“People need to kinda settle in for a while.” That’s what Exxon Mobil CEO Rex Tillerson said about the low price of oil at the company’s investor conference. “I see a lot of supply out there.”

So Exxon is going to do its darnedest to add to this supply: 16 new production projects will start pumping oil and gas through 2017. Production will rise from 4 million barrels per day to 4.3 million. But it will spend less money to get there, largely because suppliers have had to cut their prices.

That’s the global oil story. In the US, a similar scenario is playing out. Drillers are laying some people off, not massive numbers yet. Like Exxon, they’re shoving big price cuts down the throats of their suppliers. They’re cutting back on drilling by idling the least efficient rigs in the least productive plays – and they’re not kidding about that.

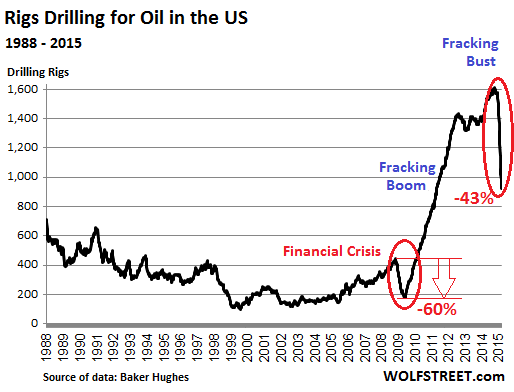

In the latest week, they idled a 64 rigs drilling for oil, according to Baker Hughes, which publishes the data every Friday. Only 922 rigs were still active, down 42.7% from October, when they’d peaked. Within 21 weeks, they’ve taken out 687 rigs, the most terrific, vertigo-inducing oil-rig nose dive in the data series, and possibly in history:

As Exxon and other drillers are overeager to explain: just because we’re cutting capex, and just because the rig count plunges, doesn’t mean our production is going down. And it may not for a long time. Drillers, loaded up with debt, must have the cash flow from production to survive.

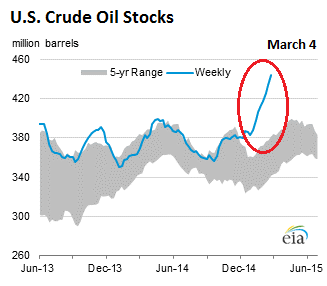

But with demand languishing, US crude oil inventories are building up further. Excluding the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, crude oil stocks rose by another 10.3 million barrels to 444.4 million barrels as of March 4, the highest level in the data series going back to 1982, according to the Energy Information Administration. Crude oil stocks were 22% (80.6 million barrels) higher than at the same time last year.

“When you have that much storage out there, it takes a long time to work that off,” said BP CEO Bob Dudley, possibly with one eye on this chart:

So now there is a lot of discussion when exactly storage facilities will be full, or nearly full, or full in some regions. In theory, once overproduction hits used-up storage capacity, the price of oil will plummet to whatever level short sellers envision in their wildest dreams. Because: what are you going to do with all this oil coming out of the ground with no place to go?

A couple of days ago, the EIA estimated that crude oil stock levels nationwide on February 20 (when they were a lot lower than today) used up 60% of the “working storage capacity,” up from 48% last year at that time. It varied by region:

Capacity is about 67% full in Cushing, Oklahoma (the delivery point for West Texas Intermediate futures contracts), compared with 50% at this point last year. Working capacity in Cushing alone is about 71 million barrels, or … about 14% of the national total.

As of September 2014, storage capacity in the US was 521 million barrels. So if weekly increases amount to an average of 6 million barrels, it would take about 13 weeks to fill the 77 million barrels of remaining capacity. Then all kinds of operational issues would arise. Along with a dizzying plunge in price.

In early 2012, when natural gas hit a decade low of $1.92 per million Btu, they predicted the same: storage would be full, and excess production would have to be flared, that is burned, because there would be no takers, and what else are you going to do with it? So its price would drop to zero.

They actually proffered that, and the media picked it up, and regular folks began shorting natural gas like crazy and got burned themselves, because it didn’t take long for the price to jump 50% and then 100%.

Oil is a different animal. The driving season will start soon. American SUVs and pickups are designed to burn fuel in prodigious quantities. People will be eager to drive them a little more, now that gas is cheaper, and they’ll get busy shortly and fix that inventory problem, at least for this year. But if production continues to rise at this rate, all bets are off for next year.

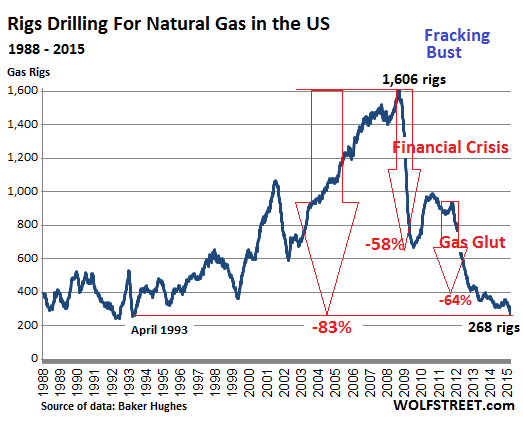

Natural gas, though it refused to go to zero, nevertheless got re-crushed, and the price remains below the cost of production at most wells. Drilling activity has dwindled. Drillers idled 12 gas rigs in the latest week. Now only 268 rigs are drilling for gas, the lowest since April 1993, and down 83.4% from its peak in 2008! This is what the natural gas fracking boom-and-bust cycle looks like:

Yet production has continued to rise. Over the last 12 months, it soared about 9%, which is why the price got re-crushed.

Producing gas at a loss year after year has consequences. For the longest time, drillers were able to paper over their losses on natural gas wells with a variety of means and go back to the big trough and feed on more money that investors were throwing at them, because money is what fracking drills into the ground.

But that trough is no longer being refilled for some companies. And they’re running out. “Restructuring” and “bankruptcy” are suddenly the operative terms. Read… “Default Monday”: Oil & Gas Companies Face Their Creditors

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Wolf – congrats for the excellent articles.

Have you thought of superposing the historic charts for gas rigs and oil rigs? I believe that there is a case to be made that they are one and the same (and when gas prices went down, gas rigs were renamed oil rigs). I think it would make for less fluctuation over the years, even if there would still be a steep decline these past 12 months.

Samurai, indeed. You’re correct about drillers reclassifying their rigs as oil rigs from gas rigs, as I explained in my post on this issues a week ago. And it makes sense, since most fracked wells produce a mix of hydrocarbons, including oil and gas. So they pick whatever looks better to investors. For a while, oil looked better to investors. Now both look bad.

I’m looking at the wells in the Marcellus, which has little oil. All wells have been classified as gas wells. I think over the last year or two, the classification has been reasonable.

Also, fracking at first was used for gas. They had trouble getting the oil out. That’s why fracking for gas started the boom (just after 2000). Once they figured out a few years later how to make it work for oil, fracking for oil took off. And since those wells were a lot more profitable, that’s what they concentrated on.

AND, most importantly, technologies have improved dramatically from those early days. So drilling and fracking a well now takes a fraction of the time it took back then, and once completed, it produces a lot more. So the rig count is only a small part of the story, but it shows the activity going on in the field.

I have my doubts about driving season being able to offset the buildup. We’re also approaching “desperate season” for producers, when the effects of $50 oil truly begin to bite.

They’ll be very desperate for cash soon, more so than before, because it wasn’t supposed to go like this, we were supposed to be well on our way back to $100 oil by now.

Or so most shale producers assumed. Plan B, produce like mad, uncork those wells they thought they could save until oil was higher, whatever it takes to survive another month.

That’s where we’ll be very soon, just in time for driving season.

It should be noted, that some shale producers have hedged their production to 80-90 usd/barrel, and they’re still quite happy keeping their rigs up.

The counterparty isn’t as happy, it would be nice to know who they are and could they go bankcrupt with these horrible deals..

Most companies are hedged but their hedges will end at some point. I have a friend who works for an oil and gas company and their hedges run out next month. He says they had to take a 10% pay cut in January and now they are being told that after the hedges run out, their contracts will not be renewed. Good times are coming indeed.

Hello Wolf.

…” Drillers are laying some people off, not massive numbers yet’…

This Zerohedge article on oil patch layoffs paints a different picture as to the severity of numbers. What would be massive?

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2015-03-06/did-bls-once-again-forget-count-tens-thousands-energy-job-losses

Thank you.

Spencer

Spencer, “massive” in my book would be 100,000+ people laid off in the Houston area alone. Most of the layoffs announced by the big firms were worldwide numbers. So the layoffs in the US were relatively small and spread over a number of states. I know people in OK and TX, and the big layoffs locally have not yet occurred. Everyone is waiting for the next shoe to drop, they told me.

Hadn’t realize just *how* many more rigs were operating in Texas compared to other regions (from Texas Tribune):

http://goo.gl/9Eu4jn

Yes, and when storage is full, and you have to cut price, well, what is the point if everyone is already buying all they need and can’t store more themselves? It’s not like oil has some use on its own. It just sits there. I mean, you could say, hey Gee, I have some near free oil for you. What am I going to do with it? I cant store it. So I can say, hey, how can I create storage cheaply enough to make it worthwhile to buy oil for $5 and store it? But for someone that normally uses oil, this might make sense. But they might also say, wow, oil is super cheap, maybe I should use that instead of some other thing Im substituting. Or perhaps I can find something useful to do with the oil…burn it at burning man?

Anyway, I kid, but at the point when you realize you cant store anymore, partly what happens is you start pushing price down, but at a certain point, you dont actually generate any new demand, or any at all past what you are already selling, and then the logical point is that you finally wake up and cut back on production. Now, who does the cutting is a different issue, but I suspect you could have a leg down before the real production cuts come. But the answer to who folds or is forced to fold makes you think that the fracking rig count has a long way to drop.