Boeing has squirrelled away more orders in the first quarter than archrival Airbus, which has been plagued by delays of its A350 and by lousy sales of its super-jumbo A380, and by a million other problems. So on the eve of the ILA Berlin Air Show, Airbus CEO Fabrice Brégier spoke up against this ridiculous injustice. And true to his Frenchness, he exhorted the ECB to get busy and do what central banks are supposed to do and devalue the euro. It would help exports, and particularly Airbus’ exports.

Devaluing the currency was France’s standard go-to solution back when the franc still existed. So, for example, after a series of devaluations since 1945, France “revalued” the franc in 1960 at 100 old francs to 1 new franc. Three zeroes were chopped off, new notes and coins with confidence-inspiring designs were put into circulation, and then the dance started all over again. Over the next 40 years, until it was replaced by the euro, the “revalued” franc lost another 88% of its value. In the process, France continued to lag behind Germany as an industrial power, and Germany had a hard currency. That’s French monetary policy if left to its own devices.

The ECB “has to gain credibility” on how it manages the currency, Brégier said, according to the Wall Street Journal, perhaps reminiscing fondly about the good old days of the franc and its serial destructor, the Bank of France. He fingered the US and Japan whose central banks have been printing money hand over fist. Neither central bank has put currency devaluation on its public list of things to accomplish. But that has been the result, with the dollar and the yen chasing each other to the bottom. Regular Americans and Japanese have been paying the price for the devaluation of their currencies, but that didn’t come up in Brégier’s speech. It doesn’t matter. It never comes up. It’s a taboo topic. Currency devaluation and inflation are laudable goals to be accomplished quietly and without ruffling the feathers of their victims.

He considered the strong euro in relationship to the dollar one of the principal threats to Airbus and lamented that the ECB’s suggestions of negative deposit rates haven’t produced any results yet. “Europe politically has to do what it costs to make it happen,” he said because his bonus might be at stake.

But a couple of days before he opened his mouth in Berlin, Natixis, the asset management and investment banking division of France’s second largest megabank, Groupe BPCE, preemptively issued a new report in his native tongue to prove him wrong.

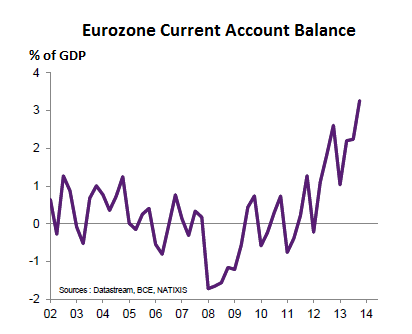

In fact, since the beginning of the debt crisis, the Eurozone has had a growing current account surplus. And ironically, despite Brégier’s protestations, the stronger the euro, the greater the surplus:

Natixis found that these current account surpluses have contributed to the strong euro, along with foreign investors who have been plowing the Fed’s and the Bank of Japan’s freshly printed money into European financial assets, thus inflating their values. And the study concluded what everybody can see by just looking at the numbers: the appreciation of the euro has not reduced the current account surpluses.

But there were differences between countries. Natixis found that exports by Germany (and countries like it) are not sensitive to the euro’s exchange rate due to their level of differentiation and sophistication.

Exports by other countries, however, are sensitive to the euro’s exchange rate, but some of them, like Spain and Portugal, are benefitting from their growing cost-competitiveness – low salaries, in normal English – and have seen strong export growth. Other countries, such as Italy, are at the limit of their external debt, and current account deficits cannot increase. So if the strong euro hurts their exports, domestic demand for imports must contract to prevent external deficits from reappearing.

France, the report points out, has a competitiveness problem (cost of labor has continued to rise in relationship to the lagging sophistication of production) and a profitability problem, which cause not only the weakness in exports but also the weakness in investments. And that’s not the fault of the euro or of the half-heartedness with which the ECB has been fighting the currency war, Mr. Brégier, but of the policies in France, the report almost added.

So when Brégier claims that devaluing the euro “is the condition of additional industrial development in the Eurozone and so additional exports,” he is firing a gratuitous shot in the currency war to push the ECB in that direction. Devaluing the euro would boost the paper profitability of Airbus as its dollar sales are translated into weakened euros, and therefore more euros. It would alleviate some corporate problems and raise his bonus payable in these devalued euros. But there are people who will pay the price, and as Natixis pointed out, it’s not a “condition of additional industrial development.” That shot went into his own foot.

Devaluation would allow France to paper over its economic and tax policy issues. But in the end, it would have to lumber, as in the past, from one devaluation to the next and destroy savings and wages in an insidiously sly manner, in the same sly manner actually in which the Fed has been destroying savings and wages of Americans for years. But Brégier should keep in mind that the one thing the dollar devaluation was supposed to accomplish – eliminate the huge trade deficit – is precisely what it has failed to accomplish.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()