Central Banks diversify their holdings into dozens of smaller “non-traditional reserve currencies.”

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

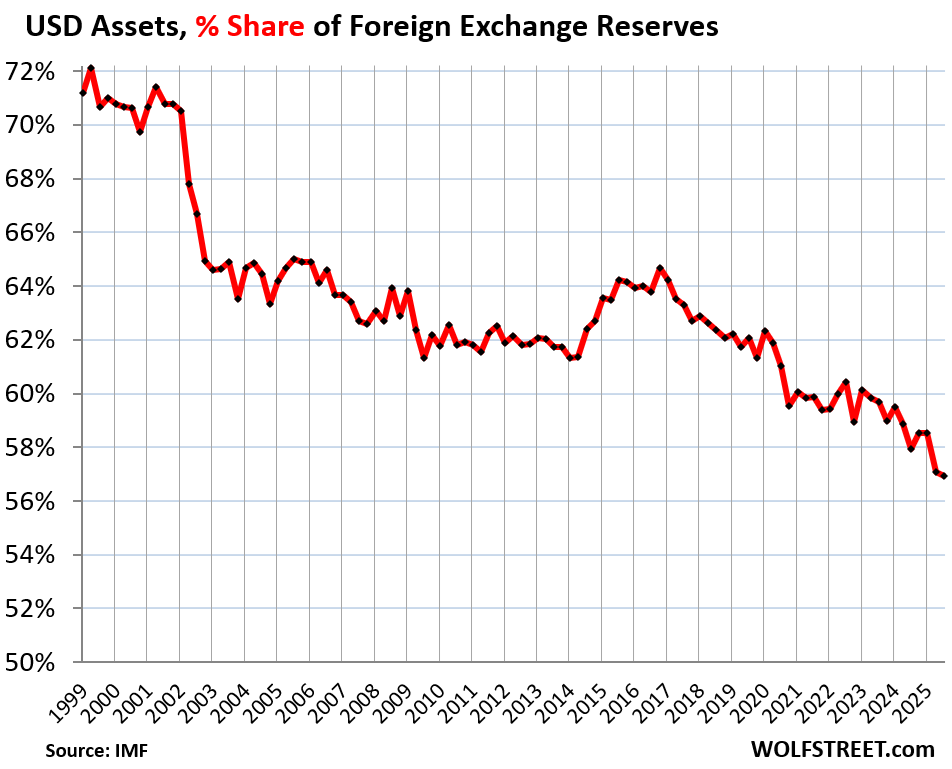

The share of USD-denominated assets held by other central banks dropped to 56.9% of total foreign exchange reserves in Q3, the lowest since 1994, from 57.1% in Q2 and 58.5% in Q1, according to the IMF’s new data on Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves.

USD-denominated foreign exchange reserves include US Treasury securities, US mortgage-backed securities (MBS), US agency securities, US corporate bonds, and other USD-denominated assets held by central banks other than the Fed.

Excluded are any central bank’s assets denominated in its own currency, such as the Fed’s Treasury securities or the ECB’s euro-denominated securities.

It’s not that foreign central banks dumped US-dollar-denominated assets, such as Treasury securities. They did not. They added a little to their holdings. But they added more assets denominated in other currencies, particularly a gaggle of smaller currencies whose combined share has surged, while central banks’ holdings of USD-denominated assets haven’t changed much for a decade, and so the percentage share of those USD assets continued to decline.

As the dollar’s share declines toward the 50% line, the dollar would still be by far the largest reserve currency, as all other currencies combined would weigh as much as the dollar. But it does have consequences.

Why is having the top reserve currency important for the US?

Foreign central banks buying USD-denominated assets, such as Treasury securities, helps push up prices and push down yields of those assets. Being the dominant reserve currency had the effect of helping the US borrow more cheaply to fund its huge twin deficits – the trade deficit and the budget deficit – and thereby has enabled the US to run those huge twin deficits for decades. At some point, this continued decline as a reserve currency, as it reduces demand for USD debt, would make the trade deficit and the budget deficit more difficult to sustain.

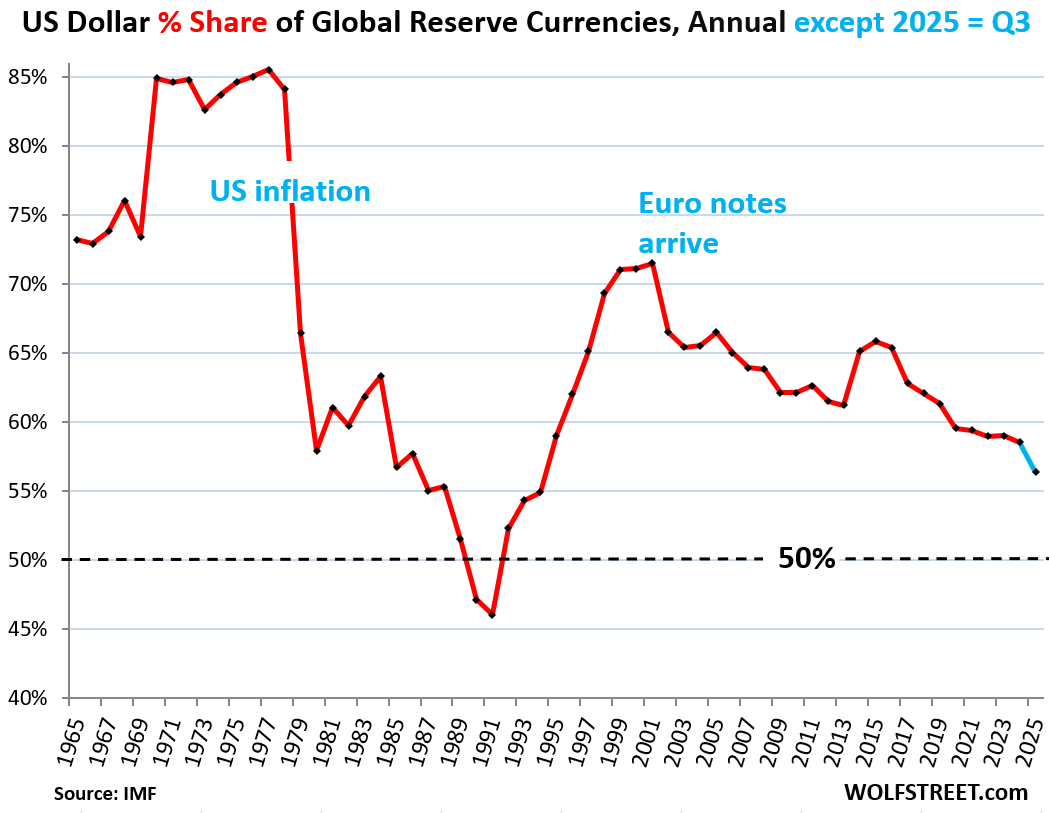

The dollar’s share had already been below 50% before, in 1990 and 1991, after a long plunge from the peak in 1977 (share of 85.5%). This plunge accompanied a deep crisis in the US with sky-high inflation and interest rates, and four recessions over those years, including the nasty double-dip recession. Central banks lost confidence in the Fed’s willingness or ability to do what it takes to get this inflation under control that had washed over the US in three ever larger waves.

The dotted line in the chart below indicates the 50%-share. The dollar’s share bottomed out at 46% in 1991, by which time the Fed had brought inflation under control, and soon, central banks began loading up on dollar-assets.

Then came the euro, which turned into the next set-back for the dollar, but not nearly as much as European politicians had promised when pushing the euro through the system; they were talking about parity with the dollar. That talk ended with the Euro Debt Crisis that began in 2009.

Then, over the past 10 years, came dozens of smaller “non-traditional reserve currencies,” as the IMF calls them.

The chart shows the dollar’s share at the end of each year, except 2025 where it shows the share in Q3:

But they didn’t actually dump USD-denominated securities.

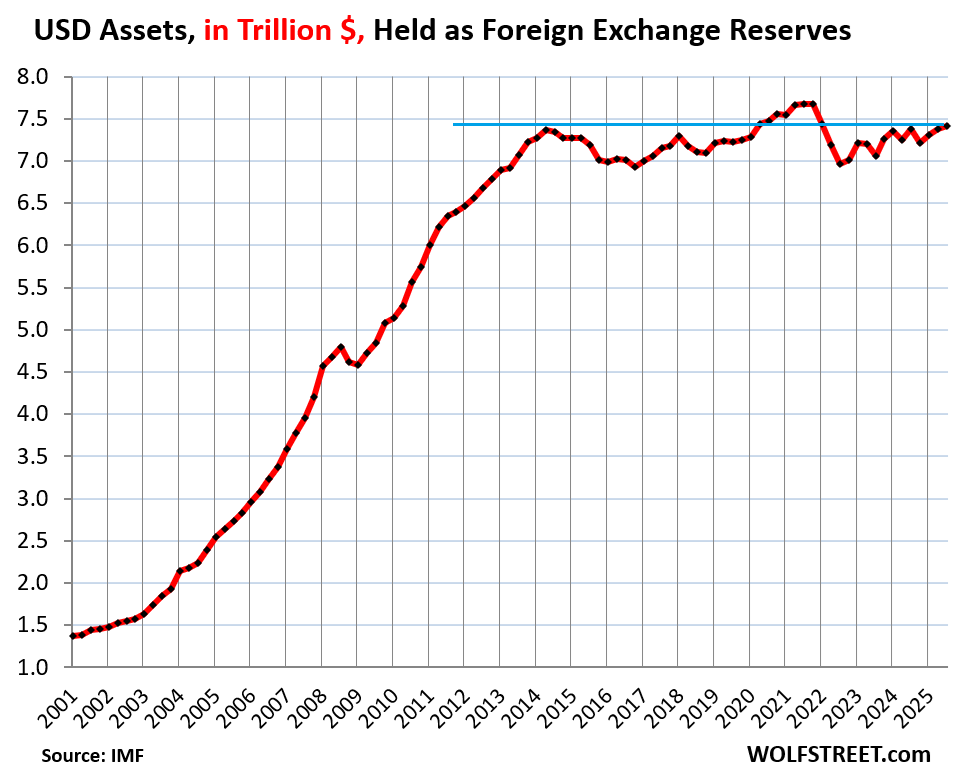

Foreign central banks increased their holdings of USD-denominated assets by a hair in Q3 to $7.4 trillion, the third increase in a row.

Since mid-2014, despite some sharp ups and downs, their holdings of USD-assets have remained essentially flat.

So, what has caused the percentage share of USD assets to decline over the years is the growth of foreign exchange reserves denominated in other currencies, particularly many smaller currencies, as central banks have been diversifying their growing pile of foreign exchange assets.

The chart below shows foreign central banks’ holdings of USD-denominated assets – US Treasury securities, US MBS, US agency securities, US corporate bonds, etc. – in trillions of dollars:

The top foreign exchange reserves by currency.

Central banks’ holdings of foreign exchange reserves in all currencies, and expressed in USD, rose to $13.0 trillion in Q3.

Top holdings, expressed in USD:

- USD assets: $7.41 trillion

- Euro assets (EUR): $2.65 trillion

- Yen assets (YEN): $0.76 trillion

- British pound assets (GBP): $0.58 trillion

- Canadian dollar assets (CAD): $0.35 trillion

- Australian dollar assets (AUD): $0.27 trillion

- Chinese renminbi (RMB) assets: $0.25 trillion

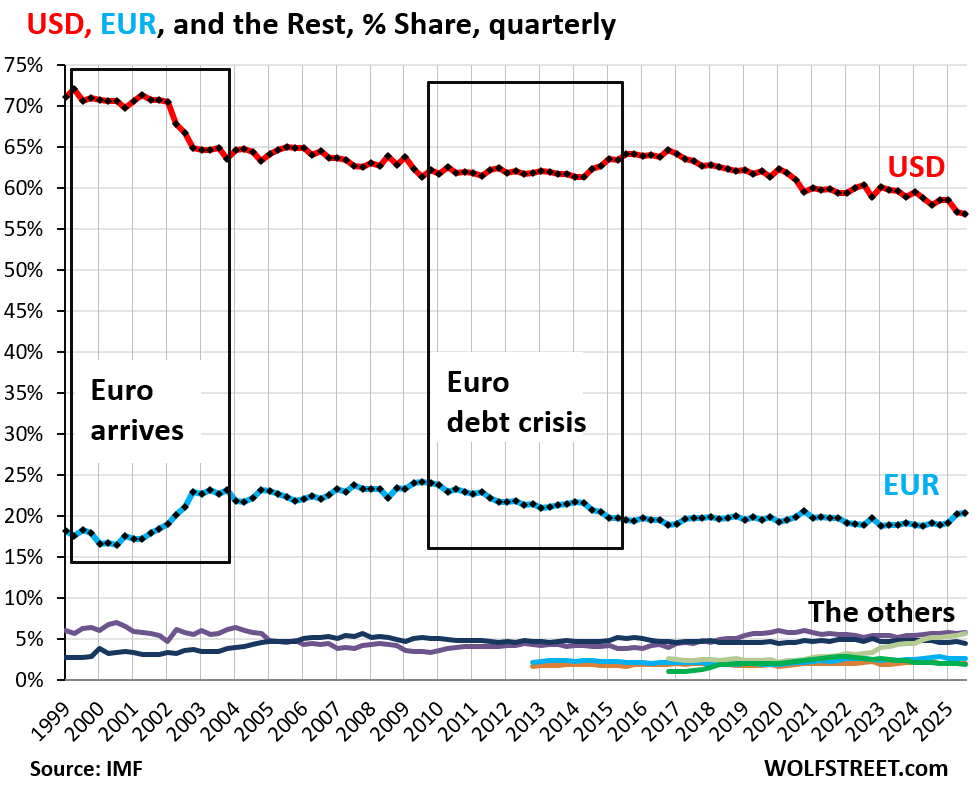

The euro’s share, #2, has been around 20% since 2015. Before the Euro Debt Crisis, it was on an upward trajectory and had already risen to nearly 25%.

The rest of the reserve currencies are the colorful spaghetti at the bottom of the chart (more in a moment). Combined, they have gained share over the years, at the expense of the dollar, while the euro’s share has remained roughly stable since 2015.

The rise of the “non-traditional” reserve currencies.

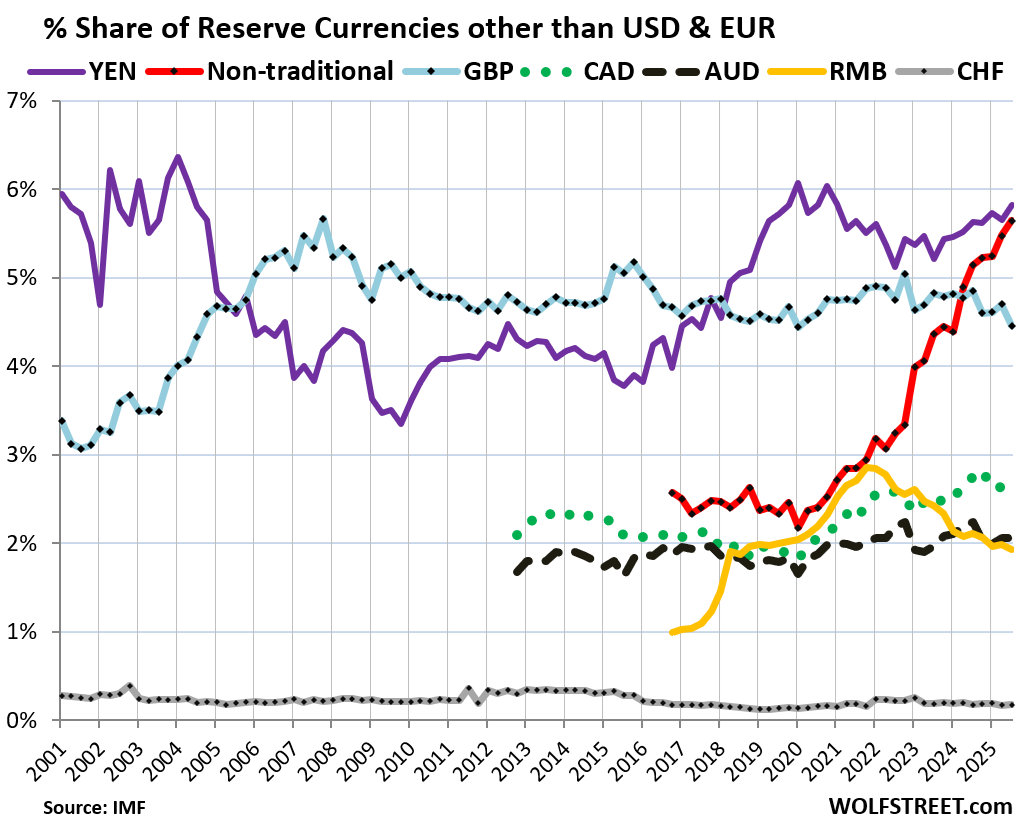

The chart below takes a magnifying glass to the colorful spaghetti at the bottom of the chart above.

The soaring red line shows the combined surge of assets denominated in dozens of smaller “nontraditional reserve currencies,” as the IMF calls them. Combined, they reached a share of 5.6%, just below the yen-denominated assets (5.8%).

But the share of the RMB (yellow) has been declining since Q1 2022, and its share is now back where it had been in 2019, amid ongoing capital controls, convertibility issues, and a slew of other issues.

In other words, the USD and the RMB both have given up share to the “non-traditional reserve currencies” as other central banks have been diversifying away from assets denominated in USD and RMB.

In case you missed my update on a slightly less ugly situation: US Government Interest Payments to Tax Receipts, Average Interest Rate on the Debt, and Debt-to-GDP Ratio in Q3 2025

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Waiting for the cliff! There is no way to stop this train. We could if we stopped using the dollar as a weapon and balanced our budget! Zero chance of that.

Would not bet on this trend to continue forever. Once word spreads on stablecoins and on how to purchase those dollars in shitty 3rd world countries using only your mobile, escaping the local depreciating currencies, the dollar will probably even strengthen in relative terms.

You’re getting things confused. “Foreign exchange reserves” — the topic of this article — are holdings exclusively by central banks and are not related to what people do with their local currencies and how they exchange them in everyday life.

IMHO – it’s surprising that this measure was lower in 1993-1994. I would have thought this measure was lowest since WWII.

MS,

It’s not surprising to me because I lived through the mid-1970s through the 1980s in college and grad school with various jobs along the way, and then starting my career. And I remember what it was like: sky-high inflation, sky-high interest rates, tens of thousands of banks and S&Ls collapsed, big repeated waves of unemployment topping out at over 10% and staying over 7% for many years. It was very hard to find a job. These were tough times for someone to start out in. The US was in a crisis. It eventually got fixed or fixed itself, and the 1990s were much better.

When other countries ran trade surplus with us they reinvested their extra USD here making the USA the world piggy back. Our US exceptionalism was the result of easy access to capital to take risk. Those trends may all be changing with current changes under way. Our military will always give us an edge in receiving capital but that may also be changing. For instance, Germany is getting self sufficient and will probably buy less US dollar denominated instruments. Tis the season for change ; Nikkei 225, peaked on December 29, 1989, hitting an all-time intraday high of around 38,957.44. It took until Feb 22 2024 to regain that high.

DXY is in a trading range since July 1st low @96.4. When trillions of foreign promises actually pour in the dollar will rise. If SPX turns down DXY will rise. The dollar might fall only if we lose a major war.

I agree with you, DXY 50DMA is 99.13 above its 200 DMA of 99.06. Everything is interconnected and it’s all setting up for the perfect storm. If DXY gets above 102 it’s a good time to diversify 105 would be an overshoot of the 104 target. I like the traditional commodity currency, Canada kiwi and Australia, Norway. When or if the DXY reaches those levels I would be a buyer of commodities currency or their short term bonds. The USD or DXY looks like a safe place to be and of course the Yen, but the yen has implied risk if central banks other than Japan make a coordinated action to prevent the Yen from appreciating as a PUT to global risk selling. Our Inflation should rise and unemployment should fall. Government Puts will be sly. If the $2000 stimuli check get issued in 26 will 9 million defaulted student loan people make a 2k payment? Probably not. :) but they should!

Those 9 million people would be wiser to spend $2k on increasing their skills and employability (especially learning how to work with AI and build workflows) so they can increase their earning power and pay back their loans.

Interesting article! Wolf, what happens to the graphs when the vertical axis is in Euros?

1. The euro didn’t exist before 1999. The long-term chart (chart #2) goes back to 1965.

2. The US dollar is still the refence currency, and so all global things, when expressed in a common currency, are expressed in US dollars. So you can get the GDP of Japan in YEN and in USD, but not in EUR. Get used to it.

Hello Wolf, thank you for producing this series on reserve currencies. I was wondering if you had any more detail on the specific currencies within “non-traditional reserve currencies?”

Anecdotally, I have heard that the Qatari Riyal has begun to play a significant role across West Asia and East Africa in terms of exchange, though I do not know if that would have any bearing on what currencies central governments keep in their reserves.

The IMF does not disclose detailed data on the dozens of currencies in the “non-traditional” category. The Chinese RMB was part of that basket until the IMF pulled it out in 2016 and gave it its own category that we can see now.

Note that the share of these dozens of currencies combined is 5.6%, so each currency alone has a minuscule share, but all combined, they account for 5.6%. If you add the RMB back into this group, the percentage rises to 7.6%. So as a group, it would be #3, but spread over dozens of countries.

The non-traditional currencies group was composed in part by the currencies of other OECD countries, according to an IMF article in 2022 (it didn’t give per-currency share and details either).

So looking at the OECD countries whose currencies are not broken out separately here, that would be the European countries that are not part of the Eurozone (Czechia, Denmark, Hungary, Iceland, Norway, Poland, Sweden), Mexico, Costa Rica, Chile, Colombia, Turkey, Israel, South Korea, and New Zealand.

The other part of the currencies was often based on trade relationships and currency pegs. Here is a quote from the article:

“For example, Namibia holds a large share of its reserves in South African rand due to its peg to that currency and trade relations with South Africa. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyz Republic hold Russian rubles due to their close trade relationships with Russia.”

Thank you for the explanation. I do wish the IMF would provide more detail on the smaller currencies. The quote you pulled out at the end is suggestive, and I am tempted to use it to spin a narrative about the rise of bilateral trade settlement in local currencies at the expense of USD.

Either way, it will be interesting to see whether these trends hold through the latter half of the decade.

1. Bilateral trade agreements have existed long before the big ones were negotiated. Neighboring countries always had trade agreements. But trade agreements are about tariffs and various customers regulations, not currencies. Trade agreements don’t dictate currencies. Companies that trade with each other can use whatever currencies they agree to use. And they have always traded in their local currencies, nothing to do with the USD.

2. The USD has never been used in trade between Namibia and South Africa. Or really anywhere in Africa. They use regional currencies, such as the West African CFA franc and Central African CFA franc. Or they use local currencies.

3. What’s relatively new are these huge global trade agreements, but even these huge global trade agreements don’t specify which currency has to be used.

4. Companies can pay for any purchase with any currency as long as the seller agrees to take it. This is part of the sales contract. If an African mining company sells minerals to a a company in the US, it’s going to gladly get paid in USD. If it sells it to a company in Germany, it’s going to gladly get paid in EUR.

5. Trading in USD is very different from “reserve currency” and has no impact on the USD. It doesn’t make any difference to the US whether a German company pays in EUR or USD for LNG from Qatar.

Why did you exclude gold?

This is just tiring.

1. Gold is NOT a currency and therefor not a foreign exchange asset.

2. This article is about “foreign exchange CURRENCIES” that central banks hold.

3. Gold does not figure into any of these numbers since it’s not a a currency and not a foreign exchange asset.

4. Gold is a “reserve asset,” and so you might want to see the share of gold as a percent of total “reserve assets.” But that’s a separate topic and has zero business being here.

No mention of Gold? Is that included in the redline of “non-traditional reserve currencies”

This is just tiring.

1. Gold is NOT a currency and therefor not a foreign exchange asset.

2. This article is about “foreign exchange CURRENCIES” that central banks hold.

3. Gold does not figure into any of these numbers since it’s not a a currency and not a foreign exchange asset.

4. Gold is a “reserve asset,” and so you might want to see the share of gold as a percent of total “reserve assets.” But that’s a separate topic and has zero business being here.

Gold leads to madness!

So shiny!

Haha

It looks like dollar holdings are just fine……but in reality…..the purchasing power of dollars held by the banks since 2014 have declined by 37%.

Since the banks want to hold approximately the same percent of total gdp they have added other currencies to make up for the dollar.

So what looks stable is actually a huge drop in dollar holdings not only as a percent but more importantly how much it buys……which will continue as long as the deficits do…….good luck with that.