150 factory workers in China threatened to jump off the roof of an iPhone factory unless they received a raise. Similar stories are accumulating. Inflation, especially in food and other essentials, has been rampant over the last few years—and to make ends meet, desperate workers sometimes take drastic measures. These anecdotes underscore a major trend in China: skyrocketing cost of labor.

In the US, it’s the opposite. Since 2000, real wages (adjusted for inflation) have declined. The White House even touts this horrid statistic in its just released paper, Investing in America: Building an Economy That Lasts. Clearly, the paper is not intended for the rank and file. It outlines how current policies are making America competitive with low-wage countries like China. And one of the principal strategies is … lowering wages:

The paper also touts the administration’s claim of having created 3.2 million jobs over the last 22 months. But these numbers are based on surveys, formulas, and statistical adjustments. The BLS’s Employment Population ratio, which the paper wisely leaves unmentioned, measures the percentage of people age 16 and older who have jobs. It’s the least corruptible employment number available—and at 58.5%, it’s only a fraction above the 58.1% from August, which was the lowest reading since 1983. And it’s far below its peak of 64.7% in April 2000.

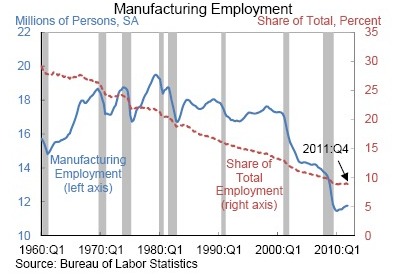

The long decline from 64.7% parallels another statistic mentioned in the paper: from 2001 – 2007, three million manufacturing jobs were lost. Those were the Bush years, obviously. But what happened during the Obama years? Unmentioned, but just as bad.

The tiny hook at the bottom is the ballyhooed uptick. But during the next economic downdraft, the line will likely plunge again. And the slack in employment will continue to contribute to the decline in real wages.

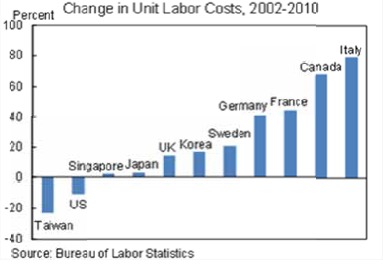

The problem for a high-wage country in a globalized economy is that jobs will be globalized as well. The decision whether or not to offshore production comes down to calculating the total cost of doing business overseas. This includes worker productivity, transportation, supply chain risks, legal and political risks, currency risks, intellectual property risks, expenses for expats, delays, flexibility, environmental issues, taxes, import duties, etc. Hence, for US manufacturing to be competitive, wages don’t need to match Chinese wages, but they need to be closer. That approach in wages has been happening—at a great expense to US workers. And now there are some results.

The paper mentions Ford and Caterpillar as examples of large companies that have announced investments in the US to ‘insource’ jobs from overseas. Those announcements, when they do occur, are made with great political fanfare.

Yet the same companies are still making massive investments in China and other low-wage countries, though no US politician takes credit for that. And there are many others. Merck disclosed from its headquarters in New Jersey that it would build a new facility in Beijing, part of its $1.5 billion investment in China. Nissan, which has large plants in the US, just announced that it would build a plant in Mexico.

So the net of outsourcing and insourcing among large companies still favors outsourcing. But under certain circumstances and on a small scale, companies might try to insource. And that is a step in the right direction.

Smaller companies face different dynamics. It has always been expensive, difficult, and risky for them to offshore production. Many have done it, lured by cheap wages, only to learn costly lessons. And now anecdotal evidence is piling up that they’re having second thoughts. The paper lists KEEN, a footwear maker, and Master Lock as examples of companies that have brought back jobs. I personally know one consumer products company that shut down its manufacturing operations in China and relocated production back to the US (though it still operates plants in other parts of the world). And this is a trend that will likely accelerate.

But low-wage countries will continue to draw jobs away from the US. The numbers couldn’t be clearer: in 2011, the trade deficit with China hit another record north of $320 billion. So taking credit for a wave of ‘insourcing’ from China, as the paper does, has an aura of political grandstanding.

Even the US auto industry, which is relatively cost competitive, isn’t immune from China. Practically every car or truck sold in the US today contains Chinese-made components, though Chinese-designed vehicles haven’t arrived yet. But it’s a priority of the Chinese government. And it’s through the back door.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()