The plight of natural gas driller Chesapeake Energy could almost make you feel sorry for the board of directors and CEO Aubrey McClendon. He lost his chairmanship after his conflicted entanglements and an in-house hedge fund seeped to the surface. The company announced it may run out of cash to fund its drilling operations next year. Fitch, in downgrading Chesapeake’s Issuer Default Rating and senior unsecured ratings to BB-, estimated that the shortfall this year alone would reach $10 billion—in the first quarter, the company bled $3 billion in cash—and that it would be forced to dump up to $20 billion in assets to get through this.

But Chesapeake’s ability to get new money should not be underestimated during these crazy times when the Fed keeps iron-fisted control of the credit markets with its zero interest rate policy. Investors are dying for yield, at any risk. So Chesapeake got a loan of $4 billion from Goldman Sachs and Jefferies Group to bridge the current hole until some asset sales come through, hopefully. And all due to the low price of natural gas and the ugly economics of fracking.

Fracking, which allows drillers to get gas and oil from shale deep underground, triggered a revolution. Gas production in the US has been setting new highs, and as supply overwhelmed demand, prices have collapsed. Gas in storage is at a record high for this time of the year, and some doom-and-gloom prophets maintain that storage will reach capacity this fall, and that producers won’t be able to get rid of their gas and will have to flare it, pushing its price to zero.

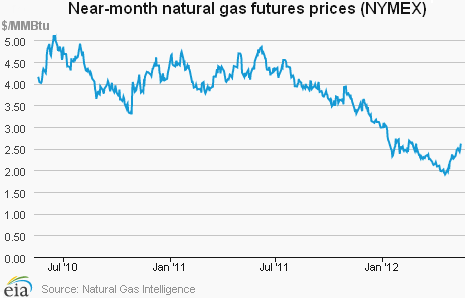

However, natural gas for June delivery settled on Wednesday at $2.73 per million Btu on the New York Mercantile Exchange. A 44% jump from its April 19 low of $1.90 per million Btu, but still only half the five year average, and below the already low price at the beginning of the year. As this chart shows, the recent uptick isn’t much of a salvation for the beleaguered drillers.

In fracking, during the initial phase of production, high pressure blows a huge quantity of gas out the well—and the quantity of the first 24 hours, the “initial production,” is bandied about to investors and lenders, who are so impressed.

Alas, it’s the most the well will ever produce in a 24-hour period. As pressure drops, gas production drops precipitously. All wells have decline rates. But instead of declining gradually over decades, shale gas wells decline sharply over days, weeks, and months. After a year, production may be down by 80%, and after a year and a half by 90%. But the outsized production early in the lifecycle allows drillers to show a big upfront profit. To conceal the decline rates, they drill another well. And another well, and so on. The more they drill, the more they have to drill to hide the drop-off in production of the prior wells—ad infinitum! Which is impossible. But drillers kept it up long enough to get prices to collapse. And then, what caught up with them was … reality.

The industry even has a term for it: Ultimate Economic Recovery (UER), the quantity of gas a well produces over its life. Since no shale gas wells have lived through the entire lifecycle yet, UER numbers have to be estimated, and they now appear to be much lower than the initial industry estimates that were mostly hype. Whether or not a well is profitable over its life depends on the UER, the cost of drilling and maintaining the well, and the price of gas during that time. An excellent pricing model for the Barnett Shale field determined that a well might become profitable over its life if gas is at $8 per million Btu.

Even if the model is off a bit, it shows that the industry has been fracking at a steep loss for years. But due to the way gas drillers account for their wells by front-loading profits, the pain has mostly shown up in their ballooning debt and their current negative operating cash flows. Hence, Chesapeake’s dire situation. Drillers have shifted whenever possible from drilling for natural gas to drilling for oil, which is still highly profitable. And so, the rig count for gas wells has been heading south, from over 900 last fall to 600 last week (Baker Hughes).

Turns out, the shale gas revolution is an uneconomic activity even at much higher prices and is sustainable only for a limited time and only by blowing through loads of borrowed money. Now debt has piled up, cash flow is negative, and solvency risks are gathering on the horizon.

With money running out to drill new wells, the steep production declines inherent in all shale gas wells are oozing into P&L statements, and suddenly, all that debt that made so much sense a year or two ago is unmanageable. Assets have to be sold off in a hurry, drilling diminishes further, and a vicious cycle overtakes the false promises of yore. And production, which lags behind rig count movements, will drop, and drop steeply.

Meanwhile, the low price of gas has bent the demand curve: utilities are shifting massively from coal to gas for power generation. Their demand is eating through the record amount in storage and will clash later this year with diminishing production. It’s a classic example of how a price that is too low will spike, but only after a monumental massacre in the industry. Read…. Havoc and Opportunity in Natural Gas.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()