It could be that Chinese stock market participants have no idea that there is something wrong beneath the officially rosy covers. Or they might already know in granular unofficial detail, and fearing the worst, they’re wagering everything they have, plus some, on stocks to get rich quick while they still can. They’re opening up brokerage accounts at record pace and borrowing on margin to ride the wave. If the limits in China get in the way, they head to Hong Kong to set up trading accounts and borrow even more.

It has worked so far. The Shanghai Composite Index jumped 8.9% this week and 146% over the past 12 months. It closed above 5,000 for the first time since 2008. The valuation of companies with a primary listing in China skyrocketed by $4.7 trillion this year. People are feeling flush and are hoping for a another governmental tsunami of money to bail them out. What transpired in other countries over the past six years is now transpiring in China in condensed form. And the countdown for the crash has started [read… The Dumbest Man in China].

One thing the Chinese authorities cannot do is crank up the global economy and demand for Chinese goods. These goods are shipped by container to the rest of the world. But containerized freight rates from China have totally collapsed.

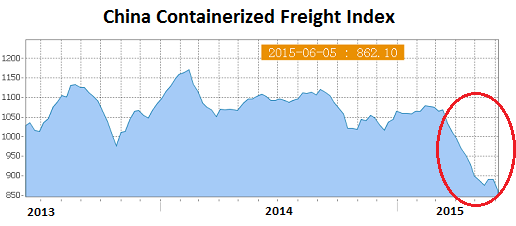

The China Containerized Freight Index (CCFI), operated by the Shanghai Shipping Exchange and sponsored by the Chinese Ministry of Communications, has not been put through the beautification wringer that other more publicly visible statistics, such as GDP growth, are subject to. It tracks spot and contractual rates for all Chinese container ports. And it plunged 3.2% this week to a multi-year low of 862, down 20% from February.

The trajectory of this terrible 3-month plunge:

For perspective, the index was set at 1,000 on January 1, 1998. Today, the index is 14% below where it was 17 years ago!

The pricing dynamics in the spot market of containerized freight – so excluding contractual rates – are reflected in the Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (SCFI). It’s reacts more quickly to changes in spot rates than the CCFI. It gives an unvarnished if noisy view of the immediate pricing environment for containerized freight from Shanghai to major destinations around the world.

This week, it plunged another 5.8% to 623, the lowest level in its history. It has now collapsed 43% since February. The index was set at 1,000 on October 16, 2009; today’s reading is 38% below its level during the Financial Crisis!

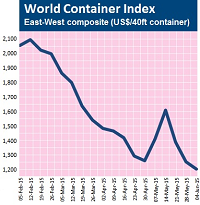

The same sort of gloom shows up in the World Container Index for routes from Asia to the Americas and Europe, which Drewry cites: it has plummeted 45% since January to $1,200 per FEU (forty-foot container equivalent unit).

The big jag in the chart, starting at the end of April and collapsing in mid-May, shows that carriers have tried to impose hefty rate increases but couldn’t make them stick. Now they’re hoping, because it has failed so many times before, that the next round of rate increases might stick.

And all this while fuel costs have jumped, with bunker fuel up 22% since mid-March to $335 per metric ton for IFO 380 in Rotterdam (chart). Collapsing shipping rates and soaring coasts make a toxic mix for carriers.

It’s not just containerized freight rates. The Baltic Dry Index, that has been tracking the price of shipping major raw materials by sea since 1986, is hovering near its all-time low set earlier this year!

Maritime shipping rates are a function of supply and demand. On one hand, demand for goods manufactured in China has been weak, and perhaps getting even weaker. A reflection of the state of the global economy along with a China-specific problem: multinationals are diversifying their supply chains to cheaper countries.

This already dreary scenario is made worse by an oversupply of shipping capacity. Since the Financial Crisis when the Fed and other central banks have started flooding the world with cheap money, executives have swallowed hook, line, and sinker the meme that this would fire up the economies in the US, the EU, and around the world. They were drunk with the very optimism that central banks were purposefully spreading around luxurious C-suites.

In a historic leap of faith, they ordered a large number of ships, including monsters that can carry 19,000 containers and are too large for many ports. Ships take years to build. Now they’re going into service, even as the carriers are confronted with a sobering reality: despite the flood of money, or perhaps because of it, the global economy has remained stuck in low-growth mire. What’s left are inflated asset prices and overcapacity that has demolished, among others, commodity prices and shipping rates.

But inflated asset prices face a New Normal: “volatility and repricing” – a euphemism for losses. Read… Get Used to Selloffs, Central Bankers Say as They Fret about the Terrifying Moment When Liquidity Evaporates

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Thanks, Wolf for this coverage. As gravity overcomes the FEDs smoke and mirrors reality is going to be difficult for many. For the prudent, 2008 was the opportunity to retrench and prepare. I suspect that time is running short.

Michael,

astutely put!

the cost of shipping indicates very little….we need the number of containers to determine changes in amount of commerce. wolf..,can you find those numbers? Chipper

Chip, container rates indicate supply and demand. So there are more factors going into it, as I pointed out. Number of containers shipped from China would be a measure of pure export volume of manufactured goods (regardless of overcapacity problems among carriers). If we could trust Chinese numbers, we should see reality play out in their monthly exports numbers when they report them. They haven’t been great either, but they’re widely reported, so I don’t normally write about it.

Am confused by your statement, “container rates indicate supply and demand. What about efficiencies, which would lower rates ?

“Efficiencies” as in larger ships? As I pointed out, they’re putting those in service, which adds to the oversupply … hence pressure on rates, which makes the situation worse. You probably meant to ask if those larger ships would lower costs for carriers, so that they could lower rates. The cost savings of the 19,000 FEU ships are currently hotly disputed. And even if they shave off a bit, it would be rather small compared to the collapse in rates. On many of these routes, particularly from China to the EU, rates are only a fraction of breakeven for carriers.

Efficiencies or not, those numbers are terrible. Costs have risen across the board, inflation, etc. Those factors alone easily add 100% to the price over 17 years.

Any chance some of that volume loss is going out to smaller importers through dhl, fedex, ups?

A tiny part maybe, if any. Fedex, UPS, etc. ship by air, and in terms of tonnage, air freight only handles a minuscule part of total freight.

We got the Chinese import and export numbers for May today (Monday Jun 8) …. they are not good.

Exports fell for the 3rd month in a row (in value, not containers): -2.3% year-over-year

Imports crashed: -17.6% year-over-year (after -16.2% yoy in April). Something seriously wrong in China.

Exactly, shipping rates reflect that the capacity is out of whack with demand, but it doesn’t tell me demand is down.

What if demand for shipping is at an all time high, but that supply is also at an all time high. Then rates might be low. It’s too hard to tell.

The problem is dual, as I said in the article: lackluster demand for Chinese goods AND overcapcity of ships. For the demand side, check the export numbers for China, down for the 35rd month in a row!

For the export numbers and the current conditions of the Chinese economy:

http://wolfstreet.com/2015/06/10/hard-landing-says-china-momentum-indicator-cmi/

I am not sure how to tie this with Germany factory orders growing by 1.4% and the 288K job report. Seems like Asia is rapidly slowing, but everywhere else is doing not bad?

It’s about quality. Chinese products are crap and German products the best. Hardware is a good example. My husband had a custom closet company and the best hardware was from Germany and not that much more expensive. He attempted to cut cost by buying hardware manufactured in Mexico and it was terrible, when that got outsourced to China, it was worse. The closets were collapsing due to the hardware and it was an expensive lesson.

Well Europe was very close to recession as well with their QE easing program only getting under 2% growth is pretty easy. Also the US jobs a lot are part time and low wage, plus “unemploynent’ went up with those added jobs.

Seeing a slowing China is easy to see, plus the euro was shorted with their QE so its cheaper to buy European goods as well.

I’m buying stocks that can weather the looming meltdown. Like small cap IT companies that have long-term support contracts with essential government agencies (e.g. Main Roads Dept, Police Dept. etc.). When retailers meltdown they’ll stay healthy with revenue streams and may even climb as investors catch on and jump ship. McDonalds, Sears etc. are already toast.

In the next meltdown, Chicago is just the tip of the iceberg. Long term contracts? Smells like pension.

The most visible problem for Chinese factories (and by reflection, containerized freight) is the storm that’s building up over big box stores in both Europe and the US.

For over a decade these outlets seemed to be doing no wrong. Even in the bleakest days of 2009 and 2010 they carried the day and have been regularly offered as proof “recovery is here” and consumers are ready to spend until they drop: they just need a tiny monetary policy adjustment.

Last year troubles started surfacing, but were brushed aside: as is usual when it comes to economic news, laughter and optimism are the code words.

This year they’ve started hitting like a sledgehammer. Even IKEA, a company that could do absolutely no wrong, has started laying people off. Until last year, not a decade ago, this was completely unthinkable.

All these companies are prodigious importers of Chinese consumer goods: in a way it can be said they could barely exist without China providing them a constant flow of sweaters, dishware and garden implements at rock bottom prices.

This is not an isolated phenomenon, a single sector being beset by internal issues. It’s just a symptom of larger issues looming at large.

The most obvious issue is real wages in the whole West have been moribund for two decades. China came to the rescue with her cheap finished goods but it was only a matter of time before Western consumers would stop buying those goods at the same pace as in 2007 and 2008.

And you want to know the reason for that blip in manufacturing in Germany, the US and elsewhere? Take a drive on the road and look at the number of new cars. We are squat inside yet another automotive bubble financed by cheap money.

One may be forgiven for not seeing the connection between people not having the money to buy a cheap Chinese lawnmower but getting a brand new SUV, but consider this: you can buy a car on credit. Interest rates on auto loans have literally collapsed in the last year and a half. here some manufacturers offer EAPR’s as low as 1.54%. We are almost at 2007 levels. Auto loans are also getting longer: 60 months financing is not unheard of… and the manufacturer often gives you the option to return the car after as little as 24 months and renegotiate financing for a new model. As my mother commented: “This is the road to eternal serfdom”.

In short, unless general consumer credit gets yet another bubble going, only goods that can be bought on credit are doing fine right now. The CCFI will probably rebound as we get closer to Christmas and stores will step up their orders of fake Christams trees and the like, but don’t expect miracles.

Consumers all over the world are leveraged to the hilt and getting deeper in debt every day. And this is on top of having crummy wages as well.

In spite of what Mr Draghi and Mr Kuroda seem to think, this cannot go on forever: unless both men embark in one of the ridiculous “money from the sky” experiments regularly proposed my monetary crackpots, the party must not only end, but people should also be forced to clean and tidy up the house as well.

Otherwise we’ll soon find ourselves in an even bigger mess sooner than we may like.

Very good comment. I guess if you are going to get a new vehicle, a SUV is a good choice. It is more roomy for the time it becomes your house. I read awhile back that 72 months was not uncommon for new auto loans. I guess I need to buy a new hat and a tasty one at that, because if this cosmic sheet storm ends well, I will have to eat it. Actually, I may have to eat it however it ends.

Too many people have rushed into the shipping business. Low rates are mostly from too much competition, not too little being shipped.

The liner shipping industry is run by corrupt idiots who have no inkling of finance, common sense or business. They deserve to all be bankrupt and I hope that happens.

George Hearn, Howard Finkel, Tim Marsh, the list goes on.

The movement of freight is capital intensive and requires both a specific skill set and a psychological hardiness to being away from home for long periods of time. This is true for truckers as well as ship crews…there are jobs that get you home more often but each has its own set of stressors. Truckers as a component of the blue collar set are aging as a group, and it is hard to recruit young people. It is hard work and while some of the younger people still have work ethic it seems to be a smaller percentage.

Trucking is hard work. Did a little of day tripping as a young lad. It made me stronger and I learned from the experience and it is part of who I am today. I am afraid many of the young today have unrealistic expectations, although, the coming new normal may alter that. Not all fall into that category. Those are the ones who will persevere and build the future.

There is a glut of container ships — because projections of demand have not been realized.

This is ultimately a demand problem

Cool story. I live in Hong Kong where I work as a financial journalist and I found this story insightful. Regards. Chris