Oil-producing countries dump assets to fill budget holes.

Executive Report with ISA Intel, Oil & Energy Insider:

The collapse in oil prices is draining oil-exporting countries of revenue. With substantially lower oil revenues, many of the world’s sovereign wealth funds are dropping in value, which has ramifications for the assets they are invested in. The IMF took a look at this connection between oil prices and sovereign wealth funds and raised the possibility that asset prices around the world could be negatively impacted.

Oil-Backed Sovereign Wealth Funds

Sovereign wealth funds emerged in a big way when oil prices started to rise in the early 2000s. An enormous transfer of wealth occurred from oil-consuming countries to oil-producing countries. Countries like the U.S., for instance, had to shell out ever more cash to buy imported oil from, say, Saudi Arabia.

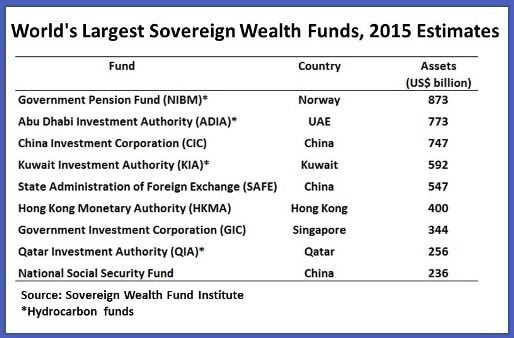

The wealth accumulated in oil-producing countries. Since they needed to put all the surplus somewhere, they setup sovereign wealth funds to invest the money abroad. The IMF says that the total assets from all of the world’s sovereign wealth funds is estimated at $7.3 trillion.

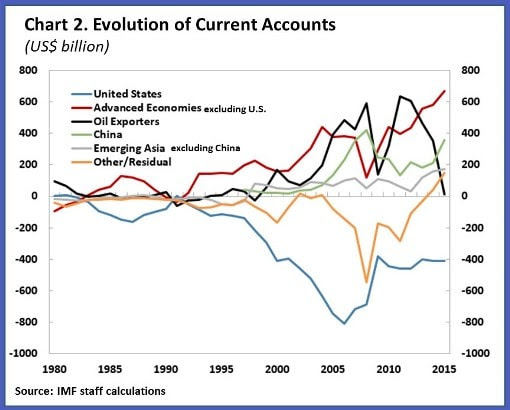

The wealth transfer is clearly visible when looking at the current account balances of several countries. For example, the United States saw its relatively minor current account deficit balloon into a truly massive deficit by 2005, when oil imports peaked and prices rose. Of course, oil-exporting countries saw the mirror image of that experience, with surpluses opening up from 2004/2005 onwards.

The surpluses quickly disappeared following the financial crisis in 2008-2009 – when oil prices crashed below $40 per barrel – but came back relatively quickly following a rapid resurgence in crude prices.

The oil bust that struck last year, however, is something entirely different from the one that occurred in 2009. The collapse in oil prices is not driven by a global economic meltdown; it is a supply-side story. That suggests that the monumental current account surpluses seen in recent years for oil-exporting countries may not come back quickly since there is a low chance of $100 oil again in the near future. The IMF predicts that the combined current account surplus of oil-exporters could rebound to $200 billion by 2020, merely a third of the $630 billion those countries posted in 2011 when oil prices routinely traded above $100 per barrel.

Capital Flows Reverse

So what does all of this mean for sovereign wealth funds and their investments? The world’s largest sovereign wealth funds were made possible by the huge flow of capital into oil-producing countries. The sovereign wealth funds, in turn, reinjected hundreds of billions of dollars into a variety of assets around the world. Notably, a lot of that wealth was plowed into U.S. Treasuries, pushing down interest rates for the U.S., allowing for a large buildup of American consumer debt. Capital also flowed into other assets, such as property, corporate debt, hedge funds, and much more.

Now that the flow has dried up, oil-producing countries are starting to recall some of their investments, pulling out cash that had been parked in an array of assets around the world. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, the world’s largest, just reported a 4.9% loss in the third quarter, the worst quarterly performance in four years.

The IMF estimates that the combined fiscal surplus of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – Oil-exporters from the Arabian Peninsula – will flip into a huge deficit. Before the collapse of oil prices, the IMF predicted that the GCC would post a combined $100 billion fiscal surplus for 2015, plus $200 billion between 2015 and 2020. Now the IMF believes the GCC will have a $145 billion deficit this year, which will widen to $750 billion over the next five years. That equals a net change of $250 billion for 2015 and $950 billion for 2015 to 2020.

Trends to Watch

The sums in question are gargantuan, and depending on how they move, they could ripple across the global economy. Here are a few important trends to watch:

Effects on asset management funds

The obvious and more direct effect could be on individual fund managers who manage investments for the sovereign wealth funds. The FT reports that Saudi Arabia has pulled $70 billion out from external asset managers. “Our view is that if the oil price stays where it is, these [oil-rich] funds will continue to take reserves back,” a Moody’s vice-president told the FT. “Longer term, that’s a trend we view to be negative for the [asset management] sector.”

That is bad news for companies like Blackrock (NYSE: BLK) and State Street (NYSE: STT), large wealth management companies. State Street saw $65 billion in capital outflows from its management in the second quarter of 2015. State Street manages $662 million from the Azerbaijan sovereign wealth fund, but the Azerbaijani fund plans on bringing all of that asset management in-house. Blackrock suffered $24 billion in capital outflows.

JPMorgan (NYSE: JPM), Deutsche Bank (NYSE: DB), and UBS (NYSE: UBS) are also likely to be negatively impacted, but are keeping figures close to the vest. A manager from one of the latter companies conceded that the decision by sovereign wealth funds to pull out cash “hit a little close to home for us,” according to the FT.

“Large asset managers will be hit the most, since sovereign wealth funds tend to prefer well-known brands. They will suffer a double whammy: loss of fees and falling asset values,” concluded Amin Rajan, CEO of Create Research.

Fiscal reforms in oil-producing countries

Capital flowing out from worldwide assets and back to oil-producing countries is occurring because of shrinking revenues. But oil-exporters will also need to undertake fiscal reforms if they want to stop the bleeding. The IMF estimates that a range of oil-producing countries only have a few years’ worth of “fiscal buffers.” At current trends, Saudi Arabia, for example, will run out of cash reserves in five years. Obviously, nobody expects that to happen. But it won’t happen precisely because Saudi Arabia will be forced to make reforms. Saudi oil minister Ali al-Naimi said on October 27 that his country would start slashing domestic fuel subsidies, a hitherto political risk. Fiscally speaking, it is a smart move for the Saudis, but it will also put downward pressure on oil prices if the oil kingdom reduces consumption. In any case, major fiscal reforms will need to be taken in a whole range of oil-exporting countries.

Central bank moves

The capital outflows from sovereign wealth funds could alter the calculations of central banking. The IMF cites a study from the Federal Reserve, which estimates that a decline of capital flows into U.S. Treasuries by $100 billion in a given month could push up interest rates for five-year bonds by 40 to 60 basis points in the short-term. Fewer petrodollars flowing into the United States could push up interest rates.

Obviously, this is a hypothetical, but it highlights the effect of low oil prices: cheap gasoline is a welcome development, but in a roundabout way, the oil bust could also push up the cost of borrowing for the U.S.

To be sure, there are plenty of caveats. Cheap crude, for instance, keeps a lid on inflation, deterring the Fed from raising interest rates, counteracting a withdrawal of capital from sovereign wealth funds.

The effect of capital flows, stemming from low oil prices, is a dynamic question with a lot of moving parts. It is hard to make precise predictions but it is an important trend to watch.

Emerging market assets and currencies

We have already seen a broad selection of emerging market currencies battered over the past year as commodity prices have sunk. If sovereign wealth funds start bringing cash home, that could put further pressure on emerging market assets.

Oil prices

Obviously, a lot depends on oil prices. Sovereign wealth funds would see gains if oil prices rebound. But a rebound is far from assured.

Flows of petrodollars can have dramatic financial, monetary, and fiscal effects. Asset bubbles can occur when oil-producing countries are flush with cash. Skyrocketing property values in London or New York are just one small, but very tangible, effect of rising inflows of capital. Perhaps more consequential is the effect on Treasuries, corporate bonds, currencies, and other asset classes. The flows of capital are rushing back to oil-producers as they take money home, seeking to correct the holes left by low oil prices. The effects of these flows will be enormous. By Executive Report with ISA Intel, Oil & Energy Insider:

Turns out, the oil & gas bust might last a whole lot longer than anyone first thought. Read… Why Investors Should Take “Lower For Longer” Seriously

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()

So, is the premise of this article that US interets rates will rise in conjuction? That would be very amusing…..

see also: “How Quickly Will The Price Of Oil Climb With The Death Of The Petrodollar?” for more data on oil exporting nations.

http://seekingalpha.com/article/3619996-how-quickly-will-the-price-of-oil-climb-with-the-death-of-the-petrodollar

So are rising property prices in New York, San Francisco, London tied to sovereign wealth funds of oil producing countries?

That’s an interesting question. It seems at least London and New York would be good candidates.

surely this is the closest you could reasonably expect to get to being unambiguously good news for oil importers, and equally bad for the exporters? the importers get smaller trade deficits and lower inflation, and how can (no doubt) small increases in interest rates be undesirable when we’ve been stuck in liquidity trap territory ever since the financial crisis? capital inflows into eg London just push up house prices to unaffordable levels while contributing to the UK’s absurdly large current ac deficit – there will be some losers if they disappear, but there will surely be far more winners

Death of the petro dollar??

Not as long as they have the keys to the printing press. There will always be plenty of dollars. What they’ll eventually be worth is the question and here’s the answer:

“Paper money eventually returns to its intrinsic value – zero.” (Voltaire, 1694-1778)