Normally, the media would have given it priority: French President François Hollande and Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault have become more unpopular than ever before. But the poll was shoved into the background by France’s bombing campaign in Mali—which released an avalanche of positive comments and support from all sides, at least in France. With impeccable timing.

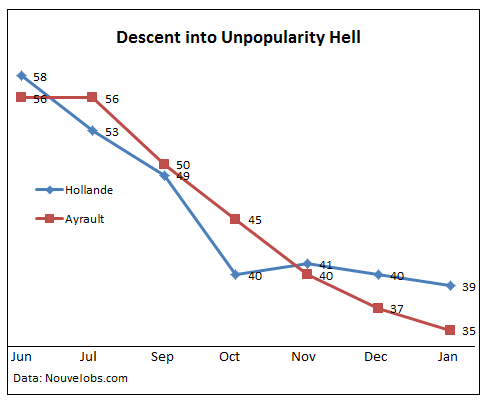

In a poll conducted on Friday and Saturday just before the Mali intervention, only 39% of the respondents had a positive opinion of Hollande, a new low, a plunge of 19 percentage points in seven months. A brief uptick in November had been a mirage. By contrast, Nicolas Sarkozy, during the same period in his term (January 2008), was still riding high with an approval rating of 54%.

And poor Ayrault. He never even had an uptick. His ratings have gone straight to hell. Only the speed has varied from poll to poll. After seven months of watching his handiwork, only 35% of the French still have a positive opinion of him—down 21 percentage points since he took office. His predecessor, François Fillon, had never sunk this low.

“This raises the question of Jean-Marc Ayrault’s legitimacy,” explained the Institute LH2, which had conducted the poll. Even on the left, the “presidential and governmental action is not convincing….” He would soon have to be sacked.

Suddenly the intervention in Mali. It was triggered when jihadists, who’d taken over parts of northern Mali, started rolling south towards Mopti, the second largest city. It has an airport, and a paved highway to Bamako, the capital, about 400 miles to the south. Mopti would have been the staging point for taking Bamako. So the French started bombing jihadist positions and convoys.

It has monopolized French media with talking heads and voices of all stripes, and with a tsunami of articles, overflowing with support for the operations.

Just before 11 p.m. Monday night, Ayrault emerged from a meeting at the Hôtel Matignon, his official residence, where he’d briefed ranking Members of Parliament. Steely-voiced, he told his compatriots: “Faced with the threat of terrorism, the government’s commitment will not weaken. I welcome the support shown by all political forces.”

Every detail was suddenly important. Hollande left for Abu-Dhabi and Dubai, but even while traveling, he’d make decisions. Nigerian troops were on their way to Mali and would be there next week. Algeria, which borders Mali along the northern edge, vowed to close its borders, as did Mali’s other neighbors. According to witnesses, about 30 French armored vehicles entered Mali from the Ivorian border town Pôgô.

Tuareg rebels, who took control of the northern territory of Azawad early last year and declared its independence, only to be sidelined or run off by jihadists, had their own announcement: they offered to support the French. “We’re ready to help, we are already involved in the fight against terrorism,” said a representative of their National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA).

All day, there was similarly exciting stuff to talk about—and the much maligned Prime Minister may have finally found his footing. Even Marine Le Pen, head of the right-wing National Front, who has relentlessly hammered away at the government, and who berated both the Hollande and Sarkozy governments for minimizing the “mounting Islamic fundamentalism in France,” well, even she grudgingly called Hollande’s decision “legitimate.”

There were a few holdouts, however. Jean-Luc Mélenchon, left-wing firebrand and 4th in last year’s presidential elections, grumbled: “The UN mandate stipulated that this was an African problem to be resolved by Africans.” Not known for mincing words, he added, “They’re grown-ups, they have real countries, but yet again we find ourselves going back to our old bad habits of intervening here and there on the continent. We haven’t learned a single lesson.” And he asked, “Which of the wars over the last 20 years that had to be undertaken with urgency, and that would have solved a problem, actually succeeded?”

On the right, Dominique de Villepin, career diplomat, Prime Minister under Jacques Chirac, and archenemy of Sarkozy, penned an editorial that acknowledged the critical situation Mali found itself in when jihadists began rolling south, but… “Let’s not give in to the reflex of war for the sake of war,” he wrote. “The obvious haste, the déjà-vu of the arguments of the ‘war against terrorism’” worried him. “Let’s learn a lesson from a decade of lost wars, in Afghanistan, in Iraq, in Libya.”

Wars, he went on, “promote separatism, failed states, the iron law of armed militias.” He doubted that this war would lead to success; its goals were ill-defined, and France was fighting without a solid Malian partner. Pointing at the coups that had ousted the president in March and the prime minister in December, at the collapse of the divided army, and at the general failure of the state, he asked, “Who will support us?”

But for the moment, these concerns don’t matter. France has found a theme behind which to unite. To heck with the unemployment fiasco, the declining private sector, the collapsing auto industry. A breath of fresh air for the government. To be followed by a major jump in approval ratings. And Ayrault might cling to his job for a while longer.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()