Dirt cheap natural gas over the last few years has done wonders for America—and it’s not just cheap compared to oil and coal but cheap compared to history: the April 19 low of $1.90 per million Btu was a level natural gas hadn’t seen in a decade. Beneficiaries are scattered across the country: households with lower heating bills, industrial users, utilities, even companies dreaming of building Liquefied Natural Gas export terminals to benefit from prices that are several times as high in the international markets. Dirt cheap natural gas is spurring innovation and manufacturing and hopes for a brighter future. And yet, it’s tearing up the very industry that is producing it, and capital destruction—mostly borrowed money—has reached epic proportions.

The travails of Chesapeake Energy and other drillers have been well documented. Their problem: a debt-fueled binge in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) unlocked vast reserves—how vast is being disputed—of natural gas in shale formations across much of the US. And the very success of that binge ended in a supply glut that drove the price of natural gas from a peak of $13 per million Btu years ago into the historic basement.

The economics of fracking are horrid. All wells have decline rates where production drops over time. But instead of decades for traditional wells, decline rates in horizontal fracking are measured in weeks and months: production falls off a cliff from day one and continues for a year or so until it levels out at about 10% of initial production.

At today’s price of $2.43 per million Btu at the Henry Hub—though up 28% from the April low—drilling is destroying capital at an astonishing rate, and drillers are left with a mountain of debt just when decline rates are starting to wreak their havoc. To keep the decline rates from mucking up income statements, companies had to drill more and more, with new wells making up for the declining production of old wells. Alas, the scheme hit a wall, namely reality.

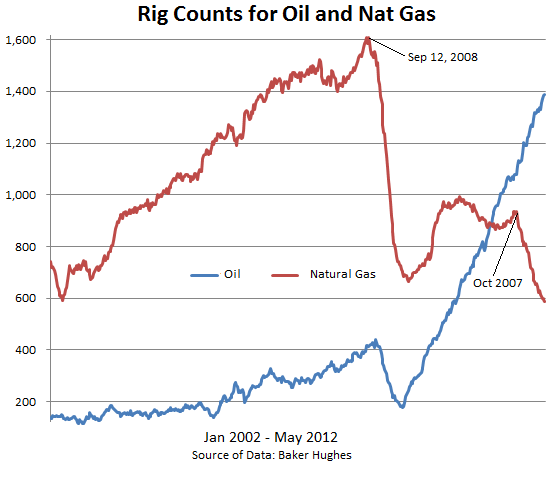

The beleaguered drillers finally reacted, cutting whenever feasible their operations in dry shales (fields that produce only methane) and concentrating on wet shales that produce oil—still a profitable activity—and gas liquids like propane, butane, and pentane that are priced more like oil. Result: a collapse in the number of rigs drilling for gas. From 936 on October 14 last year to 588 last week. A 37% nosedive in seven months. The lowest count since October 15, 1999. The rout appears to be far from over:

The natural gas business is brutal. The peak in drilling occurred in September 2008 with 1,606 rigs. Then the financial crisis threw it into a vertigo-inducing plunge. After last year’s mini-peak, the plunge continued. Meanwhile, drilling for oil has picked up the slack in the most spectacular manner. Drill baby drill.

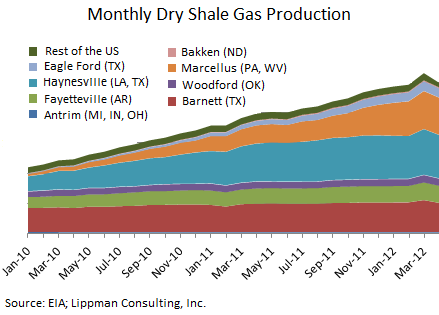

Production lags behind rig count, and while rig count for gas wells has been setting new decade lows, production has been rising month after month to new record highs. But lagging doesn’t mean decoupled. And someday…. Oops, it already happened. It has started. Production has turned the corner, and not just in one field, but across the US:

It’s still just a little notch in the curve. But it’s a sign that the collapse in rig count is translating into lower production numbers. And when the steep decline rates are beginning to overlap the drop in rig count, production will head south in a dizzying trajectory.

While drillers are getting slaughtered, power generators are laughing all the way to the bank. They have switched massively from coal to natural gas. According to the EIA’s just released Electric Power Monthly May 2012, net generation of electricity from coal-fired power plants fell 21.3% in March and 21.4% in the first quarter; but from gas-fired power plants it skyrocketed 40.2% in March and 33.3% in the first quarter.

The confluence of sharply rising demand from power generators and declining production has started to burn through the gas in storage—though still at a record for this time of the year. Fears were being mongered earlier that storage would soon be at capacity and that gas would have to be flared, thus making it worthless and available for free, bringing its price effectively to zero. This scenario now appears silly.

But there will be turmoil. Drillers continue to bleed. A cool summer could prolong the pain. It may drag out long enough to where some highly leveraged drillers that haven’t sufficiently diversified away from dry gas won’t make it. Their pain will continue until the price of gas rises to a point where fracking is profitable. Maybe $8 per million Btu for certain fields. And drillers, the survivors, will jump back into the game. But production can’t be turned on overnight. It will take time. Coal will become an alternative again for generators. And imports of LNG can pick up some slack, but with Japan paying north of $15 per million Btu, it’s hard to imagine that the US could buy it for a fraction of that.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()