No one likes paying taxes. You’d think. And it’s not just income taxes but a slew of other taxes. In San Francisco, we already have an 8.5% sales tax—but propositions to increase the state portion are worming their way onto the November ballot. At least we get to vote on it. And if it passes, it’s our own @#%& fault. In Japan, efforts to raise the national consumption tax from 5% to 8% by 2014 and to 10% by 1015 have led to a groundswell of opposition and a nasty political fight—yet Japan is the one country of all developed countries whose budget deficit and national debt are truly catastrophic.

But if my premise is correct that no one likes paying taxes, what the heck happened in Europe? Eurostat has just published Taxation Trends in the European Union, and it leaves reasonable people gasping. The good news first—or the bad news, depending on the point of view….

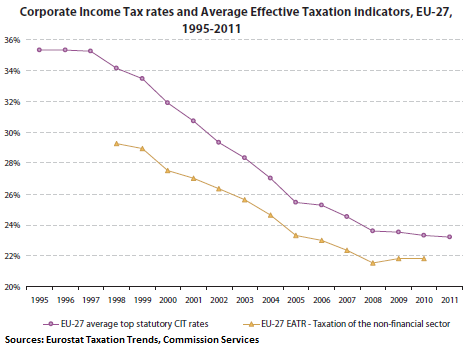

There has been a phenomenal race to the bottom in corporate income taxes across the 27-member European Union, as countries compete to attract businesses. While the debt crisis has slowed this trend, it has not stopped it. The graph below shows the decline of the average top tax rate in the EU, and the parallel decline in the Effective Average Tax Rate (EATR):

For 2012, France is king of the hill with 36.1%, followed by Malta with 35%, and Belgium with 34%. At the bottom are Ireland with 12.5% (it maintained the rate despite heavy pressures from other EU countries to raise it in exchange for bailout payments) and Bulgaria and Cyprus with 10%. How long the race to the bottom can continue is uncertain; people who are experiencing the effects of “austerity” may show some impatience with the corporate sector.

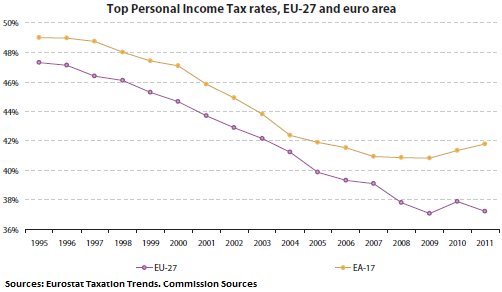

Insidiously, personal income tax rates in the EU, and in particular in the Eurozone (EA-17), have been rising since the beginning of the debt crisis, after many years of declines. In 2010, beleaguered Greece jacked up its top rate by 5 percentage points to 49%, and the UK hit the magic 50%. In 2011, Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Finland raised their personal income tax rates. In 2012, French President François Hollande has vowed to impose a 75% top rate. However, the averages have been kept from skyrocketing by the Eastern Member States that have cut their top rates—Hungary, for example, knocked it from 40% to 16% in 2011.

The greatest personal income tax sinners are Belgium with a top rate of 53.7%, Denmark with 55.4%, and Sweden, congratulations, with 56.6%. Among the heroes: the Czech Republic and Lithuania with 15% and Bulgaria with a lovely 10%.

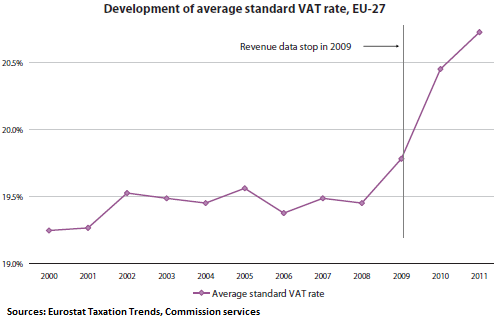

But the shocker in Europe is the Value Added Tax. Unlike a sales tax, a VAT is levied at each stage from production to retail on the difference between input costs and sales price, hence on the “value added.” Countries have large administrations to police this complex system that is rife with fraud. The VAT is applied to services as well—so the base is broad. And the rates are not only confiscatory for most part, but they’re suddenly shooting up:

VAT rates vary from 15% in Luxembourg to 25% in Hungary, Denmark, and Sweden, and a vertigo-inducing 27% in Cyprus—why not make it 100%? Germany is an example of recent trends. The top personal income tax rate dropped from 53.8% in 2000 to 47.5% in 2012, the top corporate income tax rate dropped from 51.6% to 29.8%, and the VAT dropped from 16% to…. Oops! It didn’t drop. It rose to 19%. Thus, people have to pay 18.7% more for the same goods—hitting disproportionately those who spend all the money they make, a good part of the population.

Countries may have lower VAT rates for certain categories. In France, where the standard VAT is 19.6%, the rate for restaurant meals (excluding alcohol) was lowered in 2009 to 5.5%. Other items were already in the 5.5% category, such as cable TV or some pesticides. But restaurants are a significant part of the French economy with €80 billion in sales and 800,000 jobs. As France was getting dragged into the debt crisis, it needed to reduce its budget deficits. Voilà, as of January 1, 2012, the VAT on restaurant meals has been raised to 7%, and President Hollande has threatened to raise it further.

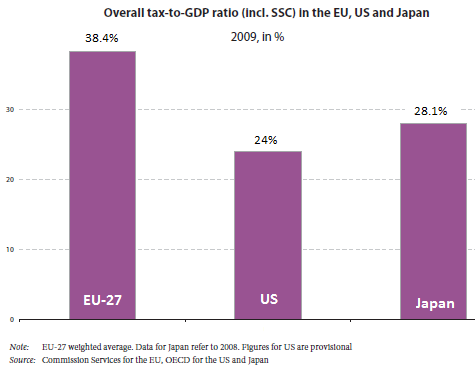

For the EU, tax revenues from all taxes and compulsory social security contributions in 2010 were 38.4% of GDP. On the reasonable end: Lithuania 27.1%, Romania 27.2%, Latvia 27.3%, and Bulgaria 27.4%. At the top: Belgium 43.9%, Sweden 45.8%, and drumroll, Denmark with 47.6% of GDP. Okay, the people may get a lot for it, but by golly, does the government have to confiscate nearly half of the country’s economic output? This is how the EU stacks up against the US and Japan:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()