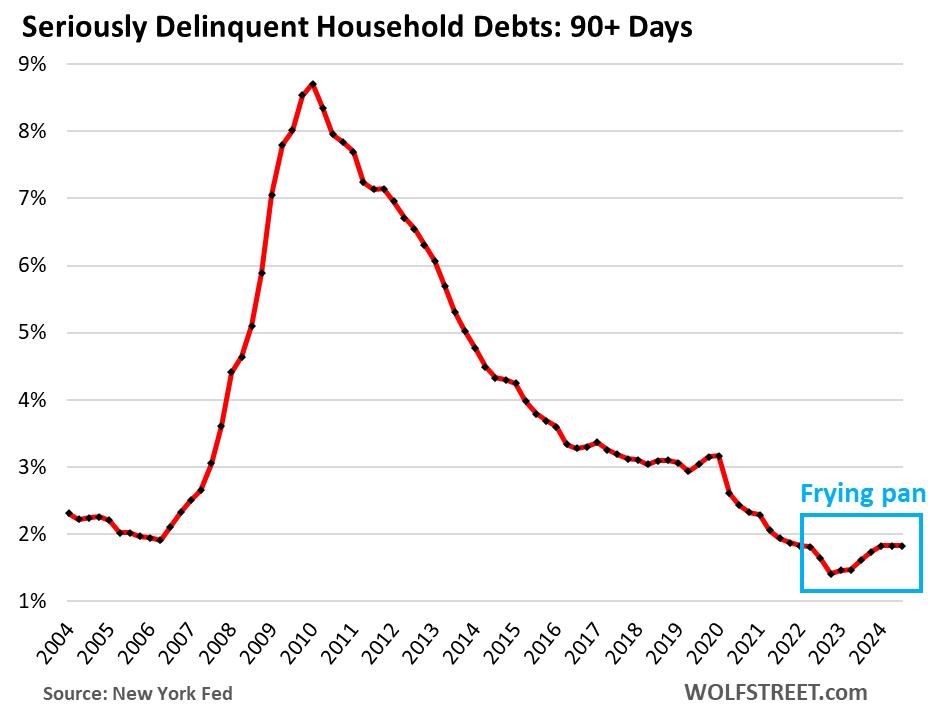

Serious delinquencies form a frying-pan pattern.

A small portion of our Drunken Sailors is always in trouble, they have subprime credit scores because they’ve been late with their payments, have defaulted on their obligations, etc. Subprime doesn’t mean “low income,” it means “bad credit,” and goes across the income spectrum. They’re a relatively small portion of consumers. And they’re always in flux: Some people get into trouble, and their credit scores drop to subprime, while others are working their way out of subprime as they cure their credit problems.

But the vast majority of our Drunken Sailors are keeping their credit in decent to excellent shape.

Household debts that were 90 days or more delinquent by the end of Q3 remained unchanged for the third month in a row, at a historically low 1.8% of total balances outstanding, lower than any time before the free-money-era of the pandemic.

The drop during the free-money era and then the climb back to what are still historically low levels forms what we’ve been calling a frying-pan pattern that is now cropping up a lot in the world of debt problems:

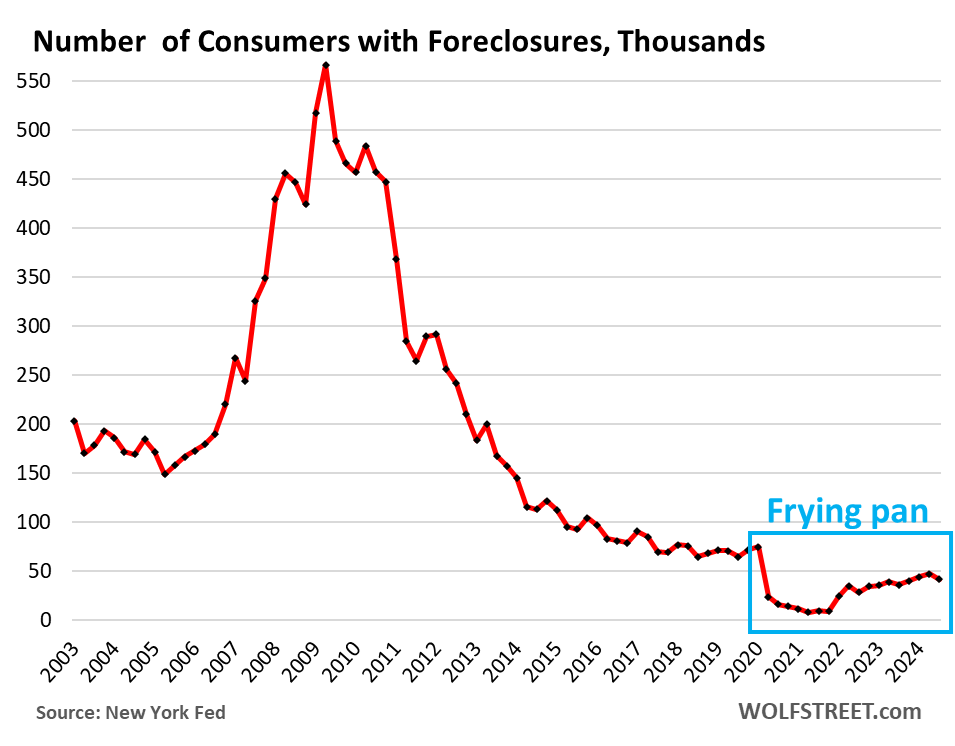

Foreclosures form frying-pan pattern.

There were 41,520 consumers with foreclosures in Q3, down from 47,180 in Q2, and compared to 65,000 to 90,000 in the years 2017 through 2019. Outside of the free-money and mortgage-forbearance era during the pandemic, which reduced the number of foreclosures to near zero, there was never a period in the data with fewer foreclosures.

And this frying-pan pattern makes sense: After three years of ballooning home prices, most homeowners, if they get in trouble, can sell their home for more than they owe on it, pay off the mortgage, and walk away with some cash, and their credit intact. It’s only when home prices spiral down for years, combined with high unemployment rates, that foreclosures become a problem.

Third-party collections not even in a frying-pan pattern.

A debt goes to a collection agency – the third party – after the lender has given up on the delinquent loan, has written it off, and has sold the account for cents on the dollar to a company that specializes in squeezing debtors until they cough up some money.

The percentage of consumers with third-party collections dipped to 4.60%, a new record low in the data:

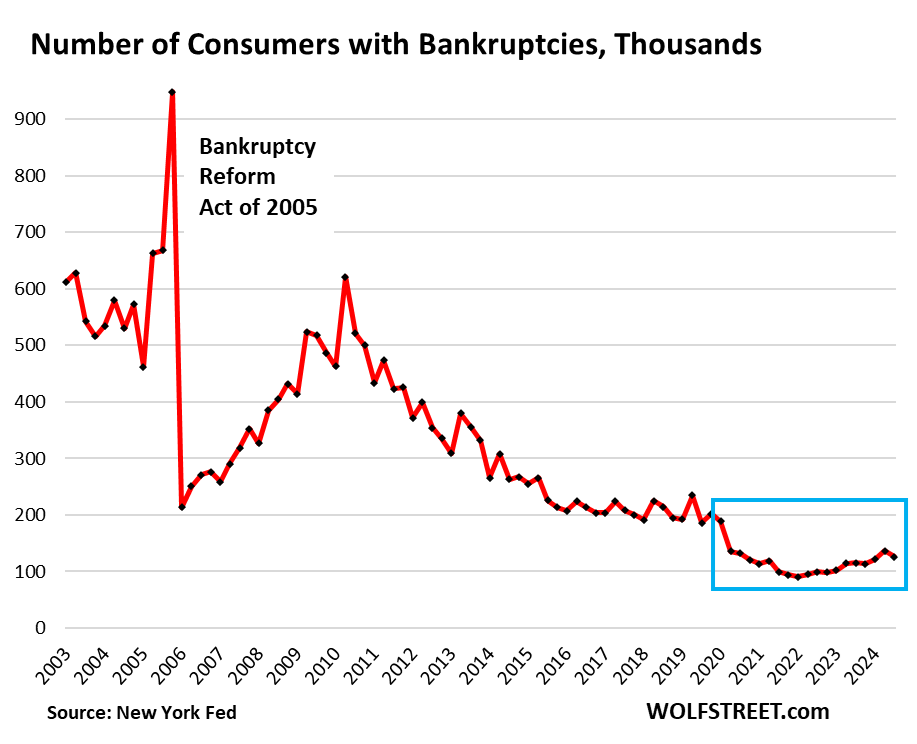

Consumers with bankruptcies form frying-pan pattern.

The number of consumers with bankruptcy filings dipped to 126,140 in Q3, lower than any time before the free-money era. In Q2, there were 136,180 consumers with bankruptcy filings. In 2017-2019, during the Good Times before the pandemic, the number of consumers with bankruptcy filings ranged from 186,000 to 234,000, which had been historically low.

And the frying-pan pattern crops up again, this one with a short and low burn-your-fingers handle.

We’re going to discuss the details of housing debt, credit card debt, and auto debt in separate articles over the next few days. So stay tuned.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Much is written about medical debt, and I am curious as to how much medical debt as a specific category such as student debt, housing, auto and credit card debt influences overall consumer health. It has been estimated that medical debt contributes to 40 to 60% of personal bankruptcies. An article from the KFF Health System Tracker offers useful information,

htps://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/the-burden-of-medical-debt-in-the-united-states/ .

The information presented is based in part on surveys circa 2021 and includes data from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFDB) which estimates that $88 billions in medical debt is reflected in credit reports, and Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). One estimate is that by the end of 2021 there was $220 billions of medical debt although the total could be masked by medical debt on credit cards or debt owed to family members.

The KFF report includes stratification of debt by amounts and patient ages. A large share of total medical debt is held by a small share of people. 6% of U.S. adults owed more than $1,000, 2% owed more than $5,000 and 1% owed more than $10,000. 0.3% of adults accounted for more than half of total medical debt. This reflects the cumulative expense of chronic disease. I would add that catastrophic illnesses such as cancer can bankrupt you.

It occurred to me that the young age of recent migrants might mitigate against higher individual medical use and hence debt although the KFF article includes data on obstetrical debt. Low skilled and hence low wage migrants in aggregate could result in increased costs to the health system as there are reports of stressed hospital systems in high migrant areas.

1. “I am curious as to how much medical debt as a specific category”

Much of the medical debt is INCLUDED in credit card debts and other revolving debts, such as personal loans, because that’s how people pay for it, and therefore is included in the data here.

2. “…has been estimated that medical debt contributes to 40 to 60% of personal bankruptcies.”

RTGDFA, I gave you the chart of personal bankruptcies. SO you can see how much of a problem that is, LOL. So here it is again:

Federal law says emergency room that day medical conditions are required to be billed at in network cost but all hospitals usually bill the out of network cost which is much higher

House prices increased by 50% but it wasn’t income that supported the home prices, it was artificially low interest rates. Now those people are stuck in the homes they bought. Many were first time home buyers promised by real estate agents that as their families grew they could get another home….. well…. Unless the Fed does another massive QE, I don’t see that happening.

I dunno, isn’t it more a market price set by uninformed, Zillowfied owners?

Aren’t they holding us hostage?

They’re greedy and want theirs. Their 💰

One concern I have is thst the income to debt ratio may be a little misleading since it’s not just the volume of debt but the cost of that debt. All debt that has been originated in the past 3 years is at least 50% more expensive than 2019 and that’s on top of everyday costs up at least 22%

Disposable income, the metric used here, is up 33% since 2019.

So real disposableincome up +/-11%. Household Debt up 28+% (vs 33%) plus that debt does not include BNPL since not a bank product so not in FRED numbers. Relatively small but growing burden.

So disposable income up 33%,everyday costs up 22% and the ever rising debt cost is up 50++% with shadow debt in the form of BNPL growing as well. HELOCs growing 10 consecutive qtrs on top of rising crefit card debt. Personal savibgs rate drops from 7.0% to 4.6%. Sept vs Sept) Confusing economy with headlines this week 30% people with student loans went without food or medicine;,68% of retirees now carrying credit card debt and yet retail sales look reasonable (though not adjusted for inflation flation)

The rise in home prices is often close to 50% as James mentioned.

But I guess most people’s wages have not gone up by 50% right now. So, is the expectation that we have to increase our wages by close to 50% over a short time (say 5 years) ? Hopefully, the home prices wont increase too much in those 5 years.

Most people can’t quick pay increases to afford such homes right NOW, unless they are a rockstar in such professions – software engineering, doctor, lawyer, finance or business. I guess wait for 5 years or so & hope that the crooks at the treasury & fed dont overstimulate the economy or print dollars.

That’s the story I hear from the 25-35 year old crowd at work on a regular basis. Basically outgrowing their starter homes and unable to move up financially. In a way I suppose they shoulder some of the burden of lowering inflation IF they continue to save for that bigger home and don’t go blow their raises on a new car or some other depreciating asset.

Great data presentation… thanks! I’m looking forward to the further discussion of household debt categories, detail and analysis.

It would be equally interesting to see how household debt fits into the larger total national debt picture: federal and state debt; corporate debt; household debt; financial services debt. I used to see charts tracking total debt to GDP, which figure had doubled over several decades, but don’t see those stats quoted much anymore.

Are rising total debt to GDP datapoints worthy of trend analysis?

So why is the Fed dropping rates?

Corporate and. Government debt?

Once again the fix is in at the Fed to bail out companies

The Fed dropped the rates because its measure of inflation was/is below 3% and its rates were at 5.5%, and now are at 4.75%, and because the labor market data went into a down-spiral over the summer. The down-spiral has been revised away. But short-term interest rates substantially above inflation rates is a good place to be.

What we had between 2008 and 2020 were inflation rates of 1% to 2.5% and interest rates mostly near 0%, with two years of higher rates of up to 2.5%, still only matching inflation at peak rate, not exceeding it. So that was bad. In 2021 through early 2022, we had lots of inflation shooting toward ultimately 9% and near-0% interest rates. That was really bad.

i guess i don’t see why a 2-3% delta between the fed funds rate and inflation rate is such a bad thing.

The Fed doesn’t want to be too restrictive because that would conflict with the employment side of their mandate.

A 2-3% delta between the fed funds rate and inflation rate is a great thing for us sober sailers with a positive net worth! If the newly elected drunks would just hint at a tad of fiscal discipline and even acknowledge a wee bit of concern over the inflationary policies that the working class was just convinced are appealing, long-term rates may stabilize and bonds wouldn’t be such a painful investment.

You have seen the government debt to GDP chart here many times.

In terms of “consumer debt to GDP,” it’s going to look similar in shape to “consumer debt to disposable income” above because GDP and disposable income grow roughly in parallel.

Here’s the government’s mess:

The government isn’t a diamond pooping unicorn that lives in splendid isolation on a clover covered hill…*its* debt burden is *our* debt burden since the only ways the G can service or repay its engorged debts are taxation or money printing in one form or another (ie, citizen inflation).

Given the multi-decade decline in true economic growth rates, I wouldn’t count on economic growth to continue to obscure the reality of the first paragraph.

McKinsey Global’s GFC post-mortem “Debt and Deleveraging” (2010) looked at the world’s most significant economies. They measured:

– Government Debt (Federal/State/Local)

– Non-financial Business Debt

– Household Debt

– Financial Institutions Debt

Tracking the total (p. 59 in the report) revealed this startling growth in “total” US borrowing as a percent of GDP:

1960 – 134% total US debt to GDP

1990 – 204%

2009 – 296%

It’s the growth trajectory, which I believe has continued over the subsequent 15 years, that I find alarming.

I’m struggling to reconcile this, rather positive, debt data, with the fact that so many people claim to be struggling.

Insurance and health care are still rising, food and autos seem to have leveled off (where I live) or come down a little.

The chart shows people are not borrowing more relative to their income to meet their needs. Disposable income is up.

I don’t understand.

Could it be the higher level of complaints/visibility for that population, in the age of social media? People not struggling are not appearing in that space, not attracting media attention as much. I guess in a statistics sense, how representative is that sampling?

phleep,

Yes, that’s definitely the case. And people might pick certain parts of it that fit into their narrative of most Americans “are struggling.” That’s what data is for, to dispel this BS.

Sure, there are people living in cardboard boxes, but that’s a minuscule percentage of the population. And there are people who are very poor, and that’s a small part of the population — see the data on median incomes below. But if you just watch YouTubers screaming about people living in cardboard boxes and abject poverty, and that’s all you see because that’s all you want to see because it fits into your narrative, you end up thinking that only 10% of Americans live in houses and 90% live in cardboard boxes and abject poverty, and that’s going to pollute your brain.

Old Engineer,

People are pissed off about higher prices. These prices piss me off, and we can afford them no problem. Americans are not used to seeing surging prices. We (me) are feeling like we’re getting ripped off on a daily basis. 2021-2023 was an inflation shock. Now inflation (a rate of change) is lower, but prices are still high, and incomes have risen especially at the lower end of the wage scales. But those high prices and new price increases really piss people off, and they’re in a foul mood. People HATE HATE HATE inflation and high prices, even if they can easily afford them. And so they complain about the economy.

Median household income in the US is $80,000. Meaning that HALF of the households make over $80k a year. And of the half that makes less than $80k a year, lots of them make $60k-plus a year.

And so people have money to spend, and they have relatively little debt, 65% of the households own their own home, 40% of them don’t even have a mortgage, and they’re spending a lot, and they’re STILL saving quite a bit. And they’re still pissed off about the high prices.

You just articulated something that has been bothering me for quite a while. I too can afford the new prices, but they make me angry.

It is the feeling of being ripped off that pisses me off!

I’m not paying $500 per night to stay in your ABB! Then my wife calls and negotiates it down to $250, which is where I thought it should be, and I’m happy.

Pricing from 4 years ago may never return. But our value expectation meters are sure stuck there.

Also not paying $80k for a new truck. But then again, what happens when I need one? (Yes I buy used for commenters)

Most people I know are comfortably fine, but not by a large margin.

I did get your response about moderation. Hope this email suffices.

Thanks for the mail change. Your next comment should fly through.

Inflation and market leveling is what has everyone on edge. We all hate higher prices, but the market has to find the right price and spends a portion of time doing so, being too high. This is felt most by those that felt they were “getting by”.

For those that were comfortable, they generally remain so, but have to change the plans they made for the expendable cash they previously had. That makes us frustrated, sad, and a little angry.

I shop all the sales and minimize spending.

Hell Clark Howard was the key note speaker at Bogleheads conference a few years ago. (I mean that’s saying something right there)

Everyone needs to be frugal, even if you’re rich.

Still you have to pay all the over priced bills as well.

Phleep/Wolf,

Thank you!! That is how it is.

And…some people have simply been told we are in a recession for political reasons or whatever. Some of the readers on here just have no idea how huge of a percentage of the population simply will NOT think for themselves due to their exposure to brainwashing through religious and other means, which has now ben highjacked my entities beyond the church.

I mean, I see just how bad it is, even with my otherwise-smart and capable parents. Breaks my friggin’ heart…

This,”if you just watch YouTubers screaming about people living in cardboard boxes and abject poverty, and that’s all you see because that’s all you want to see because it fits into your narrative” could not be more spot-on, and I’ll add that once you do watch one or two of these, YouTube’s algorithm kicks in and that’s all it proffers up. I’ve watched my octogenarian father spiral into this hellhole metaverse. It’s been impossible to get him to pull back on the controls.

Wolf,

“And they’re still pissed off about the high prices.”

I may be about more than higher prices. How about the lower quality of the product. Examples: Just bought some postage stamp size grapefruits for the same price $1.50ea that I paid 1 year ago for full size grapefruits. How about the fact that grocery stores here have eliminated healthy loss leaders like salad bars, and soup bars and substituted processed crap in its place. How about deleting fresh unfrozen fish and replacing that with previously frozen products that you have eat the same day as purchased or it tastes like crap. Or frozen fish flown in from China.

People may not feel secure about SUSTAINING the income around the median. And the prices continuing to rise then become not so affordable.

I have wondered about this as well. I only go on Reddit because I don’t do social media (reddit I’ve been told is anti-social media) but everyone on there is always griping about struggling and Elon Musk’s billions are somehow to blame.

But I own a home. Every one of my friends owns a home. My wife’s friends all own homes, except for one. She’s recently divorced but she’s also an attorney so she’ll be owning a home at some point I’m sure. My brother, who’s a bar back, bought a home a couple years ago.

None of us are rich or come from money. Most, but not all went to college. We’re all in our early 40s so we’re at the older end of the millennials. So maybe that has something to do with it.

I know the inflation stung but my family is in the position that it hasn’t caused hardship. We don’t eat out as much, maybe. I know we don’t do fast food as often. But that’s because it’s gotten ridiculous. I’d rather go to Texas Roadhouse which is just slightly more expensive.

But this is just anecdotal information. I point to things like the low unemployment rate or how wage increases have outpaced inflation. With the highest wage increases going to those at the lower end of the wage scale. I also point to the fact that everyone is complaining about prices but it hasn’t dampened consumer spending. There’s just so much data that says the economy is doing quite well but you have all these people whining about how they are barely scraping by. It’s kind of bizarre.

Andy,

I also do no social media except to post on Reddit and here; even that can suck me in to say things I don’t want to.

Reddit is good for sharing tech info on products or whatever, but turning into click bait, time suck BS (more) since going public.

If I ever post on the community board, I never let it be known that I’m not poor; let that slip, and you’ll have people with multiple fake accounts downvoting everything you ever say.

You will likely come to understand when you analyze where the “fact” that “so many people are struggling” came from.

We really are living in the best of times since WWII that I can recall.

Permanent high plateau…

Wasn’t there a recent stat that it costs more than 30% more to live in the same home vs 2020? Taxes, insurance maintenance etc. This may get even worse as Tax assessments catch up to the growth in value.

And Home owners insurance is up an average of 55% ( pre Hurricanes) which is NOT in the CPI data.

The 22% while a decent stat and really all we can point to numerically, economists agree it’s far from perfect and is understating many Americans “reality”

Disposable income is up and disposable income as a percentage of debt is lower.

However that doesn’t mean people don’t feel financial strain, just not enough to incur debt.

It’s possible people became more conscious of debt but I have my doubts human nature changes that easily.

Or I could be interpreting the definitions Wolf gave very incorrectly…or the other plausible options is that most people are doing fine and the squeaky wheel is just more easily heard

Income/wealth disparity widened between the very top and the middle, but the middle makes a LOT more than before in percentage terms. It’s just that Musk made $300 billion in a few days, whereas in the middle they might make an additional $10,000 a year.

But capital gains are EXCLUDED from this income data in the article. And the super-rich make most of their income off capital gains. The income data here is just the regular income that households have.

I just heard about a study this week that shows a significant statistical uptick in how republicans view the economy coupled with an almost equally lower reading from democrats.

Something I heard said last week: People EXPECT that their wages will increase over time, but they never want to pay more for things.

There are people who are struggling for sure, but they were also struggling before the inflation spike, and some people are always looking for the dark clouds and get pissed off when they see a silver lining.

I’m writing this from Canada where things are not quite as rosy and we have some more problems here, personally my pay bump so far has been easily gobbled up by inflation and I’ve just ended up saddled with more responsibility instead lol. So if anyone should be yelling at the clouds it ought to be me, and I think you guys will find that in the data as well if you look hard enough, sentiment about the US economy is much higher outside the US than it is inside, everyday Americans just want to yell at those clouds with us I suppose

Great presentation Wolfe! From a debt load standpoint, the consumer is great and managing risk! I’d be curious how this looks with non-debt expense % of disposable income (food, rent, insurance, etc) stacked on top to show total expense load % on the drunken sailors. Given inflation, I’m constantly hearing that folks are strapped and living paycheck to paycheck with little emergency funds! Does the government publish this TOTAL EXPENSE LOAD anywhere? Correlation of these ratios with unemployment is also interesting esp when a member of a household loses a job (and disposable vanishes in an instant). I’ve totally been there during the GFC! Keep up the great work!

Median household income in the US is $80,000. This means that half of the household make over $80,000 a year and half make less than $80,000 a year. Of those that make less than $80,000 a year, many make $60,000 to $80,000 a year. So get that into your brain.

There is a lot of stupid clickbait bullshit being circulate in the media about people living “form paycheck to paycheck.” It’s ridiculous headline bullshit, generated by AI or braindead reporters, and published only to get clicks, and for the headline to get spread. No one reads the actual data in those stories that then says the opposite of the headline.

People like you, whose brains got polluted by these clickbait stupid headlines, will never understand why the US economy is doing well, and you’re always surprised by it.

I have shot down this shit before, using the same date that these idiots distort into these “paycheck to paycheck” bullshit headlines that you, yes YOU Pete, titillate yourself with and then drag into here, only to get beaten over the head with data.

SO READ THIS:

“54% have three months of expenses set aside in their account. But 13% can’t pay for a $400 emergency expense.”

https://wolfstreet.com/2023/05/27/americans-ability-to-pay-for-emergency-expenses-or-three-month-job-loss-with-cash-or-cash-equivalent-by-selling-assets-by-borrowing-or-not-at-all/

Jeez Wolf(e), you are the data expert here, which is why so many of us follow – and donate to you. Why is it necessary to excoriate commenters?

Because it’s the same BS – most Americans live paycheck to paycheck, are struggling, and don’t have anything — over and over and over again. Putin propaganda? People apparently have fun spreading it. But they need to post this somewhere else.

I only have two buttons for this to choose from: “delete” or “crush.” I used to have a third button for this: “patiently explain” but it burned out in utter exasperation because people to whom I reply don’t want to know, and they’ll post the same BS again next time they come around. The internet is a strange place.

Wolfe, why doesn’t your reply below have a “reply” button? I’m LMAO at your burned out “patiently reply button.” Too effing true! I kinda want to re-watch Mike Judd’s Idiocracy but pass because I just know it will come across as a documentary that will send me into a spiraling depression…

CH,

No reply button: replies can nest only 3 replies deep to avoid columns getting too skinny on smartphones. So the original comment, reply to original, reply to reply to original, and reply to reply to reply to original. And that’s it

If there is no reply button, go up to the nearest reply button and reply to it, which puts your reply at the bottom of that thread. Make sure to put the name of the commenter that you reply to at the top, as I did here, and as you did [sic], otherwise it gets very confusing.

I want to point out that come January Denver’s minimum wage increase it to $18.81 per hour. That means a couple who can manage to get out of bed on most mornings and go to their full-time minimum wage job and show so little initiative that they don’t get a raise above minimum wage, will still earn $75,240 a year in household income.

Median one bedroom apartment prices in Denver are currently $1,584 per month. This minimum wage full-time couple would be paying 25% of their pre-tax income on rent.

Denver’s Mayor and City Council still endlessly talks about how rent burdened people are in the city, focusing on a household with one minimum wage earner, have with rent on a two-bedroom apartment, with two kids. I’m sure those people exist, and I like for policy to help them grow professionally. However, I reject that that is a representative economic agent of the population, and it should not be the basis of all public policy.

Businesses are leaving the city right and left, and the downtown has one of the worst recoveries in the country, post-Covid.

Those surveys prob are loaded to show maximum effect.

Wouldn’t most ppl just pop it on a credit card and pay it?

The pay in 4 installments is getting a lot of people in trouble with dings on their credit. Cuz they miss a payment.

I agree with you. According to the Republican messaging, this is the worst economy any nation has ever seen, certainly since the Middle Ages. Wolf’s numbers must be wrong, that’s all. His charts are probably upside down.

Now ain’t that some biting sarcasm!

Don’t worry. The economy will be in the best shape ever, starting from the end of January. Known pattern.

Our Great Leader will wave his magic wand and suddenly the worst economy ever will become the best economy ever! Of course the USD is already destroying US exports by making them expensive and making foreign imports even cheaper. With tariffs and higher interest rates, I could see the DXY skyrocking past 110.

LOL! I think you are right about one thing. The phrase: “the data is wrong” is a phrase we are going to be hearing a lot in the future.

40% of middle class renter households are burdened by costs according to census bureau data. Up 20% since 2019…Just one group but there are lots of people not doing well. The idea people are making it up is silly.

Look up what they mean by “burdened” — don’t just throw that word around like a lump of clickbait manipulative bullshit.

So let me help. “Cost burdened” in terms of rent is defined by the Census as spending 30% or more of their household income on rent.

In San Francisco, where 65% of the households are renters, and median household income is $137,000, rent burdened would mean a rent of $41,000 per year, or $3,400 a month (that’s a realistic rent in SF for a nice place). So then this “cost burdened” household has $96,000 a year left to pay for bills, restaurants, school, Teslas, etc. Life is tough as a “cost-burdened renter. ” Even if they splurge on a $5,700 a month luxury rental that costs them 50% of their household income, they would still have $68,500 left a year to spend on other stuff.

30% is a bigger deal if a household makes $2,000 a month ($24,000 a year). So that’s below the “poverty” threshold in the US for a household of 3. And it’s not happening in places where that’s below the local minimum wage. It would be half of the minimum wage in SF, so not happening here. There are not many households that make only $24,000 a year. Median household income in the US is $80,000. That means 50% of the households make over $80,000 a year and 50% make less than $80,000. But humor me…

So if they spend 30% of $2,000 on rent = $600 a month, then that leaves them $1,400 a month to spend on other stuff. So that’s tougher even in a cheap place where $2,000 a month in household income by just one earner might be a little more common. Two earners making $2,000 a month each = $4,000 a month. Then they can rent something for $1,200 a month and have $2,800 a month left to spend on other stuff… so now that’s a little more common. But still a small portion, because half of the households make over $80,000 a year.

Wolf – in your response examples are you pre or post tax when talking household income?

1. pretax cash income. Does not reflect noncash benefits, such as employer-paid health insurance and retirement, free lunches, etc.

2. That was median income for ALL households. Median income for “family households” = $119,400

Minneapolis had a 30% spike in home prices in 2020 to mid-2022 and prices have only edge lower from the peak. Only an idiot would allow the bank to take that home in a foreclosure. If they cannot make the payment, they can sell the home, pay off the mortgage, and walk away with cash. You don’t know the story of those homes, and you cannot draw conclusions from them to the broader economy or the data. Your statement about the six homes reeks of BS that sent my BS-ometer redlining.

Debt isn’t a measure of how people feel about the economy, it’s more a measure of how willing lenders are to stretch and bend their rules for people with poor credit. They were very willing in 2008, today, not so much.

The obvious reason people upset now is the 30%+ increase in the cost of almost everything since March 2020. People have very sensitive and long lived memories relating to consumer prices and inflation really pisses people off. If we have another bout of inflation like that, there will be hell to pay for whomever is leading the country yet again.

You need to get this BS out of your head.

Only a small portion of the debt is originated to people with subprime credit ratings.

16% of auto loan balances originated in Q3 were subprime. But 65% of the used-vehicle buyers paid cash, and 20% of new vehicle buyers paid cash, and those didn’t involve loans at all. So only 8% of all vehicle sold were to people with subprime loans. And many new vehicles were leased to people with high incomes and credit scores because it suits their lifestyle or business.

Only 3.5% of the mortgage balances issued in Q3 went to subprime-rated borrowers.

debt aside, he’s right that people are upset about the 30% increase in the cost of everything, and that’s why they perceive the economy is bad.

If it was just a Republican message and not reality for a lot of people, election results may have been different.

It’s all just data, but election data suggest people don’t feel as good as numbers show, right or wrong

The messages mostly were originated from Moscow, via social media. Same as claims that people were sitting in cold homes starving in EU.

In St Petersburg, there is an entire complex full of worker bees whose sole job is spreading disinformation on social media. They work in league with certain US media organizations to ensure that the American public digests a non stop diet of lies.

Of course, physically the troll farms are located mainly in Leningrad. There also more east, e.g. Nizhny Novgorod.

I just did a mental shortcut.

But this is not just trolls. RU has sent $ to the right wing US organizations.

I think the only truth here is “Don’t trust the internet” ask your friends, family, and neighbors how they feel about the economy. Location, location, location is not only the most important thing in real estate, it applies to the price of everything from eggs to gasoline.

The truth on the ground in Boise is not the same as Des Moines and sure as shit has no relation to San Francisco.

The money that drives prices in our largest cities has little to do with life in second and third cities and is completely disconnected from rural life.

The pandemic, remote work, and massive demographic shift of baby boomer retirements has driven housing prices more than increases in income.

We are still struggling with the silly amount of money sloshing around from stimulus and the above mentioned changes spilling big city money into other markets. That may never end as long as foreign money is laundered through those big city markets.

Inflation is our future (woops I meant high prices).

And the Republicans won big time.

Let people/corporations go bankrupt FFS. Prices will come back down to earth. The 50+years for privatizing profit and socializing losses needs to END. Fuck em.

WB,not sure exactly what you are getting at,could you be a little more clear on your message?!

Call me “old fashion” but it might also be a good idea to start prosecuting FRAUD as well, and actually put some fuckers in prison. It’s interesting because the people opposed to such ideas are the same people that try to sell you fancy financial “products” like mortgage backed securities. Essentially everyone, including turbo Timmy, eventually admitted that MBS was essentially fraud under the law at the time (of course the bankers lobbied and changed the laws), yet no one, less one low-level trader, actually went to prison. See the problem yet?

Since most loans are bought or backed by the GSEs, here is some interesting info:

Debt To Income for purchased house loans at the GSE has been trending up YOY

How much can that ratio be? According to the FHA official site, “The FHA allows you to use 31% of your income towards housing costs and 43% towards housing expenses and other long-term debt.” Conventional loans are usually 28% and 36%.

• In the 1950s, FHA had an average DTI of 15%; in 2023, this has now risen to 31%.

• By allowing higher DTIs, FHA constantly pushes up home prices in a supply-constrained market. This is indicated by the long-term trend during sellers’ markets that fastest HPA growth rate is at the low end.

There is an other metric called HDTI. This includes the property tax and insurance in the mortgage payment DTI calculation. Freddie and Fannie are sitting at 38, up from 33 ten years ago. But FHA is at 46%!

46% means you do not have a lot of wiggle room if you do not have an ample amount of savings when an emergency comes up like a big medical bill, car repair, job loss, etc.

I guess one could always tap Home Equity which has ballooned in value?

At 46%, one is house poor unless your income in extremely high, high enough that the tax burden at that income also ceases to really hurt your lifestyle much, if at all.

People will never learn. These programs for “housing affordability”, drive up prices. Derp! That’s economics. More demand while no new supply.

The same is true of every gosh darn government assistance. Inject money, prices go up. Price go, must need to inject more money! Derp! Derp! Derp!

Regarding the DTI ratios you cite, is it gross income or income after tax in the denominator??

gross income pre-tax

Interesting. 46% of gross income is something like 55%-70% of income after all taxed including fed, state, payroll tax, RE tax, etc.

Giving people loans with DTI’s of 46% is insane. No wonder some of these loans are going into default within a year.

One other note to remember, one person’s debt is another person’s asset. Wolf can correct me if I am wrong (and I am sure he will), but that interest can (and will) be spent by someone, so it can be argued that higher interest rates, especially on the short end of the yield curve may contribute to inflation.

“Everything you know is Wrong!”

“We are all Bozos on this bus!”

Fixed income folks are getting hammered. I know 3 people who could afford an apartment, but no longer can. 2 rented rooms and 1 is trying van life.

“Fixed income folks are getting hammered.”

That’s incorrect. So I’ll fix that for you: “Folks on LOW fixed income are getting hammered.”

I knew a guy who’d been homeless for decades (haven’t seen him in a while). We used to chat. It’s tough. He did some gigs for lawyers and sometimes stayed in cheap motels off season where he knew the owners, paying just a small amount. You gotta have some income. And you gotta take care of your retirement during your working life. If you fail to do that, it’s tough, and you’re going get hammered. Everyone knows that.

MW: A surging U.S. dollar is hammering emerging-market stocks and metals. Watch out.

Have student “loan” repayments restarted? Are the balances now accruing interest?

Curious about the latest on all that.

Really?

It looks like most everyone is servicing their debt okay. Only household debt resulting in collections, delinquencies, foreclosures, and bankruptcies matter. I am in debt every month. I buy everything with a 5% cash-back Instacart card, a 5% cash-back Amazon card, and 2% cash-back on everything else. But I always pay it all off on time. Wolf has talked about this issue from time to time.

Slightly off topic, but important. Powell said at a Dallas Fed event today that “the economy is not sending any signals that we need to be in a hurry to lower rates.” Uhh, dropping 50 basis points in one meeting and 25 the next sounds like someone is in a hurry to lower rates. Powell needs to check into a clinic to get tested for early signs of dementia. In this universe, x does not equal -x.

But those rate cuts already happened in the past when he said that today. Not like he can go back in time and undo them.

Lets see what happens at the next meeting – I think there’s a good chance we get a pause instead of a cut.

The economy was just as strong two or three months ago as it is today. Powell dropped rates 50 BP because Senator Warren gave him a much publicized letter that wanted a 75 BP cut. Maybe now that her and her cronies’ power is much diminished, as in almost non-existant, Powell decided he can tell us what he really thinks. Either that or he is suffering from an early stage of dementia, as I suggested.

Here’s another way to look at it: Powell wants to normalize the yield curve, which involves QT to bring up long-term rates, and these gentle rate cuts to push down short rates a little.

5.5% T-bills were a treat, but remember this the risk-free rate that credit & duration risk are priced against. It makes sense that the risk-free rate would be a little lower, whereas the 10y treasury should yield around that for the duration risk.

They need to lower rates to lower the federal government debt burden, so one way or the other, rates are gonna come down.

What justification they use for it, that’s anybodys guess

With good credit doesn’t hurt to work the system. Every year I get a new credit card with $200 or more cash bonus, rewards and 12 months or more of 0 APR. Doesn’t amount to huge amount but $400-600 a year or even double that not bad for just rotating cards. This will decline in value as rates get cut however.

If things are so wonderful, why did Trump get elected and also win the popular vote ?

Blaming it on people being pissed off about higher prices just seems to be another version of “deplorables don’t know whats good for them”.

I do agree you make a good case for the personal debt burden not being unbearably heavy. But does that really tell us that everything is dandy ? Maybe there is just an entire cohort that is excluded from debt markets all together.

You did a previous article about how costs are pushing people to see renting a house as preferable to buying. Ditto with car ownership. Many young people don’t want a car because it’s so expensive, but that means they must live in an urban center of some sort. Good or bad ?

Work from home also makes that more possible and practical for those who don’t want to live with such population density.

For myself, the changes of the last 2 or 3 years have not been severe but I do find myself squeezed and looking to cut costs and/or raise rents to cover costs I’ve absorbed in property taxes and insurance, water/sewer, repairs and landscape maintenance.

The loss of interest income will probably have a bigger negative impact on me than prices increases which I could mostly avoid.

Statistics paint a very low resolution picture but I appreciate the clear picture you continue to provide.

As a statistician, economics major, and private investor, it is refreshing to read Wolf Street. His honest, straightforward presentation of data is incomparable. There is nobody better out there than Wolf Richter. I follow a lot of “sophisticated” financial observers, but Wolf is my “go to” guy for all things data related. Does that mean I always agree with his interpretation of the implications of said data? Well, sometimes. But I must admit to being a bit of a skeptic, and am currently sitting mostly on the sidelines with T-bills. It is hard for me to convince myself that blowout fiscal deficits with the funds being directed by government “experts” is ultimately beneficial to our economy’s long-term growth prospects. I am also wondering aloud how it is sustainable to pay interest on the current government debt at 4% or so. That does not seem sustainable. And then we have a historically over-valued stock market by many traditional measures. I particularly like looking at P/E ratios using past earnings, because I don’t trust any company to accurately predict future earnings. And those “trailing” P/E numbers look concerning, especially for Big Tech. So, where does that leave me? Worried. Yes, very worried about what lies ahead. So, despite Wolf’s assurances that the average American is in “good shape” financially, I am wondering if this is sustainable. Our economic system has become very “financialized” over the past 40 years. We don’t make stuff like we used to. And the idea of “reshoring” seems to me to be a bit overly optimistic. It is not simply a matter of throwing money at the problem. There is the issue of education, training, and experience. Even in today’s modern economy, making stuff efficiently with high quality involves a lot of skill and talent. That takes time to develop. So, while I agree with Wolf that, on the face of it, consumers are overall doing okay, I am not sure that the future is very bright for many folks.

Just an observation, not a criticism: You’re a statistician, private investor, and ECON major, and sound like a smart cookie; yet by your own admission, you follow “experts” who almost certainly don’t know anymore than you. We are wired to seek consensus, yet that is rarely where the money lands.

Many will thrive and many will fall behind. Mostly, we grind it out or get lucky. Opportunities are obvious in hindsight.

I got lucky. Just happened to start buying rental properties in 2014. I also bought gold instead of Bitcoin in 2010 so…

I am unaware of any pundit interpreting data as concisely as Wolf. It’s why I read here. Tune out BS and get a feel for overall direction. He would have to share how well that translates to big investment payoffs with rapid scaling of wealth.

I thought 2020-2023 was insane. The great implosion was impressive. But, again, I stuck to my plan and didn’t buy NVIDIA.

It’s a wonderful falsehood to confuse investing acumen with catching a break. P/E ratios have not meant much for some time. They’re outrageous. If you break the code and somehow hit ALL home runs, you may be on to something.

Being skeptical is good, it’s protective and rational. But don’t worry so much. Most of it is beyond our control.

Please use exactly the same email each time. Anytime even one character changes in your email, it’s a new email and goes into moderation.

I was going to Netflix and chill but decided to Wolf Richter and debt thrills.

One item that this isn’t capturing is the American dream – yes most Americans are stable where they are, but can they get to where they want to be ? Is household formation up or down ? Are people delaying having kids to avoid increasing costs and taking risk ? Is a major segment of the pop staying unhappily in smaller abodes instead of moving to larger places?

It’s one thing to be not cost burdened, it’s another thing to be happy about it.

Again, I think social media has fucked with the all our heads and sense of scale and averages (& medians). We should have massive campaigns about the average American life and squeeze out the outliers just so most of us can feel better about where we are.

As for GDP – in one sense bring an average yankee skeptic, RFK jr junior scares a little bit of shit out of me, however, I am also thrilled about someone willing to fix our fucking health.

Can you throw some stats on the cost of our shitty health on GDP? How much of our national debt is health related and out of that how much is related to preventable issues?

I have an unsubstantiated belief (hope?) that if we get healthy physically (reduce intake of shitty food) it will quickly impact our GDP and also Americans sense of well being.

In the next pandemic, and yes, there will be one, there will be no vaccines or measures to stop the spread. Just you and your immune system! Good luck, suckers!

I doubt it. Those vaccines were the “Trump vaccines,” one of his biggest accomplishments, but then he let the anti-vaxxers in his base steal that accomplishment from him. I never understood why he let them do it. Trump himself got vaccinated.

I just got my Flu shot and recent Covid vaccine. The flu shot knocked me out 1 hour after taking it. Took 1 day to recover. The Covid shot was much better. No side effects, like the ones in 2021.

Government debt is household debt, given they’re the ones who will be paying for it through inflation or tax. Government spending has a tendency to crowd out other credit forcing others to deleverage. Households can look sparkling when their debt is transferred to federal balance sheets through various debt forgiveness schemes, bailouts and QE. Federal Government debt is the real brewing crisis when they’re racking up 7% of GDP in annual deficits.

Could some of the bad economy vibes be coming from people who could have afforded a home, but cant because of the money printing & zirp after the pandemic, besides other factors ? I.E people like me.

Luckily, I have a decent job and got a 3.5% pay increase and a bonus this year. I slogged for it. In late 2019, WE planned to buy a modest home in a decent place by 2021. The pandemic hit and home prices went up by 50% or more in my area. My wages did not go up by 50% or close. Lots of people who were waiting to buy 2nd homes a few years later got it during covid thanks to zirp.

Now current home prices have dropped by 10% or so (not near 50%) which is still to high. My area still remains attractive to US residents including well off Californians, Chinese investors and PE crooks. So yeah, I am unhappy about housing only.

DA – “Could some of the bad economy vibes be coming from people who could have afforded a home, but cant because of the money printing & zirp after the pandemic, besides other factors ?”

Emergency actions around covid — sparking fears of job destruction — helped price you out of the market. So your complaint should be against dirigiste fiscal and monetary policies (managed money enabling budget deficits), which has worked against you.

My family and I bought our first home decades ago when home prices vs earnings were lower, but when interest rates were much higher. We were then effectively subsidized through falling mortgage rates, allowing us several refinancing opportunities. My family and I were fortunate, in that respect.

My beef with “managed money” centers around the unintended but predictably destabilizing side effect of its unintended consequence: systemic leverage. The huge debt build-up caused by monetary and fiscal management (price fixing interest rates, and continual deficit spending) can only end a couple ways: jobs depression and/or chronic inflation.

Unemployment drifting upwards will be the canary in the coal-mine. Newton’s third law concerning equal and opposite reaction will likely make an appearance, IMHO.