The Fed’s taper “may not be smooth,” explained Charles Bean, Bank of England deputy governor for monetary policy, at the central-banker shindig in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, over the weekend. He was referring to the currencies, bonds, and stocks of emerging-market economies such as Brazil, Indonesia, and India that have gotten massacred.

It started in May when a cacophony of pronouncements from Fed officials of all stripes began to sow doubt about “QE Infinity,” as QE3 had lovingly been dubbed because, unlike its predecessors, it didn’t have an expiration date. Since then, the concept of “infinity” turned into the concept of “taper” and the vague idea that it could end someday.

Interest rates in the US spiked – well, a little, given how much further they have to go. The 10-year Treasury yield jumped from 1.6% in early May to 2.93% last week, though it has since returned to earth, that is to 2.8%. Mortgage rates jumped over a full percentage point. Junk bond yields skyrocketed. Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher mused on Fox: “I think the market has come to realize there’s no QE infinity.”

In an act of central banker irony, the meeting in Jackson Hole was called “Global Dimensions of Unconventional Monetary Policy”; irony because now, five years into the money-printing and bond-buying binge – the “unconventional monetary policy” – they’re thinking about what they have wrought and what the world might come to if they ever stopped the printing binge. They should have held that meeting before they started printing.

Now, five years into it, they’re worried that the mere contemplation of an exit might prick all the gorgeous bubbles they’ve blown around the world and unravel all the intricately woven but otherwise illusory wealth effects.

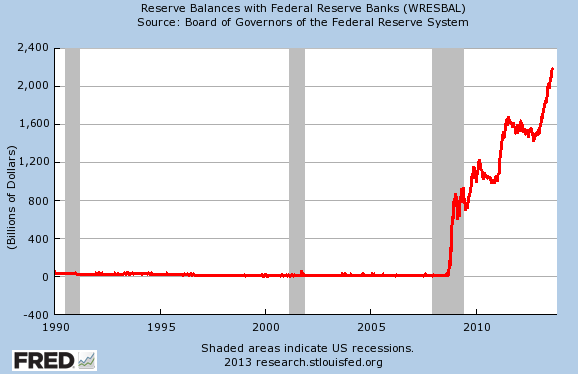

And a binge it was. Reserve balances with Federal Reserve Banks ranged from about $5 billion to $14 billion for much of 2008. But in September, the money-printing operations took off. By the end of the year, the balances reached $847 billion. The printing continued. And each time the Fed tried to stop – at the end of QE1 and at the end of QE2 – financial markets swooned. So the Fed redoubled it efforts to protect its sacred “wealth effect.” By August 21, 2013, the reserve balances had shot up to $2.193 trillion.

The one thing it didn’t do was create a vibrant economy with lots of well-paid fulltime jobs, at least not in the US.

But it did everything else. It created bubbles, market distortions, capital misallocation, and a tsunami of hot money that washed ashore in unexpected places, particularly in emerging markets. But the tsunami is now receding.

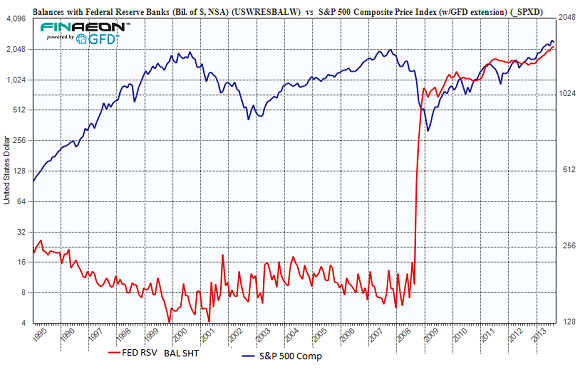

It also fired up a phenomenal stock market rally in the US – despite the lousy economy. The chart below shows the near perfect correlation between the S&P 500 and the amount of money the Fed printed, as measured by the reserve balances on a logarithmic scale – Ralph Dillon of Global Financial Data called it the “drastic correlation between printing and pumping.”

For years, the Fed preached that its money-printing operations would drive up asset values, and they did, and the Fed took credit for it, took credit for the “recovery” of the housing market, took credit for the bubbles in other asset classes, took credit for the “wealth effect” resulting from its “unconventional monetary policy.”

Money printing would cause asset prices to rise, the Fed had said, and when they rose in perfect correlation, there was no doubt about causation. But as the Fed begins to contemplate the end of the binge, Wall Street is suddenly remembering that correlation is not causation.

Just because asset prices soared when the Fed was on a drunken printing binge didn’t mean that they soared because of it. In fact, it has now been determined that they soared independently from the Fed’s actions. And the latest is that higher interest rates will neither prick the reflating housing bubble nor pull the rug out from under the stock market. It’s suddenly some sort of vibrant economy and increasingly invisible corporate revenue growth that will drive stocks ever higher. Alas, bond markets and emerging markets, the first to react when the Fed started printing, have already been bloodied; causation did apparently apply to them.

Banks are already feeling the pain. Refinancing mortgages was phenomenally profitable for them – one of the few growth sectors actually spawned by the Fed’s herculean efforts. Banks went on a hiring binge to shuffle all this paper around and extract fees. But now, with rising rates, that business is getting decimated. Read…. A Very Profitable Part Of Banking Goes Totally To Heck

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()