A new report from Natixis, the asset management and investment banking division of Groupe BPCE, the second largest bank in France and one of the largest megabanks in the world with over $1.4 trillion in assets, predicts what daredevil voices at the maligned margin of financial analysis have worried about for a while: the likelihood another financial panic.

It will be caused ironically by the very mechanisms that are still used to “fix” the last financial crisis: money-printing and asset-purchases by major central banks around the world that unleashed a global flood of liquidity, month after month, for over five years.

Most of this practically unimaginable mountain of moolah that has landed in the laps of banks, institutional investors, hedge funds, private equity firms, and other speculators has not been used to boost lending to the private sector in OECD countries, the report confirmed, and thus has not contributed to the recovery of the real economy in those countries. Instead, it has been poured into financial assets and has artificially goosed their valuations.

This money sloshing through the system and the persistence of zero-interest-rate policies have driven desperate investors ever further out into “all risky asset classes,” including emerging assets, junk-rated corporate credit, Eurozone peripheral debt, and equities. That buying pressure has inflated their valuations even further. And in the emerging markets, it led to an appreciation of exchange rates.

After the May 2013 revelation that the Fed was thinking about tapering its asset purchases, previously considered QE Infinity, there was a whiff of panic. Capital began to flee emerging economies, and their asset prices and exchange rates swooned. But now, the hot money is pouring back into emerging assets, once again inflating valuations and exchange rates.

Investors are holding their noses and closing their eyes, and they’re buying even the crappiest debt of peripheral Eurozone countries, motivated by the ECB’s 2012 pledge to do “whatever it takes” to keep the Eurozone together. So an international feeding frenzy broke out over the bonds that the Greek government sold last week, only a couple of years after prior bondholders had been treated to a terrible haircut. Valuations were so excessive that the paper, larded with risks and supported by an economy in shambles, yielded less than an FDIC insured one-year CD did before the crisis.

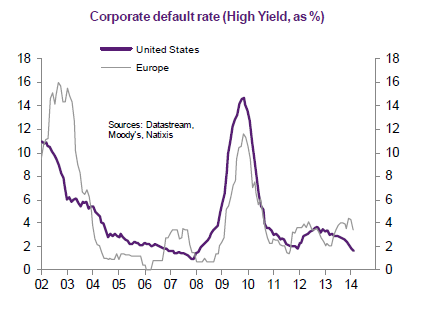

At the same time, starting in 2012, “we saw large buying flows of corporate bonds.” Credit spreads tightened and risk premiums evaporated. With unlimited new and nearly free money available to junk-rated companies that would otherwise have trouble servicing their debt, default rates have been low. But default rates explode when the tide turns, as it did during the financial crisis, and this is going to happen again:

And investors have been plowing money into equities and whipping many indices around the world from one high to the next, “despite the geopolitical risks and the uncertainties lingering over growth.”

This is exactly what the Fed and other central banks have explicitly wanted to achieve with their staggered and well-coordinated waves of QE. They’ve separated markets from reality. They’ve eliminated gravity. They’ve created that infamous wealth effect. As a result, “investors are ignoring the risks weighing on the different asset classes”:

- External deficits and “virtual stagnation” of industrial production in the large emerging countries

- Credit spreads that no longer cover the average risk of corporate default over the maturity of a bond

- Still rising public debt ratios in the peripheral Eurozone countries

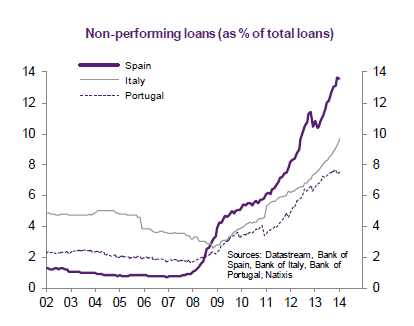

- Soaring non-performing loans at banks in peripheral Eurozone countries; a horror picture belying any official protestations of a banking recovery:

And then the report added gingerly, not wanting to be held responsible for having created a stock-market panic on its own: “If share prices continue to rise, the valuation of equities will become abnormally high in relation to past levels….”

“We can see where this is heading,” the report said. Namely toward a situation where the prevailing “abundance of liquidity” and near-zero returns on risk-free assets are driving investors into emerging assets, corporate credit, Eurozone peripherals, and equities. And then “all risky asset classes will become overvalued.”

And what are investors going to do, once they open their eyes and figure this out?

The report by the second largest megabank in France, one of the largest in the world, the epitome of mainstream finance, comes to the same conclusion that those intrepid but maligned voices on the margin of financial analysis have offered for a while: “There are grounds to fear an episode of widespread panic among investors,” who would try to dump all risky assets at the same time, with buyers running for the exits too, “as we saw in 2008 and 2009.”

Fasten your seatbelts, they’re saying.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the mug to find out how:

![]()