Trade is one of the critical elements in Abenomics. Devaluing the yen would boost exports and cut imports. The resulting trade surplus would goose the economy. But the opposite is happening. It isn’t happening in small increments, with minor ups and downs, as it did in the US spread over decades, but rapidly and with a brutal relentlessness. It’s not energy imports that are driving it – they actually dropped! It’s because of a fundamental shift. And it doesn’t bode well for Japan’s economy, not at all, or for the new religion of Abenomics.

Exports rose 11.5% in September from prior year, according to the Ministry of Finance. It disappointed the wishful thinkers. Given that the yen lost about 20% of its value over those twelve months, export volume actually declined. But imports soared 16.5%, and the trade deficit hit ¥932.1 billion ($9.5 billion).

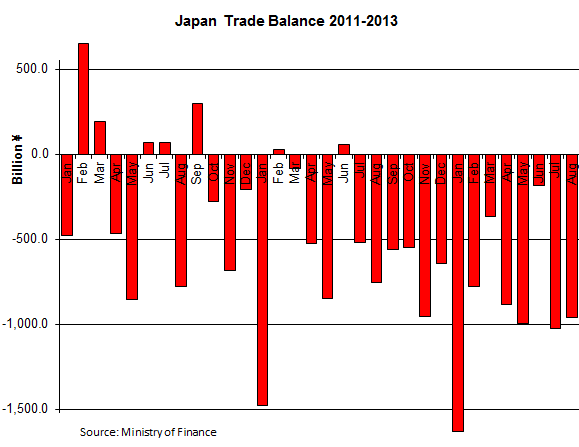

It was the worst September trade deficit ever. It continues a steep trend: August was the worst August ever, July the worst July ever, June the worst June ever, May the worst May ever. And so on! A trend that has been getting worser and worser, as they say. At a dizzying rate.

It was the 15th month in a row of trade deficits, the worst such sequence since anyone started counting, worse even than the 14-month series in 1979-1980. And there is nothing whatsoever on the horizon that signals a turnaround.

The September trade deficit was 66.7% higher than a year ago. By contrast, in September 2011, Japan had a trade surplus of ¥300 billion and in 2010 a surplus of ¥774 billion. Hefty trade surpluses in September had been the norm. For the 9 months, the deficit jumped 66% to ¥7.74 trillion from the same period last year. It more than sextupled from the same period in 2011. In 2010, Japan had a surplus of ¥4.9 trillion. An unrelenting, breath-taking deterioration.

The chart shows how the trade deficit in each month of 2013 deteriorated sharply from the equivalent month in 2012; and how those months had deteriorated from their equivalent months in 2011:

On the positive side for Japan is trade with the US as administrative barriers block US imports. The Japanese auto market, for example, remains hermetically sealed off to mass-market imports, and no Administration has been willing or able to crack it open. So the trade surplus with the US ballooned by 25% to ¥533 billion.

China and Japan might try to gouge out each other’s eyes, but they do trade. Nearly a quarter of Japan’s exports end up there, and nearly a quarter of its imports come from there. Neither country can let the political saber-rattling get in the way of trade. It would take down both economies.

Trade with China can be murky; a large portion of exports to China are transshipped through Hong Kong. So we look at China and Hong Kong as one. Exports to both combined rose 12.6% to ¥1.41 trillion, less than the yen devaluation, and actual volume declined. But combined imports soared 31% to ¥1.69 trillion, for a deficit of ¥287 billion. Japan used to be one of the few major countries that had trade surpluses with China. In the halcyon days before the financial crisis.

But don’t blame oil, natural gas (LNG), and coal for the soaring imports.

Imports of mineral fuels actually declined 1.0% in September. The only import category to decline! All other import categories jumped deep into the double digits. Among them: manufactured goods up 22.2%; machinery up 37.9%; electrical machinery up 46.6%, and within in it, semiconductors, up 59%.

Japan used to be a manufacturing powerhouse in the categories of “machinery” and “electrical machinery.” Semiconductors used to be one of the industries where Japanese companies were world leaders. But the entire industry is in the process of being phased out in Japan as companies have shifted production to overseas locations, and as foreign competitors have eaten their lunch.

The classic reasons for offshoring production of even sophisticated products – cheap labor and being closer to end customers – have played a role for many years. But the trend has gained momentum since the earthquake of March 2011, when companies were struggling with their supply chains, electricity shortages, transportation issues, and other hiccups. They could instantly reappear with the next major earthquake. One way around those problems was to diversify production to overseas locations. And it has spawned a relentless movement by Japanese companies to invest overseas, rather than in Japan.

Devaluing the yen doesn’t change that equation. It makes imports more expensive and the trade deficit worse. But it puts some cheap gloss on income statements as companies translate overseas revenues and earnings into the devalued yen. Yet they’re not repatriating the moolah, and the Japanese economy can’t benefit.

There is absolutely nothing on the horizon – not even a mirage – that indicates that this shift of money and production to entities in distant countries might ever slow down or even reverse. The real economy will bleed from these wounds, while monetary policy and gargantuan fiscal deficits are injecting addictive and ultimately toxic drugs into the system. Not a good combination.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()