The inexplicable American consumer, the strongest creature out there that no one has been able to subdue yet, has come to grips with a new reality, euphemistically called “New Normal,” though it isn’t normal by any means, but dismal. Feeling more upbeat, they nudged up the Consumer Confidence Index to 73.7, a level not seen since February 2008—a level that caused people to tear their hair out at the time.

Along with other mixed data, it was cited as evidence that things were on an upswing, that the crisis has been brought behind us. But back in February 2008, we fretted about consumer confidence being that low, though it would go on to plunge to levels not thought possible until then.

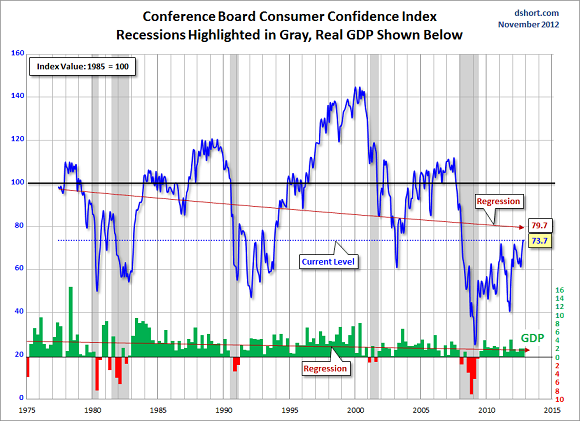

It had been a long way down from the pre-recession level of around 110, and from the halcyon days of the late 1990s through 2001, during the excessively exuberant dotcom bubble, when consumer confidence ranged from 120 to over 140. What on earth were we smoking back then?

This historical perspective casts a pall over the encouraging tone that oozed from the Confidence Board’s press release: “Over the past few months, consumers have grown increasingly more upbeat about the current and expected state of the job market, and this turnaround in sentiment is helping to boost confidence.”

During each of the five recessions since the Board’s data series started in 1977, consumer confidence took a dramatic nosedive. But following the dotcom-bubble peak of over 140, where oxygen was thin, consumer confidence crashed over 80 points, more than ever before, reflecting the crash of stock portfolios that were supposed to lead to very early retirement and decades of watching one’s millions beget more millions on an annual basis. It punched consumers in the gut; confidence collapsed.

Then the Fed dumped cheap money on the land to create another asset bubble, in housing this time, which nurtured consumer confidence back to life—above the magic line of 100, the level of 1985—to peak at 110. When that bubble blew up as well, consumers gave up trying to be artificially confident.

The index dropped to a record low, so low that today’s awful number looks pretty good in comparison. That history of lower lows and lower highs since the peak of 2001 has been captured by one of Doug Short‘s excellent graphs:

The confidence peak of 2001 coincided roughly with the real wage peak (wages adjusted for inflation). Since then, nominal wages have continued to rise in their hopscotch manner, but have risen less than the rate of inflation. And now, for most workers (except for the upper echelon), real wages are significantly lower than they’d been a decade ago.

During 2011 and 2012, real wages continued their tailspin. Only July this year, when inflation was exceptionally low, were they flat. But now, real wage declines are steepening again. The numbers may vary, depending on who is counting and what inflation measure is being applied. But the trend isn’t going to slow down: Fed governors have been crisscrossing the country, explaining to us nonbelievers that the US needs more inflation, not less. Hence, even lower real wages.

Anecdotal evidence sheds additional light on how people react to it. We all know people who lost their jobs during the Great Recession and have now found jobs—but at lower compensation levels than before. I know a few who got to keep their jobs, but were handed hefty pay cuts in 2009. And both groups have gotten used to their lower incomes and have adjusted. They have come to grips with their own new reality. Their confidence, smashed during the crisis, has been edging up again as well. Time heals many wounds.

But it won’t make up for pay cuts and inflation. Only borrowing can do that. And so, as confidence is creeping up from the horrid levels at the trough of the Great Recession to the merely dismal levels of today, the inexplicable American consumer—who is becoming more explicable by the minute—may pull out a wad of credit cards to fund serial spending sprees. The shopping season, as the holiday season should be called, may document that move. But if consumers think of their lower real incomes and remember to be prudent with their credit cards, we might have to fasten our seatbelts early next year.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()