Even the soothsayers and Abenomics spin doctors expected a downdraft after Japan’s consumption tax was jacked up to 8% from 5%, effective April 1. But not this.

The tax hike had been pushed through parliament by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s predecessor. It was supposed to save Japan. But no one wants to pay for government spending. The tax proved to be so unpopular that Prime Minister Noda and his government were unceremoniously ousted at the end of 2012.

Japan is in terrible fiscal trouble. Half of every yen the government spends is borrowed, now printed by the Bank of Japan. Expenditures can’t be cut, apparently, and government handouts to Japan Inc. had to be increased. Yet something had to be done to keep the gargantuan deficit from blowing up the machinery altogether, and it was done to those who spend money.

The consumption tax is very broad, impacting goods and services bought by businesses and individuals, from haircuts and vegetables to construction materials. So the 3-percentage-point increase would be levied on much of the economy.

But here is the thing: money that people and companies keep in the bank earns nearly nothing, and even a crappy 10-year Japanese Government Bond yields less than 0.6% per year. But if buyers frontloaded major purchases by a few months or even a year to beat the consumption-tax increase – buying that refrigerator or heavy-duty truck a year earlier than they normally would, for example – they’d save 3% of the purchase amount. That’s pure income. And tax-free for individuals. The biggest no-brainer in Japanese financial history.

Every company and individual frontloaded whatever was sufficiently practical and substantive, and whatever they could afford. It started late last year and culminated in the January-March quarter. As a result, GDP soared at an annual rate of 5.9%, a phenomenal accomplishment for Japan.

The Japanese have been through this before. Ahead of the prior consumption-tax hike from 3% to 5% effective April 1, 1997, consumers and businesses went on a buying binge of big-ticket items. The economy boomed for a couple of quarters, then woke up with a terrific hangover as spending on durables by businesses and consumers ground to a halt, and the economy skittered into a nasty recession that lasted a year and a half!

But this time, it’s different. On March 23, about a week before the tax hike would take effect, the Nikkei polled corporate executives as they were still floating on a sea of optimism from all the money that rampant frontloading was bringing in faster than they could count. They weren’t concerned: 70.2% said that sales would remain stable or decline no more than 5% in fiscal 2014, which started April 1; 55.4% said the economy, supported by strong consumer spending, would improve by September, and 74.3% saw that happening no later than December. So no big deal.

Alas, the Ministry of Economics, Trade, and Industry just released a dose of reality. Total retail sales in April plunged 19.8% from March and were down 4.4% year over year. But this includes sales of perishable and small items not suited for frontloading, and convenience-store sales (which rose a smidgen). In stores where people buy durable goods, such as appliances, watches, or cars, sales were awful.

At “large retailers,” sales swooned 25.0% from March and 5.4% year over year. At supermarkets, where people also buy some durable goods, sales fell 3.9% year over year – people even stocked up on non-perishable food and beverages. At department stores, where people buy jewelry, designer clothing, or French purses, sales fell 10.6% year over year. It wasn’t just retail. Sales between businesses – nearly 2.5 times the value of retail sales – plunged 20.4% from March and 3.7% year over year. In short, it was the largest decline in sales since March 2011, when the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami that killed over 19,000 people, brought commerce to a near-standstill.

Those sales were in prices that had been inflated by 3%. That tax-hike money doesn’t stay with the seller but is turned over to the government. In actual merchandise sales, the scenario is 3 percentage points worse. So sales at, for example, large retailers on a comparable basis dropped 28%, not 25%.

At the end of January, the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association (JAMA) forecast that passenger and commercial vehicle sales would dive 9.8% in fiscal 2014, to 4.85 million units, the lowest since earthquake year 2011. JAMA’s prediction was pooh-poohed as catastrophist.

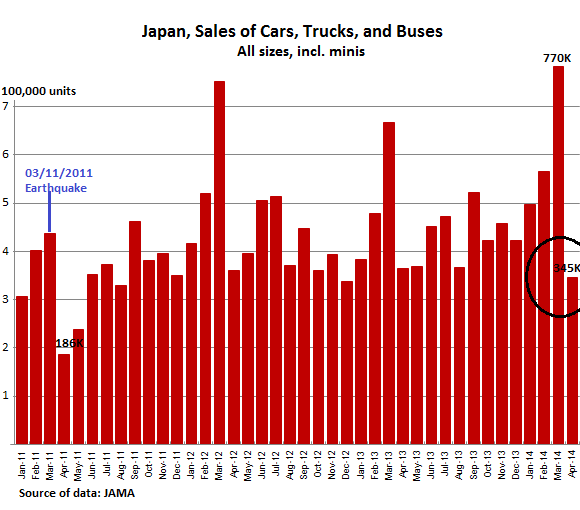

Turns out, the good people at JAMA are optimists; vehicle sales got demolished in April. As measured by registrations, all categories plunged: new cars, including minis (tiny cars with tiny engines) -56.0% from March; trucks of all sizes, including minis -54.0%; and total vehicles sales, retail and commercial, cars, trucks, and buses -55.9%, from 783,384 units in March to 345,226 units in April.

It was the worst performance since December 2012 (December being historically the weakest month of the year in Japan) when the economy was still suffering from the aftershocks of the earthquake nine months earlier. Here is the chart of that epic collapse in total vehicle sales:

Most of the vehicles sold in Japan are made in Japan – despite decades of screaming by US automakers, which have yet to get their foot in the door. This means production schedules are going to get cut, hours will be reduced, component purchases will be whittled down…. It has already happened. In April, production was cut by 18% to 770k units, including export units, which are doing well. And the whole chain reaction of a large complex manufacturing sector slowing down will worm its way into the statistics over the coming months. Same as in 1997.

The slowdown will add to the slowdown already underway in business and consumer spending on durable goods. And all the hype about the phenomenal January-March quarter and how Abenomics was performing miracles, and how consumers were finally starting to spend is already turning into furious spin-doctoring as economists are fanning out to explain that this time, it’ll be different, that April was just a blip, that all this frontloading won’t lead to a long recession, as it did last time.

And on May 30, the hapless Japanese consumers woke up to find out officially what they’d already figured out on their own: inflation in April had soared 3.4% for all items from a year earlier, with goods prices up a dizzying 5.2%. But their incomes have been stagnating. The wrath of Abenomics is slamming them: inflation without compensation. Inflation mongers will be ecstatic, but this can’t possibly be good for the Japanese people, or the economy.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()