“It’s hard to be bullish about the global economy these days” – that’s how National Bank Financial, a division of National Bank of Canada, starts out its report:

Besides China’s tricky rebalancing, which continues to have repercussions across the globe, there’s the growing threat posed by the surging US dollar. The trade-weighted greenback’s over 12% appreciation this year (2015 average versus 2014 average) is the biggest annual appreciation in over 30 years, and that raises the odds of corporate defaults worldwide.

As other currencies have plunged against the dollar, USD-denominated debt owed by corporations, governments, international organizations, and households outside the US gets very expensive or even impossible to service.

Take Petrobras, Brazil’s state-controlled junk-rated oil company with over $130 billion in debt. It’s tangled up in a horrendous corruption scandal and has a host of other problems. Yet last June, it was able to sell 100-year dollar-denominated bonds to investors who clearly weren’t paying attention. Those bonds have since swooned. Much of Petrobras’ production is sold in Brazil at low prices for reis, rather than exported for dollars. And now it has a heck of a time dealing with its mountain of dollar-denominated debt.

It’s not the only one. Something special happened to dollar-denominated debt since the Fed’s QE and ZIRP began, according to a new report by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS):

Since 2008, dollar credit has grown more rapidly outside the United States than inside.

Let that sink in for a moment.

It did so not only because emerging market economies grew faster than the US, but also due “to its substitution for local currency credit, given favorable dollar interest rates and exchange rate expectations as EME firms leveraged up.”

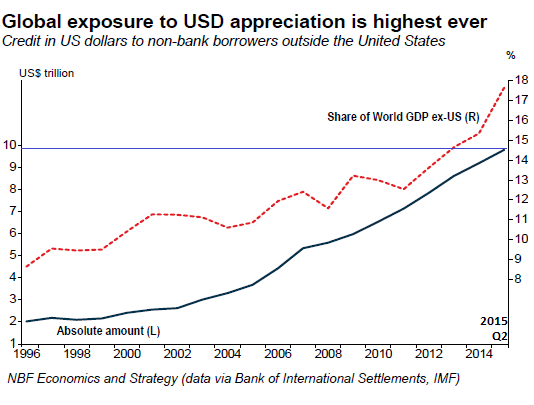

This dollar-denominated debt owed by non-bank borrowers outside the US has grown to $9.8 trillion at the end of the second quarter, up from $9.6 trillion in the first quarter. It has more than quadrupled over the past 20 years. It has nearly doubled since 2008.

In relative terms, it has grown to nearly 18% of global GDP excluding the US, up from 8% just before the Financial Crisis.

Of that $9.8 trillion, borrowers in emerging market economies (EMEs) and their entities residing outside their home countries, such as financing subsidiaries in offshore centers, owed $3.86 trillion.

This chart by National Bank Financial’s Economics and Strategy shows the growth of dollar-denominated debt – loans and bonds – owed by entities in other countries, in dollar amounts (blue line, left scale) and as percent of global GDP excluding the US (red line, right scale):

Of that dollar-denominated debt, bank loans still made up the majority. But the growth since the Financial Crisis has been in bonds. The BIS:

In part, this reflects the retrenchment of global banks, which suffered losses on their cross-border credits during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09 and which have since come under pressure from shareholders and supervisors. But it also reflects the very favorable yields for global borrowers that resulted from the Federal Reserve’s large-scale bond buying.

The composition of this dollar debt varies. Among the top 12 countries, accounting for 75% of this debt, dollar bank loans dominated in China, India, Russia, and Turkey. In the remaining of the top 12, dollar bonds dominate, both corporate and sovereign:

These developments drove a surge in issuance by both long-standing issuers and new ones. Petrobras, among the largest issuers, exemplifies the former. To pay the development costs for offshore oil in the face of cash flows weakened by low domestic administered energy prices … [it] ramped up its dollar debt in 2009-14, with multi-tranche offerings of no less than $8 billion and $6 billion highlighting the ready supply of institutional funds.

Many African sovereigns exemplify the new issuers. Would-be underwriters courted them, mindful that pension funds and mutual funds sought to diversify away from the sovereign debt of the major economies in their portfolios. Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda and Zambia all found ready markets.

At the time of writing, deals are still going through even for non-investment grade sovereign issuers. Ghana, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Zambia all issued in 2015, albeit in smaller amounts or at higher spreads than they desired or had previously achieved. Ethiopia debuted at end-2014, while Angola did so in November 2015.

The report warns that this dollar debt “can leave borrowers vulnerable to rising dollar yields and dollar appreciation” – both of which are already hitting those borrowers hard.

Yet “remarkably little” of this debt is owed to banks or investors in the US. And so the BIS warns: “It is thus understandable that dollar credit to non-US residents has not, until recently, appeared on US radar screens” – despite the risks that it poses to the global economy that in this manner is more than ever exposed to the US dollar, at the worst possible moment.

Already, it’s getting more difficult for these entities to borrow in dollars. Petrobras has trouble accessing the market. Russian borrowers are under sanctions, and collapsed oil prices are crushing their ambitions. The market turbulence this summer in many EMEs didn’t help. So net issuance by these top 12 EMEs has plunged from $41 billion in Q2 to just $5 billion in Q3. In five of the 12, net dollar bond issuance turned negative!

These entities have to deal with their mountain of dollar debt when it matures. When it is no longer possible to issue new debt in dollars at survivable rates to raise the money needed to redeem maturing dollar debt, or worse, when it is no longer possible to even pay the interest, then a classic event takes place: a dollar-denominated debt crisis.

This is when the dollar becomes explosive. Yet another side-effect of the Fed’s ingenious policies that made this possible, and of the market’s blind ambitions to ride these policies all the way to the top without worrying about the inevitable descent.

Steel has become symbolic for what ails China. After years of colossal manufacturing and building booms, ballooning debt, and soaring steel-making capacity, everything has curdled. Read…. China’s Steel Industry Bleeds, Prices Collapse, Losses Mount, and Now the Government Gets Gloomy

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

Here’s the 10 million renmimbi question: who owns that mountain of EME dollar-denominated bonds?

I have the lingering suspicion most of them landed in Europe one way or the other. We are so starved for yield banks barely need to advertise their dollar-denominated bonds and even Turkish lira issues sell in a heartbeat.

With Euribor floating around zero, even bonds issued by Petrobras and Rwanda are scooped up.

Yes, we are that desperate.

Another problem is that the world trade is conducted in dollars, so imports are getting more expensive. While in rich countries that means belt tightening, in poor countries people might spend all their money on food, and iPhones. The last time food prices went up, it ended up in revolts. What will it be this time? Will the barbarians break down the gates of Europe in 2016?

this is one of the more interesting articles i have seen lately, but i don’t know how to take it.

who are the lucky investors in these bonds?

who?

bond funds? sovereigns? chinese banks?

offshore magic buckets?

they can’t be paid back. can’t.

who?

That who question is THE Question.

As when the Em defaults ride in, they will believe me, the IMF will be in the deal, and just like Greece ,the “Private” bond holders, will be taking the biggest, or as we a dealing with full Em’s and Africa, 100% haircuts, whilst the state and bank holders are made whole, or almost so.

Which is why the final solution would simply be to hyperinflate the US Dollar so that every single borrower can pay.

That or World War III with similar end result.

Just like a casino, the house always wins.

It’s good for Americans traveling abroad so that is the one plus. Had a flight to Ecuador in October and had $19/night hotels in Tena, $35/night in Banos and about $75/night in Quito. I was happy with the travel costs. ;-)

Boy, going off the gold standard was SUCH a good idea! Thanks for nothing, Nixon! “We’re all Keynesians now!!”

IMO the problem is even worse than the article states.

Developed/advanced economies are also suffering.

Just look at how much the Australian dollar has fallen over the recent past: from a high of around US$1.10 it fell to around 68 US cents. That is a drop of just under 40%. Now it is around 72 US cents.

No doubt that there are a whole bunch of Australian companies that loaded up on US dollar denominated debt when the Australian dollar was soaring.

(As an aside Australian consumers never saw the benefit of the increase in the A$ in the domestic economy and as a result bought many items over the internet and shipped them to Australia.

For example, I needed a part for my car and the range of prices here in Australia was $110 for a knock off to A$170 from the OEM. Price on eBay was US$22. Add in the ridiculous shipping charge and it was still less than 50% of the knockoff price!)

Gasoline here is still well over US$3.20 a gallon. When we moved here the price was less than half that.)

I wonder how much the fall in the US dollar is going to impact other countries like Canada?

The Japanese Yen, a basket case when looking at the Japanese debt situation, has also fallen like a rock, but that is a different situation as the Japanese hold a huge portfolio of US dollar denominated assets which has appreciated in yen terms.

That is about the only ‘good’ aspect of the fall in the US dollar for them. All those US dollar assets bought when the yen was high is now paying ‘dividends’ and are most likely showing nice capital gains on the books of the banks, insurance companies, and individuals.

AU and NZ dollars have not fallen or weakened very much at all. Compare them to other currency’s outside the US and Eur (which is grossly overvalued).

The period of US dollar weakness has simply come to an end.

The AU $ has not fallen against the NZ $ if the AU $ was truly weak, due to drop in mineral demand, it would do so.

The US dollar is simply recovering from the damage Bush did to it, 08/QE, and the coming end of lame duck O bummer.

In Australia margins fluctuate but prices, do not go down. Freight rates are eye watering, thanks to the bent unions, controlled and milked by the corrupt, like juliar gillard.

Global pricing, drove gas price up, and that is where it will stay, to keep the high-wage indigenous oil industry, profitable.

I like your thinking, hopefully you’re right!

Another facet, Aussie property prices made great gains on the back of surging commodity prices…those who sold at the top are still laughing I wager.

Watch what those prices do in all bands, the foreign buyer premium will finish evaporating. then they will all go sideways, for decades perhaps. Auction clearance rates are almost back to pre Chinese financial invasion percentages, in Sydney premium property.

This is just history repeating, late80’s, in particular.

If by some chance there is a real dip in premium eastern Australian property prices, it will get brought, very quickly. As there is plenty of money in Au/Nz looking for work.

There are no restrictions on Nz citizens buying property in Au. Banks will lend without questions, to 60% of valuation, to people with money.

The only people who will get bitten in this if it gets ugly, are those who over-leveraged at the top of the cycle, mostly buying New development overpriced property’s.