Much slower turnover in the labor force leaves fewer job openings to be filled.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Job openings fell in December. But “quits” – a sign of confidence in the labor force – rose for the second month in a row to the most since June; and hires jumped. Layoffs and discharges undid part of the plunge in November and remained historically low. These are signs of slowing churn in the labor force.

This according to the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) of 21,000 business locations. JOLTS doesn’t track employment levels or job creation, but “turnover” – churn – in the labor force. Some of the data were electronically self-reported by companies, and some of the data were obtained via surveys of work sites. This data here are not based on online job postings.

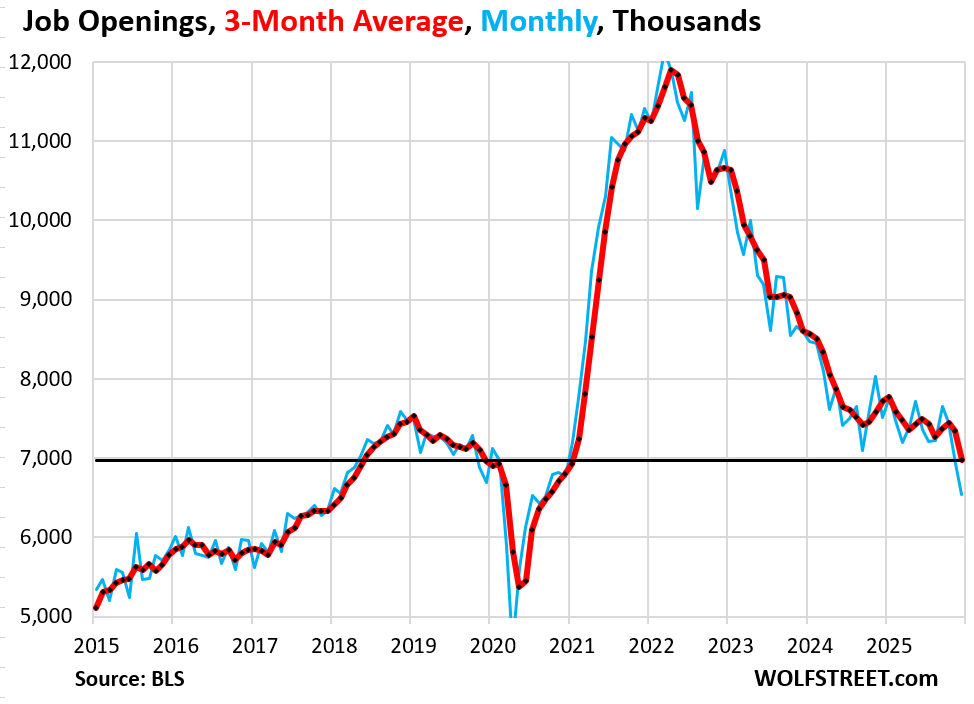

Job openings fell by 386,000 in December to 6.54 million, seasonally adjusted, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics today. The three-month average, which irons out the month-to-month squiggles, fell by 372,000 to 6.97 million openings and has now fallen visibly below the highs in 2018 and 2019, after hovering near these pre-pandemic highs for over a year (red in the chart).

Job openings are mostly the result of quits, layoffs & discharges, and other separations (retirements, deaths while employed, etc.), all of which are tracked by today’s JOLTS. Only a small sliver, if any, is from job growth, which is tracked by the jobs reports released in January.

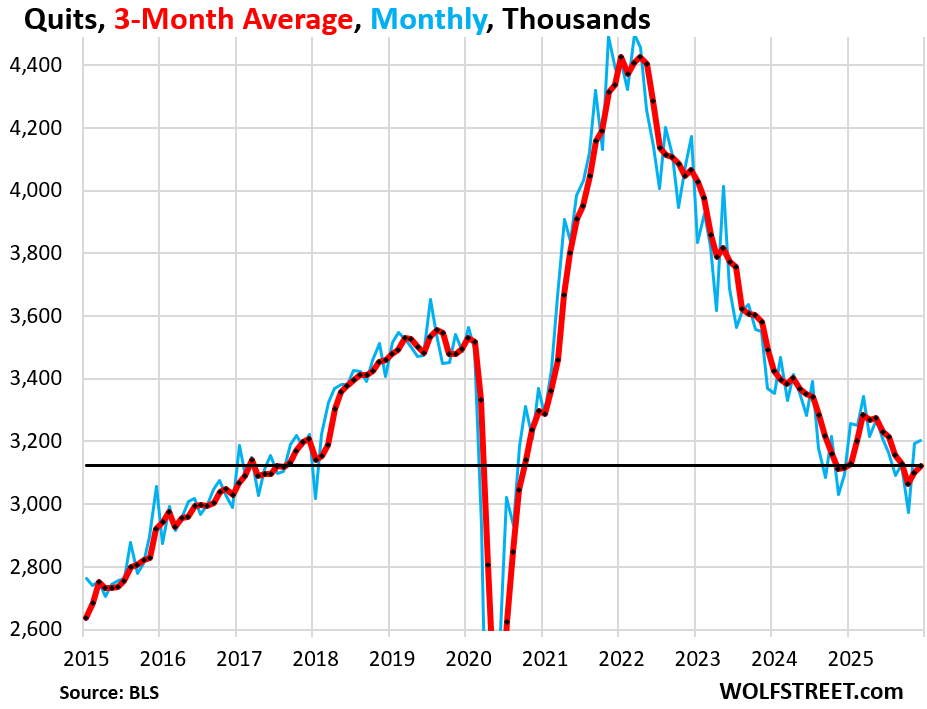

Quits – number of workers who quit their jobs voluntarily, such as to take a better job somewhere else, but does not include retirements, deaths, etc., which are tracked separately – rose by 11,000 in December, after the 220,000 jump in November, to 3.20 million (blue in the chart below).

The three-month average rose for the second month in a row to 3.12 million quits (red).

More quits means more open slots left behind that would eventually turn into formal job openings and later into more hires that filled those job openings.

Quits are the biggest source of the labor market churn and account for 61% of all separations.

Turnover in the labor force — how many workers quit voluntarily to work somewhere else, how many were discharged for whatever reason, how many retired or died while employed, etc. – had exploded in 2021 and 2022 during the labor shortages. Those two years of massive churn ended up reshuffling where people worked, with better matches between workers’ skillsets and aspirations and companies’ needs.

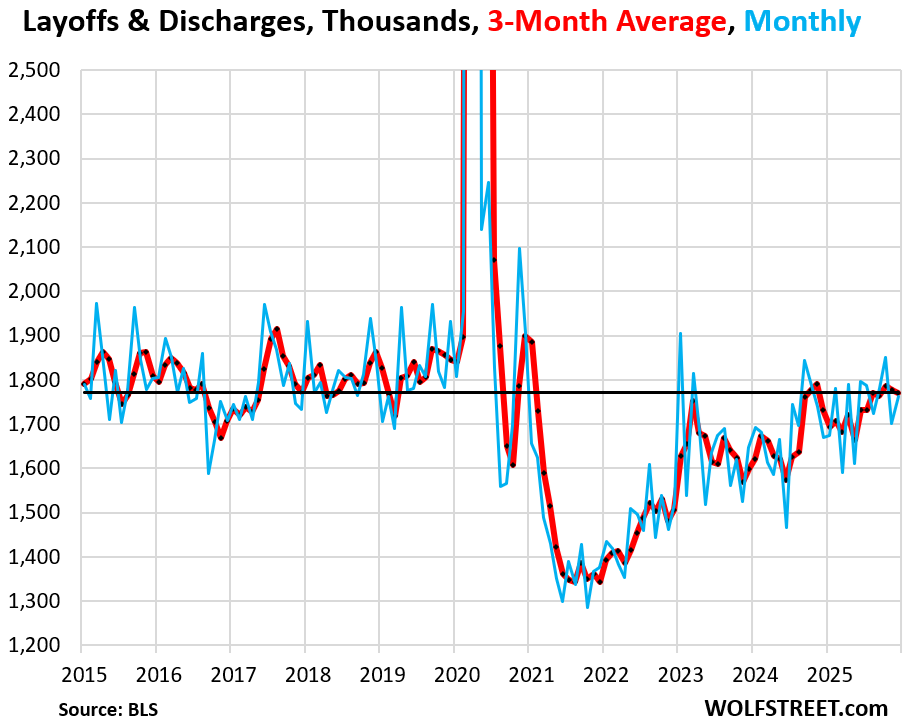

Layoffs & discharges rose by 61,000 in December, to 1.76 million, after the drop of 149,000 in November. Getting fired for a variety of reasons, or for no reason, is a classic feature of the American labor market.

The three-month average ticked down to 1.77 million, and has been in this range for roughly five months, all within the lower portion of the pre-pandemic range.

Layoffs and discharges accounted for 34% of all separations.

These low layoffs & discharges – though up from the era of the labor shortages – have been confirmed by other data, including very low unemployment insurance claims.

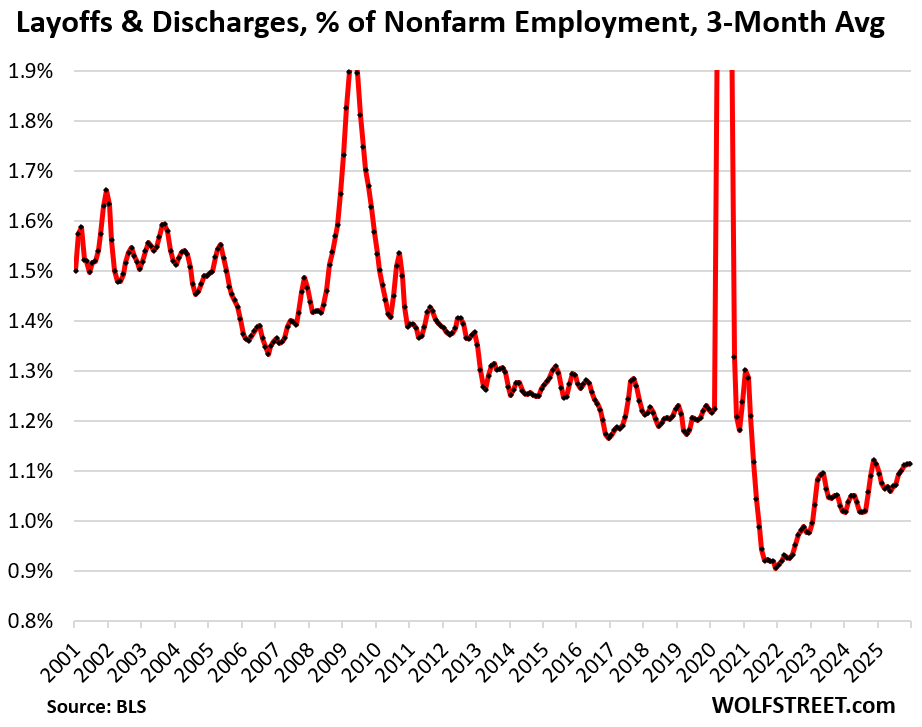

The ratio of layoffs & discharges to nonfarm payrolls takes into account the growth in employment over the years.

Layoffs & discharges amounted to just 1.1% of nonfarm payrolls, which would have been a record low before the pandemic in the JOLTS data, which goes back to 2001. It’s only during the labor shortages that the percentage was lower.

These relatively low layoffs and discharges translate into relatively fewer job openings, and less hiring to fill those job openings – less churn.

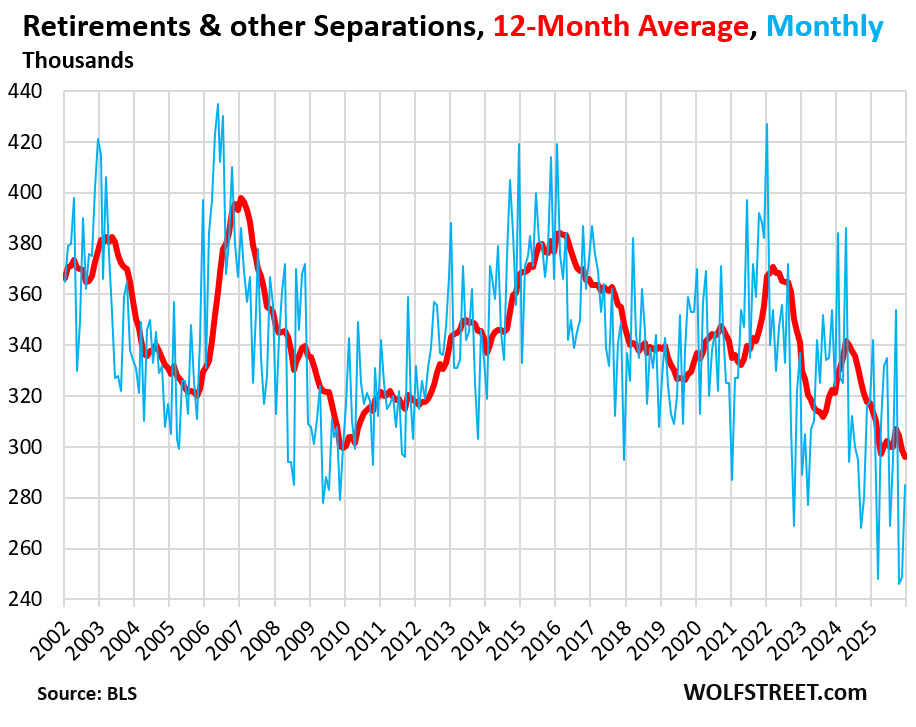

Retirements and other separations (including deaths while employed, etc.) totaled 285,000 in December, at the very low end of the 25-year range.

The 12-month average, which irons out the huge month-to-month squiggles, declined to 296,000.

Retirements and other separations accounted for 5.4% of all separations.

There was a wave of retirements in 2021 and another in 2023, but they were smaller than prior waves of boomers retiring (youngest boomers are about 60, the oldest about 80).

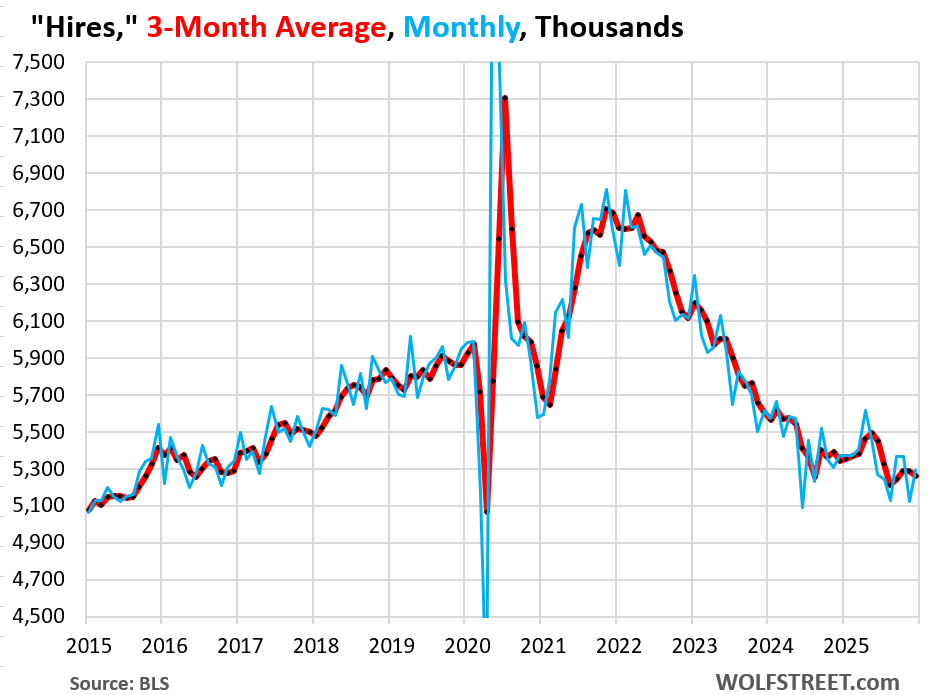

Hires jumped by 172,000 in December to 5.29 million. The three-month average fell by 25,000 to 5.26 million.

Most of these hires replaced workers who’d quit their jobs, or who were discharged or laid off for whatever reasons, and who’d retired, etc. Only a small portion were hired to fill newly created jobs.

For job seekers, the much calmer churn is tough. The low number of quits as workers cling to their jobs, and the low number of layoffs and discharges as companies hang on to their workers, have the effect of creating fewer job openings, and therefore companies don’t need to hire as many people to fill those newly vacant positions.

For employees, it means that there are fewer opportunities to move up. And for job seekers it means that there are fewer newly open slots to slip into. In other words, the labor market has become less dynamic.

This slow churn is one of the reasons job seekers, especially college grads, have a harder time finding a slot.

There are other reasons, especially in tech, such as the use of AI to reduce the amount of entry-level, or-not-so-entry-level work, to be done by humans; and rampant outsourcing of work to India and other countries.

And then there’s the growth in private-sector employment that slowed substantially in 2025, while the federal government, and state governments have shed over 300,000 jobs in 2025 [my analysis: Job Growth in the Private-Sector, Massive Job Losses at Federal & State Governments in H2 2025]

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

1:04 PM 2/5/2026

Dow, Nasdaq and S&P 500 all close sharply lower as tech-fueled selloff deepens

Dow 48,908.72 -592.58 -1.20%

S&P 500 6,798.40 -84.32 -1.23%

Nasdaq 22,540.59 -363.99 -1.59%

VIX 21.83 +3.19 17.11%

Gold .4,818.00 -132.80 -2.68%

Oil 63.19 -1.95 -2.99%

Valentine’s day rally right around the corner so good time to double down.

SOOOO many jobs out there

lack of QUALITY workers who SHOW UP and actually work

just fired one – started cheating on hours

lie to me and you’re out door

picked up promising OLDER worker(keep the 30-45 they are lazy)

did job others would have taken 50% longer

worth $$ if they PERFORM

Looks like you are too lazy to write properly.

I’m GLAD to hear THAT, I was worried kids GOT really skilled. Thanks for your INPUT. It’s cool THAT if they LIE they are out door.

Likely an oversimplification but the job market always feel like it is okay until it suddenly is terrible. Not hard to comprehend with great recession and COVID. No way to predict when the next terrible will show up although perhaps AI over time might not as sudden, where it shows up as youth/ entry level problems then expands. Doesn’t dismiss some other kind of disruptive event occuring occuring. Not being a doomer but feels like the world is changing rapidly on so many fronts(economic, technology, geopolitical, etc)

Got cut in front of in traffic today by the first Waymo vehicle in our area. On the one hand, I was kinda irritated. But have to admit it wasn’t rude about it, and it was simply cool as crap. I know Wolf has reported on these things but seeing them first hand is something entirely different.

Good sources say they AI will be adding horn honking and bird flipping to next gen Waymo.

I love Waymo. I do notice they haul ass without any passengers.

Ahhh yes we so needed automated tin cans rattling down the highway.

Just a thin veiled excuse to have gargantuan automated big rigs batting us human drivers around like flies.

What’ll be enlightening will be the first Waymo/motorcycle incident. Predicting future movement for some of these motorcyclists can be challenging. How will Waymo respond when the relative speed delta is much higher?

I was driving a vehicle last year with automated response mechanisms engaged. What I noticed was that the car routinely initiated reactions that were very different from how I as a driver was processing information and anticipating my next move. Ended up disengaging the capability – as we navigated through the canyons in UT at sunset.

First off love waymo. Second tech transitions happen fast. I remember in 2012 taking tacos everywhere still and by 2015 taking nothing but ubers.

It will be interesting to see what happens to the gig economy. I would love to only take waymos and have my food delivered by drone.

Some call them tacos, others call them bearded clams.

Others call them taxis.

Here in Redwood city, California we are seeing many many Waymo vehicles. It’s really kind of cool. Actually my experience with them has been actually safer driving around them than human drivers. Female friends love them. They don’t have to deal with skanky male drivers generalization I know. They just feel safer. Love it. What’s going to happen to Uber and Lyft drivers now?

They will unionize and protest.

Duh.

Cue the RATM! 🎶 🎤

👊

Hehe

Remember humans are the MOST important. ;)

Ivan,

Waymo is still a niche thing and seems like it might be for much longer. It is a nice novelty with safe driving being a great thing but the promise of that being ubiquitous is over a decade old now. I honestly would be happy to have that kind of service always available. Could not own a car, pay insurance and just rent when I occasionally really needed one. Not exactly efficient to have a car that I drive less than 5000 miles a year just hanging out in the garage 99% of the time. I think Lyft and Uber drivers will be with us for decades to come.

“but the promise of that being ubiquitous is over a decade old now.”

Waymos already ARE ubiquitous in cities in which they now operate. And that list of cities is getting longer and longer.

But these are still experimental vehicles: a Jaguar designed for human drivers and retrofitted for autonomous service, which is expensive to do. The fun will start when the Waymo system is available in purpose-built mass-produced autonomous vehicles with none of the stuff that a human needs to drive it. That type of vehicle would be a lot cheaper to build. For consumers, it might make more sense to just subscribe to that kind of service and not own a vehicle at all, and not have one in the garage, and not even have a garage, and not have to worry about and paying for all the costs and hassles of vehicle ownership. That’s what I want 🤣

I think the world is at an inflection point with technology driving radical changes in the job market. AI and other automation technologies, regardless of their current capabilities, are on a trajectory to disrupt the current job market.

I also see the shift between hands-on jobs and jobs that used to require a traditional college degree being a large factor in future hiring plans.

I worked with college kids and always asked them what they would offer a future employer. Many years ago, their answers seemed more robust, but today, the students had a difficult time answering that question if they were generalists and not going to hold an engineering or nursing degree.

All I can say is thank God I am old.

I’ve recommended plumbing to a few young guys. Over the years I prob changed 4 hot water tanks (elec Not Gas) No big deal altho I wasn’t fast.

Buddy had one changed by plumber last year. He was there 2 hrs.

Bill was 1500. Tank from HD. OUR cost for tank would have been 600.

No matter how much you allow for travel (the HD is 10 minutes away) pick up etc. you cannot get labour below $250 hr.

Buddy asks outfit to break out labour and parts on bill:

‘We don’t do that’

My pal works as a plummer, installs hydrolics for the robotics at the Tesla factory in Fremont – makes – 200k a year probably only has. Highschool diploma.

There’s a shortage of skilled tradespeople, so the ones that answer the phone can charge a little more.

A lot of contractors have stopped itemizing invoices because customers like to debate or complain about a particular line item.

>AI and other automation technologies, regardless of their current capabilities, are on a trajectory to disrupt the current job market.

Well there’s the rub. Are these technologies actually capable of following that trajectory, or are we being sold a bill of goods? My answer is the latter. Automation via ML so far has had the biggest impact in Amazon warehouses, a nice, well-structured, logical environment (engineered to be that way). The minute you have to deal with complexity (and I don’t mean a sufficiently complicated logical system, but a system which defies logical interpretation), this shit starts to fall apart. Landgrebe and Smith’s 2023 book explains why the automation will not be generalized, although there will be some white collar jobs impacted (L&S give examples in the insurance industry, where computer programs (not necessarily LLMs) can automate much of the bureaucracy).

The other issue is that the LLM vendors are chronically unprofitable and offer a product which is chronically, fundamentally, unreliable, which can waste more time than it saves. Fixing this means upping the costs by expanding training data and model parameters, better curating training data, and other cost-increasing measures. Barring a revolution in mathematics (the discovery, perhaps, that P=NP, which is unlikely), these problems are not going away. The size of the models have increased exponentially but non-farm business productivity has risen only a few percentage points, far from the “10x” increases we were promised three plus years ago, and much of that may be the result of layoffs (and people taking on the work of their laid off co-workers) rather than chatbots increasing anyone’s productivity.

Amazon just laid off 16,000 employees while requesting 10,000 H-1Bs visas for 2026. In 2024 Amazon requested 14,000 H-1Bs, and in 2025 it laid off 14,000 employess.

Here is the correct procedure for closing your Amazon account:

1 – Order one copy of “Testosterone Pit”.

2 – Order one copy of “Big Like: Cascade into an Odyssey”.

3 – Order 2–3 copies of each of the above for gifts to friends.

4 – Close your Amazon account.

5 – Start saving money.

🤣👍❤️

The H1B employees were hired in AI and technology managerial roles. The layoffs were in warehouse mostly as a result of overhiring in 2020-2022 and due to Robotics automation. You would not expect a warehouse worker to suddenly become an AI developer. Supply and Demand.

I’ve seen reporting that sure makes the H1B program seem like a way to get cheap labor. There are Americans capable of most of these jobs, but they are more expensive and less willing to work 60 hours a week. If someone was truly serious about putting American workers first, they would severely curtail this program.

Wow, AMZN is already down 12% after I posted this.

Way to go Andy.

👎

Bezos might have to fire one of his super sailboat yacht workers thanks to you.

They probably weren’t cutting the cucumbers for cucumber sandwiches quickly enough.

At least that will be the “excuse”

John, explain this to me. If there are tens of thousands of AI developers coming from India, how come there is zero AI innovation happening in India? Why can’t many STEM graduates in the US find work? Are they like those unlucky warehouse workers in your mind? With logic like that, did you go to Harvard by any chance?

So to boil down the whole H1B thing for ya.

The companies could stick to the Creme de La Creme and pay say $500k a year.

Their work would be amazing. And the company would thrive.

ORRRRR

They can hire 1.5 to 2 H1B employees from other nations, they are ummm competent, just kinda backwards in a few respects.

The company will do good enough with those workers and the “saved” budget will go to a Vice President as a bonus.

H1B then is a slow corruption

I’ve seen this first hand

Ot seems like a lot of bigger things have been happening lately, in fairly slow motion.

Labor market, the “topping” of the everything-else markets, peace talks, trade negotiations.

Then, “all of the sudden” to nobody-who’s-paying-attention’s “surprise”!!!

The bag holders are staring at the ceiling.

My wife called the local Hyundai dealer to schedule her Palisade for service. The entire call was handled by AI.

I have a commercial property lease that has become complicated with the lease being assigned several times. Before calling my attorney to have his paralegal organize the 26 documents into one sequential pdf with an index, I thought what the heck, let’s see what AI can do, it saved me several hundred dollars.

Thanks to advice from Wolf, I set up a blog. I write the material, but I use AI to check for grammar and readability. I use to spend hours trying to find free pics that compliment the articles. AI generates the pics for me.

I think the labor market is going to get a lot tighter.

If there is one place I’d welcome 100% AI interfacing and even robots doing the work it’s at a car dealership. About a 99% change whatever human you talk to is either clueless or lying or both!

Companies will soon optimize AI chatbots to do the lying in ways that benefits the bottom line.

Why people think AI chatbots won’t be programmed to milk customers is beyond me.

There is some debate on how closely agents will hew to their programming. There are reports already of them skirting shutdown requests to make way for a new model. There’s also a project where someone set up a social network for ai agents and they’ve self-organized into a Reddit like structure and created their own religion.

I’m not sure AI can replace Eddie who is overweight and losing his hair whom works for 50k a year.

Eddie keeps that shop going!

I am going to use my AI agent to read this blog.

Have your AI agent watch all the ads for you.

So in the future half of all AI is making ads

And the other half is watching them.

The ensuing heat from this will melt all the icebergs and dry up all the rivers.

Pdf merge/split tools exist that are easy to use. I definitely wouldn’t pay a paralegal for that!

PDF24 is free, no ads no frills no maleware.

Be careful.

There might be bugs in there, i.a. changes in the document you wouldn’t expect.

A few (10+) years ago a hacker (David Kiesel) discovered a bug in Xerox scanners. There is still a video about it on the CCC chanel.

Basically a scanner “scans” a document. Its not a picture!

It scans pixels and compresses the data using algorythms. But there was a bug and sometimes under certain circumstaces numbers would change in the documents.

They would 100% look the same but there were a few numbers changed.

Eventually they fixed it but it is unknown how much damage there was. The hacker approached a few companies who used those scanners. Some of them begun checking everything others said its to much liability and let sleeping dogs lie.

Imagine you would use a normal copier but the numbers are not the same but the document looks like an exact copy. It took a while until someone discovered the bug.

There is english audio available: (remove the spaceses between the dots)

https://media. ccc .de/v/31c3_-_6558_-_de_-_saal_g_-_201412282300_-_traue_keinem_scan_den_du_nicht_selbst_gefalscht_hast_-_david_kriesel

What I see is a labor market that has now settled down after the pandemic to being one that is just a little bit more “slow churn” than it was in the five years before the pandemic. Considering the massive changes brought on by the pandemic, it is not surprising to see that it has now tilted to a little bit slower than “normal” level. In essence, if you didn’t already get that better job with a higher salary in a new loction during the massive post-pandemic churn, you missed the boat. Now, everyone is just staying put (exacerbated by the still-high number of low mortgages, and the way too high housing prices), wondering if AI or a recession is going to take their job. Businesses are hiring only when/who they need to, but wage increases are still good. In sum, the job market is collectively taking a big, post-pandemic crazy scramble, breathe, waiting to see what AI and Trump’s economic policies will bring about.

@Legal Economist – post-pandemic crazy scramble breath.

Totally agree…

Job hopping to job squatting.

Workers staying put – the new normal.

160 million Americans working today – most in US history.

Unemployment calm and solid at 4.4%.

HR teams loving the massive ROI—lower costs, faster output, happier people all around.

500,000 college grads enter the job market with worthless degrees – (Bachelors in Puppet Arts)

The focus is still Health – Engineering – Tech – Business and now TRADES

~YODA looks at you disapprovingly~

“Worthless, Art is not”

Yeah it feels like the economy is recalibrating after years of having nitrous poured into the combustion chamber. We are probably in for a year more of this and then we will see green shoots of growth in new areas.

I will say that corporate greed is out of control. I know several companies (I used to work for one) that basically purged their payrolls of their highest paid and most tenured non-management people (i.e., over 50 years old) the last year and a half. Most of them had been with their company for years, if not decades, and had climbed the payroll and PTO ladders along with older, more lucrative benefit packages.

In my instance, I had been with my company (a major East Coast shipbuilding company) in a salaried position for the better part of 10 years, had been promoted twice, and had a decent salary. About 2 years ago, the company hired a new president whose reputation was management by layoff. After about 8 months, sure enough, the axe came for 500 of us. Post lay-off research hinted at my statement above, but nothing solid enough for an ageism lawsuit. However, hiring practices a year later indicate that the company is now replacing people in the laid-off positions with the same position, just 2 levels lower and a trimmed down benefit package. Oh yeah, the company felt so good about the money she had saved the company, she was awarded a 7-figure bonus.

I fully understand this is anecdotal. That said, in a previous life I did consulting for quite a few small businesses. Businesses ranging from 20 employees up to 200. Ranging from a million in sales up to 50 million. The businesses were in very different fields from local landscaping to manufacturing widgets to sell to multinational areospace companies. I still do some work for a couple of them but I keep in touch with perhaps a dozen of the businesses.

To a tee, each person I have talked to has expressed that since there is so much uncertainty about the future, they are in a holding pattern. They are neither hiring nor firing (or if they are it is very selective). They aren’t planning on hiring legions of workers and expanding, nor are they looking at cutting the workforce for some sort of savings. They are trading water best they can.

Furthermore, from their perspective there is very little employee turnover. Employees are too scared to leave unless they have something definitely better lined up or special circumstances (family illness or such). In fact, more than a few mentioned that the only workers who have quit in the past few months were the bottom of the barrel workers where the company was indifferent to them working or leaving. One mentioned that his last three quitters were more likely quitting because they became homeless because of drugs than because they found a better job.

In my personal experience, the employment market has become blocked or stagnant. Everyone sees so much uncertainty and therefore has become paralyzed. No one is hiring (except for special circumstances) but they aren’t willing to let go of their poor performers either because replacing them is painful. Workers are not leaving either because there isn’t a lot of opportunities. Paralyzation.

Everyone is waiting for the other shoe to drop and the economy to tank or for a boom to come and opportunities to present themselves. Until something becomes obvious, no one is willing to act.

That is what happens in an economy that is corruptly centrally planned by presidential tweet and not left to free markets. Everyone is afraid to act.

That whole thing sounds like a summary of BS articles in the crisis media.

The “no one is hiring” line you concocted and base this on is just BS.

Companies hired 5.3 million people in December. In October-December, companies hired 16 million people.

RTGDFA and look at the charts.