Investors are still lusting after yield, any kind of visible yield, as long as it is positive, no matter what the risks, and they’re throwing record amounts of money even at junk-rated companies.

Nevertheless, stung by a series of bankruptcies and defaults, investors are now drawing the line at a growing coterie of energy companies. These companies are dependent on a constant flow of new money that they burn through to keep operating. When that new money has second thoughts, the companies wither. That’s now happening. But other junk-rated companies are shoving as many junk bonds out the door as possible before that door closes.

In March, $38 billion in junk bonds were sold, S&P Capital IQ/LCD reported. It was the best March ever.

Following a record-breaking February, when $32.1 billion in junk bonds were issued, and a tepid January, it brought the total for the first quarter to $91.6 billion, up 22% from the already hot pace last year. It was the largest Q1 tally since 2012.

The healthcare sector was by far the biggest issuer, at 25% of total junk-bond volume. The largest deal was Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Of the four tranches, three were in dollars for a combined $8.5 billion.

The energy sector used to be the biggest issuer of junk bonds. That money funded much of the fracking boom that blew up so spectacularly. Many of these companies have been cut off from the capital markets. So in March, the energy sector accounted for only 15% of total junk-bond volume. And for those energy companies that were still able to sell junk bonds at all, it was a mixed bag. LCD:

On the more stressed side, Comstock Resources and Energy XXI both issued highly structured secured offerings in the first week of March that yielded 10% and 12%, respectively, but both issues underperformed in the aftermarket as oil prices later retreated.

Senior unsecured offerings from Whiting Petroleum, Calumet, Rice Energy, Sunoco LP, Crestwood Midstream, Antero Resources, Newfield Exploration, and Lardeo Petroleum priced far more easily at much lower coupons, and also had better success in the aftermarket.

Investors weren’t so lucky. In March, returns were, according to LCD, “dismal, at negative 0.47%.” In LCD’s flow-name sample, the average bid had “plunged” 201 bps, to 99.53% of par on March 31 from the end of February.

March had been tough: Quicksilver Resources went bankrupt; Samson Resources warned that it might go bankrupt; Allied Nevada Gold, American Eagle Energy, and BPZ Resources defaulted; etc. The bloodletting was heaviest in the first half of the month, “amid technical pressure from outflows and heavy issuance,” as LCD put it. But then on March 18, the Fed once again stepped in to save what it could with its “dovish” statement. The subsequent rally band-aided some of the wounds.

But leveraged loan issuance is grinding to a halt. Banks that extend these loans to junk-rated companies usually try to repackage these loans and resell them, either to loan mutual funds – where retail investors end up with them – or as Collateralized Loan Obligations.

Regulators, including the Fed, even Yellen personally, have warned banks about these leveraged loans for two years. Banks risk getting stuck with them. Leveraged loans were a factor in the Financial Crisis. Junk-rated companies that issue them are rated “junk” for a reason. And even as regulators are cracking down on banks to cut their exposure to leveraged loans, banks are already taking losses on them again [read…. Wall Street Banks Hit by Oil & Gas Defaults, Bankruptcies].

So banks are backing off the leveraged loan business. And despite three large M&A loans – Dollar Tree ($6.2 billion), Valeant Pharmaceuticals, ($5.15 billion), and Ball Corp. ($3 billion) – issuance “sputtered,” as LCD put it, to $80.7 billion, the lowest first-quarter leveraged-loan volume since 2010, down 52% from the same period in 2014.

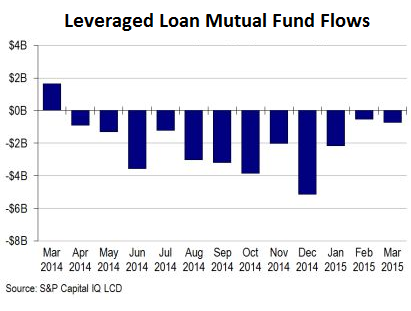

Retail investors have soured on them too. In March, they once again yanked their money out of leveraged-loan mutual funds, for the 12th month in a row! What a relentless trend:

So are leveraged loans finally dead? Um, not quite.

Turns out, leveraged loans that get sliced and diced and repackaged into CLOs are hot. Bank regulators are fretting about these CLOs because banks retain some risks. Banks would take a hit when these often highly rated CLOs turn toxic as the companies begin to default.

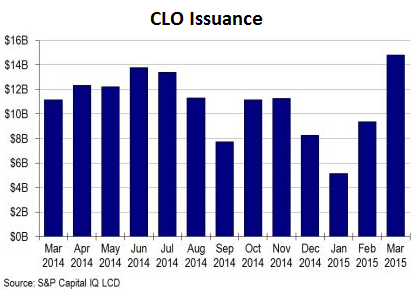

But investors are clamoring for CLOs, and banks are more than happy to provide them, as S&P Capital IQ LCD reported today with this breathless headline: “US smashes records; Europe hits post-crisis high in 1Q.”

Year-to-date, US issuance of CLOs reached $30.4 billion from 56 deals. That’s up 22% from the same period last year. And March issuance of $14.8 billion in CLO’s – toxic or not – set a new all-time record:

So fewer leveraged loans make it into the new-issue pipeline, thus constraining supply. Retail investors are bailing out of loan mutual funds, thus lowering demand. But demand for CLOs is booming. And this has, mirabile dictu, supported leverage loans in March, despite “the weakness that infected other risk asset classes,” as LCD put it: on average, the price of S&P/LSTA Index loans edged down only 4 basis points in March. In other words, prices didn’t budge.

And so continues the greatest credit bubble in history. Parts of it are already self-destructing. Cheap seemingly endless credit has created overinvestment and oversupply that caused a collapse in commodity prices, among others. As long as companies still have access to new money to burn through, they can avoid hosing their old investors. But once the new money dries up, old debt suddenly becomes toxic. This is happening now, company by company. But it hasn’t yet motivated yield-desperate investors, driven to near insanity by the Fed’s zero-interest-rate policies, to demand proper compensation, or any compensation, for these risks.

The free-money policies have also pushed startup “valuations” to a state of delirium. Read… It’s Just a Question of Whose Capital Will Be Destroyed

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

There is such a disconnect going on between what I read in the contrarian world and the pablum that passes for news on commercial radio. This morning I heard a talk show conversation with Brothers International who had just released a survey of small business people who are feeling better about the economy and are investing in their businesses again and see the light at the end of the tunnel. I thought WTF, don’t they know it’s an oncoming train? I drive all over this country, and with a few exceptions I see empty malls, plants and warehouses. I shop in stores that aren’t closed but are half empty, obviously cashing in their chips. Not a day goes by that I don’t see a furniture store with a big banner saying GIANT GOING OUT OF BUSINESS SALE. Don’t they see these things, too? Or are they like Eddie Willers to whom it has become normal? Darned if I know. I just drive the big truck.

Credit expansion shifts a greater proportion of existing purchasing power toward bankers (who create the new credit) and their favored clients (who borrow the bulk of it). The smaller proportion remains for everyone else.

At the same time overall purchasing power declines as it is equal to the resource capital that is destroyed (consumed). With the passage of time, ordinary citizens have less of less: less capital and less of a claim against it.

Easing/low interest rates accelerate the claim-shifting process. Fewer customers able to borrow = less a bid for industrial products such as crude oil. The problem is not mal-investment leading to oversupply but structural undersupply and compensating increase in new loans.

The outcome can be seen as war spreads across the oil producing regions of the world and the oil markets do not seem to price this in. Either the markets perceive world peace breaking out or that the world’s customers are bankrupt.