Rate-cut-mania soothed the pain, but it’s over.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

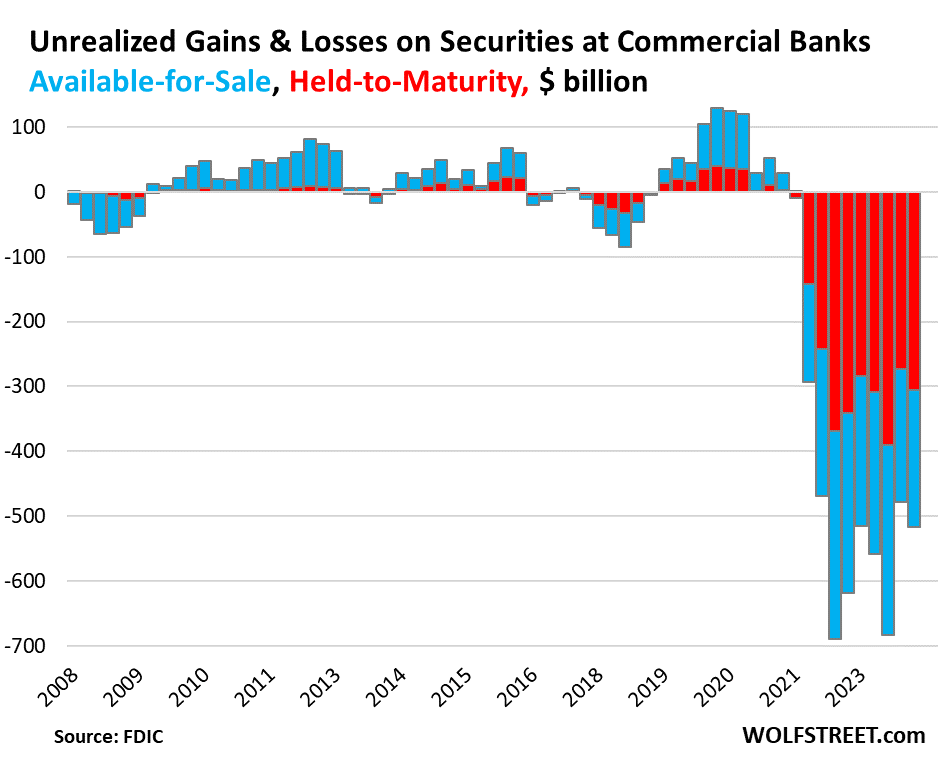

In Q1 2024, “unrealized losses” on securities held by commercial banks increased by $39 billion (or by 8.1%) from Q4, to a cumulative loss of $517 billion. These unrealized losses amount to 9.4% of the $5.47 trillion in securities held by those banks, according to today’s FDIC’s quarterly bank data for Q1.

The securities are mostly Treasury securities and government-guaranteed MBS that don’t produce credit losses, unlike loans where banks have been taking credit losses, particularly in commercial real estate loans. These are pristine securities whose market value dropped because interest rates rose. When these securities mature – or in the case of MBS, when pass-through principal payments are made – holders of these securities are paid face value. But until then, higher yields mean lower prices.

These unrealized losses were spread over securities accounted for under two methods:

- Held to Maturity (HTM): +$31 billion in unrealized losses in Q1 from Q4, to a cumulative loss of $305 billion (red).

- Available for Sale (AFS): +$8 billion in unrealized losses in Q1 from Q4, to $211 billion (blue).

HTM securities (red) are valued at amortized purchase cost, and losses in market value don’t hit income in the equity portion of the balance sheet, but are noted separately as “unrealized losses.” It’s with these HTM securities, and HTM accounting in general, where the problems reside.

AFS securities (blue) are valued at market value, and losses due changes in market value are taken against income in the equity section of the balance sheet.

Rate-cut-mania soothed the pain, but it’s over.

Yields on longer-term securities began plunging in November and bottomed out early this year amid general Rate-Cut Mania. The plunging yields caused prices to surge, which caused the unrealized losses in Q4 to drop from the massive levels in Q3.

But in the latter part of Q1, Rate-Cut Mania began to subside, yields rose again though not back to October-levels, and so the unrealized losses in Q1 rose as well.

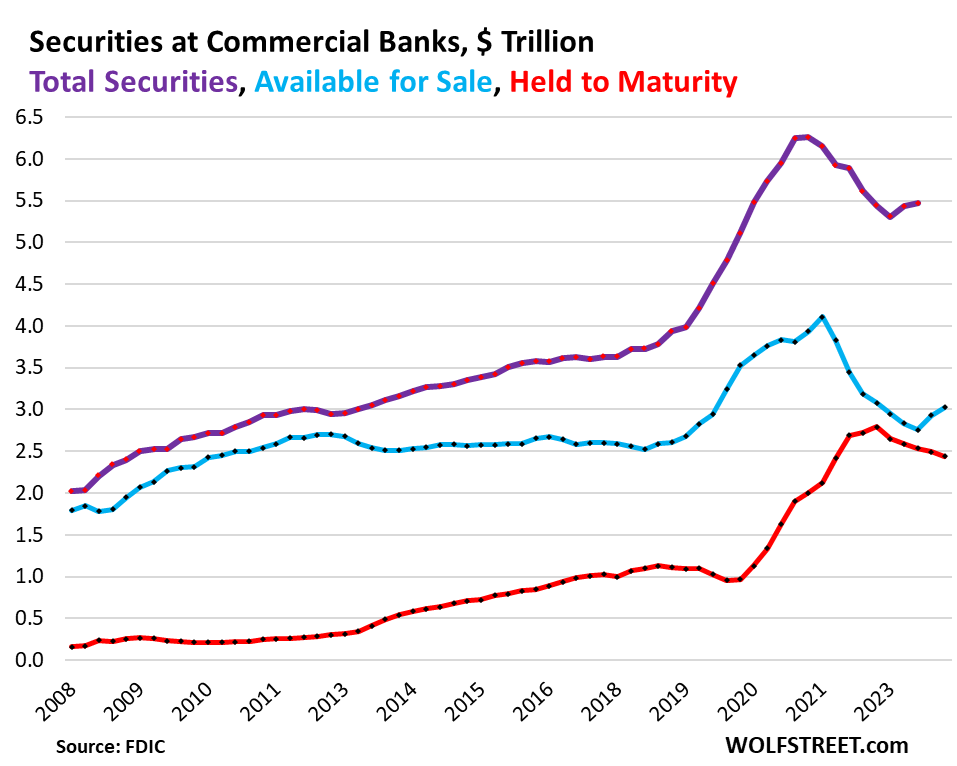

The $5.47 trillion in securities held by banks.

During the pandemic money-printing era, banks, flush with cash from depositors, loaded up on securities to put this cash to work, and they loaded up primarily on longer-term securities because they still had a yield visibly above zero, unlike short-term Treasury bills which were yielding zero or close to zero and sometimes below zero at the time. During that time, banks’ securities holdings soared by $2.5 trillion, or by 57%, to $6.2 trillion at the peak in Q1 2022.

That turned out to have been a colossal misjudgment of future interest rates. The misjudgment already caused four regional banks – Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, First Republic, and Silvergate Bank – to implode in the spring of 2023 when spooked depositors yanked their money out.

In theory, “unrealized losses” on securities held by banks don’t matter because at maturity, banks will be paid face value, and the unrealized loss diminishes as the security nears its maturity date and goes to zero on the maturity date.

In reality, they matter a lot as we saw with the above four banks after depositors figured out what’s on their balance sheets and yanked their money out, which forced the banks to try to sell those securities, which would have forced them to take those losses, at which point there wasn’t enough capital to absorb the losses, and the banks collapsed. Unrealized losses don’t matter until they suddenly do.

The value of securities held by banks ticked up in Q1 to $5.47 trillion, after having already ticked up in Q4, but is still down by $786 billion, or by 12.6%, from the peak in Q1 (purple in the chart below).

HTM securities have declined steadily from the peak in Q4 2022, and dipped further in Q1, to $2.44 trillion, down 12.7% from the peak (red).

AFS securities rose for the second quarter in a row, to $3.02 trillion but remain 26.4% below the peak in Q1 2022 (blue).

Several factors make up the decline of securities on bank balance sheets from the peak, including:

- The portion of securities of the collapsed banks that the FDIC sold to non-banks are no longer part of it.

- Banks have written down AFS securities to market value.

- Some securities matured.

- Banks may have sold some securities.

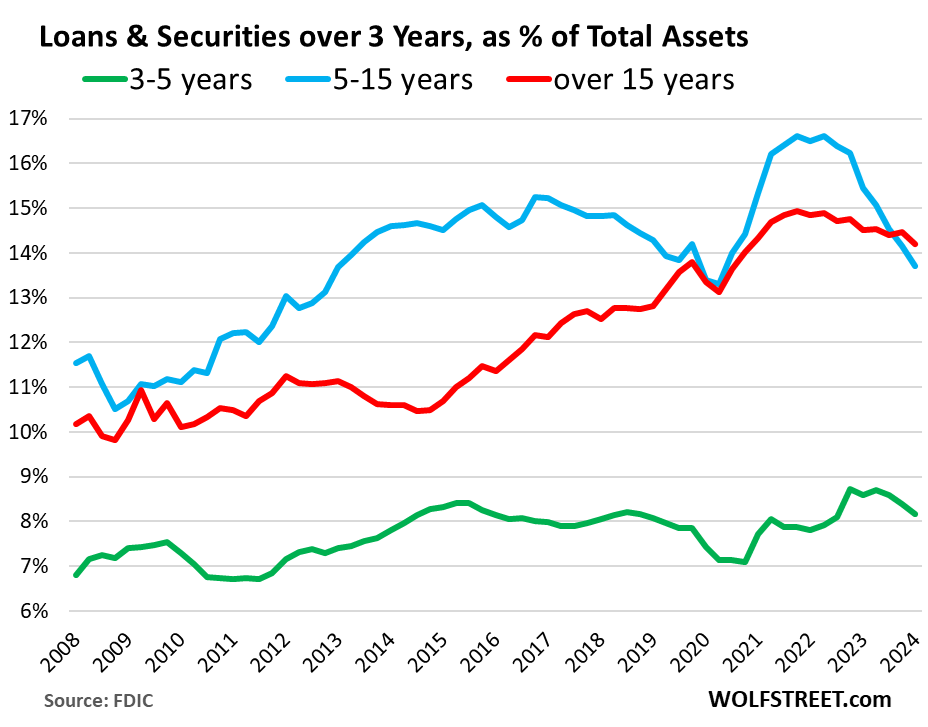

The longer till maturity, the bigger the interest-rate risk.

Interest rate risk — the risk of falling prices as yields rise — increases with the term of the security or loan. The 30-year Treasury securities sold in the summer of 2020 have lost the most in market value, while 5-year Treasury securities sold at the same time are now just a year from maturing and are trading at small losses from face value.

To gauge this risk on bank balance sheets, the FDIC provides data on securities and loans by remaining maturity:

- Least risky (green): 3-5 years: 8.2% of total assets.

- Riskier (blue): 5-15 years: 13.7% of total assets, lowest since Q2 2020, after substantial declines.

- Riskiest (red): 15+ years: 14.2% of total assets, lowest since Q2 2020.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

So knowing all of this what keeps the 30 and 20 year yields lower than the shorter term treasuries. As a novice it’s made no sense to me. Why would investors not demand higher rates for long term risk? I read somewhere we set or are about to set a new record length of time for an inverted yield curve.

Really, none of it matters. If another stress event popped up old G-men would step in and backstop with tax payer money. Remember old Joe on TV saying banking system was fine. More interest in that QB battle you’ll have out there in pittysburgh.

In the four regional banks that imploded in 2023, bank investors got wiped out. Only uninsured depositors got bailed out.

And it wasn’t the taxpayer that paid for the depositor bailout, it was big banks; they have to pay the FDIC a special assessment to cover the FDIC’s losses.

At the end of the day, it is end customers/consumers/clients/common people/tax payers paying the bill for making uninsured depositors whole.

Even if bigs banks are paying fine, big banks would make sure it comes out of someone else’s pocket.

The Special Assessment levied on the biggest banks is indicative of the seriously inadequate FDIC Insurance Fund. You’ll be shocked how small it is.

I don’t know what the future holds. I do know that the financial affairs of the country are in a very vulnerable state.

Charles Jacobs,

Special assessments are standard when the FDIC takes bigger losses.

Actually, the losses the FDIC ultimately took on those three banks that it took over weren’t that huge because those banks came with lots of assets, and it has been selling those assets to cover the costs of the deposits it bailed out. It’s only the shortage that the FDIC fund needs to cover: backstopped deposits minus proceeds from asset sales.

I remember at the time of SVB etc. folks were panicked over how uninsured depositors needed a bailout – but that in reality they would all mostly be made whole through the sale of the banks assets. Knowing this – why the bailout? Why not let the system work? Companies with large uninsured assets (payroll? etc) could have gotten financing from other banks to make payroll and ultimately would have only taken a small loss. Let the system work as designed.

grimp,

“Let the system work as designed.”

Yes, totally agree. But of all the stupid things they could have done, such as bailing out investors, they did the least stupid thing.

Lots of wealthy investors’ startups and young companies had huge amounts of cash on deposit at SVB; it was all concentrated in that scene, they were well-connected and rich, and for some reason, they could not be allowed to get a 20% or whatever haircut on their deposits. There was never any reasonable justification for that.

When SVB first went under I disagreed with the idea of bailing out customers who had more than $250,000 in deposits. I wanted to see the process work itself out. I was actually kind of hard-core against the bailout.

I have come to change my mind when I learned new information.

I came to re-learn and old lesson. Sometimes it isn’t just about the amount of money involved, it is also about the timing of access to that money.

From everything I have seen, after the sale of the assets of SVB, most depositors would have eventually been made whole. The losses per depositor would have been less than the $250,000 FDIC insurance. I have never looked close enough tobget the actual numbers, but from everything I have seen, it would have been close enough. At worst big depositors (over $250,000) would have lost a few percent.

The problem was in the timing of these losses. If things were allowed to play out normally, it would have taken months for the depositors to be made whole (or close to whole). The problem was, that would have really hurt a lot of the depositors because they would have had to wait months to be made whole on accounts that were used for payroll.

So companies would eventually be made whole (or very close to it), but they would have to wait months for the process to play out. Meanwhile the company goes under and all of their employees get let go and/or not paid. That would have huge economic effects.

Basically the decision to immediately back all deposits 100% traded a few percent (at worst), maybe less, of potental loss for timeliness of keeping the customer startups going as an ongoing concern.

Now I don’t think this was a bad decision.

Everyone knew the rules regarding the limit for FDIC insured funds. Bailing out uninsured deposits is BREAKING THE RULES. Just like buying MBS this was WRONG. The Fed’s charter needs to be revoked.

The level of moral hazard that has been released by The Fed and their political puppets is staggering. It’s no surprise to me why the average working man and women are so pissed. There will be consequences to the continued socialization of private losses and bad behavior by the politically connected. The longer this goes on, the more unpredictable the consequences.

moral hazard

Yellen is issuing most of the Treasury debt at the short end, taking advantage of the large balances in the reverse repo facility.

This is highly unusual for so much of the issuance to be so short term and is skewing the yield curve.

Plus, there are whole lot of people who are 100% convinced that the market will crash and the QE bazooka will return, buying bonds and driving yields much lower. Wolf seems to think the Fed won’t do that. I have no idea, but I’m 100% certain that even if it does happen, most will not be able to sell their long bonds and bank that capital appreciation before inflation (and massive issuance from a broke government running even more historic deficits) pushes yields much higher (and thus bonds lower). I can even forsee a scenario where the fed cuts the short end and long end yields go up instead of down.

I can’t see any reason why I should be interested in the long bond. T-bills for my spare cash is working fine. By the time yields get cut sharply, there will be bargains to be had in other markets.

I agree. It is going to get interesting when the treasury tries to roll over the debt that is maturing this summer. I don’t see the yield curve uninverting any time soon.

I wouldn’t count on QE returning anytime soon. The bond market is very dumb right now. If it ever sinks in that interest rates will remain higher for longer the curve will normalize and long-term debt will make sense. It doesn’t now.

I believe Ms. Yellen competing with the Fed through the issuance of T-bills to fund government liquidity needs is what is skewing the short end of the curve so intensely. Treasury must borrow at competitive rates since the market for sovereign US debt is drying up.

This is an excellent question, and one that many experienced financial observers are confused by. Until it is pointed out to them that the bond market is completely broken due to the Fed owning such a huge chunk of it. How can you have price discovery if the Fed is manipulating the market?

With HTM there are indeed economic losses because the banks now have to pay higher interest rates to depositors. Therefore all else being equal liabilities (deposits) are increasing at a faster rate than assets (which are going to mature at face value) which means equity is shrinking.

I’m holding a large amount of 30 yr treasury bonds and wonder if I should get out now?

When do they mature?

Howdy MJ Your answer is available after a small donation to the Bubba Squirrel Foundation.

I’m In!

Are you comfortable holding till maturity?

Wolf,

Do you think the recent drops in the Dow (financials heavy) are explained by these accrued losses?

Also, do you have any opinion about the extent to which shadow banks are taking business away from traditional banks, and whether the shadow banks are suffering from similarly gorging on low interest long term bonds?

“Shadow banks” are non-bank lenders, meaning they cannot take deposits, so they don’t have access to cheap cash from depositors, so they don’t sit on a lot of cash they have to invest, so they never bought long-term Treasury securities.

Instead of cash from depositors, they have a big credit line (warehouse line of credit) with big banks that they use to fund new mortgages they write. After a while, they sell those mortgages to Fannie Mae et al. and use the proceeds to pay down their warehouse line of credit. And so they have credit available to write more mortgages.

So interest rate risk is not a problem for them. But they’re highly leveraged and are exposed to other risks. The top mortgage lenders in the US have been non-banks. But they’re not regulated by the Fed or the FDIC, and they’re not backstopped by them either. So eventually, one of them is going to blow up, and it’s going to be somewhat of a mess, but at least they don’t have depositors, and the mess would be more limited. There is some contagion to the banks via their warehouse lines of credit, but these are secured by the newly written mortgages, so the losses for the banks won’t be huge.

Do you have a sense of what industry/geographic risks they are concentrated in?

Obviously homebuilders is a major subset, but I cannot help but think that one of these shadow banks is financing NVDA chip purchases, or engaged in something else that is only going to be seen to be high risk in retrospect.

Thinking back to Enron, I can’t help but think there are a few other shadow banks mixed up in some similar shenanigans, all thinking they will get out and someone else becomes the bag holder before the music stops…

Don’t focus so much on the word “shadow”. Call them “non-bank lenders” and reread Wolf’s comment.

Recognize that in China, “shadow bank” means something much closer to what you are talking about, and is a major risk in their structure.

The capital markets in the US are pretty transparent.

Enron was about fraud so deep that the outside auditors were implicitly part of the fraud. Banks are stupid sometimes, but not so stupid as to loan if they had any hint of that.

Now investment banks – the ones facilitating bond deals – they might do something like that, but only because they are the middle man rather than actually holding the bond.

Excellent summary. One potential source of trouble for some of these leveraged private equity funds are the loans they are making to troubled CREs. They are doing their usual routine of “reaching for yield”. As you astutely pointed out, at some point, this is going to have a bad ending for some of them.

So while the banks offload long dated low yielding Treasuries and buy higher yielding paper, their balance sheets should square up especially if bond yields remain the same, or drop. The problem isn’t commercial banks its regional banks, who were caught up paying the Feds rate hikes to depositors and who did not have access to RRPO. FHLB is also reliant on real estate loans to cover their members. RRPO is winding down, but rate hikes are not, so commercials have to pay overnight funds rates to depositors while bond yields are lower. What it all means is that an emergency rate cut will happen and markets are not going to like that. Dropping the rate at the short end will not bring the long end down. YC remains inverted.

Wolf:

The 2023 numbers look humongous compared to the 2008-great recession (even after taking into account the loans, assets must have increased – looks like doubled from the bottom graph ). What is happening. Not just our citizens have become a drunken sailors but the institutions too!

What happened is that during the 2020-2022 QE, which was gigantic, the banks ended up with trillions of dollars in new cash from depositors that they had to do something with, and so they bought these securities.

It’s the Fed’s fault, that’s for sure. If the Fed hadn’t done $4 trillion in QE over those three years, the banks wouldn’t have ended up with trillions in cash from depositors and wouldn’t have had to invest it.

It’s also the banks’ fault because they believed the Fed that this 0% interest-rate craziness would last forever.

So one of the reasons for the drop in balances is because “some securities matured”. Is that to say that they are maturing and not being replaced as cumulative deposits are reduced and that is because QT is doing its job of removing some of those deposits from the system? Or shouldn’t it at least work that way in theory?

Yes, deposits coming down as a result of QT or a shift to money market funds is a big factor.

Unless there is a pressing need for the excess liquidity, HTM should be the policy across the board, unless there is certainty of higher returns on the table.

Why? I’m a bank treasurer with no pressing liquidity needs and I carry everything AFS and nothing HTM.

The problem is you don’t know when a pressing need for liquidity will arise.

Mark2market is the only honest way to assess a bond’s value. The difference in price between market and par represents some of the yet-to-be-accrued interest.

The biggest risk is being in 90 day T-bills instead of being in long term bonds. How people can continually get this wrong I’ll never know?

How would that be the biggest risk? You can always buy longer-term debt. There is no shortage of it. Right now, T-bills yield is nearly 1 percentage point higher than yield on 10-year debt. These things don’t change that drastically overnight.

90 day TBill is the least risky thing: As good as cash but with yield of 5% plus.

A 10Y Bond is very sensitive to rates. 1% increase in 10Y bond may bring its value by 10% or so.

No such exist with 90 day TBill.

Real Tony,

Take a look at a 5 year weekly chart for TLT (an ETF serving as an analogue for Treasuries with 20 to 25 years to maturity on average).

It has been in a bear market for 4 years (YES– 4 YEARS). It is down by almost 50% in nominal terms, and much more than that inflation adjusted.

That is what interest rate risk looks like, and what it can do to a portfolio.

This is the reason that the 60/40 portfolio has been falling out of favor.

TLT should be $85

Mr. Wolf’s comment:

“When these securities mature – or in the

case of MBS, when pass-through principal

payments are made – holders of these

securities are paid face value.”

From this statement it appears the key for banks realizing those unrealized losses is to make sure the MBS doesn’t get paid.

Your statement doesn’t make sense at all.

Most of the MBS are held not by banks but by GSE thus tax payer on the hook for any loss.

If banks are holding MBS/Bonds, say yield is 3%., then they are sitting on un realized loss as rates have gone up quite a lot. If and when they sell before maturity or before pass through for MBS, they’d realize the losses.

If they sit tight till maturity then they didn’t lose anything but just opportunity cost.

i don’t think you are right. the taxpayers are guaranteeing the payments on the mbs, but not the risk of loss from rate creep. in other words, if i buy 10,000 usd worth of guaranteed mbs with a 3% coupon, the government is guaranteeing that i’ll get my 3% coupon and the principal back at maturity.

if rates rise to 7% and the 10,000 drops in value to 8,000 because of mark to market, that 2,000 loss is not guaranteed.

On this website, it’s years that the end of the financial world is closer and closer. I don’t blame Wolf, but his avid readers.

As a matter of fact, this is the niche (market share of readers) he realized to be very successful in.

And everybody, as it should be, is aligned.

It’s almost unbelievable, but … true.

I really love your work, but there’s still time for the Armageddon.

When it’ll come, you’ll finally say everybody : “I told you for years!” :)

Thanks,

Donato

RTGDFA

Not Wolf but some commentators. I’m not one of them. I’m an avid reader.

Wolf,

TLT (20+ year treasury ETF) is now down from its all time high in mid 2020 by 48% nominal, by 58% inflation adjusted (according to CPI statistics).

At what point do people start to care?

People will learn to hate bond funds? People should only use these types of funds for directional bets on interest rates. Bond funds are not “conservative long-term investments.” If a broker sold it that way, they should be sued.

But if you hold the bonds outright, and bought at auction, you gripe about the low coupon interest, and at maturity, you’ll get your money back. That won’t happen with bond funds.

Shouldn’t it be the same? Those funds do hold actual bonds so if you hold the funds for the same amount of time, it should reach the same value.

Some bonds will mature and get replaced over that interval but those new ones pay new rates.

It’s just difficult to look at your statement and see the unrealized loss every month.

“Shouldn’t it be the same?”

No, and this is a huge and very common misunderstanding of what bond funds are, and how their structure makes them far riskier than the underlying bonds. They have all the risks of the underlying bonds plus the risks of the bond funds themselves (run on the fund, forced selling, investors bailing out at low prices, thereby locking in those low prices because the fund cannot hang on to those bonds, etc.). Wall Street has been mis-selling them in bold print for decades, while disclosing their risks in small print in the footnotes that no one reads.

Bond funds became popular during the great 40-year bond bull-run, which ended in August 2020. During that time, interest rates kept going down, and bond prices kept rising, so the problems bond funds have were largely painted over by rising bond prices. But a bunch of big ones blew up during the financial crisis, and some during the Great American Oil Bust (2014-2016), and investors got massive haircuts, in many cases of 70% losses.

I like bonds, I hate bond funds.

Money market funds are also bond funds and they have the same structural problems, but those problems are mitigated by their type of investments: very liquid short-term instruments with less than one year maturity, including a lot of overnight repos and very short-term Treasuries. If they encounter big issues that trigger losses, they will “break the buck” by a couple of cents of so, meaning losses of a 2% or 3% or whatever, so small compared to longer-term bond funds.

So I’m not concerned about money market funds, but I do think that people should not put their entire life savings into just one money market fund. T-bills on auto-rollover (either through your broker or at TreasuryDirect.gov) are ultra-safe and fairly easy alternatives with higher yields, zero risk, but less easy to convert to cash than money market funds.

Not the same at all. If interest rates rise, people will sell their fund holdings forcing the fund manager to sell the underlying bonds forcing you to take the loss.

Long-term bond funds kill you when interest rates go up.

Bond funds have no pull to par.

Imagine a Treasury bond that, everyday you look at it, has a maturity 20 years from the current day. In other words, the maturity date never gets closer.

That’s basically what TLT is.

“Bond funds have no pull to par.”

But they do. The new bonds replacing the matured ones will be added at today’s return rate (aka “par”), thus bringing the average closer to that rate. Eventually, they all get replaced.

Thank you for validating my understanding, Wolf. People I am close to have been advised into Bond funds / ETFs “for low risk” which really upset me, but it is hard for me to explain in a way that overrides their salesman advice that funds have totally different risk/reward profiles than owning bare bonds.

Now is when the quality/integrity of bank management is really tested.

If the accounting of the difference between HTM securities and for sale securities was genuinely true, then the bank will probably do fine. If the difference was used as a slush fund account to adjust reported GAAP earnings, then the bank is probably struggling.

For those who know, the tide has gone out, it is time to see who was swimming naked.

The banking/finance sector of the eCONomy hasn’t had integrity for years as it has been patently clear for some time now that they can simply buy CONgress and change the rules. In addition, the Fed can simply move the goal posts when it come to the metrics that they supposedly use. For example, why is the definition/equation used to measure inflation constantly being modified? If the Fed were truly independent, this would not change as the items that people require for survival and prosperity haven’t changed. It’s ALL political theater now. Same old human flaws as people lie, cheat, and steal their way to power now refuse to give up that power and do anything and everything to stay in power.

Interesting times to be sure. Plenty of opportunity out there now, as more of the world is seeing things for what they are.

“Held to Maturity (HTM): +$31 billion in unrealized losses in Q1 from Q4, to a cumulative loss of $305 billion (red).”

Just playing around with these numbers vis a vis the FDIC report (here — https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/qbp/2024mar/qbp.pdf#page=1)

The quarterly change in unrealized losses on HTM securities (+$31 billion) is equivalent to 13.2% of the commercial banks’ reported common equity as of 1Q24. That’s not a disastrous number, but this deduction is “up” from 12.0% in 4Q24.

Another way to look at it, the sector’s reported Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio would decline from the reported 13.98% to 12.14% if you deduct these unrealized losses adjust the sector’s common equity. That would be a painful punch, but not exactly mushroom clouds.

I’m not trying to say that $305 billion in unrealized losses on HTM securities is a nothing-burger, but then again it is not Armageddon for the industry as a whole… it gets a lot trickier when you start to look at individual banks though.

Then compare all this to the Q3 numbers, which were far worse. Q1 was a massive improvement over Q3. We ran some of those numbers back then.

Indeed.

I believe the sector’s aggregate unrealized losses on HTM securities were $390 billion in 3Q23. If so, that represents 17.4% of common equity for the entire sector as of Sep 2023.

The sector’s CET1 ratio would drop from 13.96% (reported) to 11.5% (adjusted).

Boys and girls. Thank you all for the great discussion today on interest rates , banks and debt. Job well done.

To illustrate the banks’ problem with their HTM assets, I recently purchased a Capital One brokered CD in the after market. It was issued in 2020 with a coupon rate of 1.45% and was priced to yield 5.3% when I bought it. Which means that when the CD matures next year, Capital One’s cost of these particular funds will over triple. Any longer term asset acquired by Capital One at the same time that my CD was originally issued will not likely generate enough interest revenue to cover the interest expense on the replacement funds for my CD.

Interesting – you can buy CDs in the secondary market?

I imagined they’d work the same as bonds – market values decline as rates rise – but I only ever see new-issue CDs in my brokers’ fixed income sections.

Yes increasing borrowing costs are a problem. But they are mitigated by rising income from their new loans having higher rates. So both sides of the ledger maintain a semblance of parity while various debts are expired and replaced. … as long as panicked depositors don’t yoink their deposits all within 1 month

Hi Wolf,

Possible typo: ‘ losses to due ‘

Best wishes from a cool and wet England!

No risk of a drought this Summer; the reservoirs in my area are brim-full…

Thanks.

Wolf,

Given that bonds have been in a 4 year bear market, and that we are in a heavily leveraged economy, when should the stock and real estate markets start to pay attention?

I know there are a lot of people with a ton of liquid assets, but I am still struggling to understand why there hasn’t been an increase in fallout yet.

Corporate earnings are accelerating. There is a belief that stock will continue to beat 5% bonds, especially given the hope for AI game changer. Isn’t it the bottom line?

True– but if you look at Buffet indicator (total US market cap divided by GDP) we are at close to 200%– playing with fire according to Buffet.

Given the valuations, if bonds stay in a bear market it will be hard for companies to issue bonds, buy stocks back, and financially engineer EPS advances. Reason being that they need to do so at higher and higher interest rates.

At some point this has to matter.

Past cycles looked sort of like this (1998 to 2000 bubble), after Long Term Capital Management was bailed out, 2 years to it mattering.

Now going on 4 years– not sure why taking so long.

Not necessarily.

Valuations can be explained by increased size of quality growth companies in the S&P 500. This is new.

5% fed rates are historically quite normal.

This Buffet indicator, like all rule-of-thumb indicators, works great until it doesn’t.

Publicly traded companies are only a portion of commerce conducted in the USA. As a thought exercise, imagine what would happen if a every private company magically went public by floating 0.01% of their equity on the NYSE.

Nothing meaninful has changed in the economy, or in the allocation of capital, and yet the “Buffet Indicator” would suddenly double overnight.

So like all arbitrary measuring sticks, it should be regarded with caution: a person needs to make a judgment call on whether any change is caused by healthy, unhealthy, or neutral trends.

(A similar example is some people insisting the DJIA will *always* dip below 2x the price of gold because in the olden days it did that a lot. Such people have been waiting 30 years for that to happen again, still expecting an 80% drop in the stock market)

What really matters is how banks fund these securities. Traditionally banks invest in assets with longer maturity and finance them with liabilities with short maturity. The original banks’ plan relied on close to zero deposit rates. Now they likely pay 4%p.a. How much do these bonds in assets yield? 3%p.a. on average? Large fixed-rate bond positions consume lots of capital as bond volatility is rather high. Also funding mismatch (long dated assets against short deposits) requires capital. Is US Treasury debt still AAA rated or not? Additional capital charge? The whole issue rather seems to be a huge capital misallocation disaster than immediate P&L problem. This is going to have huge consequences for purchases of future Treasury debt, banks will avoid T-Notes and T-Bonds exactly for lack of capital. It is much easier to place excess cash with FED and earn 5.25%p.a. and bear no risk and no capital costs. And that’s exactly what banks keep doing.

“unlike short-term Treasury bills which were yielding…sometimes below zero at the time”

How does that work? Zero coupon security that was sold at a premium to par?

Here’s your answer for auction sales at negative yields, from TreasuryDirect.gov:

Information on Negative Rates and TIPS

Treasury TIPS auction rules allow for negative real yield bids and describe how the interest (coupon) rate on the original issue would be set if the auction stops at a negative real yield. TAAPS handles negative-yield bids for all TIPS auctions, both for original auctions and reopening auctions.

In April 2011, Treasury amended paragraph (b) of 31 CFR 356.20 to state that if a Treasury note or bond auction results in a yield lower than 0.125 percent, the interest rate will be set at 1/8 of one percent with the price adjusted accordingly (i.e., at a premium). This change applies to all subsequent marketable Treasury note and bond issues: Treasury fixed-principal (also referred to as nominal) notes and bonds as well as Treasury inflation-protected notes and bonds.

https://www.treasurydirect.gov/marketable-securities/tips/tips-negative/

But I was talking about trading in the market at a negative yield.

Between Mar 2020 and Oct 2023 the 30Y rose like a rocket. For 10 years, between Dec 2008 and Nov 2018 the 30Y ranged between 4.8% and 2%.

When available for sale reached the break-even area it was sold and a little later replaced by higher rates. When the 30Y [1M] enters a recession area – when rates will drop – available for sale will be sold for profit.

Between Mar 2021 and May 2023 the 30Y-3M dropped 4% from +2.51%

to (-)1.64%. It’s in a trading range in negative territory. It might rise to 2%

==> the Fed will cut rates and the 30Y will rise. The yield curve will normalize.

The HTM scenario is not as benign as it seems. Banks holding a lot of assets that they cannot sell can create a liquidity problem, as happened with some of the regional banks. Notice how quickly the Fed jumped in and made everybody “whole”.

Another problem is that all banks, both big and small, face an interest rate hit by depositors demanding higher yields on their savings accounts. For example, I have a “Preferred Deposit” account with Bank of America that pays 5.2%. They don’t advertise it much (it is actually through Merrill but that is not really any different since BofA owns ML). If BofA is holding a ton of long-term HTM bonds paying 2%, then how can they afford to pay me 5.2%? And they may not be able to rely on investment fees bailing them out if the stock market tanks.

Ah, life is full of risks, eh? :-)