Update on a slightly less ugly situation.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

[The only and possibly dubious benefit of having delayed the release of the Q3 National Accounts, including GDP, till December 23 is that we get to discuss the US fiscal mess in terms of tax receipts and GDP on Christmas Eve! And the situation looks a little less grim. Merry Christmas everyone!]

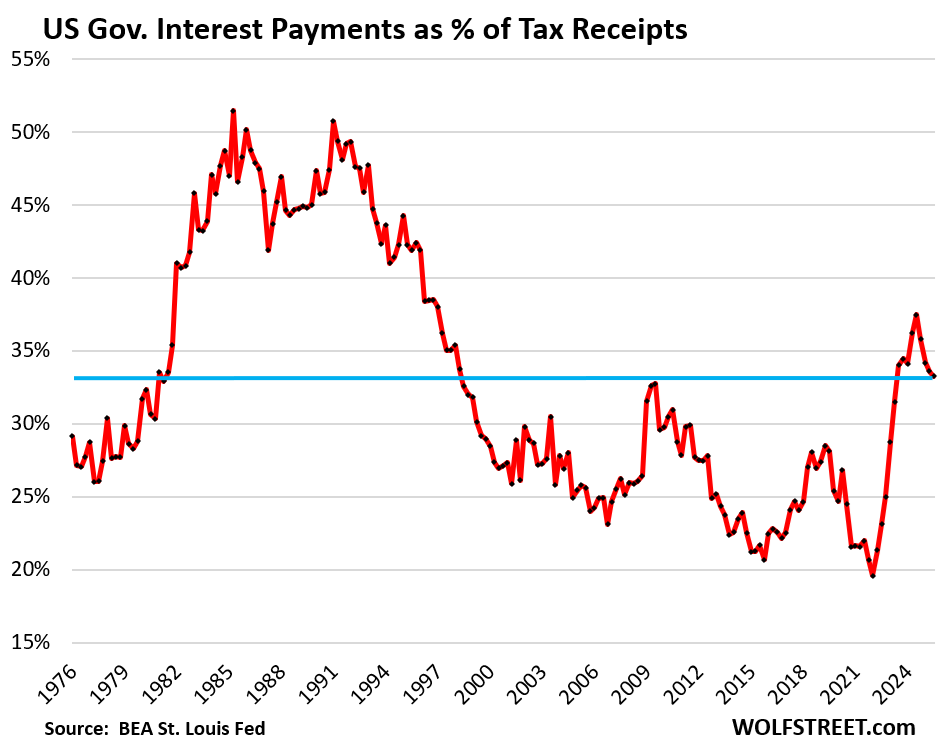

A crucial issue of the US government fiscal situation: What portion of tax receipts are eaten up by interest payments on the monstrous federal debt?

At the peak of the last fiscal crisis in the early 1980s, the ratio of interest-payments to tax receipts had exceeded a hair-raising 50%. It was a crisis because the 10-year Treasury yield was over 10% for six years in a row and went over 15% for a time; and the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate was over 10% for 12 years in a row and went over 18% for a time.

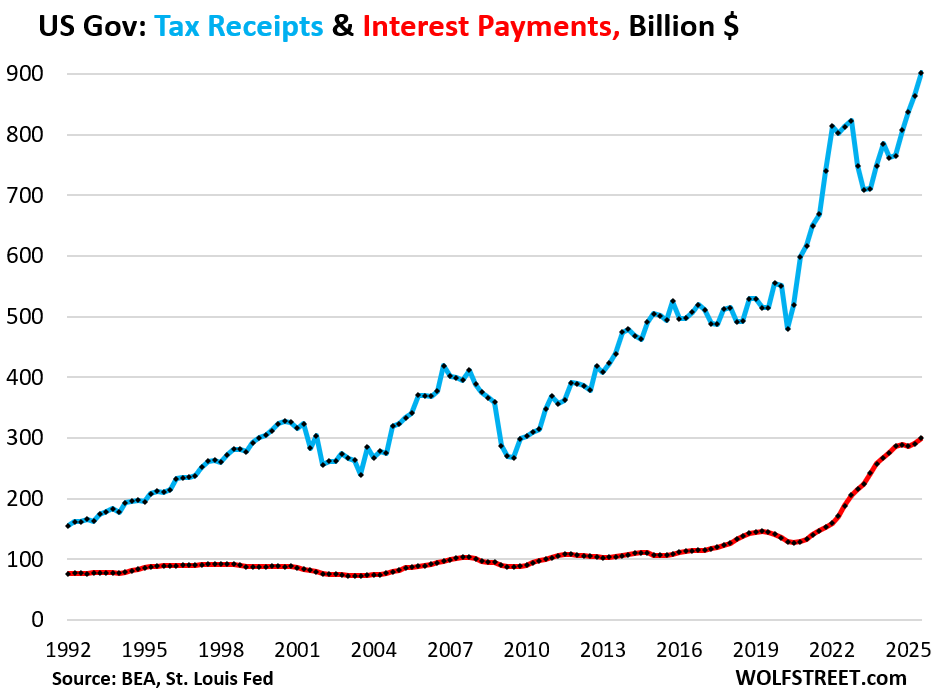

Tax receipts by the federal government jumped by $38 billion (+4.4%) in Q3 from Q2 and by $137 billion (+17.9%) year-over-year, to a record $902 billion. This includes $87 billion from net tariffs in Q3 (blue line in the chart below).

A growing economy generates more taxable income and higher tax receipts. Growing asset prices generate capital-gains taxes, but they’re very volatile. The year 2022 was lousy for stocks, and so tax receipts in Q1 and Q2 2023, when capital gains taxes for 2022 were paid, fell from the spike during the free-money pandemic years. And most of the tariff revenue is new, starting in Q2.

Interest payments by the federal government on its monstrous Treasury debt rose by $10 billion (+3.3%) in Q3 from Q2, to $300 billion (red in the chart below).

Interest payments don’t occur in a vacuum. They occur in the context of tax receipts – what’s there to pay for them.

This measure of tax receipts was released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis as part of its Q3 National Accounts data yesterday. It tracks the tax receipts that are available to pay for general budget expenditures, such as defense spending, interest payments, etc. Excluded are receipts that are not available to pay for general budget expenditures and are not included in the general budget, primarily Social Security and disability contributions that go into Trust Funds, out of which the benefits are then paid directly to the beneficiaries of the systems.

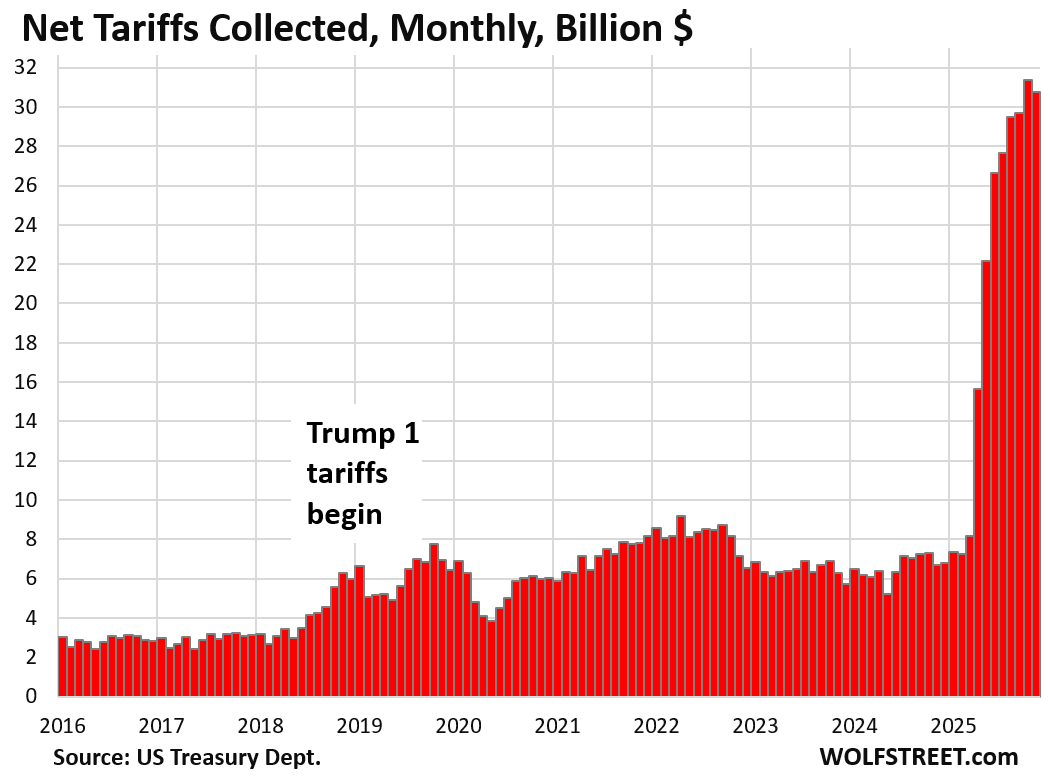

Tariffs are now a substantial contributor to tax revenues. In Q3, they added $87 billion to the tax receipts ($902 billion) that were available to pay for the interest expense and other general-budget expenses (chart through November, data via Monthly Treasury Statement):

Interest payments as a percent of tax receipts: Interest payments in Q3 ate up 33.2% of the tax receipts available to pay for them.

The ratio declined for the fourth consecutive quarter, driven down by the increase in tax receipts that outran the increase in interest payments.

The ratio was also helped by the average interest rate on the debt, which has remained roughly unchanged since mid-2024 – after surging in 2022 through early 2024 with the Fed’s rate hikes (Treasury bill rates) and QT (rates on long-term Treasury securities). More in a moment.

The recent high of the ratio occurred in Q3 2024, at 37.5%, which had been the worst ratio since 1996, when the ratio was already on the downtrend from the crisis times in the 1980s.

The magnitude and speed of this spike from the low point in Q1 2022 to Q3 2024 was unprecedented in modern US history:

The average interest rate on the Treasury debt — now much higher than the historic low at the beginning of 2022 of 1.58% — has stabilized since mid-2024, and in November was 3.35%, same as in July, according to Treasury Department data.

New interest rates enter the interest expense when old Treasury securities mature and are replaced with new securities at the new interest rate, and when additional Treasury securities are issued to fund the deficits.

The $6.7 trillion in Treasury bills (terms between 1 month and 12 months) are constantly getting rolled over as they mature. T-bill interest rates, as sold at auction, track the Fed’s expected policy rates. As the Fed cut its policy rates, the interest rate that the government paid to sell new T-bills fell – lower interest costs for the government, and lower yields for investors.

But longer-term securities by definition are slow to cycle out of the debt, so changes in long-term interest rates filter only slowly into the debt as old maturing debt is replaced with new debt that comes with the new interest rates.

The interest rates at which the government can sell long-term Treasury securities have lurched up and down over the past three years, but within a range.

For example, over those three years, 10-year Treasury notes were sold at auction with yields from 3.3% and 4.6%. At the most recent 10-year note auction on December 9, the yield was 4.175%, in the middle of that range.

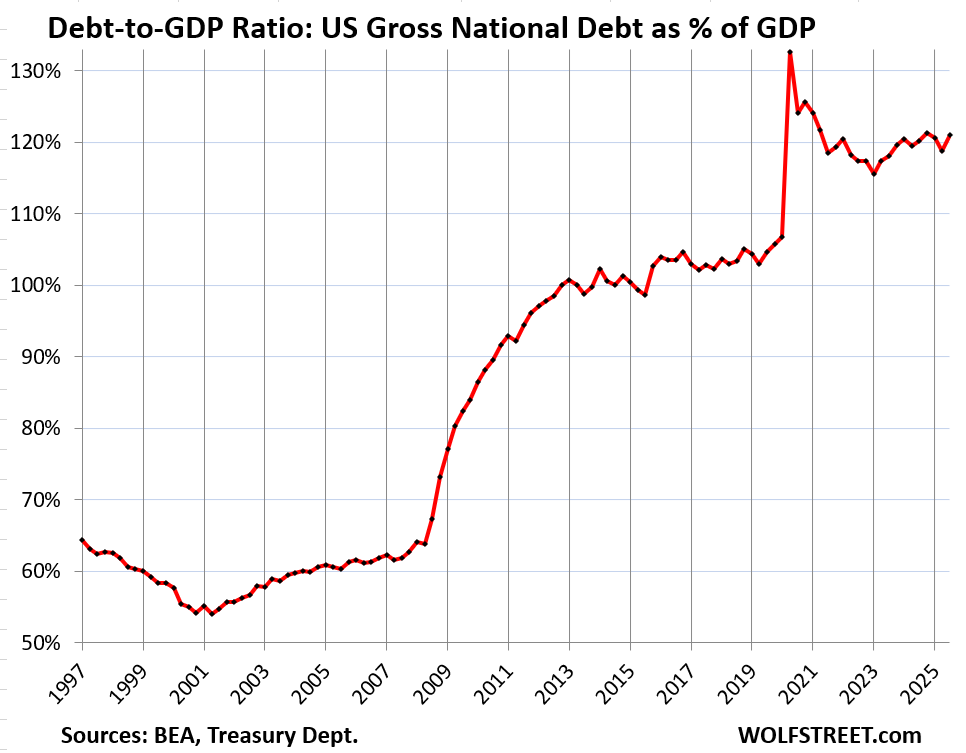

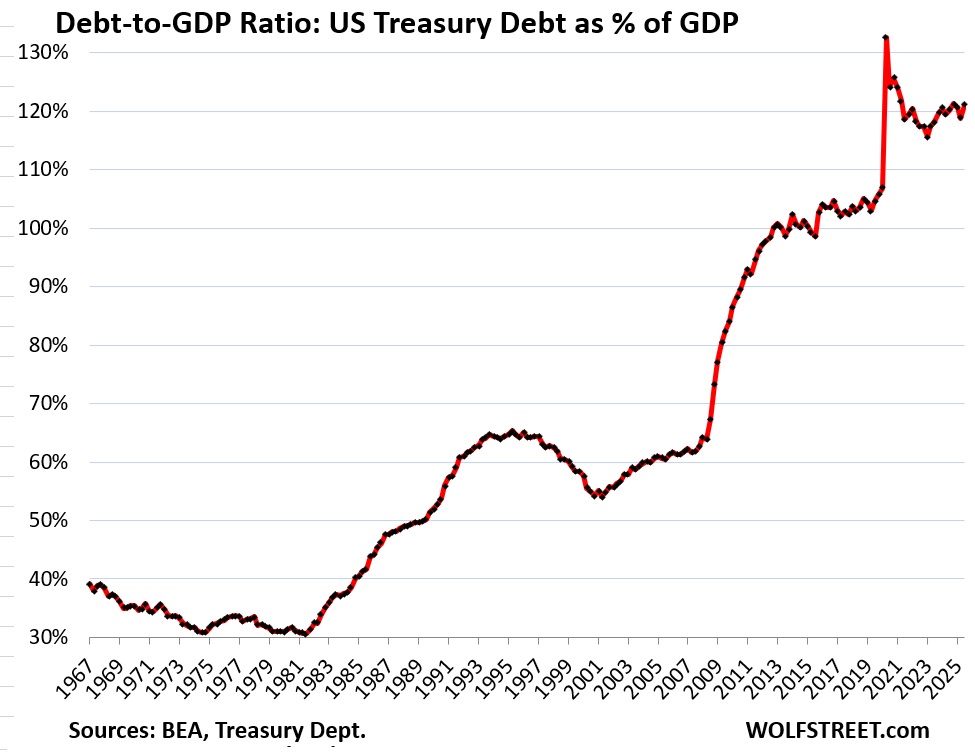

The ugly Debt-to-GDP ratio: Total Treasury debt at the end of Q3 was $37.6 trillion – though it’s now already $38.4 trillion. Nominal GDP in Q3 jumped to $31.1 trillion annual rate, as per the GDP data yesterday (WHOOSH, Went the Economy in Q3. The Fed Needs to Watch Out, Economy Is Running Hot).

So the debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 121.0% in Q3. But the ratio for Q1 and Q2 had been held down by the effects of the debt ceiling, which prevented the debt from ballooning. In Q3, after the debt ceiling was raised in early July, the debt made up for it and spiked.

But the debt-to-GDP ratio was down a hair from Q4 2024 (121.3%).

The Debt-to-GDP ratio = total debt (not adjusted for inflation) divided by nominal GDP (not adjusted for inflation). Inflation cancels out because the inflation factor affects both the numerator and the denominator equally.

The long-term view is troubling. Each crisis causes the debt-to-GDP ratio to explode. But the recession in the early 2000s started a new trend: exploding the debt-to-GDP ratio without ever bringing it back down, not even a little bit, afterwards. It just kept rising until the next crisis, when it exploded again.

The lockdown during the pandemic was unique in that GDP collapsed and the debt exploded and the ratio when straight up in Q2 2020. As the economy reopened, and GDP bounced off, while the growth of the debt slowed somewhat to still very high growth rates, the ratio backed off but has remained in nosebleed territory.

Once upon a time, the debt-to-GDP ratio was below 40%:

A default on this debt is not in the cards. The US, by controlling its own currency, cannot default on debt issued in its own currency because it can always “print” itself out of trouble (Fed buys some of the debt).

But in an inflationary environment, printing money to service an out-of-control debt and deficit could cause inflation to spiral out of control, wreak havoc on the economy, and lead to years of wealth destruction and lower standards of living. Everyone knows this.

So the top option on the official wish list seems to be to trim the annual deficits a little – including through tariffs – to where economic growth (as per nominal GDP) and modest inflation (3%-5%) outrun the growth of the debt, which would gradually over the years whittle away at the problem. This wish list item assumes that no recession and no other crisis blow this scenario apart.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays everyone!!!

Merry Christmas Wolf and thanks for the interesting charts as always. I promise I read the article too!

Marry Christmas from a warm Saipan!

Don’t even think a crisis is needed, just the continued rollout of AI. I’m not anti-AI, just anti not doing anything at the government level to address the implications. That said, there is no slowing it down, partly because it is the current economic catalyst and also that just not how we roll.

What could gov’t do about AI ?

They are attempting to monopolize it, with little success, with initiatives like restricting critical hardware such as graphics chips to China.

However I feel that all this is really doing is to push China into spinning up indigenous production of said hardware.

Merry Christmas Wolf!

What could gov’t do ?

How do the CPI-driven principal adjustments to TIPS and I-Bonds enter into the computation of interest paid? Are the daily (for TIPS) or monthly (for I-Bonds) principal adjustments treated as (non-cash) interest payments, or are the cash payments of those principal adjustments only treated as payments of interest at the maturity (or redemption) dates?

Government accounting is cash based. So I would think that the inflation protection that is added to the principal is accounted for as an interest expense in the budget when it is paid at maturity of the TIPS.

Since TIPS have been around for many years, there are several issues that mature each year, and when they mature, that inflation protection would be added to the interest expense.

TIPS balances are small, now $2.1 trillion, about 5.5% of the total debt.

Same with I-bonds. But they don’t mature. They’re redeemed by the holder (sold back to the government) when the holder wants to. After 30 years they stop accruing interest. But the holder has to actually redeem them to get their money back. It’s not automatic.

I-bonds and EE savings bonds are minuscule, about $150 billion in total, so they don’t matter at all.

Merry christmas and happy holidays to everyone.

May our investments all turn green.

Shorts mature in time.

(Engels will get sober soon)

The girl will talk to us in tomorrow…

I wish wolfstreet will become the main street…

Thanks for the wonderful 2025

Merry Christmas Wolf!

You probably don’t cover this topic but I am interested to find out impact of BRICS accumulating massive amounts of gold reserves to reduce dependency on dollar. It will be great if you weigh in your expertise and what BRICs is trying to accomplish and what if they will be successful.

Look at 20-year charts of the BRICS currencies. They (except for the RMB, the C) have plunged or collapsed against the hated USD.

Merry Christmas Wolf

Thank you very much for your remarkable insights this year. Hope you get some downtime.

Take care and best regards.

For all the publicity and whining, tariffs according to Mr. Wolf are only about 10% of revenue. Inflation of 3% on 38 trillion of debt brings in 95 billion a month or about 10% as well. Boosting tariffs to 20% and squeezing in another 50 basis points of inflation would give about 33% of the budget. From this it looks like the budget deficits are overrated.

Thank you Wolf for a great year of reporting. All looked pretty good, higher GDP,higher tax receipts, and then….121% ratio!! Wow..the US has been on a spending spree for years, maybe decades. Without budgetary discipline we are in for a world of hurt. We the folks need to wake up.Having just retired, this gives me the jitters. Anyway, everyone have a Merry Christmas!

Merry Christmas Wolf and all, Feliz Navidad!

> and modest inflation (3%-5%) outrun the growth of the debt

So how’s this going to work in practice for the existing debt that will be rotated? If they let inflation run at 5%, what’s that going to do to the yield of newly issued long-duration bonds? Should be considerably higher yield if the bond market is functional.

They can switch to issuing mostly short duration treasuries. What are those going to be at when inflation is 5%? What happens if inflation blows out for a period to 8%+ because inflation is more volatile at higher % levels. Sitting in mostly short duration will add significant volatility to interest payments since those rotate quickly.

Don’t see how higher inflation helps reduce interest payment costs mid-term, especially with the existing debt level and the still relatively low average interest rate of 3.5%.

Real GDP and higher income growth per year sure helps. Inflation strategy doesn’t add up unless the plan is to control the full curve and screw over bond holders. Or fudge inflation numbers indefinitely.