“By restricting capital spending to their highest-return assets and reducing development activity,” oil and gas companies are trying to preserve liquidity, Moody’s explained last week: in aggregate, E&P companies will cut 2015 capital expenditures by 41%. Investment-grade companies, which have not yet lost access to the cheap-money circuit, will reduce CapEx by 36%. But junk-rated companies, which have largely been locked out, will slash CapEx by 47%, Moody’s estimated. And 21% of E&P companies will slash their CapEx by over 60%.

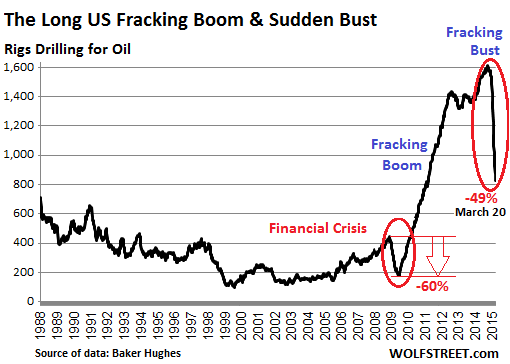

That’s a lot of drilling activity that won’t be happening. But Moody’s was a little late because the slashing, as measured by the number of rigs drilling for oil in the US, has already reached record levels.

In the latest week, drillers idled another 41 oil rigs, according to Baker Hughes. Only 825 rigs were still active, down 48.7% from October. In the 23 weeks since, drillers have idled 784 oil rigs, the steepest, deepest cliff-dive in the history of the data:

The number of rigs drilling for natural gas dropped by 15 to 242, the lowest rig count since March 1992 and down 85% from its peak in 2008.

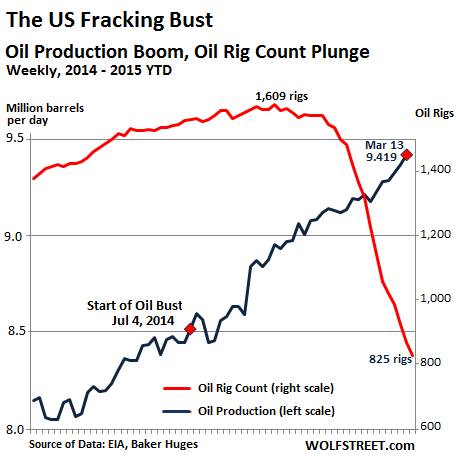

And yet, production is still rising relentlessly.

Natural gas production jumps from record to record. On a weekly basis, it has recently been running about 8% ahead over the same week last year!

Oil production soared by an average of 53,000 barrels per day to 9.419 million barrels per day during the latest reporting week ended March 13, the EIA estimated. The chart, going back to January 2014, compares average daily US crude oil production, as estimated on a weekly basis (blue line, left scale) to the oil rig count (red line, right scale):

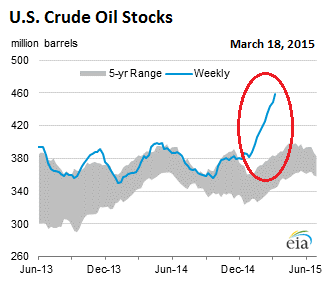

As a consequence of the US oil boom that has been outrunning demand by a wide margin, crude oil inventories have been ballooning. During the latest week, crude oil stocks jumped by 9.6 million barrels to 458.5 million barrels, according to the EIA. To put this into perspective: in seven days, crude oil stocks gained by more than one day’s production! Total stocks are now 22% higher than they were last year, and at the highest level in the data series going back 82 years. This is what that spike looks like:

Rampant speculation is now circulating that the US will run out of crude oil storage capacity, that the critical storage facilities in Cushing, OK, which serves as delivery point for WTI futures contracts, could be full as soon as April. All kinds of numbers are being thrown around to support these assertions.

It reminds me of early 2012, when the same assertions were being propagated about natural gas: storage would be full by the summer or fall that year, and any additionally produced natural gas would have to be flared, that is burned, because there would be no place to put it. And its price would drop to zero.

These assertions caused the price to drop to a decade low in April 2012. But when it became clear that storage facilities could accommodate the natural gas just fine, the price rallied and squeezed the shorts. I expect a similar move in oil. Driving season starts soon. So fasten your seatbelt.

But any rallies will likely have a limited lifespan…. Once again, the same thing that happened in natural gas years ago is now happening in oil. E&P companies have drilled but have not completed or tapped thousands of wells – more than 3,000, according to estimates from Wood Mackenzie and RBC Capital Markets.

“Production” only occurs when oil comes out of the ground. Drillers keep the oil in the ground either as a form of storage to outwait the price collapse or to preserve liquidity by saving the considerable costs of completing the well. That oil adds to pent-up supply. It no longer needs rigs to be produced. The rigs used to drill those wells are reflected in the rig count of the past.

The industry has invented a new term for it, the “fracklog” [Oil Investors, Beware The “Fracklog”]. And it will drag out the oil bust just like the natural gas wells that hadn’t been hooked up to pipelines – but that are now hooked up – are dragging out the natural gas bust. This is serious business, much more serious than the excess in crude oil stocks.

The excess of crude oil stocks is a global phenomenon, and it’s facing a new hiccup. Read… Just as Global Oil Glut Deepens, China Cuts Oil Imports

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

The loss of jobs is not nearly as expected. And for the savers and many other industries (including transport, manufacturing, airlines) I guess the falling price is a good thing.

Hi Wolf – many authors do not distinguish between rigs and wells. Rigs are for exploration and wells are for production – two different categories. I wondered the same while reading your article. Have you properly distinguished these two categories? They stopped exploring but still building new wells in high profitability areas.

Rigs drill wells.

Rig count = how many pieces of equipment (rigs) are busy drilling wells during that week.

Well = hole in the ground.

Production = quantity of oil that comes out the hole in the ground and is sold.

That’s so basic I won’t repeat it in every article.

Wolf – no. I really like reading your website but in this case please do some homework. You imply 1-1 between drilling and producing and it is not even remotely true. They may be drilling many holes before striking resource. The may drill to learn the geometry of the resource and not fro production. There is some correlation between rigs and wells but not very strong one.

Not so basic as you think. And plotting rigs vs. production not very informative. Just look at the charts above…

My best regards.

Maybe this will help:

http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=13551

Clearly you have not read my articles on oil and gas. I have no clue why you think I’m “implying” a 1-1 relationship. Never once said that. But said the opposite constantly.

Yosemite & Wolf,

As long as we are making distinctions, allow me to follow with this. Wells, especially deep wells, say greater than 2,000 feet, for example, are typically drilled with large rotary drilling rigs. Completion and additional post-drilling activities are usually done with smaller, often truck or trailer mounted rigs, generally called work-over rigs. And it is my understanding that in most of the shale plays and some conventional plays, several wells are drilled from one drilling pad, or location. So, after a well, or wells, is drilled, the big rig moves on to the next location, or if there isn’t another location, or job, booked, they may be stacked. The logistics of how wells are drilled and completed may vary from one play to another based on geologic and engineering variabilities.

Rig count is one measure of the relative health of the petroleum industry. And when that count is diving, it ain’t healthy. In the parlance of the industry, wells aren’t built. They are drilled, completed, worked-over and sometimes re-entered. Locations are staked, then built. The completion process is where the initial fracturing, or fracking, occurs, after pipe is run and cemented.

Once the hole is in the ground, a well has been drilled. It may be a dry well (dry hole), a producing well, one which needs further study, or may have future utility and is, therefore, shut-in. Wells may be completed immediately, or kept shut-in awaiting availability of a completion rig, or other equipment or materials, needed to complete the well. A well may be completed and shut-in awaiting a pipeline or gathering system hook up, or may be shut-in awaiting a better economic climate, as Wolf has indicated. Shut-in is both a physical status and a legal term. Legally, as allowed by lease provisions and state and/or Federal regulations, as applicable.

Sorry, but I may have gotten lost in my own head with this reply. I hope I haven’t muddied the water while intending to add some clarity.

Cordially,

Night-train

I think this is helpful Night-train, and it leads to the obvious question : once the rig has finished its work, what is the typical time period, or range of time, that is required to bring production on line?

What you can see here is that even though oil prices started down in July, and the rig decline started three months later (when reality had set in that the price drop wasn’t likely to be transitory) and are now down 50% from October, production continues to rise. It grew about .45 mil in the three months from price peak to rig count peak, and then about the same amount in the five months from rig count peak to current rig count and price bottom(?). What that says is that production growth is slowing. It’s not easy to eyeball this from the charts, and someone should do the actual calculations, but my point is, even if rig count suddenly went to 0 back in October, it wouldnt have made much difference if any in the trend of production in the short-term.

So, my question is, what is the short-term? What is the medium term? If we assumed no rigs, how would production roll off, once the wells that have already been dug are all brought on line, or not brought on line, or shuttered, or ?

We dont really have any numbers on the well uitilization, the various states they can exist in, and what states they do exist in (producing, dry, soon to produce, etc.)

But logically, given what we know of well production rate decline, you have to assume at the historic increasing rate of rigs deployed, that means more wells were coming on line, and there is a fairly smooth curve of those shifting from peak production to declining production. But a fair amount of those that were drilled since the rig count peak, even if they were producing, have not peaked.

Gee,

Good questions. No easy answers. The time from a well reaching total depth (TD), logging the well, releasing the rig, and then moving to the completion phase depends on many factors. Completion rig availability figures in. Service company availability to provide cementing, fracking, ect. has to be considered. If an operator wishes to get a well on-line quickly, the time to begin completion could be a few days to possibly a couple of months, depending of course on operations activity in a given area. The time a well is completed, cleaned up and ready for production, primarily depends on geological and engineering parameters. Again, usually this phase may take a few days to a few weeks. I repeat, many factors are included in the logistics from TD to a producing well. In good times or bad, some of those factors may be beyond the operators control.

I think the point of Wolf’s post is that the operators are intentionally opting to delay completion hoping for higher prices. I believe, particularly, in the shale plays, they are delaying fracking wells, as well, as not beginning production of completed wells. The practice of shutting-in wells capable of production can be a dicey proposition, as sometimes bad things happen to wells as they sit shut-in. By bad things, I mean possible formation deterioration as the well sits idle.

Hope I answered your question, or at least provided more information.

Night-train

There are two major stages to the unconventional ‘tight oil’ extraction process (much like deepwater): stage one is the actual well drilling, the second stage is completion.

Drilling is done to the desired depth and position within the formation then the well is idled. A month or six later, the fracking crews arrive and ‘complete’ the well by removing the temporary casing plugs, installing the fracking stages (perforating the casing- or drill pipe with as many as 36 explosive charges); they then use high pressure pumps and a working fluid to fracture the oil bearing rocks.

Right now there is a backlog of 700+ wells awaiting completion, each represents modest increased output.

Even as drilling slows, the wells already drilled will add to output as they are brought into service.

http://bakken.com/news/id/230208/775-bakken-wells-awaiting-completion/

Because of the very high rate of depletion for tight oil wells, once the completion backlog is cleared total output will decline and do so sharply.

Keep in mind, that the ability of customers to afford oil at any price looks to be shrinking faster than production can be cut (see; China + copper). This dynamic is ‘energy deflation’ and is inevitable, perhaps not at the moment but keep in mind: energy shortages are not a form of ‘efficiency’ and they don’t make anyone richer. There is indeed a marginal glut but overall there is insufficient petroleum energy to meet extrapolated world fuel demand. In other words, if the world was not in a recession, the industry would have to extract upwards of 100 mbpd to meet consumption instead of current 93 mbpd. Likewise, b/c the industry cannot meet the overall consumption requirements, the world economy is wobbling.

Once energy deflation takes hold, a) it will be too late to do anything about it, and b) there will be no escape from the consequences as either any increase- or cut in output will have the same outcome: to put relentless downward pressure on price (and the ability to extract more petroleum).

The only real solution is for moderns to become pro-active and conserve energy … the alternative is stringent energy conservation imposed by events. A good place to start is to get rid of the hundreds of millions of stupid, non-remunerative cars …

http://www.peakprosperity.com/podcast/91722/arthur-berman-why-todays-shale-era-retirement-party-oil-production

The cars are going anyway, like it or not.

Steve from Va.

Good point about the shale plays drilling and completion schedules. Wells are permitted in bulk, drilled and then completed as you stated. It makes sense from a logistical point of view. And should attain an operational efficiency. Same with coalbed methane plays. Way different from drilling them one at a time in in conventional Mid-continent and Gulf Coast plays of my misspent youth.

Night-train

Thanks Steve and Night-Train. That was my basic point. You have to know this lifecycle approach, how many wells have been drilled but not yet brought online, how many are still being drilled (rig count related) and then the decline rates of particular wells, plus, when they will be brought online, if at all. A lot of variables, many unknowns. But the reality is, if you drop rigs, drill fewer holes, somewhere down the line the decline takes over. When? Got me. Most reports I hear are “later this year” but we shall see. I think it could be a bit earlier, given the sharp and continuing drop in rigs, but that as we know is just part of the equation.