Bond market reacts to inflation expectations and supply of new bonds, not the Fed’s policy rates.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

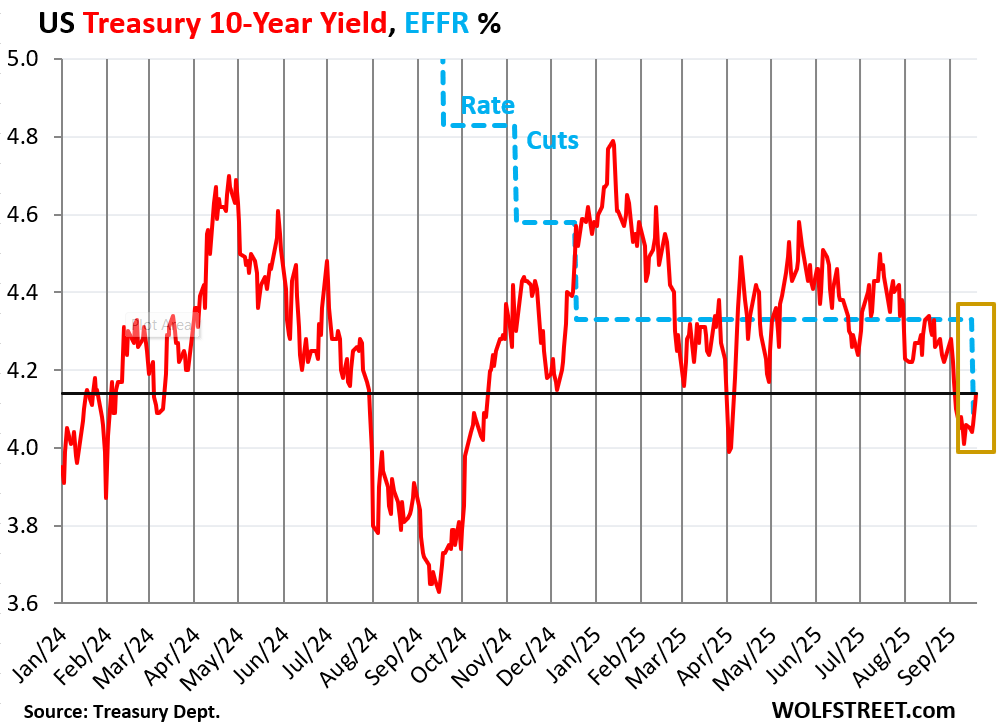

The 10-year Treasury yield closed at 4.14% on Friday, after having dropped briefly below 4.0% on September 11 (closing at 4.01%). On Wednesday last week, during an algo-driven moment, it also dropped to 4.0%, from 4.05%, then jumped right back to 4.05%, and ended the day at 4.06%, after the Fed had released its statement of a 25-basis-point cut. It then continued to rise to end the week at 4.14%.

The Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR), which the Fed targets with its five monetary policy rates, dropped by 25 basis points to 4.08% after the cut, from 4.33% before the cut (blue in the chart). The EFFR is now once again below the 10-year Treasury yield.

This phenomenon of rate cuts causing long-term yields to rise is rare – but we had it before, namely a year ago, when the Fed cut by 50 basis points at its September meeting, and the bond market got spooked by the sight of a lax Fed amid accelerating inflation. By the end of the year, the Fed had cut by 100 basis points, and the 10-year Treasury yield had jumped by 100 basis points, and the Fed, having learned a lesson, put further rate cuts on ice, and started talking hawkish, which succeeded in coaxing long-term yields – including mortgage rates – back down. But then the Fed went at it again with another rate cut.

This time, the Fed was more careful, less dovish: It cut only by 25 basis points, and Powell was less dovish than the statement even, and so the bond market’s reaction to the rate cut might have been a little less pronounced than it was a year ago.

But if the next few batches of inflation data continue along the worsening inflation trends, it could still spook the bond market further and lead to higher long-term yields despite the rate cuts.

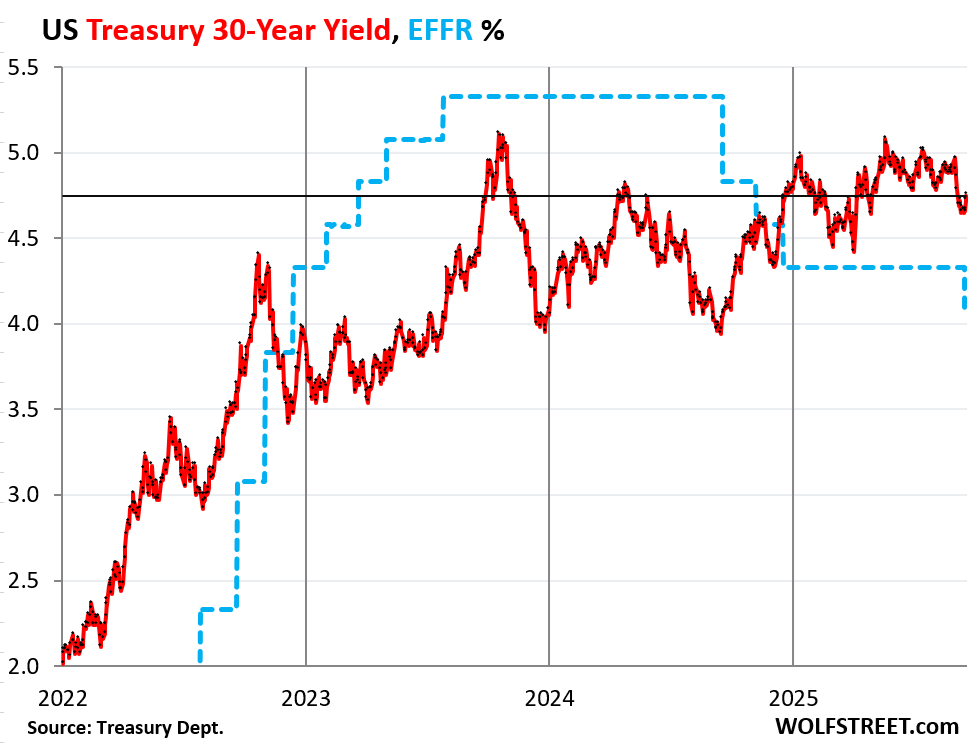

The 30-year Treasury yield ended the week at 4.75%, up by 10 basis points from the day before the Fed’s rate cut.

The upward trend of the 30-year yield started in August 2020 at 1.25% (after trading briefly at 1.0% in March 2020). By the end of 2021, it was at 2.0%, and by the end of 2023, just under 4%. It went over 5% in October 2023 and a few times briefly since then.

Note the divergence of the 30-year Treasury yield and the EFFR, as the 30-year yield reacts to bond-market issues, such as expectations of future inflation and supply of new bonds that have to be absorbed, rather than the Fed’s policy rates.

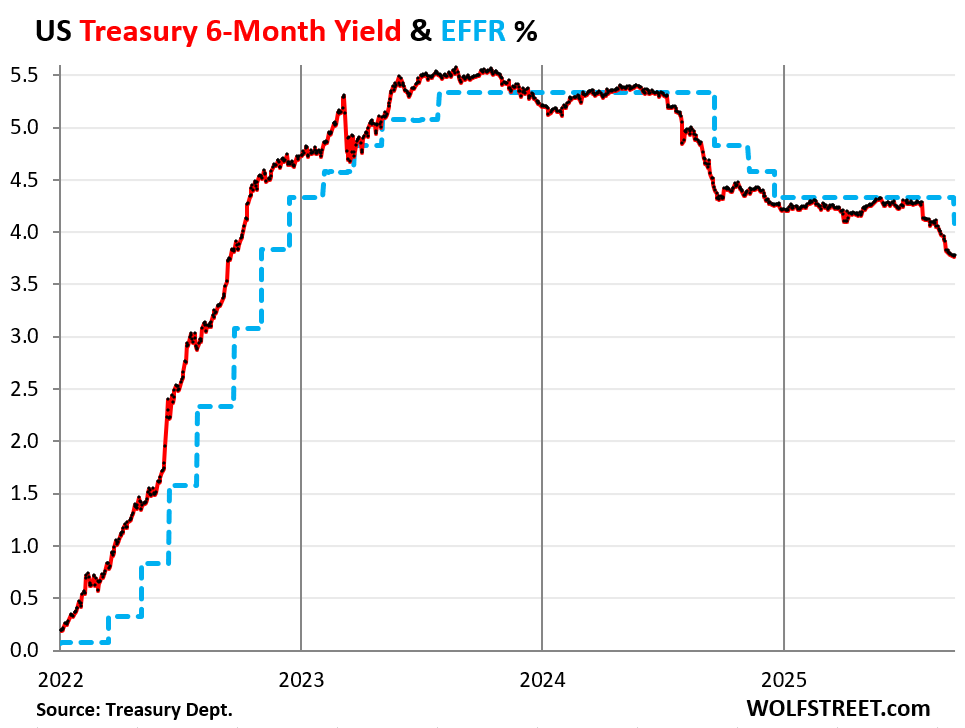

But the 6-month Treasury yield reacts to expectations of the Fed’s policy rates over the next two months or so and is a good indicator where the short end of the bond market thinks the Fed’s policy rates will be within its window. It currently expects another 25-basis-point cut over the next two months.

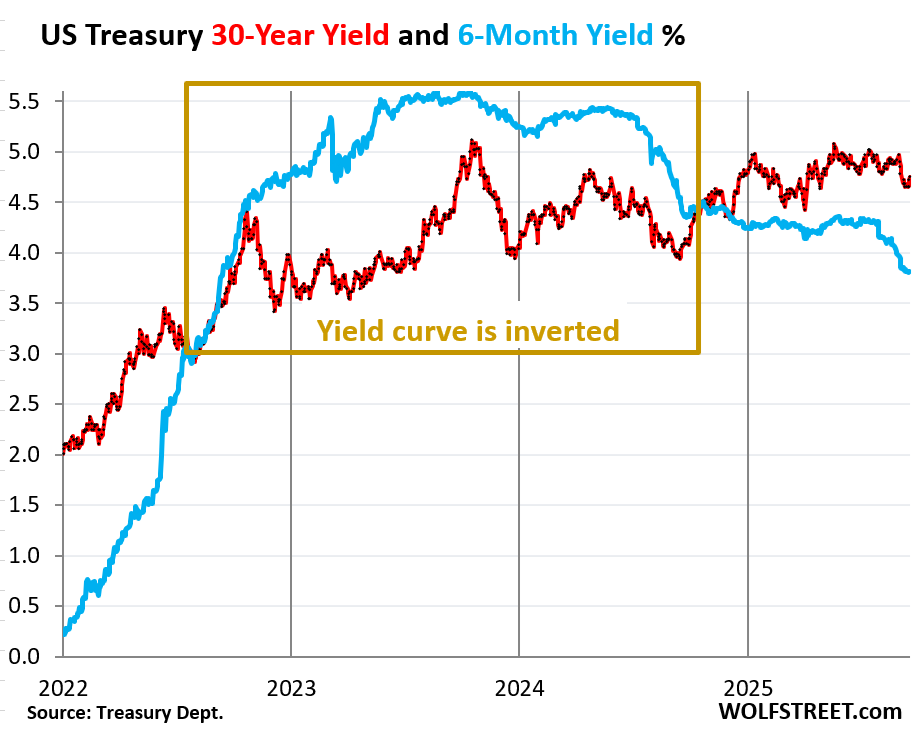

So the 30-year Treasury yield – which reacts to the bond-market issues of inflation expectations, supply of new bonds, etc. – has diverged dramatically from the six-month Treasury yield, which reacts to expectations of the Fed’s policy rates over the next two months.

That part of the yield curve – the 30-year yield and the 6-month yield – inverted in mid-2022 as the Fed was pushing up policy rates in 75-basis-point increments, and the 6-month yield stayed ahead of them, while the 30-year yield was only slowly disabusing itself from the Fed’s concept that this inflation was transitory.

But as the Fed was cutting rates in late 2024, the 6-month yield stayed ahead of those rate cuts and fell, while the 30-year yield surged, driven by an edgy bond market, and that part of the yield curve un-inverted in October 2024 and has steepened since then.

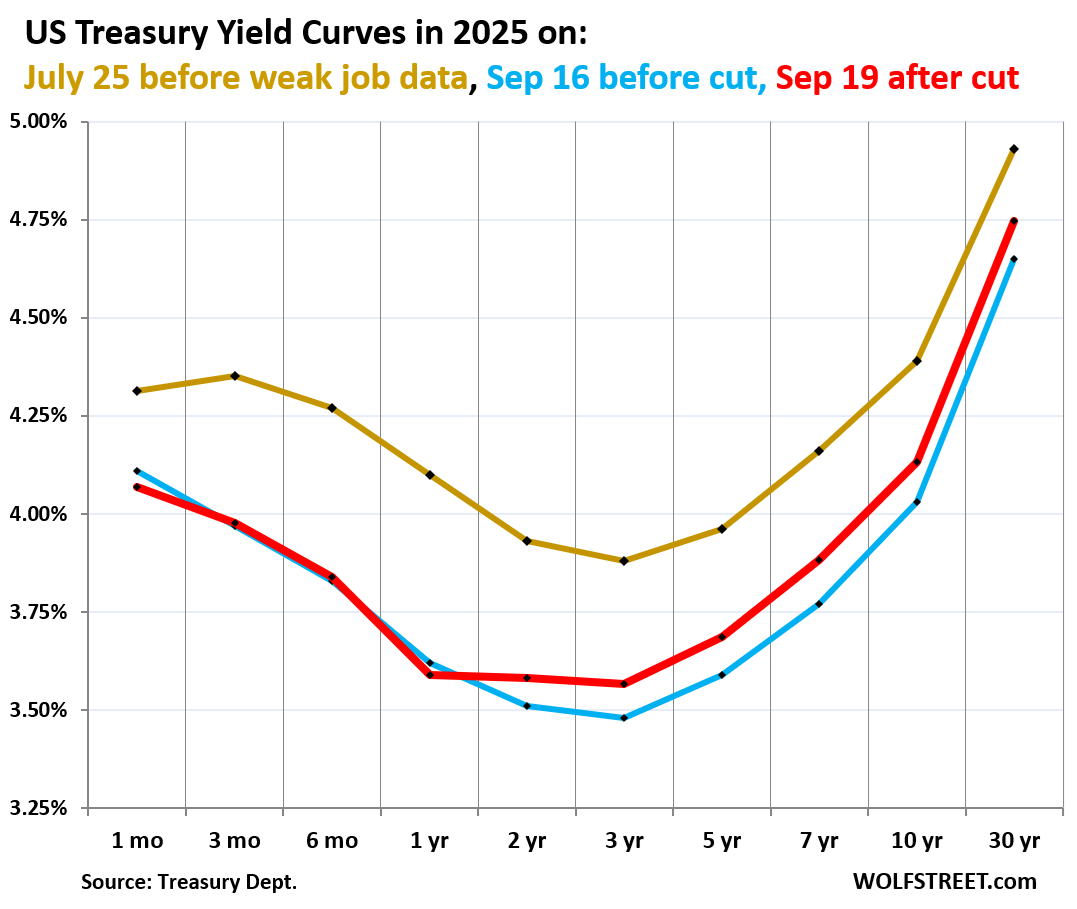

Yield curve steepened at longer end after rate cut.

The chart below shows the yield curve of Treasury yields across the maturity spectrum, from 1 month to 30 years, on three key dates:

- Red: Friday, September 19, 2025.

- Blue: September 16, 2025, just before the Fed’s rate cut.

- Gold: July 25, 2025, just before weak labor market data overpowered hot inflation data.

The 1-month yield is boxed in by the Fed’s five policy rates (from 4.0% to 4.25%) and closely tracks the EFFR.

The shorter-term yields are moved by expectations of the Fed’s policy rates, and they’re expecting more rate cuts this year and next year.

But the further yields go out on the yield curve, the more they’re influenced by inflation fears and supply concerns, with the 30-year yield being the ultimate test of them.

So from the two-year yield on out, yields have risen since just before the rate cut by:

- 2-year: +7 basis points

- 3-year: +9 basis points

- 5-year: +10 basis points

- 7-year: +11 basis points

- 10-year: +10 basis points

- 30-year: +10 basis points

Cutting policy rates during inflationary times is a delicate operation that has the potential of turning the bond market into a scourge. If inflation settles down in the 2% range, no problem. But if it continues to accelerate as it has done over the past few months, with services inflation being the big driver, and goods inflation chiming in and making it worse, then the bond market’s reaction to a lackadaisical Fed could get ugly.

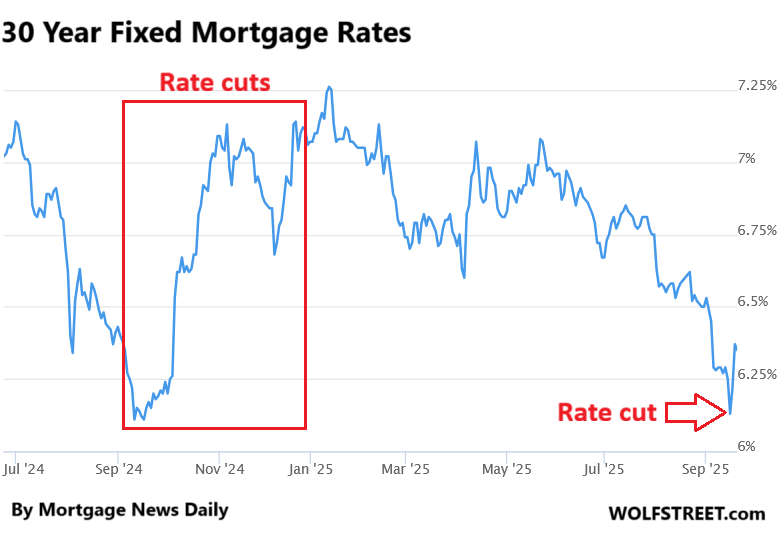

Mortgage rates have jumped more than Treasury yields: the daily measure of the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate by Mortgage News Daily has jumped by 22 basis points since just before the rate cut, from 6.13% on September 16 to 6.35% on Friday.

This is about double the increase of the 10-year Treasury yield over the same period, a replay of what happened a year ago after the Fed’s big rate cut.

These mortgage rates of 6% to 7% are now only a big deal because home prices exploded by 50% and more during the two years between mid-2020 and mid-2022. This home-price explosion was caused by the Fed’s reckless monetary policy that created 30-year fixed mortgage rates that were far below the raging inflation rates – better than free money, and when money is free, prices don’t matter.

But that’s a bubble-pricing problem now that should have never occurred, not a rate problem. The rates are fine. They’re historically at the low end of the normal range. The 5% and below mortgage rates were a creature of massive QE during the Financial Crisis and after, when the Fed loaded up on trillions of dollars of Treasury securities and MBS to push down long-term rates. But the Fed has been doing the opposite since the second half of 2022 and has shed $2.4 trillion of those securities as QT continues.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Ugly it is. So many factors at play. Afraid this 4 quarter will be dicey.

Was that a pushmi-pullyu interest rate move?

Right now the real estate market is dead here in the Swamp. The only houses on the market are dogs, (S$hit ass properties that nobody wants). No one in their right mind will give up their 3% mortgages and trade them in for a 6 to 7% mortgage unless they have to. Some Condos are coming on the market from investors who have finished converting rental apartments to condos. That’s it. Realtors here may as well start looking for a new career as nothing is going to change anytime soon. They are SOL (S$it out of luck)

Seems like every time the Fed cuts rates, the bond market freaks out even more. Mortgage rates jumping while inflation’s still hot doesn’t feel like a good combo.

Dead and/or dying here in 33703 also SC.

One year ago there was nothing for rent or for sale here.

Now so many I lose count when walking with the boss around the hood.

Some builders have stopped starting; others, apparently not reading the wolf’s wonder have not yet stopped.

Going to be very interesting to see the next couple months, maybe even couple years from the POV of NO debt, etc.

We continue to hope POB will come to understand the VAST delta when intelligent young folx wanting to reproduce can see so clearly it is WAY beyond their current financial ability.

WE, in this case ALL of us working folx, can hope,,, eh

Great point to bring this up VintageVNvet, especially of how the housing bubble is crushing the US birth rate and pushing America into a demographic crisis too, among other terrible effects. Family and friends all over the country in once affordable areas, in Ozarks, Nevada, Utah, even Idaho and Montana has been furious about how the fiscal and Fed’s over-stimulus since even before Covid has done the opposite of saving the US economy, instead setting off this inflation mess and unaffordable housing making family formation next to impossible.

Even the Mormons, traditional evangelicals and Catholics, old Amish and Mennonites are now seeing a huge fall in birth rates all over the USA, and it comes down to same thing, can’t start a family if you can’t afford a home. There’s a good reason home prices have stayed around 2 to 3 times median income at most all through history instead of 5 to 6 times now, if you make homes unaffordable for couples of childbearing age (and then add inflation of healthcare, college, elder and daycare and groceries) and then add lack of job security, and you take away the financial foundation to start families. Our foolish leaders should of realized that you can’t over-stimulate an economy like this to generate fake wealth. There’s no such free lunch and it’s being paid for by the collapse of the American family formation among other things, the more they try to postpone the bubble pop the more they’ll wreck American demographics. The jump in mortgage rates alone, after the Fed rate cut, is just another indication that monetary gimmicks can’t hold back the flood of market forces any more.

“THEY” are likely NEVER going to allow things to correct as the COST to rebuild and handle the mess at time of explosion is far worse than keeping the bubbles expanding.

A war or a massive black swan is the only way things correct at this point.

After all, who has the most to lose financially if bubbles burst?

Who will be the first class the masses go after if their families are hungry?

Too big to fail indeed.

Somehow the WW2 generation managed to raise 3-5 boomer kids in little 2 bedroom, 1 bath bungalows all across America. Maybe they accomplished the impossible?

Or maybe the whole trend of houses getting bigger while households get smaller reflects changing cultural expectations about how people expect to spend their money, and what has value?

We’re many times more prosperous than the boomers’ parents, but we place a greater value on automotive luxury and HOAs and streaming services and iphones and empty hobby rooms for us to accumulate purchased junk in. People are conciously choosing these things, and then declaring they don’t have enough money for kids. It’s consumerism > family.

@Chris B

Problem is those little 2 bedroom, 1 bath bungalows all across America the Boomers bought are also outrageous expensive now from Housing Bubble 2, so it’s not just matter of consumerism and wants over needs. Millennials, Zoomers and alphas just can’t afford even basic starter homes anymore,

I’ve met plenty of young couples including relatives who’d love to start out in little bungalows like that and start their families, but even those modest starter homes have soared in price way beyond incomes. The data backs this up–through most of American history, Boomers and other generations homes were at most 2 to 3 times average household income, with the Everything Bubble they’re now 5 to 6 times average household income or even worse in some markets. Even this underestimates how monstrous unaffordable the Housing Bubble 2 has made US homes, because a “household” for the Boomers more often meant just 1 income, now it’s almost always 2 (or more) incomes from both members of the couple have to work, and even then, home prices are an even worse multiple of that. Add in expensive healthcare, daycare, care for parents, college, no family leave and the US is basically set up now to crush our fertility rates here even lower.

So it’s not that young American couples are uninterested in those modest starter homes, millions are and probably not unlike the numbers for Boomers, it’s that those homes too have literally soared in price due to historic failures by the Fed and Congress to reign in over-stimulus over decades (starting well before JPow and then getting worse in the pandemic) This is the harsh price of asset bubbles and fiscal and monetary irresponsibility, it can wreck countries by making family formation ever harder. Even worse when joined with inflation in nearly everything else.

Now I don’t disagree there’s a lot of dumb excessive consumerism in the USA and I’ve seen it myself with our own family. I can’t tell you the number of times we’ve had to give a stern scolding to someone around us making a stupid purchase of a car way beyond their means and getting stuck in high interest 72 or 84 month loans (one got repoed earlier in summer), or throwing money out the window on an iphone upgrade they absolutely do not need. So yes, that factors in for many. But problem is, even the younger couples who do things right and stay more frugal, resist the consumerism siren song are stuck too because prices esp housing are so detached from the realities of income and savings.

The nasty reality is that with those past monetary sins, we’re stuck in a corner and family formation in the US will be difficult without a major correction in home prices to pop the bubble. Countrybanker’s posts hit the nail on head but we’re talking about 50 to 60 percent reductions in home prices across a lot of major markets throughout the United States, to even start coming back in line with the historical average multiple of median incomes makes a house affordable. The longer we try postpone it with monetary gimmick, the more painful the unavoidable correction becomes.

The smart existing home sellers in the US will realize this and exit sooner than later, cut their losses–or still even then for most, hold on to some gains even with price declines esp if they bought pre-pandemic and have equity–and come out OK. The FOMO’s still stuck in delusion will ride the bubble pop downward and this time, with this much debt and years of fiscal mismanagement, there’s nothing to come to the rescue like in 2008. The US dollar itself is on the ropes, and the bond market won’t allow it.

shift to fiat money, requires debt to keep the ponzi scheme going chickens coming home to roost. but I guess the national debt numbers doesn’t matter – the bigger the better.

All is not lost for out of work Realtors here in the Swamp. Just up I95 is NJ where they have a law against pumping your own gas. There are Help Wanted signs all over advertising for Gas Station attendants. Starting at $18/hour. Go for it!

Dude. Listening to Thoughtful Money podcast (historically they interviewed Wolf).

New homes now on average $365,000. Existing home average around $415,000. The builders see reality of what you describe. And they respond. Mind the gap mate.

Wonder if they will invite Wolf back? Last time he challenged their doomer/recession is around the corner narrative…and since then more doomer analysts been on the show, with George Gammon being on recently being the icing on the cake..

Very understandable and predictable.

The US economy needs the bubble to burst.

It was wrong to inflate a bubble

It still is wrong for the FED to protect the bubble with lower short term rates.

All assets are priced too high

70% of the population owns a nominal amount of these assets

They lose no direct wealth from letting the bubble deflate on its own. The small job losses and future lower wage rate gains are worth deflating the assets.

The wealth effect, which used to increase spending by 50-60% of citizens, now only affects about 20% of citizen spending.

GDP, which is the wrong way to measure the health of US economy, will go down.

Who will be damaged by letting the bubble burst? The top 20% of households who own 90% of the wealth.

Stock market…..who should care. The owners who own on margin knew the risk, same for their lenders.

Bond market will be fine. Maybe true price discovery helps guide bond market; and stock market.

The housing market needs to drop 50% in most markets. Older, long time owners lose only the fake gains they thought they may have had.These owners are not leveraged.

The recent young buyers will be screwed. But some of them knew the risk.

The banks, who have loaned far too much on bubble asset values will have to eat the losses as the real estate market resets. Regulators, who are knowingly allow extend and pretend must stop this. Force the legal remedy of foreclosure, get the foreclosed housing stock back on the market, let Mr Market clear the excess with pricing. Many banks should fail and clear that market as well. No FDIC payoff of uninsured depositors either.

The CRE market is ripe for its own clearing.Developers and investors are big boys and girls, just like the foolish bankers who loaned the money.

The pensions and 401k accounts will be devastated, but the bubble values were fake gains. People will need to save more and spend less to build their nest egg.

Speaking of saving, why have the powers to be (deep state control of Congress ) felt it was correct or fair to put the thumb on the scale to help borrowers at the expense of savers. The savers are good people. We need to encourage savings so we have a pool of funds to loan to developers and entrepreneurs, instead of printing money at the FED.

and the Fed, how much worse could they perform on their duty of price stability and preventing currency ($$$) devaluation. The $ dollar of 1971 now with a penny! High school students throwing darts could have done better.

Do not open up the federal housing agencies from their current government control. Do not re-privatize. Actually, liquidate them. Let the private market fill in and grow. By the way, how many countries have a fixed rate 30 year mortgage guaranteed by their governments. This product helped create the housing mess.

The US economy needs real, transparent,unsubsidized markets and price discovery. Price discovery emanating hundreds of thousands of players each attempting to improve their lot in life, is a system that investors and the public a look to for stability.

All the government fixes, crony capitalism, GREENSPAN puts, do-gooders attempting to lower housing costs for the masses via subsidies, etc have ruined our economy. And do not try to say our economy is healthy.

Let’s go folks, support taking our medicine. Let’s get off the debt drug. Let’s get off socialism and crony capitalism. Let’s take our pain we have coming…AND GIVE OUR CHILDREN A CHANCE.

They will do the opposite of everything you say.

And our compliance with what happened in the past is why they will do it again.

Until you are ready to drag these people from their homes out of anger of what they’ve done to your children’s future, it will continue.

The billionaire and hundred millionaire pukes who are the beneficiaries of the FED’s “no billionaire left behind” QE BS are peacocking all over social media and the financial shows, flaunting their “success.”

A big AMEN!

Will we take our medicine?

Maybe, but the gold market is telling a different story.

Tightening my seatbelt.

B

GREAT post on here Cb, and thank you for being not only clear, but clearly and carefully thorough…

Almost as good as Wolf!!!

Can’t agree with you MORE, after being in the RE mkts (with dad and grandad to be clear) for many decades going back to at least the early ”oughts” of the last century.

IMO, when the manipulations of the FED, clearly only a puppet of the banksters, despite the vast propaganda otherwise, overrides any and every free market(s) WE, in this case WE the PEople, suffer, as should be SO clear to every person, and especially every investor.

Nice plan, but it requires acceptance of recessions. The Fed doesn’t appear willing to sign on to that.

The Fed is like a cancer patient willing to explore all treatment options, except those requiring a needle prick or pills.

Voters don’t seem willing to accept recessions.

By voting out whoever was in office when a recession occurred, we’ve given politicians the message that we want the business cycle cancelled.

OK, they said, but the method to do that is socialism.

We then asked if the numbers keep going up.

Sure, they said, and gave us a pat on the head. Sure.

“The housing market needs to drop 50% in most markets. Older, long time owners lose only the fake gains they thought they may have had.These owners are not leveraged.”

Amen and totally agree with this….do I think this will ever be allow to happen or will happen over the next couple of years? I give it about as much of a probability of me winning the next Powerball…As I always say, would love to be wrong about this.

CB, I generally agree, and that’s half the fix.

The financial markets and state of monetary policy are symptoms.

The other half of the cure (if my recently invested “401k bubble money” is cut in half?!?) is the wage equation.

We see profit margins at ATHs, which is the folly that supports absurd valuations.

The 70-90% of whom you’re speaking, are often not even saving money! The rising costs of living in all aspects are largely keeping up with wage gains (both sides of this equation have jumped in recent years). The aggregate numbers look “ok.”

Aggregate is not a representation of the masses! I live in a HCOL area and have a mortgage (thereby slightly leveling the increase of housing costs). Even then, I have an older building and insurance has spiked, repairs are basically unattainable and the situation seems to be deteriorating (with the exterior of my home!).

The days of rewarding loyalty have been gone for decades already, and even a True living wage is elusive in many areas!

Of course, the average American wants to live and work online, and trades and construction are dominated by New Americans.

Personally, I’m baffled by the proposition that ”AI job destruction” could decimate a generation: then I remember: righty tighty, left loosey is no longer common knowledge.

The executive class doesn’t even know this, but believes $20/hr is a sort of gift to a caste-style slave class.

This person helps me see the grand manipulation of it all….

The truth here is the financial market do not want the baby boomers to:

1. Take their money out of the stock market.

2. Take the equity out of their homes.

In effect destroy the financial markets in spite of holding on to both, wisely, for many years.

Screw all those who would keep Baby Boomers from cashing in….

Saw this happen in 2009. Many here know the old adage of How they TELL you it is and how it REALLY is….

This is just amazing to see in print.

You talk like a socialist. I am a capitalist. I want mine if you want to do this go ahead but, wouldn’t you know it, this guy is hoping to cash in on the big short.

Great and thoughtful post Cb, it hits so many nails on the head. A home is for sheltering and living in, not for investment and this speculative frenzy, and housing bubble has already done incredible damage to the US society. Including demographically, when the Fed ZIRP, QE and MBS buying and the Covid fiscal over-stimulus and PPP fraud inflated the biggest asset bubble in American history, there was no real wealth created, just inflation and a terrible costs-of-living crisis for Americans anywhere.

One of the nastiest effects is the collapse in the US birth rate that may now be too late to reverse, going from the historical average of homes at 2 to 3 times median income to 5 to 6 times income now, makes even starter homes unaffordable, has utterly demolished childbearing and family formation all over the US and pushed America into a demographic crisis. Then add in all the inflation and bubbles in healthcare costs, caring for kids and adults, college, car loans, even groceries (not to mention little parental leave here) and you have one of the most anti-family economies in the world now.

Like you say the only solution is grit our teeth and taking the medicine for the market forces to correct the bubble excesses like should of been done years ago. Wolf’s article here is more proof time has run out on all the financial recklessness, the major spike in Treasury yields and rates–after a Fed rate cut, no less–is just another painful splash of ice-cold water to the pivot-mongers that the gimmicks won’t work anymore. Any more doomed attempts to manipulate interest rates or other monetary or financial gimmicks just prolong the inevitable correction in prices to fall in with incomes, making things even worse with even more inflation and collapsing of the US dollar.

The one and only solution to the monetary and fiscal over-stimulus and corruption since even before the pandemic is to step back and let price discovery and market forces re-adjust, with a massive drop in home prices. Any deluded sellers need to step away from all the excuses and realize home prices have to correct way back downward for something even so basic as Americans able to start families again. Better to take the bitter medicine sooner than later.

Too big to fail is the operative term here….

Can you imagine our mass media brainwashed lemmings actually having to gulp “suffer” in a down turn?

After being told for eons that they deserve to have a house, 2 cars, a vacation home, expensive wardrobe, etc?

Sadly, the powers that be likely have the entire situation under control and wreckless interest cuts in the future just may be a part of the so called “plan”.

So far, Jerome has shown the cajones to stick to his guns, can any human withstand the pressure on him now and likely to triple if the economy even goes south a percent or two?

Countrybanker,

Getting off of socialism? It of course depends on how you define it but most countries with affordable health care, affordable secondary education, and so on are happy to have those basic things. Agree on the crony capitalism but there is no removing something that benefits the ruling class. When material conditions change for enough people perhaps there will be change but I am highly skeptical as even though in the French revolution the working class fought the battles they saw little in the way of real material change. We are more than a decade into the decline of the US empire and while it won’t go away, nor will it happen quickly, it will never be what it was before. And you can tell by the leaders actions that they will not adapt to the changing world but attempt to hold on to the past. In the end this is a great thing.

Well said Countrybanker!

bubbles. plural.

Just as expected. Just as predicted. Don’t these people ever learn?

It’s so widely reported and predicted that maybe that’s exactly what the Fed WANTED to happen.

If the Fed didn’t want the long end of the yield curve to rise, then why would they continue QT at any rate?

The world changed on “Liberation Day”, Wed. 2 April 2025 and there was an immediate panic, but it has taken until the start of Q4 for the cracks in the whole system to really start to show. Are we in for a boiling frog or a Wile E. Coyote future?

“…what’s this box on the front porch marked ‘ACME MOBILE HOT TUB’?”

may we all find a better day.

Date that rate right? LOL, I’ll be lying if I say I am disappointed to see these RE agents and MSM will continue to loose steam on this narrative. Guess whoever they were able to sucker into this narrative recently with the drop in mortgage rates, better enjoy it while it last. At least for the mortgage brokers, they got some uptick in refinance business.

NAR, please be creative with your next BS narrative to drum up FOMO…these same old rate drops and never ending price increase talking points is getting really stall and lack any effort.

They’ll say something ridiculous like mortgage rates are high because there’s so much demand for them.

@Phoeniux_Ikki

Clearly they suckered me. Under escrow right now on a new build condo masquerading as a 2 story SFH with a 1% rate buydown using seller credits. Builders are desparate, and wife and I couldn’t wait any longer unfortunately since we want to start a family.

I will say the only reason I feel reasonably justified is that the home was initally listed $100,000 higher and the last couple that fell out of escrow put 30K worth of upgrades into the house. So there’s *technically* “$130k” worth of equity built in.

Plus I wrapped the solar into the loan, which sounds like it will come in handy with electricty rates that are about to skyrocket because

Of course, the house is only worth what people are willing to pay for it, so I’m coping hard. I’ve resigned myself to the fact that I may be underwater for a few years. But this is a life decision for me and the Mrs., and at least I’ll have a home in a trust before WEF’s Agenda 2030 makes the rest of us permanent renters.

For those on here still looking for a primary residence, I pray you all find affordable homes that you can make your own at the price you’re willing to pay for it. I imagine that will happen next year when the recession hits.

Should read “electricty rates are about to skyrocket because all of these big AI data centers drawing massive power resources and making everybody else subsidize it.”

Regardless of the market, you bought for all the right reasons. You may go temporarily underwater, but as your children grow up, you will have quality of life. In the long run you will prosper.

same here. got a great deal on a new build spec home, plus builder credits worth a lot. But we are not going to carry a mortgage very long.

Wolf, I’d say some solid steepening is good news, but I fear that will encourage the administration to put even more of the debt they’re racking up and refi’ing on the front end rather than distributed around.

Damn, we DID create a FrankenMonster!

What’s next is anybody’s guess.

I’m not taking any responsibility for this current FrankenMonster.

Thank you.

It’s not nothing that Fed still holds $3 trill Treasury securities and MBS.

Harry

Balance sheet is about 6.5 Trillion

Old job just cut 5 bids, the drivers on them are working whatever piecemeal crap comes down the line.

Landlord’s son just got placed on hold for work. Had to drive 200 miles for his last 3 weeks of work. At least 2 weeks with no jobs lined up.

I and a few others at my new job are going to 4 day work weeks since we are a common carrier and just lost a contract we were fulfilling because the other company has slowed down.

Like everyone says, housing won’t drop dramatically until the job market goes to crap. Over here in the trucking world, things have been a mess for years but it’s actually starting to get pretty bad now. Might be a long cold winter.

I still think a lot of younger people are sitting on the sidelines waiting for prices to come down enough for them to qualify for a mortgage. Until they are out of work in large enough numbers to chill demand, I don’t see much in the way of a major housing correction. The low end of the market is still selling like hot cakes here.

It USED to be, the DJT (Dow Jones Transportation Index/ NOT the meme stock) was a forward looking indicator of overall economic activity.

Now that the most valuable things are bits and bytes (including NFTs, Crypto and OnlyFans), we shall see how it plays out.

The index hit the ATH on a spike in Nov. ‘21, and failed to make an attempt to close higher than that day in question, until Nov/ Dec ‘24.

I imagine it rose then, in anticipation of the “stimulative rate cut.” The effect was unseen and by liberation day had slumped to hover above the pre-pandemic high range.

The 5 years of sideways movement sums up the consensus of the ”real economy.” We continue to wait for:

The Recession that Never Came

MSN: Cryptocurrencies sink as $1.5 billion in bullish bets wiped out

$1billion, out of $4 Trillion total cap.

It’s a long way down!

I checked the chart, that’s $150Billion today.

ATH Total CryptoCrap was $4.17 Trillion, about a month ago. Higher than I expected, breaking above the peak to peak trendline.

With today’s pullback: it’s still just testing an eye-watering steep uptrend line, that exploded off the post- liberation day pullback.

If the whales really are using the bitties and bytes to make their inflation hedge: the sky is the limit.

Money is just made up in the first place anyway, right?

Wolf,

Thank you.

I would like to ask you if a steeper yield curve aids in the bank’s stability? I would assume that making it easy for banks to borrow overnight at lower rates and lend over longer terms at higher rates would increase banks’ ability to write down bad loans.

If so, and most of the US economy “runs” on the longer-term rates, then significantly higher long-term rates might curtail inflation better, while a steeper yield curve keeps the banks stable, so the Fed doesn’t need to intervene again like after the SVB crisis?

Or does this not work like this at all?

The vast majority of the costs of funding for banks are deposit rates. Despite some higher CD rates, deposit rates are near zero in checking accounts and in many savings accounts, and are zero on most transactions accounts, and on the massive float.

The total amount of deposits = $18.3 trillion, but only $3.6 trillion are CDs.

Banks raised the interest rates only on some of those deposits. For example, Wells Fargo has $1.33 trillion in deposits (of which $970 billion interest bearing, and $361 billion non-interest bearing). Compared to $400 billion in other forms of debt. Only its special offer CDs carry higher interest rates. The rest of its deposits have near zero interest rates or are non-interest bearing.

So banks continued to be hugely profitable during this higher-interest rate environment, despite larger write-offs. For example, Wells Fargo made $5.5 billion in Q2 in net income.

So a steeper yield curve due to lower short-term rates might not impact banks much since their short-term funding costs are already so low.

Higher long-term rates would increase their profitability further. So if long-term rates come down due to rate cuts, bank profits might come down too. So this could go in different directions.

But the Fed is not at all worried about the current profitability of banks, because it’s HUGE. Banks are swimming in profits despite larger write-offs.

Makes sense.

Thank you.

It’s wild how banks get away with 0% or 0% plus a monthly fee accounts, when it is so trivially easy to get an alternative.

The Fed is trying to make water run uphill….

rates never went high enough to flush the excesses, the poorly leveraged, and to deter debt creation from fiscal irresponsibility’s.

It all changed in 2009…..the Fed will save … no more business cycles.

Have you heard about the “soft landing”? They ve been talking about it for nearly a decade.

Interesting context for the budget showdown (gov’t shutdown) likely to occur 24 Sep which is essentially a demand to sustain huge Biden era spending.

A huge driver in all of this has been gov’t spending. The Fed’s problem is consistently arriving at the scene of the accident months to years after it occurred – while contributing their own QE/NIRP excess.

The whole political system is [fill in the blank]; and has been for a long time.

Why should the goverment be setting interest rates is the question!

Ever hear of free market capitalism? I know it is just a talking point and not real!

The next step is to just print and skip the sillyness of selling bonds and having debt that will never be repaid.

Hang on to those Yuan, sorry I ment Dollars!

The government does NOT set interest rates. That is what the free an enormous US TREASURY MARKETS DO. The only rates set by the Federal Reserve are 5 very short term interest rates and nothing more.

QE 2008-2022. Fed purchased long term treasuries. This lead to interest rate repression on the long end. So sick of this crap about the Fed only affecting short term rates.

Well, DB, what I stated is how it works normally and the Federal Reserve has been doing QT for many years now so has no impact at all on the yields on long-term US Treasuries which rose nicely today to 4.15% on the 10-year and will continue to rise.

The gov and the Fed have to constrict RE supply before the boomers

die. In 2008/09 the Fed saved the banks and the RE market. If they didn’t ==> it will take decades to rise from the ashes. The US as a superstate is gone. The last thing the gov needs is another financial crisis caused by bank’s RE assets collapse, including Fannie and Freddie. RE might stay at high plateau for a decade. It will not drop to 2009/2011 prices.

Since 2002/03, from the base of bubble #1, most asset made an A-B-C up. Houses were up between x2 and x5. SPX from 800 to 6,700. MIT and Stanford from $36K/Y to $90K/Y. Gold from $8000/kilo to $120,000/kilo.

This time tax payers are taking the risk if people start defaulting on their mortgages.

Some of the once hot housing markets like sfo and Austin are already down more than 22 percent from their peaks and going down even more as we speak.

The real estate prices have to crash to bring sanity to society and price downturn is already happening despite hot economy and historically low unemployment rate

Gold is just a metal and is one of the most preposterously and laughably inflated assets in the universe of assets of which it comprises less than 1%.

LOL! Then why is every central bank on the planet acquiring as much as they can…? Oh yeah, for 6,000 years gold remains the ONLY collateral with zero counterparty risk.

Hey dipshit, RISK is being repriced. Globally.

They’re not. Central banks own about 35,000 metric tonnes of gold now which is about the same amount as 10 years ago and the total amount of gold in existence is only about 190,000 metric tonnes which is less than the size of two Olympic swimming pools and which is worth about 1% of global assets. The only thing being repriced is the speculative price of gold and that is now severely hurting its major customer namely the jewelry industry.

LOL! Your numbers are off, moreover, you didn’t address the issue of collateral against bank currencies. This is not speculation. It’s simply the world waking up to the amount of bank notes circulating globally.

I did the following for fun years ago when I had too much time on my hands. I obtained the prices of various goods and assets (e.g. bread, coffee, gasoline, my house on zillow, and of course gold) denominated in nominal dollars. Then I calculated the prices of the various items denominated in gold instead of dollars, and graphed them over time.

Next, I obtained CPI estimates going way back (there are estimates going back to pre-civil war out there), and calculated the price of gold in inflation adjusted dollars (e.g. 2015 dollars, or pick your favorite year), and graphed it over time. Maybe you’ve done something like this, but if not I recommend it. It’s illuminating.

So I think what the Dude is saying in a colorful way, is that in the bigger arc of history, people are paying too much for gold right now. For example, why is it worth double what platinum is now, or why is its ratio to the price of silver 1.7x what it was 20 years ago, or why has my house in a desirable area gone down in value by 25% when denominated in gold? Food for thought?

” The last thing the gov needs is another financial crisis caused by bank’s RE assets collapse, including Fannie and Freddie. RE might stay at high plateau for a decade. It will not drop to 2009/2011 prices.”

But the price of this sort of monetary meddling would basically be the demographic destruction of the United States, because continued artificial inflated housing prices is the main factor makes it impossible for young American couples to start a family. Even for high paid professionals both couples have to work longer hours, leaves less time energy and money to raise families, multiply that by a nationwide housing bubble and you have formula for total demographic collapse in America. Like I wrote even for the Mormons in Utah, Mennonites, old Amish and other groups the US TFR fertility rate is falling fast. You can’t start a family if you can’t comfortably afford a home with job security (not even getting into inflation in healthcare, care for kids, college..) That and the total collapse of whatever’s left of the US dollar as reserve currency, although some in power seem to want that now. So, pick your poison. Either let the RE assets and other assets collapse to sensible market values and recover from the recession, or see an even worse collapse in other parts of American society that we’d never recover from.

And I doubt the Fed is so afraid of such an asset collapse, Wolf himself has pointed this out, since the reforms of the GFC the banks aren’t on the hook anymore for a real estate crash, investors and taxpayers are. So we’re not at risk of the kind of banking crisis we saw 2008 and 2009. It sucks for highly leveraged investors and FOMO fools but that’s how investment and speculation work.

It isn’t even just housing, right now the S&P, Nasdaq and rest of the US stock market is being fueled by massive margin debt by FOMO retail investors. Nvidia has basically lost it’s China market as the companies and fabs over there develop their own GPU chips and EUV and yet speculators just take out more margin debt for it, and then there’s TSLA and PLTR valuations and margin debt buying. And this before we get into the crypto swamp.. We’re in an historic speculative asset bubble that’s spread to housing, let’s get real, it’s just fantasy to think there can be a “soft landing” to pop bubbles for excesses this ridiculous.

Just keep an eye on gold if you want to see where things are going. Bitcoin is no substitute for gold. The Treasury market is split into two markets, the government run short end and the real market at the long end. Real Estate and stocks are volatile.

Gold doubled in 2 years in USD. Seems volatile.

After this Mexican standoff farce of the debt ceiling the credit rating companies like S&P should lower the US down a notch. That will never happen because the president might get mad.

How long and how much can you run up the credit cards before your toast?

Reminds me of Arthur Anderson auditing Enron, and deciding they’re such a good client we’ll keep this fiction afloat a little longer.

Yea, put them out of business.

Great analysis Wolf…as always. How interesting the Sep ’24 rate cuts…right in the middle of the Presidential campaign and to which the 10 & 30 years acted sooo poorly. It would be foolish to say, wouldn’t it???, the Fed acted then to add a wee bit of encouragement for the Biden/Harris/Dem strategy!!! I’d be halfwitted, foolish, and a right-ring fanatic to even mention such a thing, because we all know the Fed to be Independent, Non-Partisan, and a Board of Economic Experts who act solely & only in good faith to support the American economy…PJS

“the Fed acted then to add a wee bit of encouragement for the Biden/Harris/Dem strategy!!!”

And now the Fed acted to “add a wee bit of encouragement” for the Trump/Vance strategy?

We do know that in the summer of 2024, a lot of bad labor market data, including huge downward revisions, came out, and that the Fed acted on this rapidly deteriorating labor market data.

And now we have a parallel of this.

“I’d be halfwitted, foolish, and a right-ring fanatic to even mention such a thing,”

No, it just means you’re gullible, and trust in radio/tv/Internet personalities that are b.s.’ing you.

The Fed could have cut 100bps in Sept and it wouldn’t have made a bit of difference in the economy and voters’ decisions just 7 weeks later. GMAFB. More likely, Trump and Co would have slammed Biden even more about the economy, citing the rate cuts as needed, an emergency. Sheesh.

Seriously? Tighten that tin foil hat.

There was plenty of non-political justification for lowering interst rates in 2024. I didn’t agree with them at the time, but I understood them. If you do not understand the non-political reasons for lowering rates, it just is an indictment of the sources of information you use.

Use better sources of information and you will look more intelligent. That is why Wolf is worth reading.

The Fed might be fine with longer rates at 4-5%. But they probably want to pull that 4-week down to 3.0 or less and straighten out the yield curve. Considering that the Treasury is going to issue a lot more bills and fewer bonds, the concept of “T Bill and chill” has cost the gov’t a lot of interest.

Unless the means-of-payment money supply increases, R-gDp will fall in the 4th quarter of 2025.

I’d rather own bonds than stocks. Stocks have had it.

The most important price or cost in the eCONomy is the price/cost of money itself.

Go ahead Jerome, cut some more, I triple dog dare you.

Full Faith and credit…

“but we had it before, namely a year ago, when the Fed cut by 50 basis points at its September meeting, and the bond market got spooked by the sight of a lax Fed amid accelerating inflation. ”

Slightly incorrect. We did not have “accelerating inflation” before the Sept 2024 FOMC meeting. The Aug data (released in Sept) had shown YoY inflation falling every month for the previous 5 months. The annualized previous 6 months of inflation (CPI-U seasonally adjusted) was 2.01%. The annualized previous 3 months (June, July, Aug) of data was 1.27%. CPI-U was still falling at this time.

And in case you were referring to other inflation measures: Core PCE had somewhat stalled at 2.7% YoY, but was not accelerating by Aug’s report (annualized previous 6-mo was 2.50%). PCE Seasonally Adjusted YoY was 2.28%, the lowest it had been since 2021, so definitely not “accelerating”.

There really wasn’t “accelerating inflation” showing up by the 2024 Sept FOMC meeting. Which is why they were comfortable cutting.

Month-to-month CPI 2024, annualized:

Jun: 0.0%

Jul: +1.7%

Aug: +2.2%

Sep: +2.8%

Oct: +2.8%

Nov: +3.4%

Dec +4.5%

Jan 2025: +5.7%

But, but: how DARE you thwart my narrative with DATA!?!

We’ll see through this data, as we see fit!

(Did I mention, my seeing eye “dog” will be guiding me?)

Looking at the same data:

That blue line had the Fed really concerned by August, that historically high overnight rates were strangling the economy. That in conjunction with bad labor statistics led them to urgent rate cuts.

But about as soon as the emergency rate cutting campaign was underway, the numbers flipped. Inflation started to rise in Aug, Sept, and October, and so the Fed stopped.

They somehow landed on the neutral rate, because inflation for most of late 2024 to mid 2025 was flat, zig zagging around 2.5%.

In hindsight, a recession didn’t occur as many indicators were warning, so maybe the rate cuts were the correct call. But also, the Fed failed for yet another year to reach their 2% target, leading people to question Gov. Goolspee today about whether the new target was actually 3% (I mean, the data fit, and they just did a cut after a Core PCE read of 2.9%).

If Chuck shuts down the gov bc of Medicaid, rates will be cut to 3%, gov spending will be lower, ex the dept of war and unemployment checks. If in Q2/Q3 onshore industries start hiring, along with tariffs, lower rates, student loans collection and a much smaller gov ==> debt might be lower by a 1/3 within a few years. Global investors trust a currency (DXY) of a country which significantly cut debt. Boomers retirement peaked between 2023 and 2026 (1958+65, 1961+65). So, retirement is beyond peak. Trump will be the first president who cut debt and who brought back industrial job.

No interest rates are going to be cut to 3% and if anything they would rise dramatically if there were to be a government shutdown.

LOL! Great sarcasm.

Debt and deficit exploding under Trump. So much for listening to DOGE.

If, if, might……

Wolf,

Your article was posted on seekingalpha.com

“seekingalpha.com/article/4824727-longer-term-treasury-yields-mortgage-rates-jump-rate-cut-yield-curve-steepens-bond-market-edgy”

Thanks

Wolf

Many of my articles have been posted on SA for many years. I ask them to limit reposts to one a week, but sometimes they go over. No biggie.

They also put them behind a paywall … not sure if you’re aware of this. I hope they’re giving you a cut …

1. Yes, I’m aware of it.

2. No I don’t get a cut. To get paid for articles, authors have to give SA an exclusive. My years-long arrangement with SA is that I publish my stuff here, and they republish what they want, but limited to one a week.

The Fed mandate to keep long term rates moderate would appear to be derivative of its inflation mandate and indeed long-term rates can be viewed as a leading indicator of inflation…

kramartini

The Fed’s unspoken third mandate was ignored for at least a decade…..and it is from this deliberate violation that our current problems derive…from a broken real estate market to inflation.

“Moderate” means “not extreme”, and that door swings both ways.

We had RECORD LOW long term interest rates promoted, manufactured by the Fed….and record lows are “Immoderate” by any definition. Yet then we got the “Dual Mandate” game in which the inconvenient 3rd mandate was omitted…because the Fed was in constant violation.

Re: This phenomenon of rate cuts causing long-term yields to rise is rare

I attribute that to a massive unprecedented insane deficit and budget, complimented by unprecedented insane Treasury issuance.

Wolf – I’m emptying my piggy bank 🐖 and all the Benjamins 💵 I’ve stuffed under my mattress for the last 30 years. Do you wanna go in on a discounted office tower in the City by the Bay with me? I’d like to find one at 80% off. 🤓

We may have to remodel and rent it out as condo units. 🏢

Several comments above about the Boomers- just for reference, search for “Generational Death Clock” on google, click the link on incendar dot com. All the generations are listed. Here are stats for Boomers:

US Baby Boomers Dead

37.5661377 %

Total 85,358,000

Alive 53,292,296

Dead 32,065,704

Death every 14.4 Seconds

5,993 Deaths Today

There are still more boomers than my generation. (X) My parents are/were Silent Generation, one of which is still kicking… I’m posting this because perhaps the people reading this site and comments might find it interesting, as I do, and it sometimes helps to get an idea of generational scale.

Thanks,

Tom

Tom H,

Il mio nome è Nessuno: “The secret to a long life is you try not to shorten it.”

Neat website. Thanks!

Just resume the $50B QT rolloff.

When the markets see an adult in the room things will stabilize.

If the jobs numbers are correct (a big IF) and if core inflation continues to rise, we have stagflation. Good luck to the Fed on dealing with that.

Wolf,

Do you think the FOMC is cutting rates into a headwind of rising inflation because they (or the politicians who influence them) fear a continued bursting of the housing bubble?

I.e. do they think they are lowering mortgage rates when the push down the overnight rates?

And if so, do you think the recent trend of long-term rates rising as short term rates are cut sort of blows that thinking out of the water, because long term debt markets are now more concerned with long-term inflation than with tracking the FFR?

Yields seem to go up when the government does something that is long-term inflationary, such as cutting rates long before the 2% target is hit.

“Do you think the FOMC is…”

That’s not how I see it. What the Fed needs to do to get mortgage rates down is get inflation down. Powell said as much many times during the press conferences when challenged about mortgage rates. Short-term policy rates have little influence on 30-year fixed mortgage rates. Mortgage rates are driven by the long-term bond market, and the long-term bond market is driven by inflation expectations. A lax Fed amid rising inflation scares the bond market and they see higher inflation rates in the future, and they want to be compensated for that additional inflation risk by addition yield = higher mortgages rates.

So the Fed is clearly not worrying about mortgage rates. It bought into higher for longer and seems to be fine with mortgage rates where they are.

Right now they’re worried about the weak and inconsistent labor market growth.

Putting 2 and 2 together to predict the near future:

If the Fed’s lackadaisical behavior increases inflation expectations…

At the same time as labor market growth falls…

Then… mortgage rates rise at the same time demand for housing purchases falls.

Stagflation…. could get interesting.

Wolf,

What are your thoughts on the BLS’s delay to the Consumer Expenditures report, which sets the weights used to calculate CPI? Is it fishy and suspicious, given the political pressure, or just a quality control move?

https://www.bls.gov/cex/notices/2025/ce-2024-reschedule.htm

People are fantasizing about everything and then douse it with sugar and homemade conspiracy theories.

The key phrase of the linked notice is: “BLS plans to update the spending weights of the Consumer Price Index as scheduled.”